Book Review: “From Here to Eternity” by Sunil Gupta

By Rafael Soldi | September 8, 2022

Edited and introduced by Mark Sealy

Designed Fraser Muggeridge Studio

2020, 196 pages

Dimensions: 8.2 x 11.7”

Softcover (thread sewn)

At the outset, Sunil Gupta’s From Here to Eternity—published by Autograph ABP in conjunction with his retrospective by the same name at The Photographer’s Gallery—has a personal and informal quality to it. The softcover publication is magazine-size, with soft and pliable uncoated pages that make it easy to flip through it as if it were not precious. This book maps the encounters and events that chart Gupta’s political and personal journey through a range of photographs, documents, ephemere, and hand-written notes and reflections.

On the cover we see a young Gupta pointing a camera directly at the viewer—one eye covered by the viewfinder and the other open and defiant gazing out at us. But one quickly realizes it’s a self portrait in a mirror, the gaze is also on himself. Gupta’s practice is similarly split—on one end he looks at his own life with a sensual, emotional, and empathetic gaze, and on the other he looks at the world through a lens of political activism and defiance. "What does it mean to be a gay Indian man?,” Gupta asks, “ This is the question that follows me around everywhere I go and is still ever present in my work." For nearly five decades, Gupta's lens has examined issues of family, race, migration and the complexities and taboos of sexuality and homosexual life.

As the title suggests, From Here to Eternity is about time. The 1974 Gupta on the front cover is directly opposite the 2020 self-portrait on the back cover, which pictures the artist’s torso with medical devices attached to it, captioned “Having heart rate monitor installed.” It’s clear from the start that with this document, Gupta invites us to participate in his personal, political, and artistic evolution. Inside one finds colorful pages in bright red, pink, orange, yellow, and green peppered with snapshots, postcards, letters, posters, and news clippings collected during his long career in photography and activism. Each item is captioned in the artist’s handwriting in an informal and narrative way. Everything is dated, and the story begins in 1974 with a photograph of an early gay liberation protest in Montreal. Gupta’s work “has been instrumental in raising awareness around the political realities concerning the fight for international gay rights and of making visible the tensions between tradition and modernity, public and private, the body and body politics.”

The only glossy pages in the book are dedicated to an essay by distinguished author Mark Sealy, Director of Autograph ABP and curator of Gupta’s retrospective. Sealy begins with a simple “I’ve been talking with Sunil Gupta for over 30 years, if not more.” Setting the tone for the conversational nature of this publication. He continues describing Gupta’s “infectious sense of ease concerning turbulent pasts and intersections with pleasure.” Noting that “[What is interesting about] an artist like Gupta is the point where things began and the catalytic moments of making [that push one] to choose a life in and with politics.”

“At the soul of Gupta’s practice,” Sealy notes, “...is the idea of family, real or imagined.” The fragmented ephemera charts Gupta’s deep and powerful relationships in moments of protest, in the black arts movement in Britain, in queer communities in India, and with his own family. What emerges is a moving portrait of the artist’s struggles, achievements, and a life lived through the complex politics of social change.

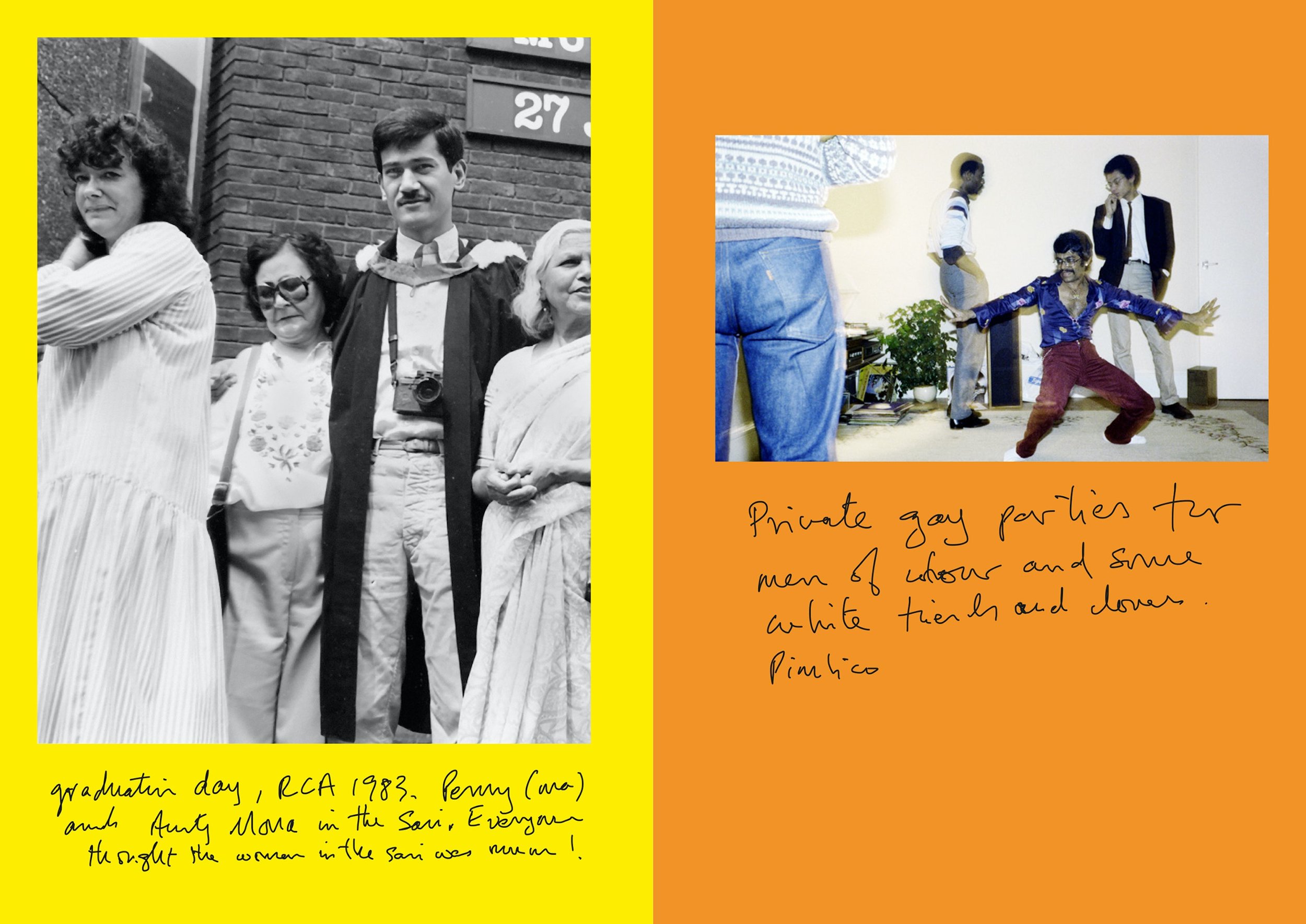

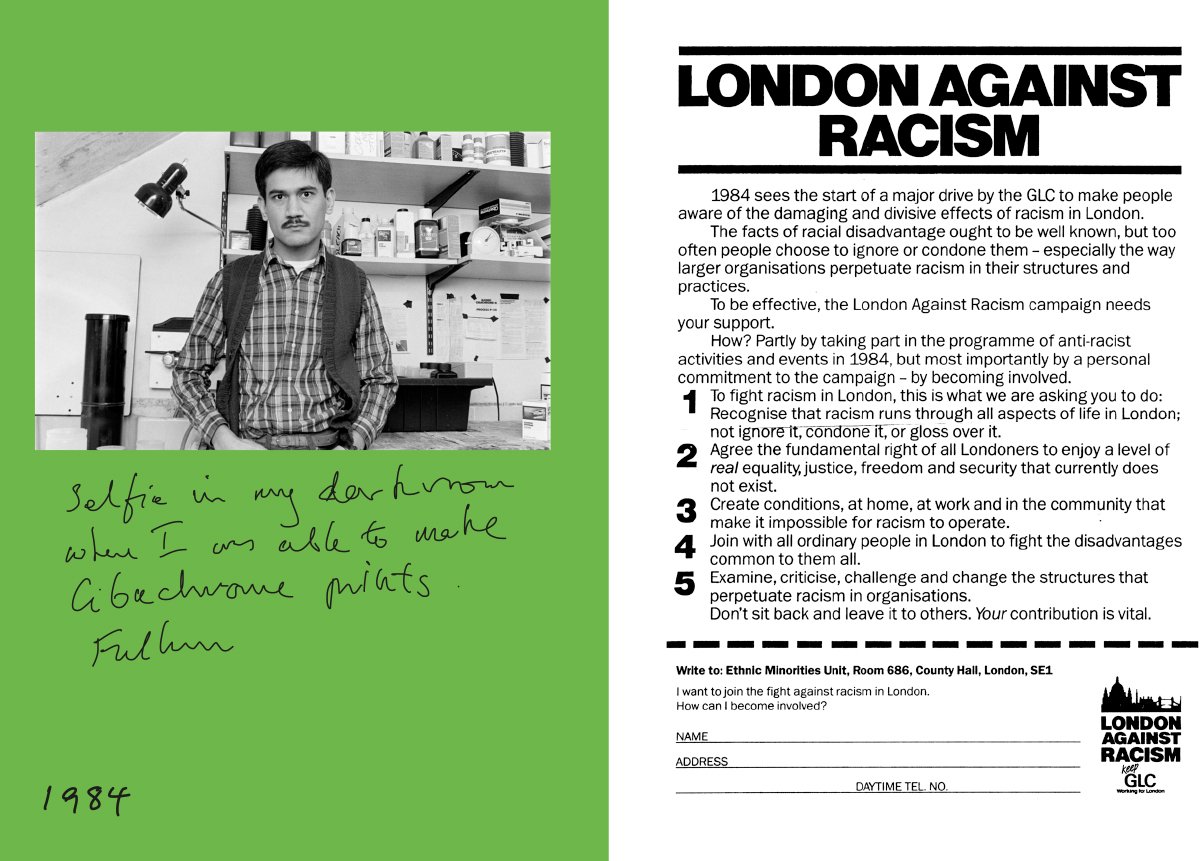

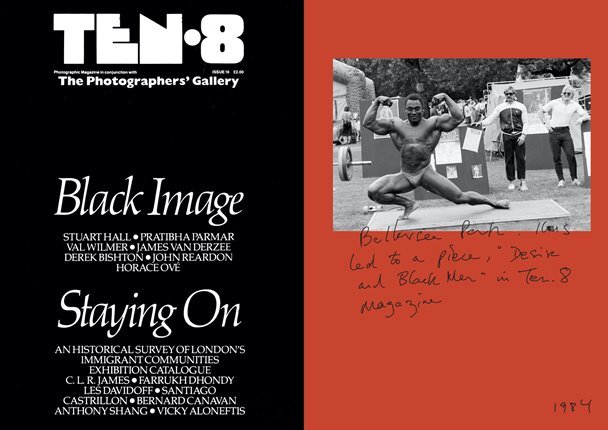

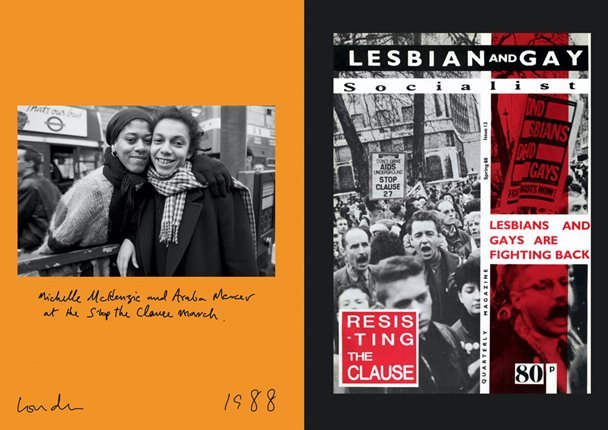

In an early page we see a contact sheet of Gupta’s now-famous Christopher Street pictures from 1976. A few pages later, a 1980 self portrait opposite a blown-up reproduction of a TIME magazine cover that reads “How Gay Is Gay?”. Curiously, he captions all self portraits as “selfies,” a contemporary term that would not have been in use at the time most of these images were made. I enjoyed this verbiage because it clues us into the fact that these are contemporary captions, in a way they act as a memoir and first-hand recollection of life as he remembers it in this moment. A snapshot picturing young men dancing reads “Private gay parties for men of color and some white friends and lovers,” while a 1983 portrait of him as a young student at the RCA’s photography department with Emily Anderson reads “...2 out 7 students being queer then was a good ratio. We’ve been close friends ever since.” As the book progresses we continue to see his family, friendships, and a range of documents, exhibition announcements, and correspondence that track Gupta’s growing recognition and activism. For example, a 1986 flier promoting Same Difference, an early LGBTQ exhibition organized by Gupta and Jean Fraser at Camerawork.

The pages move us through Gupta’s accomplishments and milestones, with the early 90’s ushering in the AIDS crisis and Gupta’s own diagnosis. He ages, his relationship with India deepens, and he becomes an internationally sought-after artist. But his commitment and focus persists, evident in a 2008 curatorial statement he writes titled Queer Families—Portraits of Kinship, where he describes chosen families that go beyond kinship. “Ones that challenge the rules—legal, cultural, economic, and social. Ones that establish new sets of relationships, different ways to live our lives. Ones that deserve to be taken seriously and celebrated just as much as the traditional family.” The book ends with a portrait of Gupta and his husband on the beach, printed on the pages of The Guardian.

From Here to Eternity is about now, about then, and about forever. It is as much about the finite moments—the “Here”—that make a meaningful and layered life in art and political activism, as it is about the deep magic of queer and Black* kinship that is and feels eternal. As a queer artist I am grateful for Gupta’s generous invitation into his personal archive. Here lies a footprint for living with joy, anger, and courage in the face of oppression at the edge of a rapidly-changing world.

*In the 1980’s London there was a shift from using the term “ethnic” to using the term “Black” to refer to Black and South Asian people, Gupta describes it as “part of that postcolonial moment.” Throughout, this is the term that appears in Gupta’s many projects in collaboration with colleagues of color, and thus I am using it as such with that context.