Book Review: kristine potter’s “Manifest”

By Jess T. Dugan | November 8, 2018

Published by TBW Books in 2018

Embossed paperbound hardcover with tip-on front and verso

92 pages / 48 Duotone plates / 9.5 x 11.25"

Afterword by Stanley Wolukau-Wanambwa

Our cultural myths surrounding both masculinity and the American West are so pervasive that it can be difficult, at times, to remember that both are fabrications, reductive and fantasized versions of the real thing. Kristine Potter’s newest book, Manifest, explores these myths through the men and the landscape of Colorado, where she photographed between 2012 and 2015. Potter’s earlier work, The Gray Line, explored similar ideas of masculinity and belonging through her portraits of young military cadets, often pictured immersed in the landscape and rendered with a strong but tender light, a strategy she carries through in Manifest.

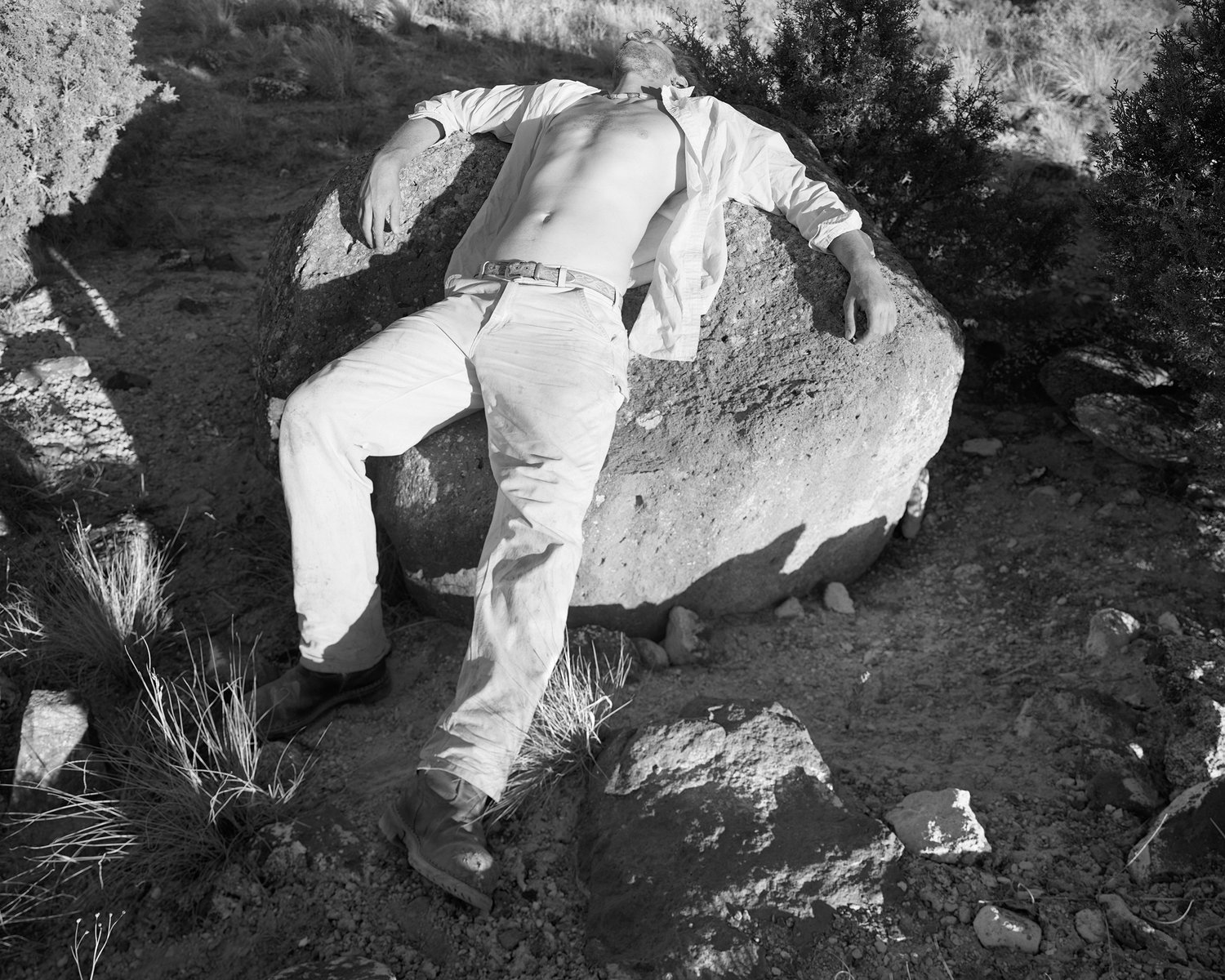

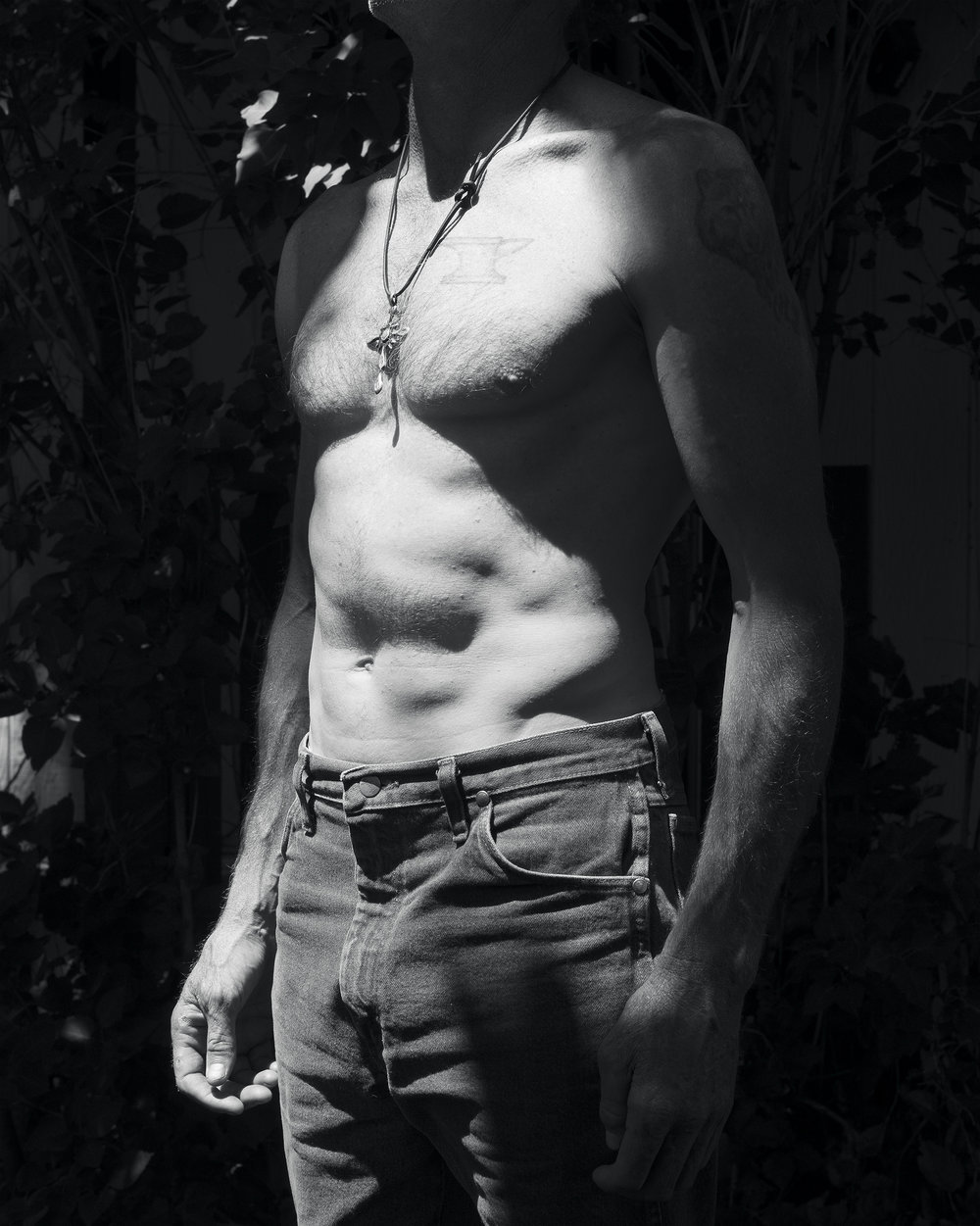

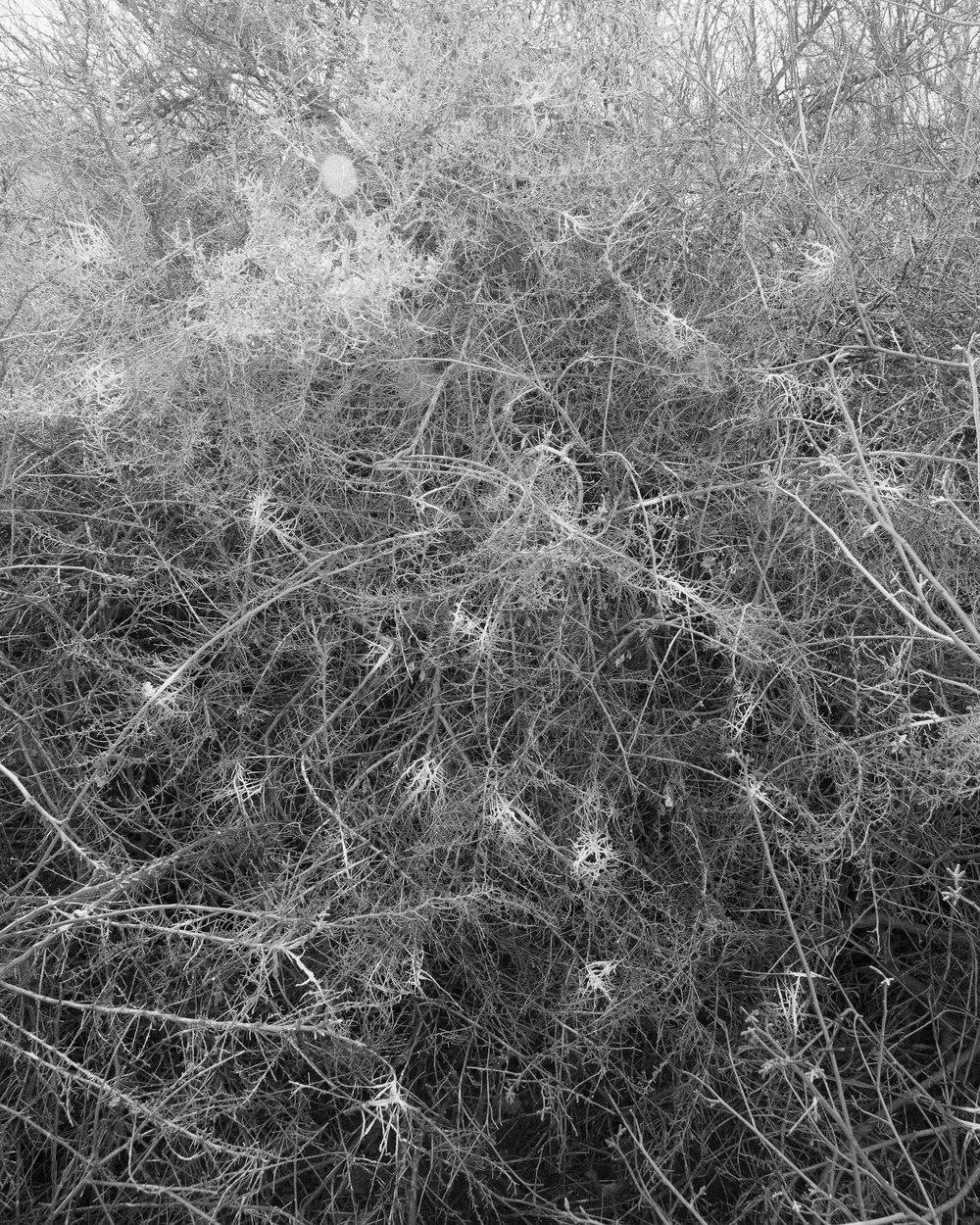

The book begins with an image of a man laid back on a rock, his shirt open to reveal his skin. It is at once sensual and vulnerable, a reversal of the typical male gaze we have grown so accustomed to seeing. The light is direct and harsh, and the resulting image is formally rigorous, carefully composed of areas of intense light and shadow. Although the man’s face is obscured, it is clear that Potter created a sense of trust and collaboration with him in order to make his portrait, which so elegantly sets the tone for the book. Following this image, and throughout the book, there are images of the landscape, yet they’re not the typical vista-style images we’re accustomed to seeing of the West. Instead, they are made in much closer range, often focusing on the dry, barren, or rocky ground. They are subjective, referencing a personal vision rather than a national ideology. They set the stage for the portraits in the book, providing a context for where these men live and spend their time, largely in isolation and away from the trappings of the modern world.

There is a poetry to the images; the book flows energetically rather than in service of telling a specific story. Potter leaves room for the viewer, not inserting herself too forcefully into the narrative, although her presence is felt throughout.

One of my favorite images depicts a man lying on a bed, which appears to be handmade, inside of a tent, bins of his belongings beneath him. This image references an existence often associated with independence and ruggedness; the notion of a man surviving off his wits and the land alone is deeply embedded in our shared imaginations. Yet, his pose is open, gentle, and vulnerable, his hand extended above his head and resting delicately off the edge of the bed. Potter is asking us to reconsider our notions about masculinity, asking us to see her subjects as the more complex versions of themselves than traditional depictions or assumptions allow. Potter’s approach to her subject matter – both the men she photographs and the landscape of the West – is tender and subjective, a far cry from other work, often by male photographers, on similar subjects.

The writing by Stanley Wolukau-Wanambwa at the end of the book adds a poignant, essential component, providing a framework for the ideas and questions explored in Potter’s work while also positioning her work within a long history of both portraiture and landscape photography. Wolukau-Wanambwa writes that Manifest recalls for him, “the placelessness of Richard Avedon’s scene-less white backdrops in In The American West, most especially in those portraits of the coiled and corrugated forms of wounded white men.” He ultimately asks, “Is any of this West something other than illusion?”

He closes his essay with arguably the central tenet of the book, an idea that is both urgent and important at this moment in time:

“Potter’s portraits decouple autonomy from authority, cleaving the symbolism of the western male from his proper cultural function. In this disjuncture, it becomes increasingly apparent that the scope for a return to the halcyon days of unchallenged male supremacy can be reduced, and that this can be done using the self-same logic and symbolism with which that supremacy claims its inalienable rights. Indeed, over the course of Potter’s photographs, this final frontier, this hoary myth, this last bastion, this male preserve of the American West comes unmoored.”