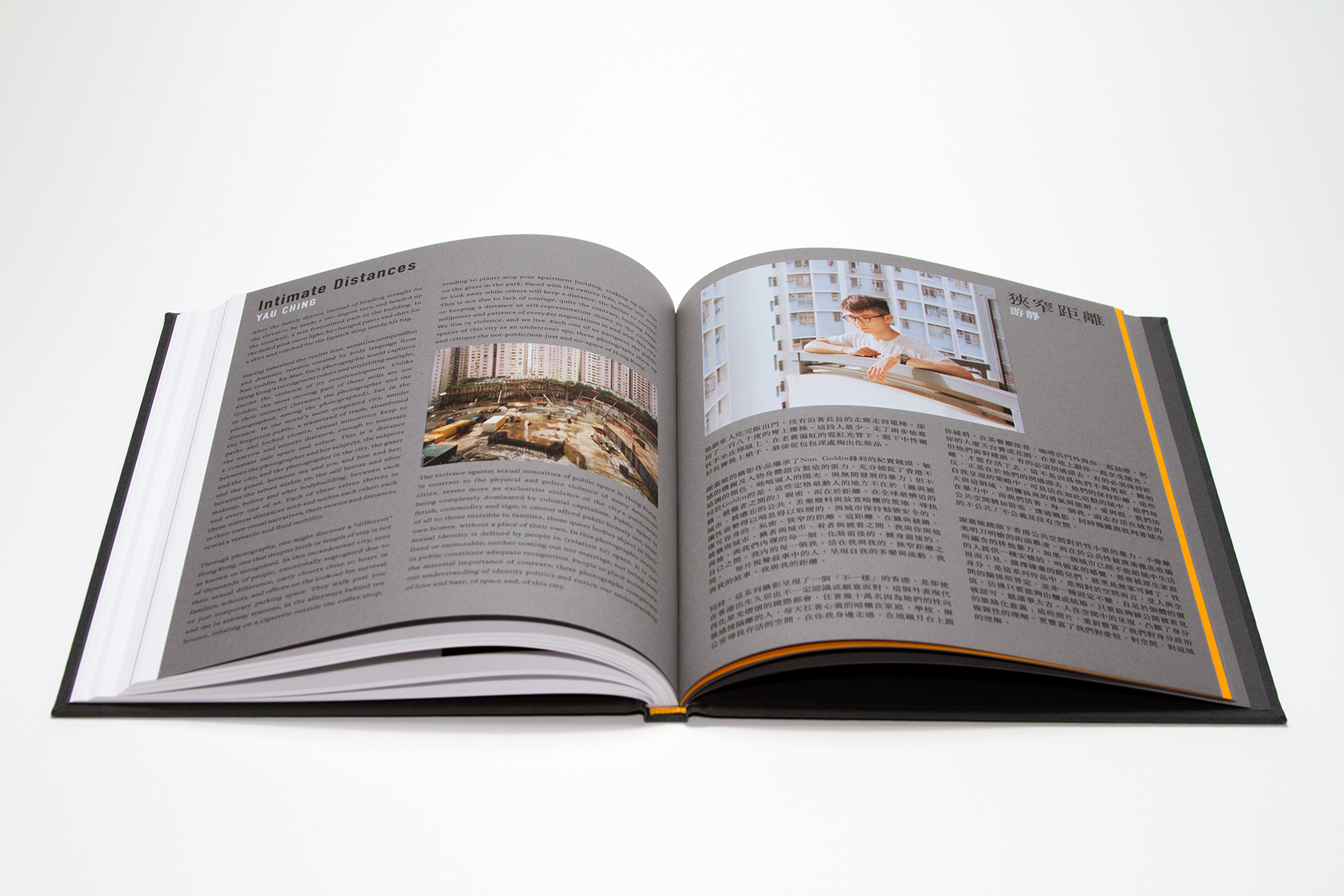

Book Review: Ka-man tse’s “Narrow Distances”

By Jess T. Dugan | December 12, 2018

Published by Candor Arts in 2018

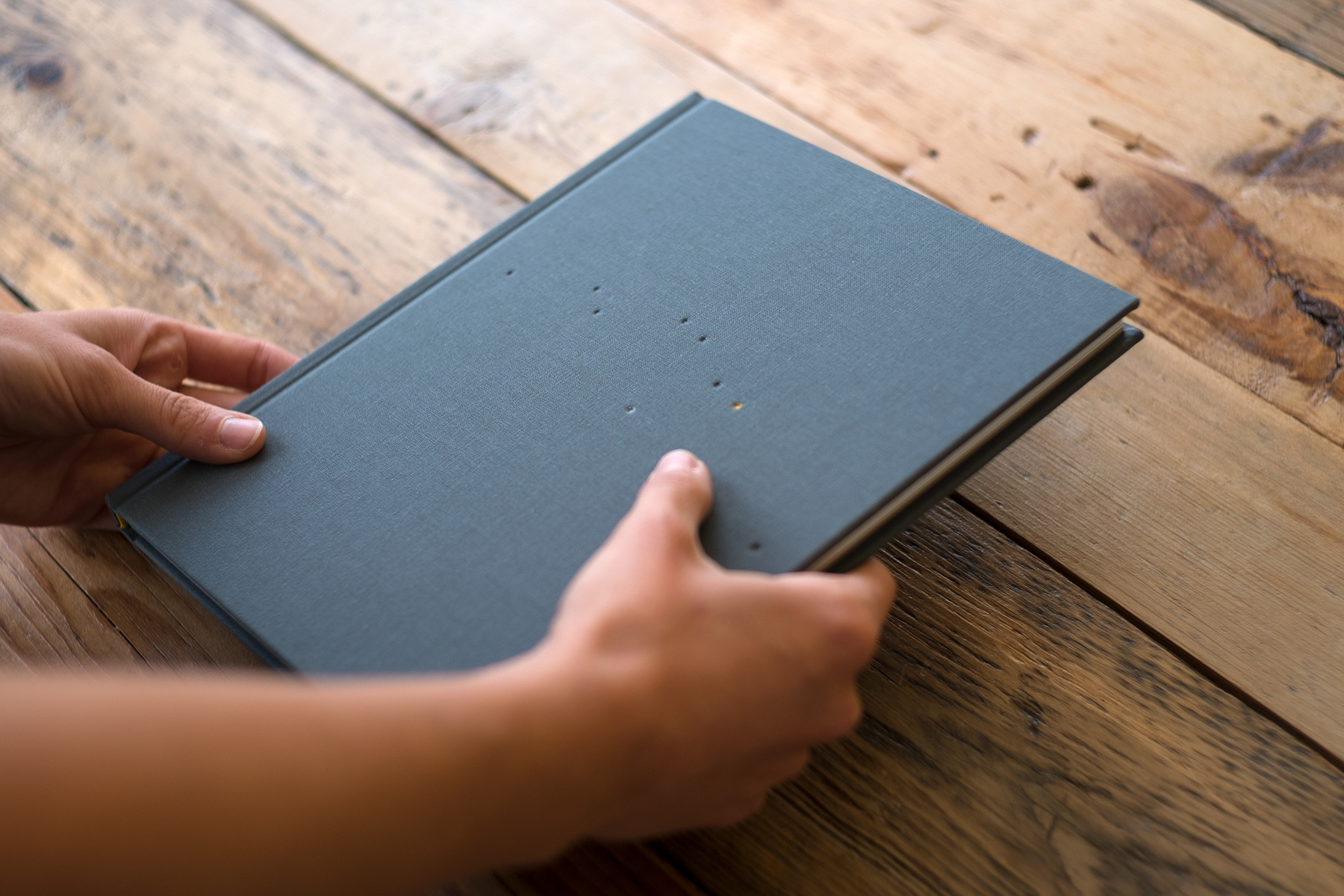

8.5" x 10" x .6875", 136 pages / First Edition 400 copies

Smythe-sewn clothbound hardcover / Foil stamped and debossed cover and spine

Design by Matt Austin / Sequencing by Ka-Man Tse, Matt Austin, and Melanie Bohrer / Foil stamping and casebinding by Candor Arts

Ka-Man Tse’s book, narrow distances, published in 2018 by Candor Arts, is a collection of photographs that explore identity, sexuality, community, shared space, and connection in contemporary Hong Kong. Tse was born in Kowloon, Hong Kong and emigrated to the United States with her family as an infant. Her mother’s family lives in Hong Kong and most of her father’s family has emigrated to the United States; Tse returns to Hong Kong twice a year.

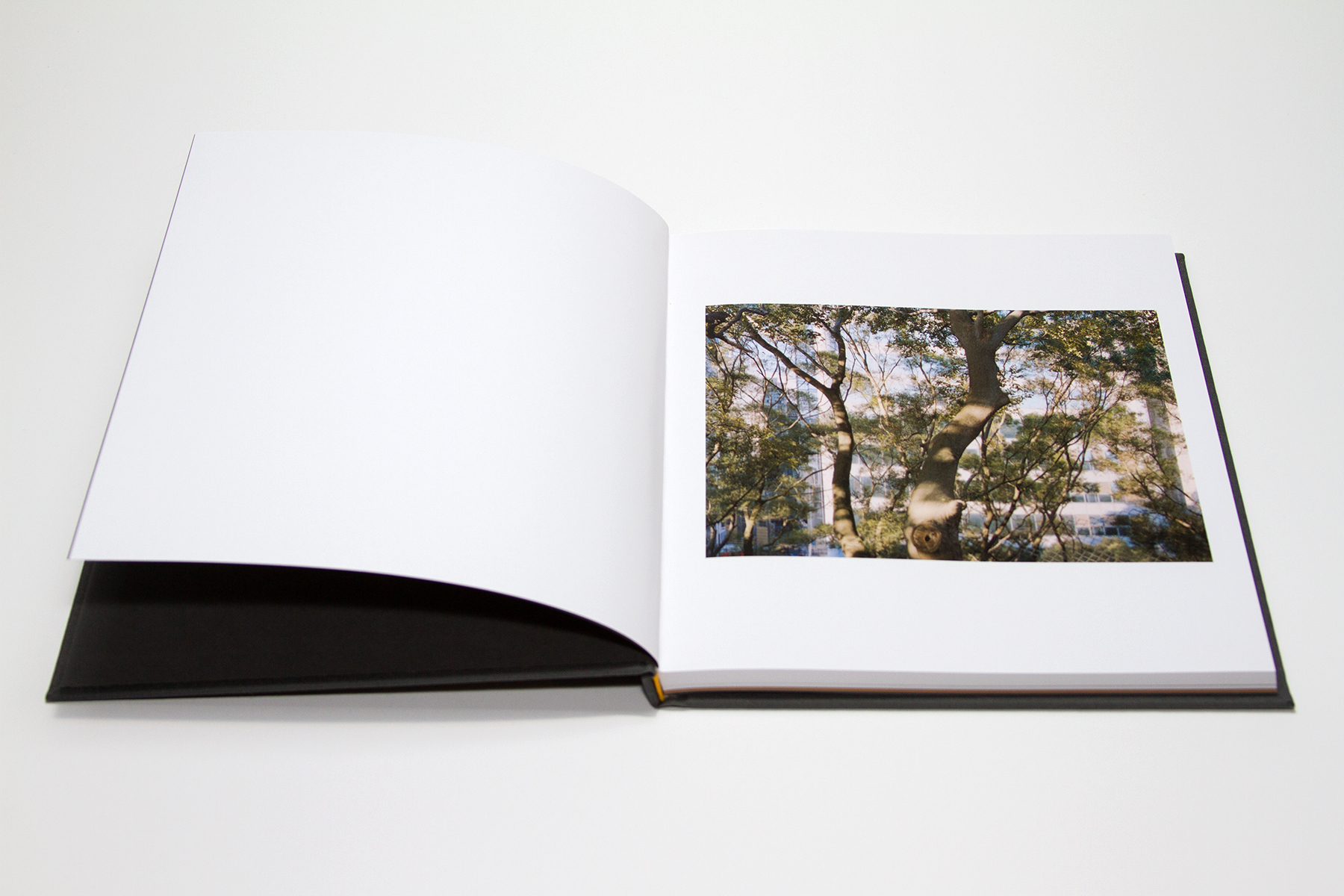

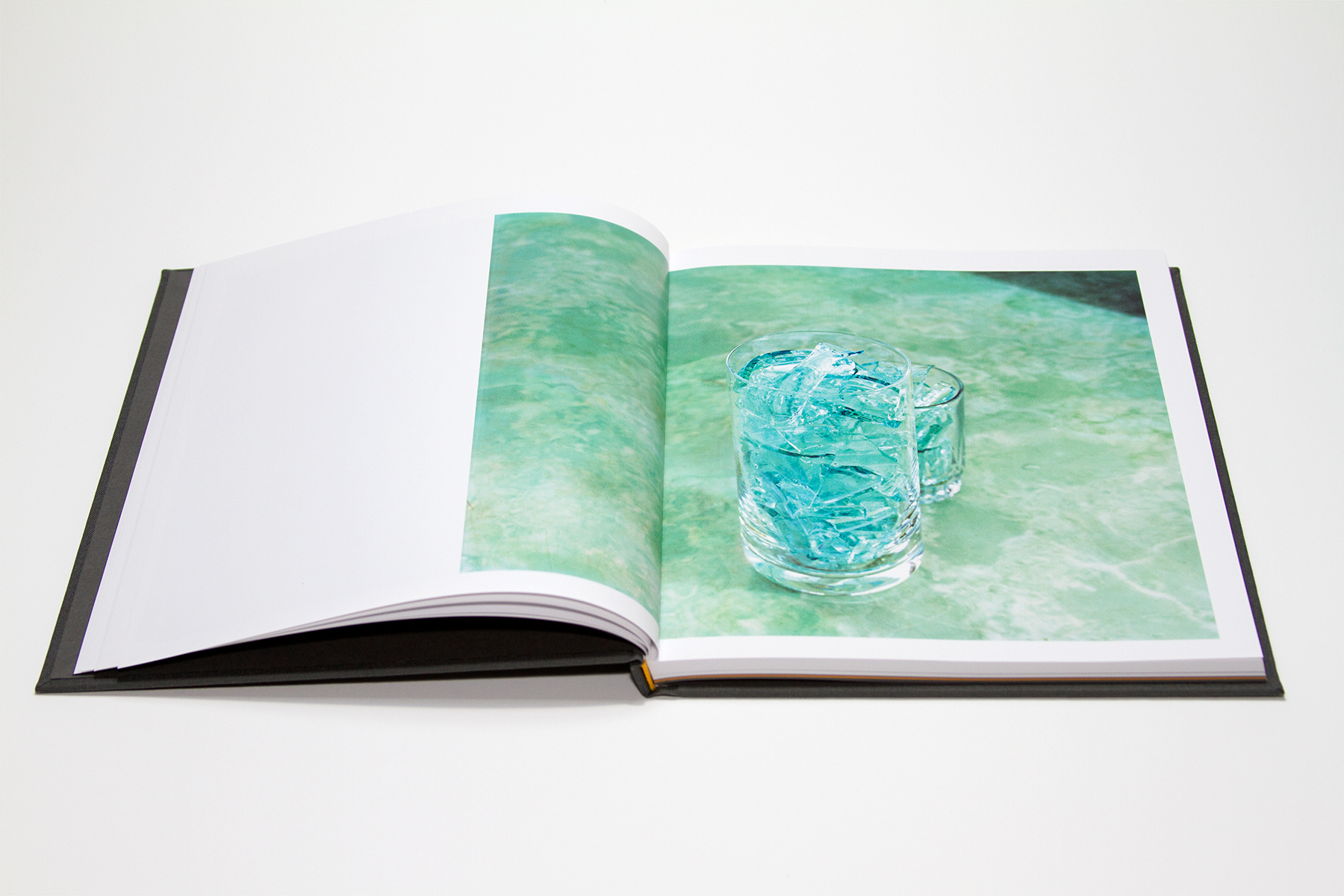

The book opens with an image of a building obscured by a thick maze of trees, which immediately sets the stage for the images that will follow: a depiction of life and vitality against a large, dense, urban background. The idea of constant change, both personal and social, is consistently present throughout the book. Tse introduces us to a world of intense physical overdevelopment, where personal space is a luxury, and where finding space – both literally and emotionally – for queerness is difficult. Narrow distances is about this negotiation of physical space as much as it is about personal experience. In her essay towards the end of the book, Intimate Distances, Yau Ching writes:

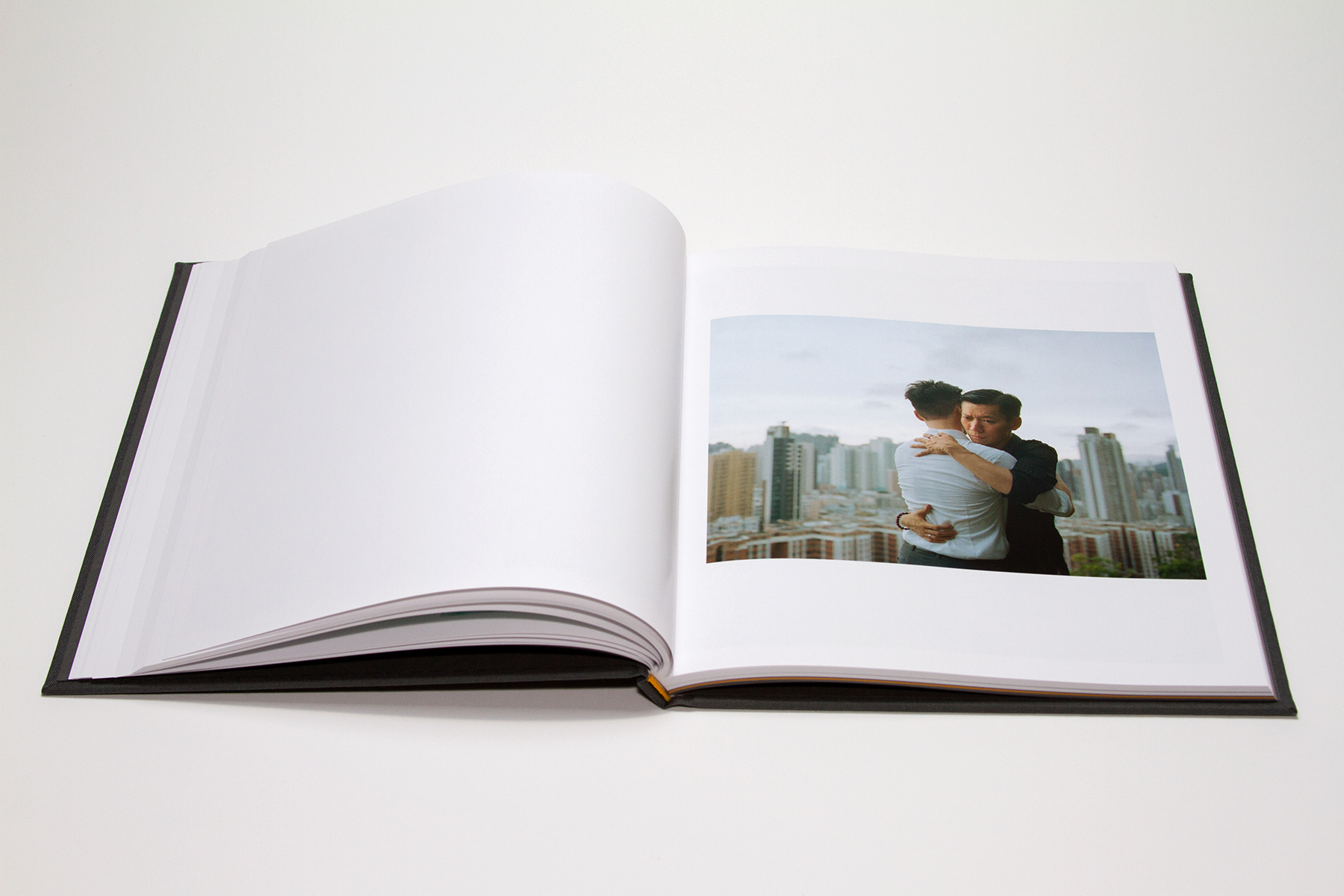

The most moving part of these stills are not in their intimacy (between the photographer and the photographed, among the photographed), but in the distance. In the world’s most congested city, amidst the forgotten public, a wasteland of trash, abandoned paths and locked closets, sexual minorities keep to the narrow and minute distance, enough to maintain a constant safe space and solace. This is a distance between the photographer and her subjects, the subjects and the city, and the photographer in the city, the gazer and the gazed, between me and you and him and her, between the selves within us, the self before and after makeup, before and after bodybuilding, between each and every one of us. Each of these selves thrives in these narrow distances with and within each other; each in their own visual narratives, their stories and distances reveal a versatile and fluid mobility.

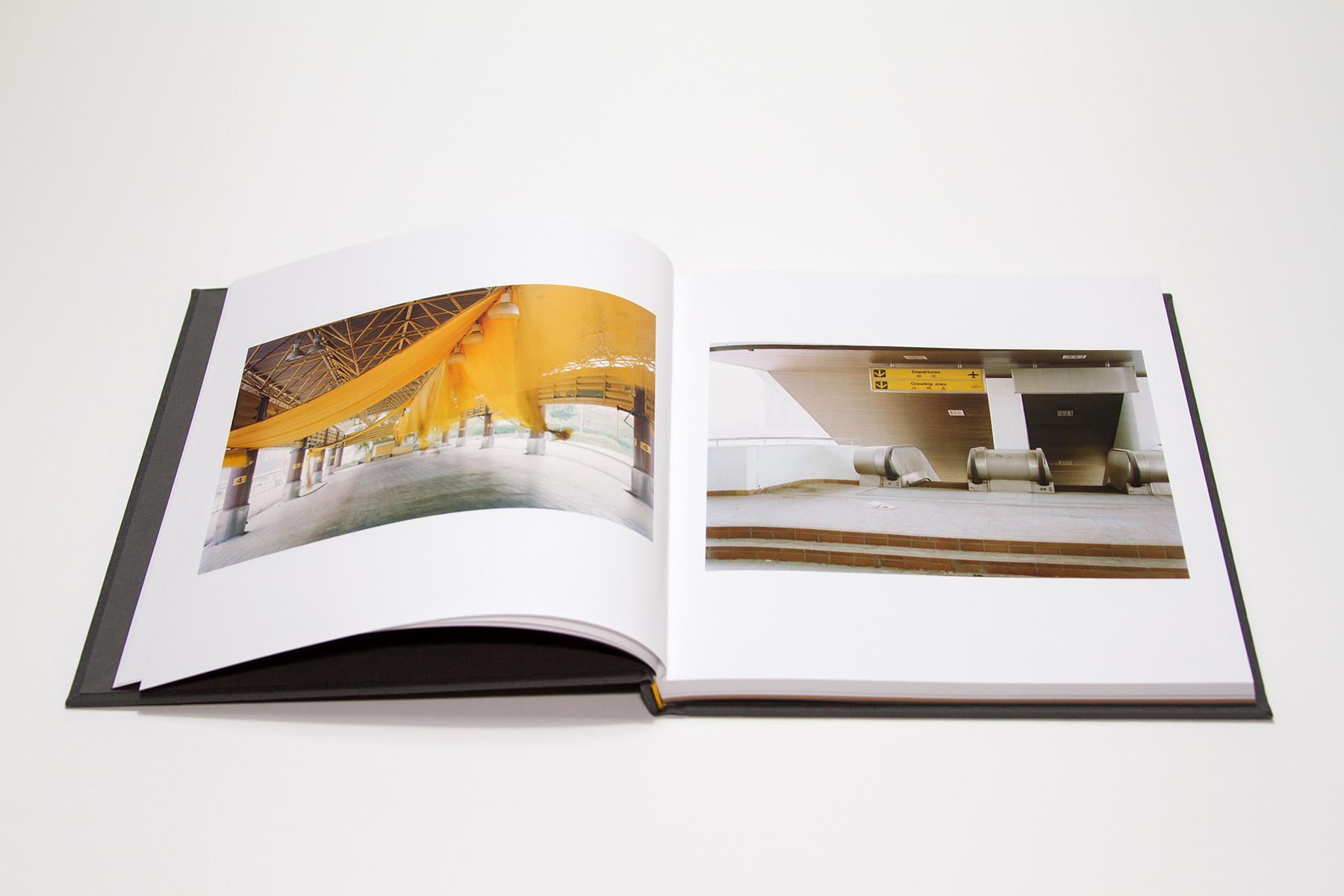

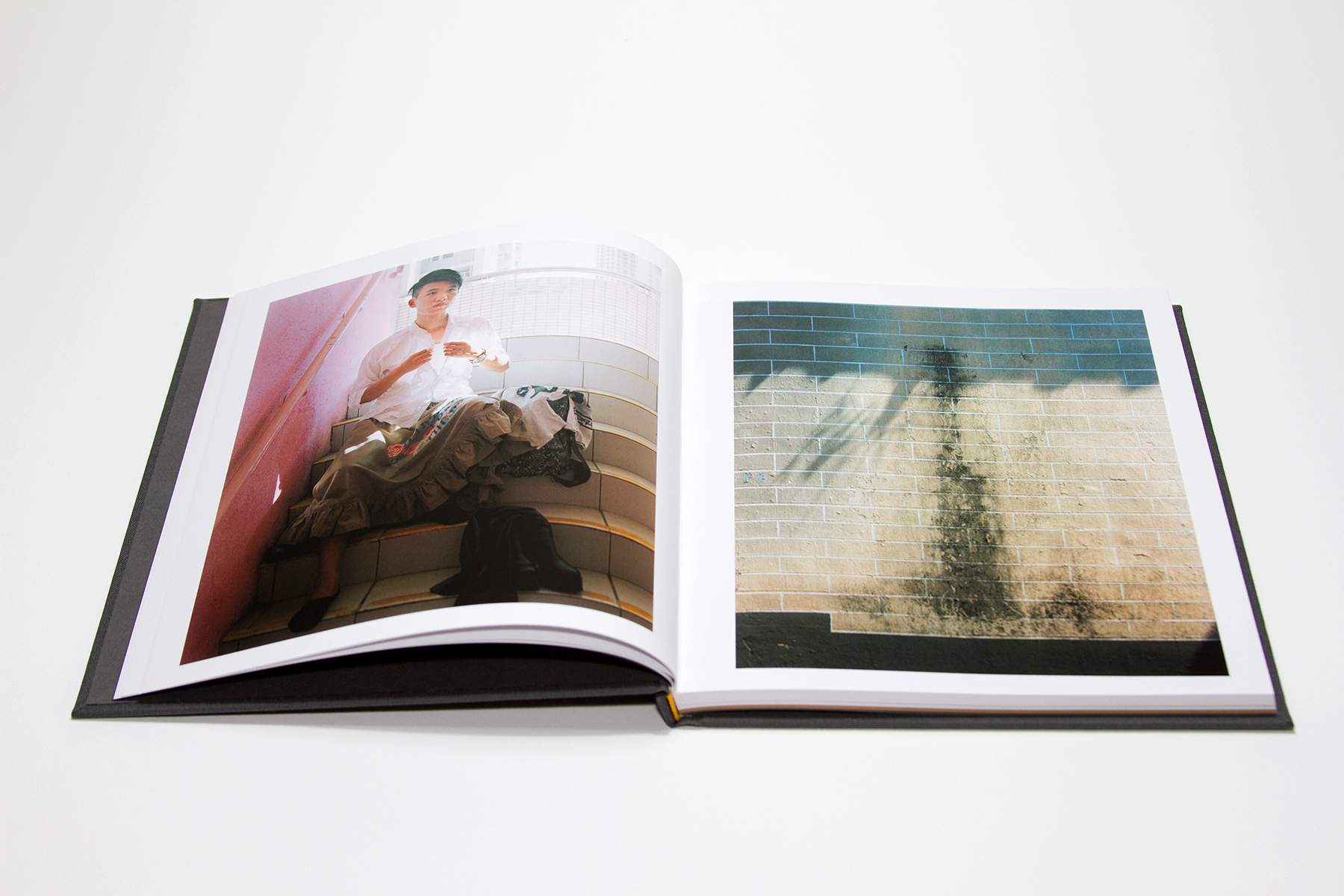

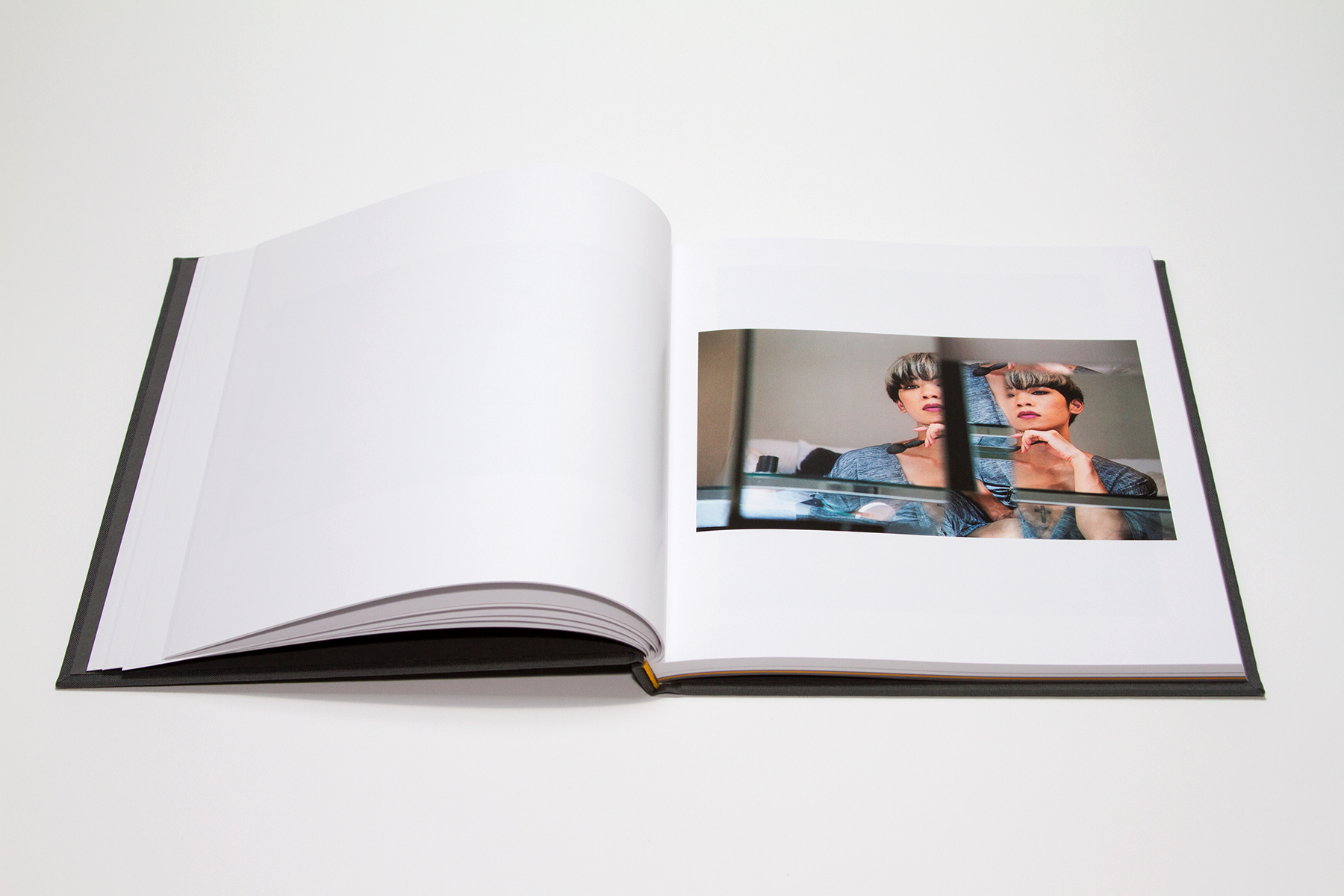

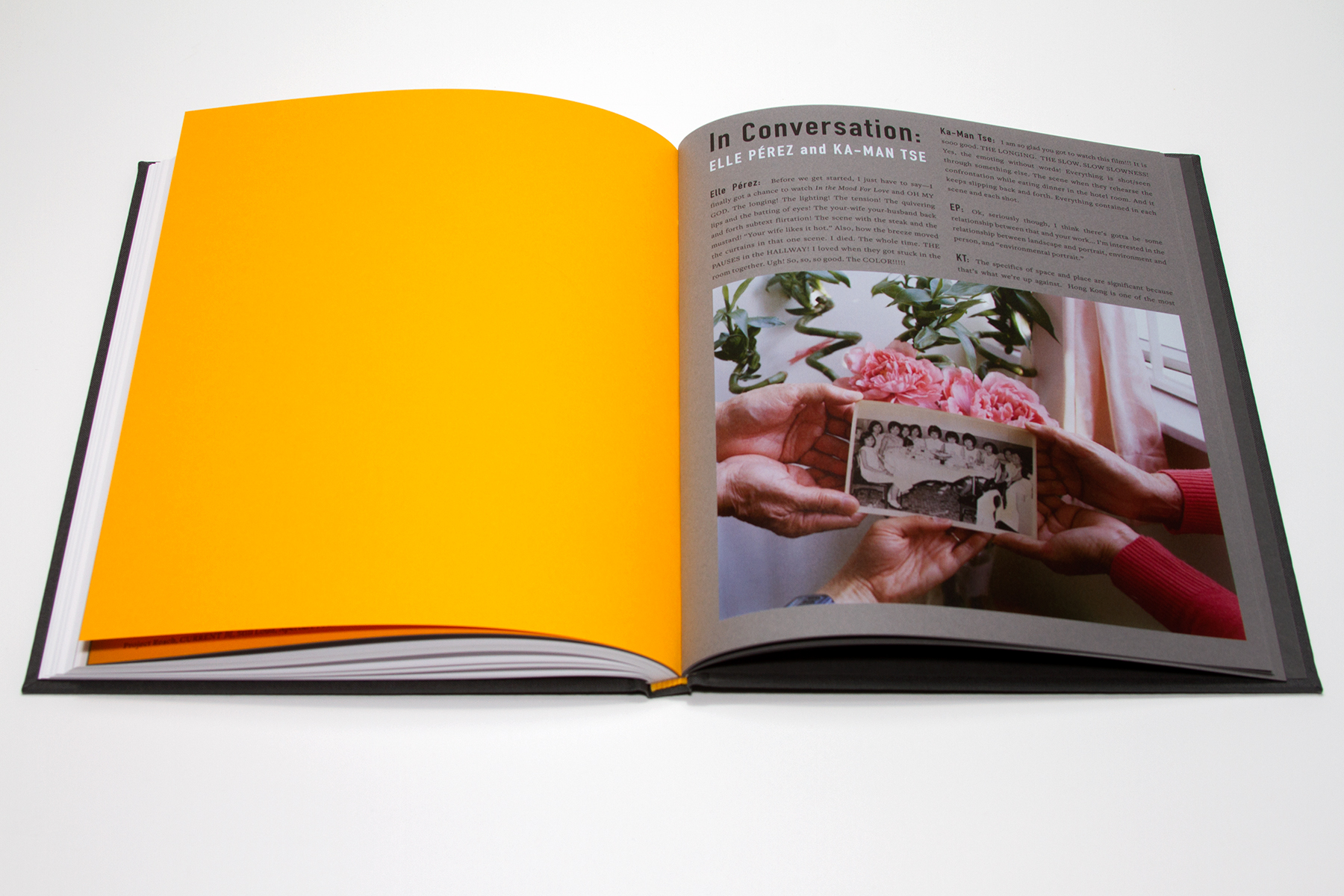

Tse works with a 4 x 5 view camera, a slow process that requires collaboration between photographer and subject. She writes that this slowing down “feels counterintuitive in such a city,” but ultimately is a radical process of connection. In her photographs, small gestures become magnified: the holding of hands, the sharing of a cigarette, lying together on a blanket in public, putting on makeup, hugging, sharing a meal, laying together on a rooftop or by the water. Each of these activities takes on a heightened significance, imbued with urgency, desire, and defiance of prevailing social and cultural norms. Tse includes overt signs of queerness in her photographs, yet she is clear that this project is not only about visibility. Rather than simply asserting the existence of queerness, she is asking questions about how it exists and flourishes amidst complex political, social, and physical environments. Critical of a desire for assimilation that is often associated with certain ideas of visibility, Tse writes that she wants to “expand on what queer language can include, to make images from a multi-valenced approach that operate outside of the bounds of simplification.”

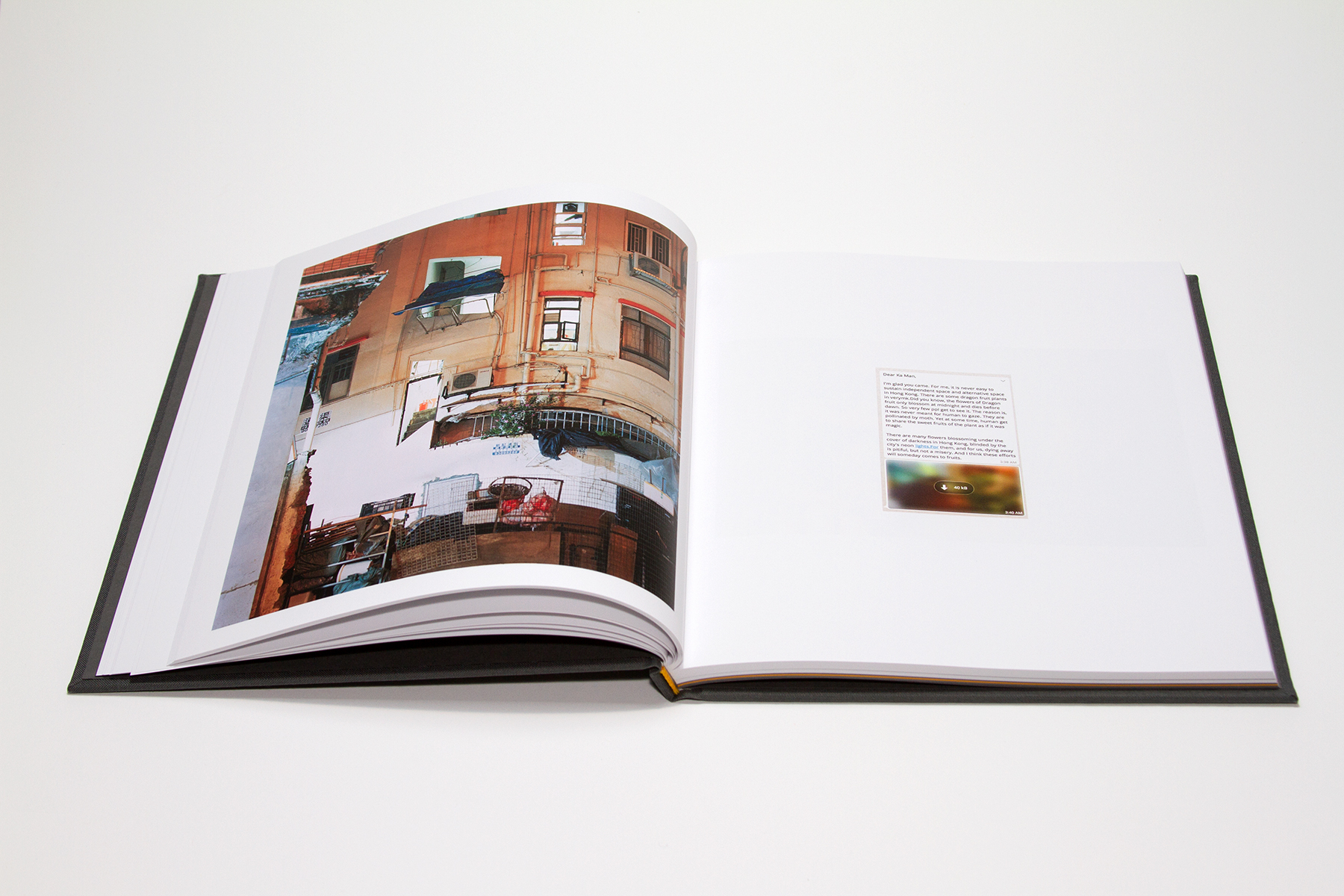

Although many of the photographs in the book take place outside or in public environments, we are also invited in to several of the subjects’ personal spaces, witnessing private moments in their homes, kitchens, and bedrooms. Some of the more intimate moments take place under the cover of night, or at dusk, the magical hour when the sun begins to fade and an entirely different world is becoming possible. These images take on an additional metaphorical meaning through Tse’s inclusion of a message she received from one of her subjects, which reads:

Dear Ka Man,

I’m glad you came. For me, it is never easy to sustain independent space and alternative space in Hong Kong. There are some dragon fruit plants in verymk. Did you know, the flowers of Dragon fruit only blossom at midnight and dies before dawn. So very few ppl get to see it. The reason is, it was never meant for human to gaze. They are pollinated by moth. Yet at some time, human get to share the sweet fruits of the plant as if it was magic.

There are many flowers blossoming under the cover of darkness in Hong Kong, blinded by the city’s neon lights. For them, and for us, dying away is pitiful, but not a misery. And I think these efforts will someday comes to fruits.

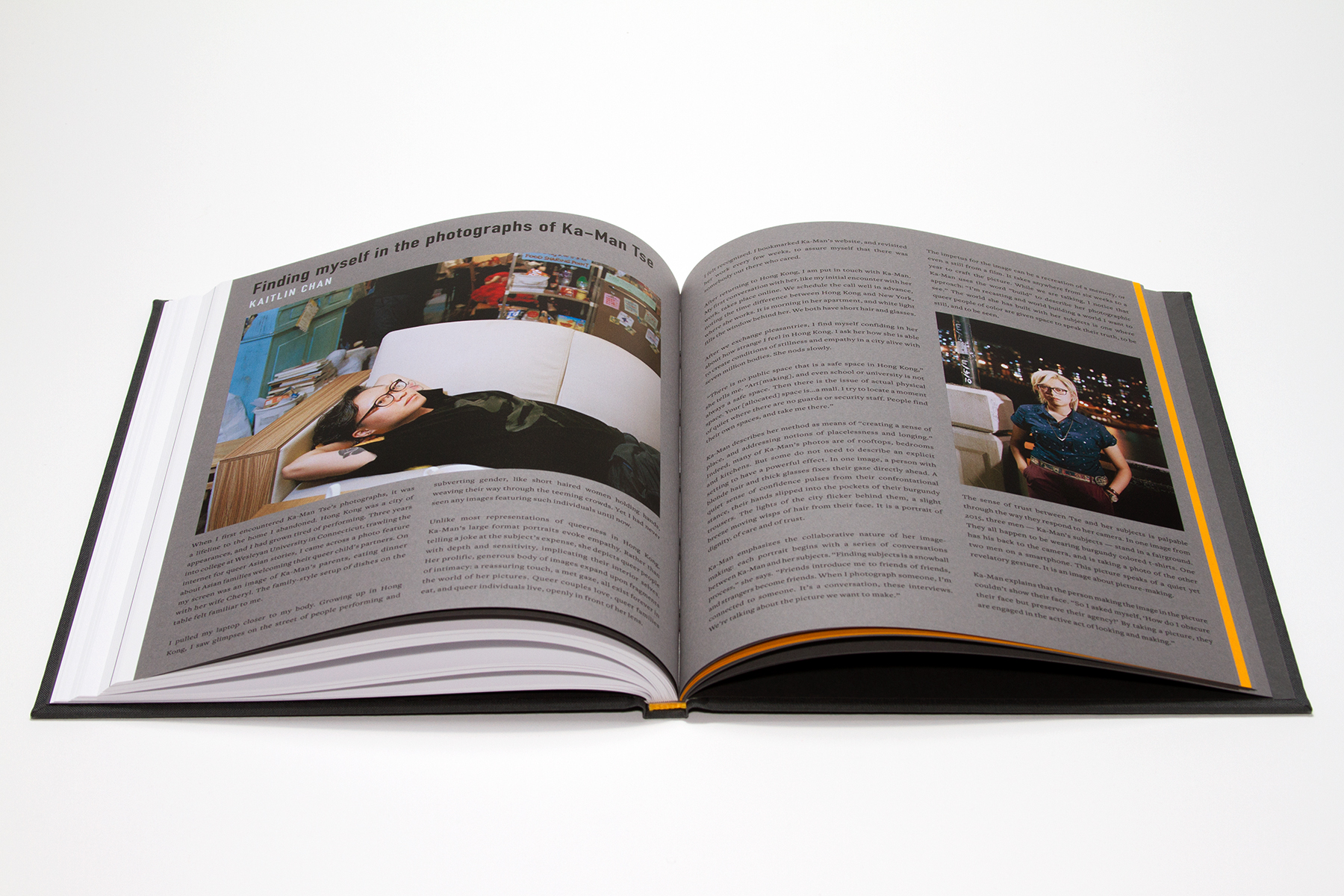

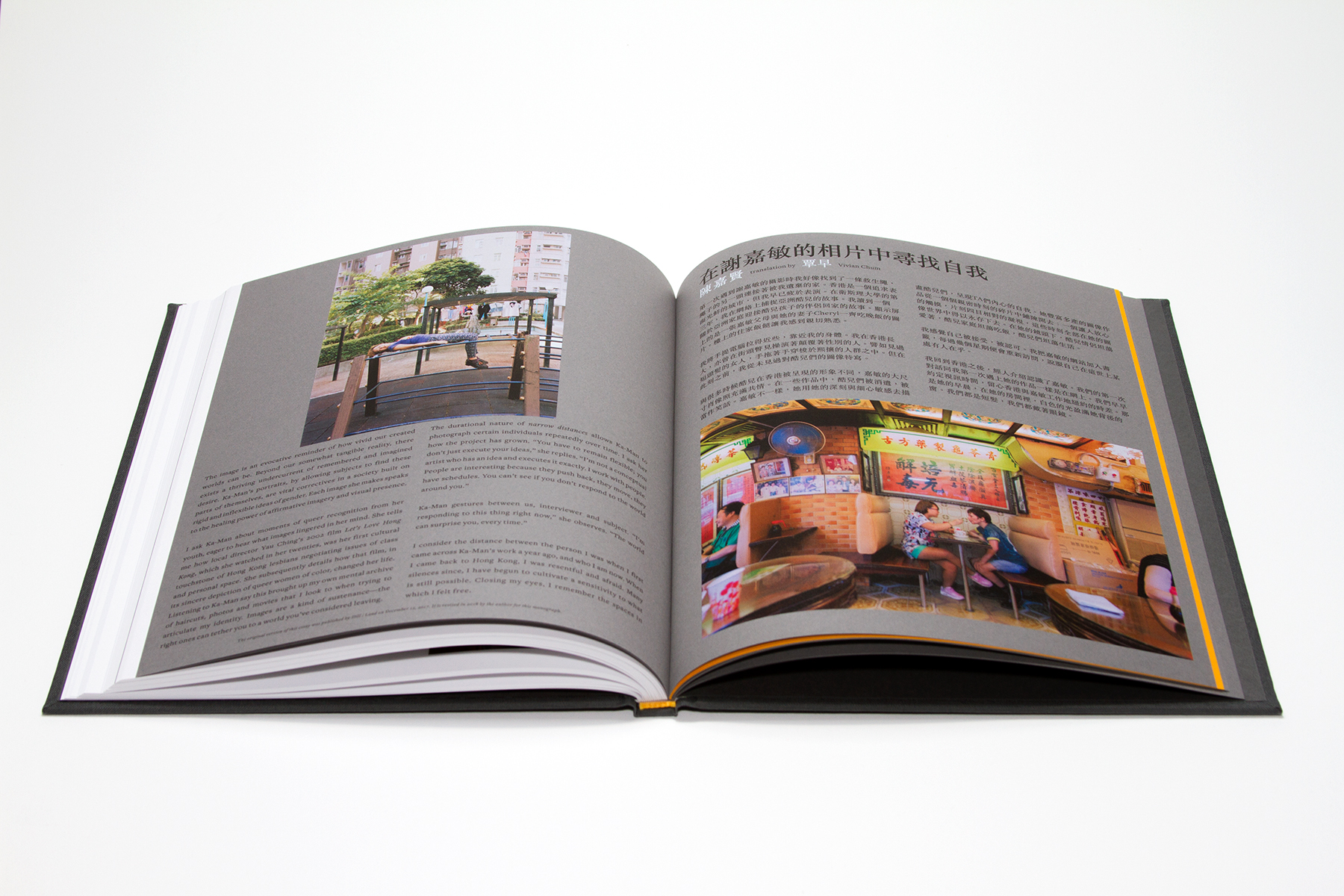

As in this message, Tse’s images both respond to the present while imagining possibilities for a different future. In her essay, Finding myself in the photographs of Ka-Man Tse, Kaitlin Chan beautifully summarizes Ka-Man’s work and the strength of this imagining:

Ka-Man uses the word “build” to describe her photographic approach: “I’m recasting and world building a world I want to see.” The world she has built with her subjects is one where queer people of color are given space to speak their truth, to be still, and to be seen.

Visit Candor Arts to order.

All images courtesy Candor Arts