Q&A: Ian Lewandowski & Anthony Cudahy

By Rafael Soldi | April 8, 2021

Ian Lewandowski (born 1990) is a photographer from Northwest Indiana. He presently lives and works in Brooklyn with his husband Anthony and dog Seneca. He also archives the photo work of Kenny Gardner (1913-2002).

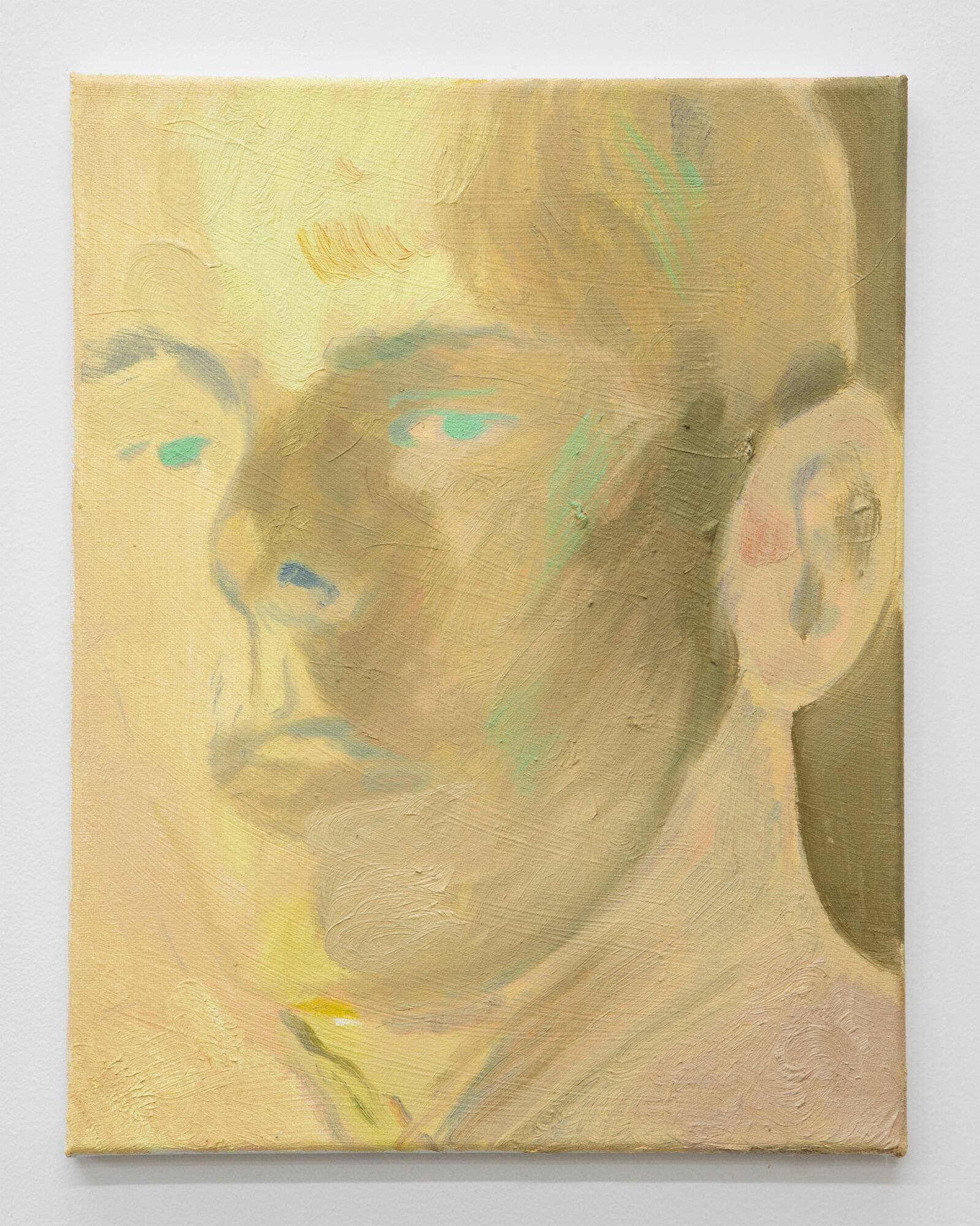

Anthony Cudahy (born 1989) is a painter living and working in Brooklyn, NY with his husband, Ian Lewandowski and dog, Seneca.

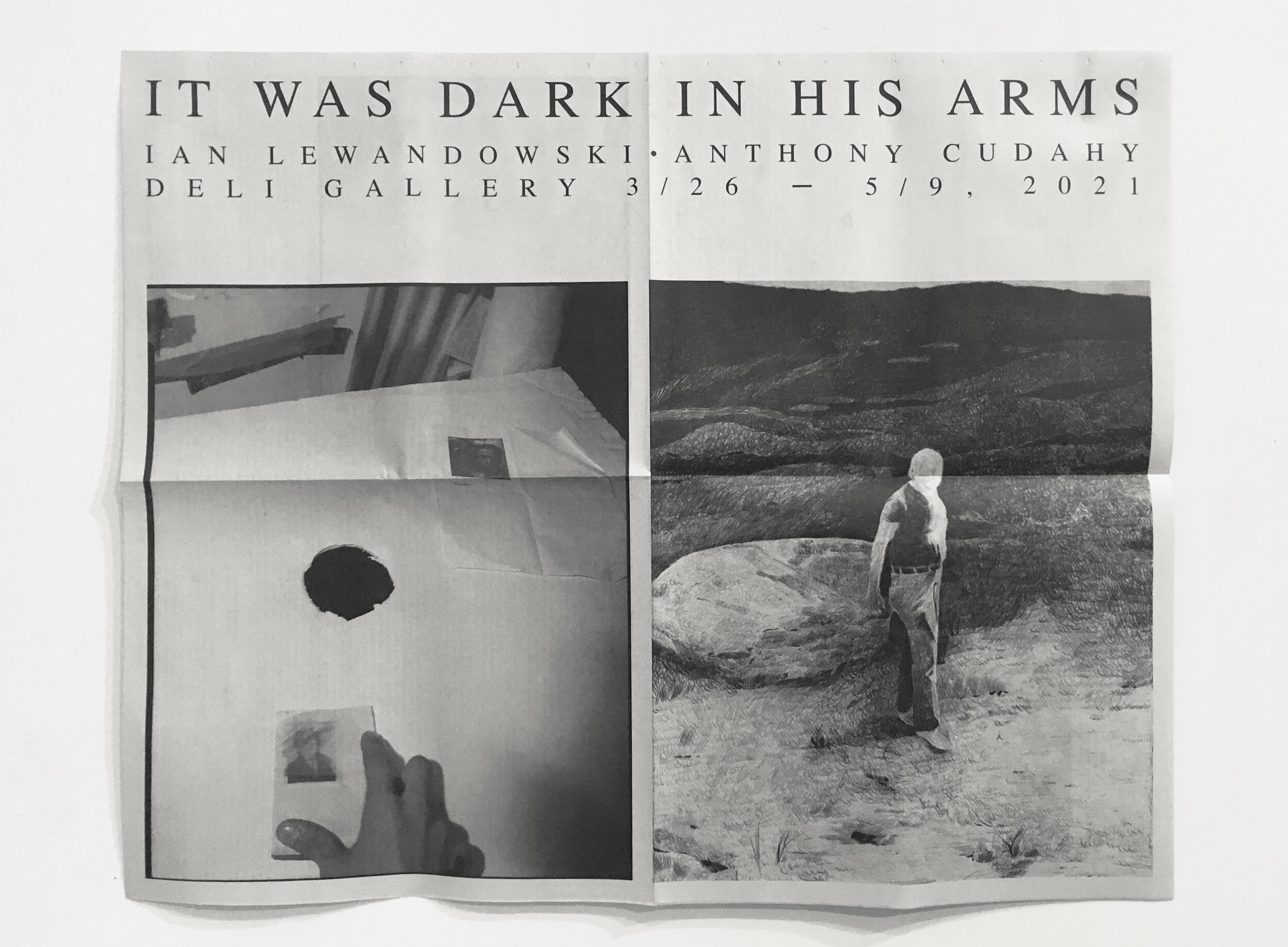

This interview was conducted on the occasion of Ian Lewandowski and Anthony Cudahy’s exhibition, It Was Dark in His Arms, with Kenny Gardner, on view at Deli Gallery on March 26–May 9, 2021. The interview appears in a broadsheet publication that accompanies the exhibition.

It Was Dark in His Arms, at Deli Gallery. Images courtesy the artists and Deli Gallery.

Rafael Soldi (RS): Who was Kenny Gardner?

Ian Lewandowski (IRL): Kenny Gardner was a singer in The Royal Canadians, Guy Lombardo’s orchestra. Guy was Anthony’s great-uncle, and Kenny was also married to Guy’s sister Elaine. He was a WWII veteran and unofficial photographer for the band, and later in life a volunteer firefighter in Long Island. He was—like I’ve been among various groups of friends and relatives throughout my life—the photographer of the family, seemingly having either a twin-lens reflex or 35-mm SLR on him at all times. Kenny died in 2002. I only know Kenny by way of his photographs, which has so far proven to be the most challenging part of being his archivist. While his archive reveals a steady commitment to photography over five decades, the word photographer is not present anywhere in my research on him.

Anthony Cudahy (ALC): Kenny was one of the only members of that generation of my family that I knew in my childhood. We would visit him at his home on Long Island, and he would visit us in Florida. He had Alzheimers, so I feel like I was able to glimpse many sides of him that would come through briefly, but never was able to gather a full picture. He was a funny, kind man, but would occasionally have war flashbacks, or get lost in thought and start to weep. He also kept every drawing I ever gave him in its own drawer in his office. He passed away when I was in 8th grade and we spent the following summer trying to sort his belongings and empty his house.

RS: How did Kenny become part of both your art practice?

ALC: After his house was sold, we saved his 50-plus-year archive of photographs and papers and brought them back down to Florida with us. My aunt at various points scanned some of the film, but mostly it waited in bins. There were images that I painted from the various contact sheets over the years.

IRL: In 2017 I asked Anthony’s mom and aunt if I could look through Kenny’s negatives, if only to organize and secure them under more archival conditions. At this point I wasn’t thinking of Kenny’s photographs having anything to do with my own. The negatives were mostly stored in wax paper envelopes in which Kenny originally received his film from the photo lab. Some were labeled with dates or locations, or simply a theme or recollection: “Politics” or [sic] “Girl Who’s Camera Broke”. The mechanical task of inserting strips of negatives into archival plastic sleeves afforded me the chance to really look at each and every one of his photographs. I think other avid viewers of photographs can attest to the pleasurable act of looking, in my case on a mini light table with a loupe amidst the early cases of COVID-19. While many of my own plans for photo shoots were dampered, I was fortunate enough to be able to stay home to do this looking.

ALC: When Ian began to select the photographs that now stand in for Kenny’s catalogue, scanning and spotting and color-correcting them, the images began to live in my mind in a more active way. Images that I had previously only viewed tiny, on low-contrast contact sheets, were now deep and detailed.

Over the summer, I read an essay by Chris Kraus, titled "Posthumous Lives" (1999) that really resonated with the work Ian was doing to preserve and spread Kenny's work. In it, Kraus considers artists who protect and propagate the ouvres of their deceased friends. She details Penny Arcade's successful efforts to save Jack Smith's legacy, but what felt closer to Kenny was her continued efforts with the still comparatively unknown photographer Sheyla Baykal, whose work she stored in a rented backroom space of a LES jewelry fabricator. Baykal was friends with Paul Thek and Peter Hujar and photographed that group of artists excessively, but when she passed there was no money to preserve her life's work. Kraus insists that Arcade's efforts are what keeps Baykal's legacy alive. I think another way Kenny's legacy lives on is by the images entering a conversation. While his photographs had sat waiting for years, now there are two artists engaged in conversation with them. Directly or indirectly, artists are always working in dialogue across time with past artists, and that’s what keeps a legacy alive.

RS: That’s an interesting perspective. Looking through my notes from a prior conversation, I have you quoted as having said that “the past is not fixed” in the context of entering a dialogue with archives.

ALC: I think the past is clearly a force on the present, but that we in the present also enact pressure on the past. Each time we reconsider the past with a new perspective we change it. Obviously a lot of artists/writers/theorists are engaged currently in critical fabulation (Saidiya Hartman’s term, specifically focused on Black lives), which is a framework I was discussing with you previously about engaging with archives.

RS: Each of you relate to Kenny in different ways. Can you expand on that?

IRL: My entrypoint has mostly been, while certainly quite different, Kenny’s and my shared practices as photographers. Similarly to Kenny I also married into Anthony’s family. This is always a point of argument among photographers, but I feel a unique and special feature of the medium is the tendency toward observation, the ability to both retain some kind of vantage point from which to make the photographs, while still holding an active participatory role. In looking at the pictures I see Kenny’s decision-making, his engaging with subjects, his moments of shyness, confidence, his belaboring, obsessing, being too precious, just the same as I do when I take pictures. This sounds like a no-brainer, but looking at his pictures also reminded me about photography’s completely unique ability to address time. I will witness the birth and first steps of family members now in their 60s, and then a few minutes later they are an adolescent, and then there they are holding their first child. In this way it’s deepened my connection to what is now an extended family. It’s so easy to forget how so complex, yet dumbfoundingly simple a tool photography is.

ALC: Kenny's photographs, to me, make up an expansive image world that encourages collaboration. In general, when I'm considering images and browsing my own varied collection, I'm trying to find small moments, details, and gestures that spur a narrative or even just a color idea. Working through his images in this way, I begin to fixate on his eye and what interested him within the composition. Making collages and then paintings from his material feels like a new way to relate to him.

RS: Anthony, I love that you called it an “expansive image world.” You’ve worked with archives in the past, discovering or creating a universe that sits somewhere between your paintings and the reference images. It may not always be apparent, but your work has a deep relationship to photography already. How is your collaboration with this archive different or the same as others you’ve mined?

ALC: It’s funny because in a way it’s just as mysterious as working from an unknown source, or from various vernacular photographs collected into something like the ONE National Gay & Lesbian Archives, which I do often. I say mysterious because I don’t know the true context or full picture of the scenario, even if I know the subjects of the photographs personally. It’s an alienating closeness, which I think is what sentimentally has always drawn me to photography.

RS: In the context of artistic production, how does what you do differ from what Kenny was doing

IRL: I don’t know whether Kenny considered himself an artist. That current artist-photographer distinction is one that feels increasingly fruitless to me, but I think it’s relevant to consider such workflows when looking at Kenny’s photos, especially given the time and context in which they were made. To be honest Kenny seems more fearless than me when I compare the two. I’m not sure whether it’s the baggage I carry as a photographer trying to work in a fine-art context today, my education, or just a difference in our personalities, but I marvel at the generosity of his gaze.

RS: That’s interesting. Perhaps that’s why vernacular photography is in such high demand right now. There is a hunger for that lightness of being around a camera that is so hard to come by today. We see cases like Vivian Maier, for example, who photographed in such a spirited nature, unburdened by the weight of an art career. She was a far better photographer than Gary Winnogrand, for example, in my opinion.

IRL: Yes! I’m always thinking about those distinctions around photography, or, let’s say, photographic material. I think perhaps the history of the medium lends itself to such categories; art, snapshot, advertising, porn, etc. I think in certain ways this does, to use your word, burden photographers to a certain extent. I suppose any visual material encounters this since it’s all subject to appraisal. I try to ask my students about this and find it’s helped me build more of a language around this argument. Bearing in mind they are in a photography program within an art college, I like to ask them, out of genuine inquiry, does photography need art? Does art need photography? Are they two different things entirely that should be treated as such? Personally, I certainly work under the auspices of both, but I find that the moments I’m able to let go of that umbrella of “art”, my whole world opens up.

RS: Is this your first show together?

IRL: Yes, and it feels like an appropriate coalescing of years of conversations about photographic images. I think our reverence of and attention to photographs is a foundational aspect to both our works.

ALC: I don't know what it looks like from the outside, but to me our practices are so intrinsically woven together it's difficult to know where our shared influence on each other starts or ends. We work through each others’ pieces together in actual dialogue or just proximity. In both cases, our work is really invested in the consideration of an image’s source and following its spark of inspiration intuitively.

RS: I'm sentimental, and I think that’s very beautiful. But that also sounds productive. Earlier we talked about Anthony’s relationship to the archive and photography in past work. Are there more specific examples of how your work has influenced one another’s? Is this apparent in any of the works in the show?

IRL: We have moments of overlap certainly. I think working in the same room has made that inevitable. I naturally respond to images that dominate or occupy my immediate visual space, so it was no surprise when Kenny’s pictures entered my radar. Recently Anthony painted a knife into two or three of his paintings, and it sort of made me more keen to photographs I was encountering containing sharp objects or knives. We both had this mutual understanding and fascination with a sort of violent but protective gesture… just one example!

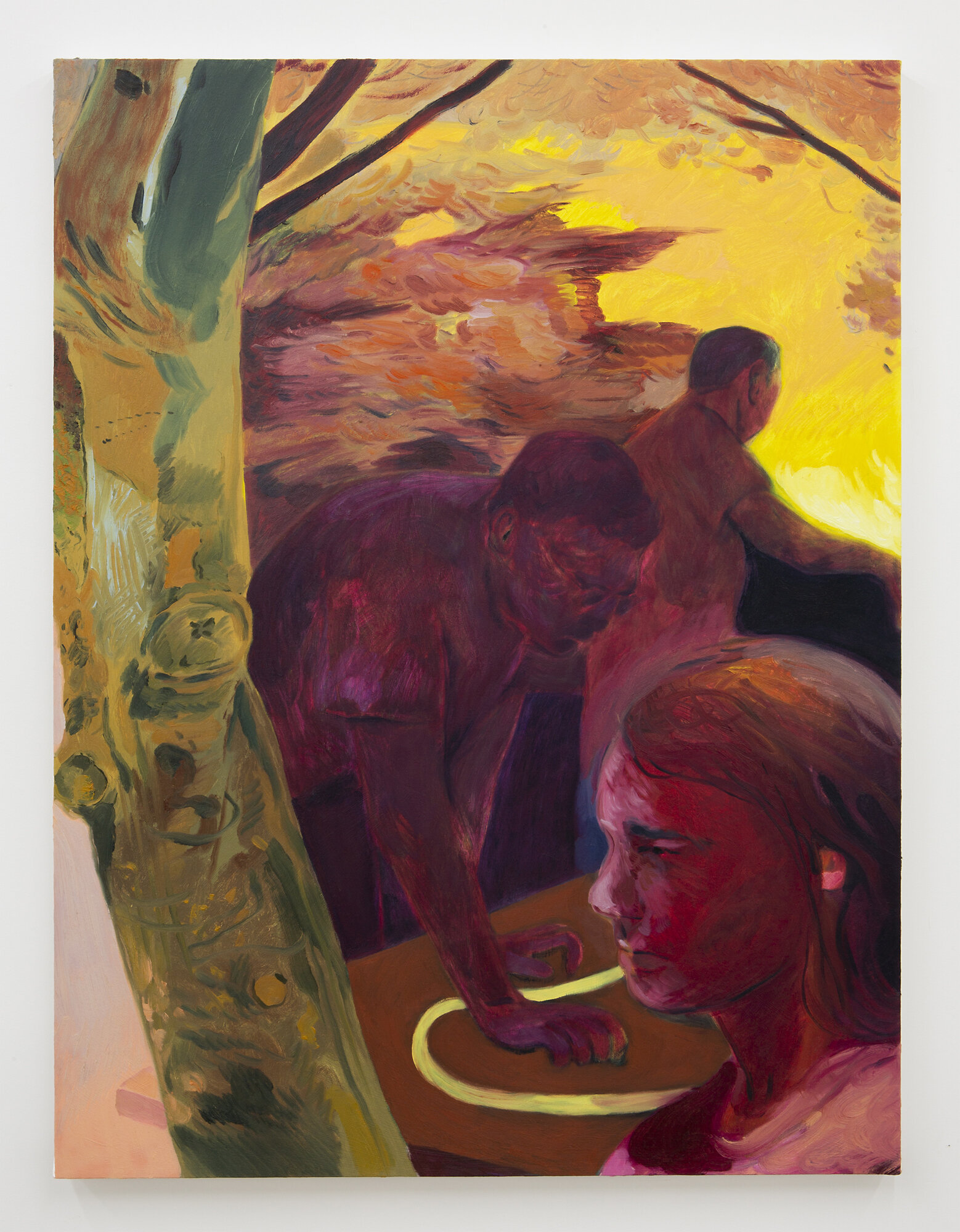

ALC: Two of the paintings in this show feature figures that are compositionally framed by other figures, which was something that later I realized in several other Kenny photographs that Ian had fixated on and made prints of… that way of setting up an image had wedged itself in my brain and I didn’t realize until after finishing those pieces.

IRL: Yes, I similarly identify with this occurrence of Kenny’s picture elements wedging themselves into my brain when I go to take my own pictures. It’s unconscious.

RS: Is this a two-person or a three-person show?

IRL: Great question! It’s been eluding us whether Kenny is the third artist in the show. In a way, yes, absolutely. I don’t want to write his work off as simply “artifact” or “archive”, or something that leans against my and Anthony’s works. His pictures feel so alive and present to me, perhaps because many have never been seen by a larger photo-viewing public. At the same time, it’s a question of Kenny’s intent with his work, which certainly could be a different set of concerns than my own. It’s tricky to do this, but I want to handle Kenny’s work in such a way where I, a fellow photographer, am engaging not in revising or manipulating a narrative, but rather in a “conversation with the past,” to quote the playwright Donja R. Love. This is ultimately where I land with it.

RS: This question of Kenny’s intent or potential approval/disapproval of the fate of his archive seems to weigh heavy on you. There’s no way to know, obviously, but here he is, in a show with you. How are you feeling about it? Does this question make you anxious, or are you at peace with it

IRL: I do have moments of anxiety over it, but I know Kenny’s images are strong and can hold their own. I’m a believer in a work’s autonomy outside of its creator. Kenny’s pictures are part of the world now, and ensuring that is perhaps the primary function of my role. I’m at peace with the decisions and selections I’ve made, though I tend toward doting and being overly precious.

ALC: I understand all of Ian’s concerns and appreciate his caution, but from my vantage point I’m only excited to see Kenny’s work out in the world, on instagram and now printed and hung at Deli.

RS: We’re having this conversation as the first year of the COVID-19 pandemic comes to a close. The ways in which this event has touched the world are immeasurable. I hate to ask the obvious, but how has COVID-19 affected your practice and this project in particular?

IRL: In a more concrete sense, this global health emergency afforded me time and ability to ruminate on these pictures. Several professional opportunities fell through for me in March, but I work a day job that wasn’t such a stretch to do from home. Having a crappy health history, I was very fortunate to have that ability, and furthermore to work on Kenny’s archive. Reflecting back now, I’m realizing how the context of the pandemic, the Black Lives Matter protests, and the rollout to the presidential election—all happening simultaneously—permeated my looking. There’s a haunting picture in Kenny’s archive of a man measuring the distance between a video camera and a singer on a stage, so as to focus the lens for a live recording. I also found myself honing in on pictures containing clocks, wristwatches, and TV screens with images of JFK or George Bush Sr. or MLK Jr. It wasn’t a coincidence when these objects ended up in my own pictures.

ALC: My life from March on has been only at home or in the studio. I funneled a lot of anxiety into just working, and ended up finding a steady pace where I’m currently painting more than ever have. Whenever you’re in that position I feel like your work can grow and change at a quicker pace. I’ve felt in the zone in painting, and nowhere else in the world this past year.

RS: After all this time going through the archive, have you made an edit of “final” images? How many images are in this group? What criteria did you use?

IRL: At this point, after about three years of work at it on and off, I have compiled a portfolio of 210 “final” photographs of Kenny’s. I know this is so subjective, but the goal of the portfolio is to represent the well-rounded practice of photography I see that Kenny maintained over roughly 50 years, to attempt to get at that unique language I see him formulating throughout his life.

RS: Let’s talk about something that is a little more complicated—the biases and contexts that you bring to the reading of these images. We’ve talked about queerness for example, which is central to both your work. Can you be objective? Do you have to be objective? How does your own language contaminate Kenny’s?

ALC: My process is definitely not objective, and honestly is very insular. I have to trust that what I am making will resonate with a viewer despite maybe not being explainable. I also have to trust impulses that may be considered queer—romantic brushtrokes and emotional color—and not self-censor them. So I think the final pieces end up pretty far removed from Kenny’s vantage point, but that’s part of what makes working with this source interesting for me.

IRL: I don’t believe anyone can be objective. I believe my own language, my own sensibility, certainly contaminates Kenny’s, but so does any viewer’s of any photograph. What’s easier for me to wrap my head around is trying to enter the viewing experience with empathy and compassion. Being a gay man I’m inevitably going to digest a photograph of two men lounging together in a (their?) backyard under different circumstances than it was likely made, but I’m okay with that potential misunderstand, and even relish the medium’s unique ability to accommodate it. There’s a word I recently learned, mondegreen, which means a mishearing, and subsequent misinterpreting, of a song lyric, such that it creates new meaning. The author who coined the term experienced this as a child when her mother sang her a lullaby with the lyric “laid him on the green”, which she heard and understood through her life as a new fictitious character “Lady Mondegreen”. More than some kind of retroactive wish fulfillment or “queering” of the past, I’m so much more interested in this kind of imaginative, perhaps conscious, misunderstanding as a means for new significance.

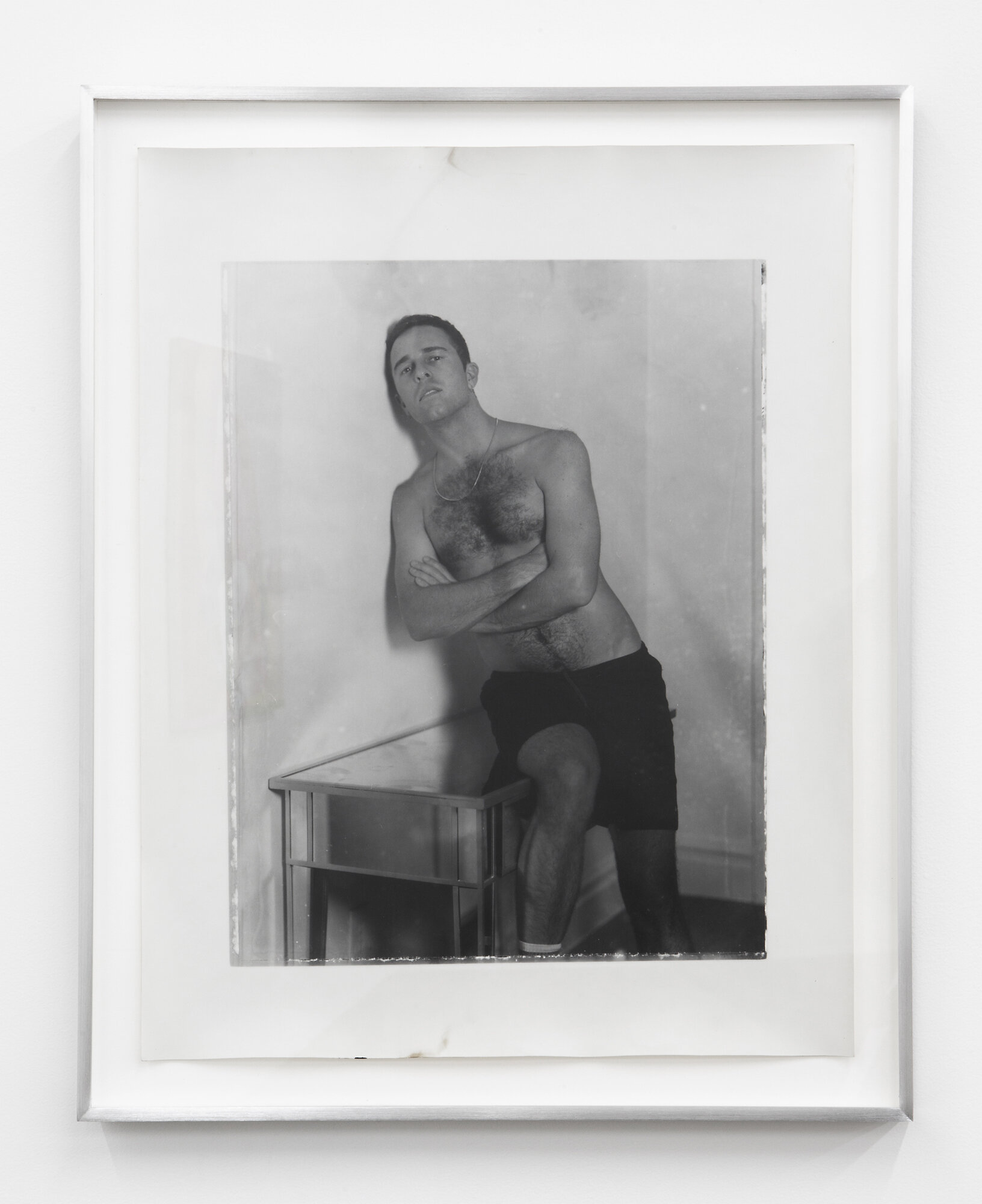

© Ian Lewandowski, Couple, 2021

Gelatin silver print (Ilford RC postcard), 6 × 4 inches

RS: On this note. Ian, you’ve touched on this a bit earlier. As a photographer, did Kenny’s language contaminate yours, too?

IRL: Absolutely it did. I’m admittedly very impressionable when I look at photographs. When making my own pictures, I naturally respond to, mimic, “quote” existing ones I encounter, so with Kenny’s work it was no different. I’ve found myself responding to his pictures, having spent so much time with them, following up with genuine inquiry. A sustained and continued looking at this extensive pool of images has made a significant impression on me. It’s exciting to see this play out when I see my film for the first time after it’s processed.

RS: I’d love to end on your joint self-portrait, which I think relates beautifully to the title of the show. It does not feel far from the kind of portrait Kenny would have made of you two. This image is available for purchase as a gelatin silver print postcard in a limited edition of 50 to benefit STOP AAPI Hate.