Q&A: Alice Gosti / The High Wall

By Rafael Soldi | Published October 7, 2020

Interview conducted August 2020

Strange Fire Collective is partnering with the High Wall to present interviews with the High Wall’s 2020 featured artists.

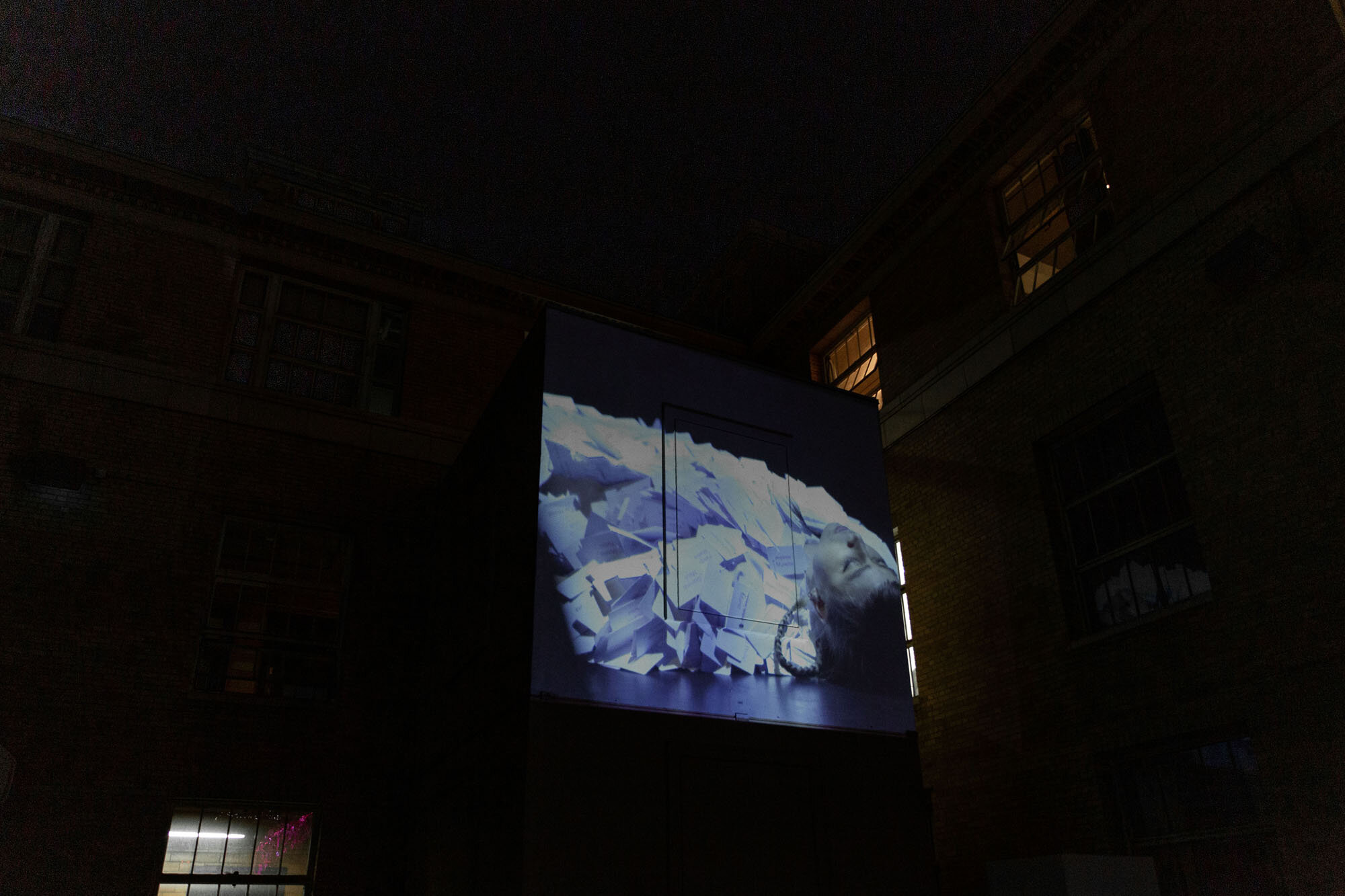

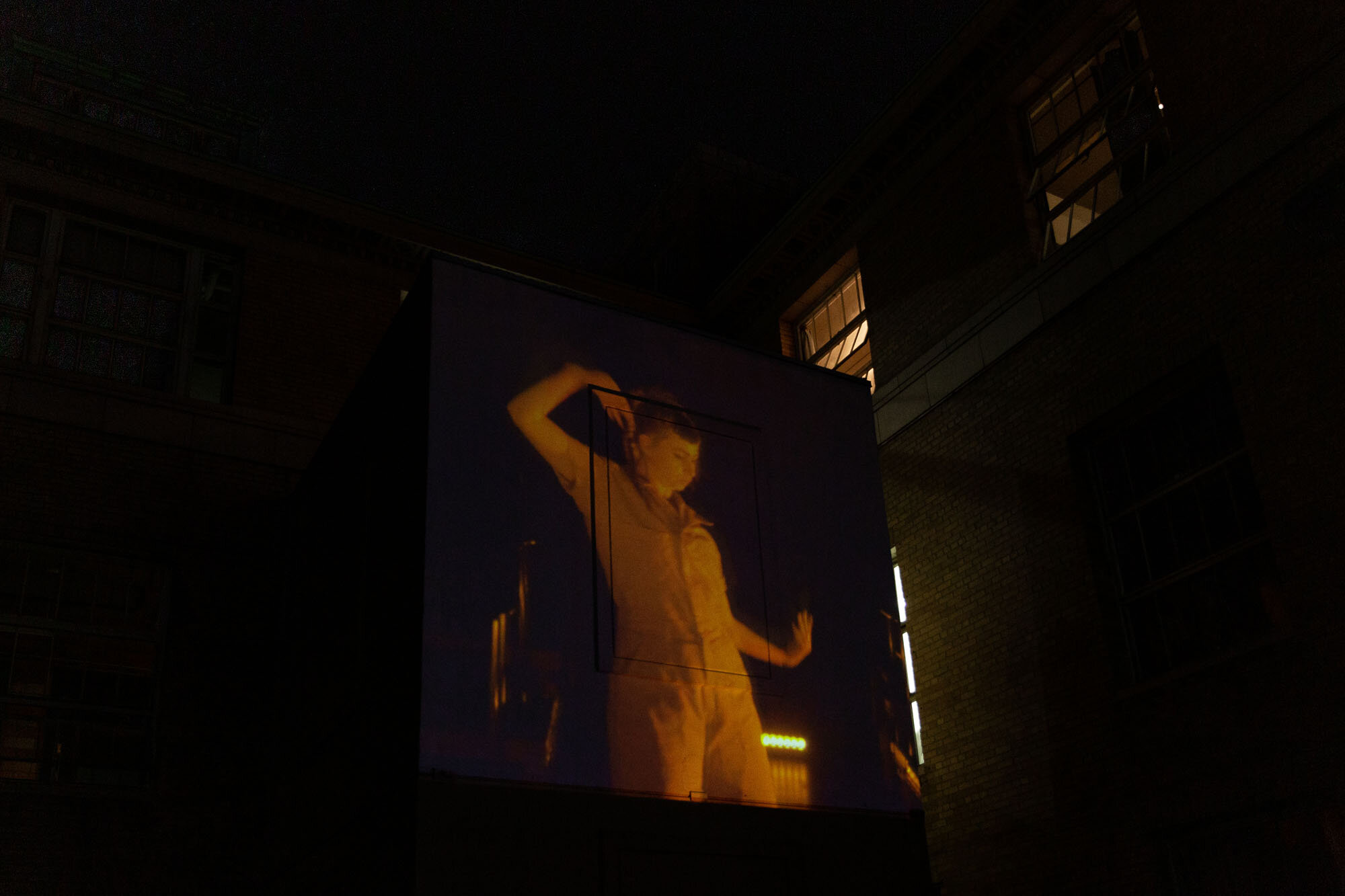

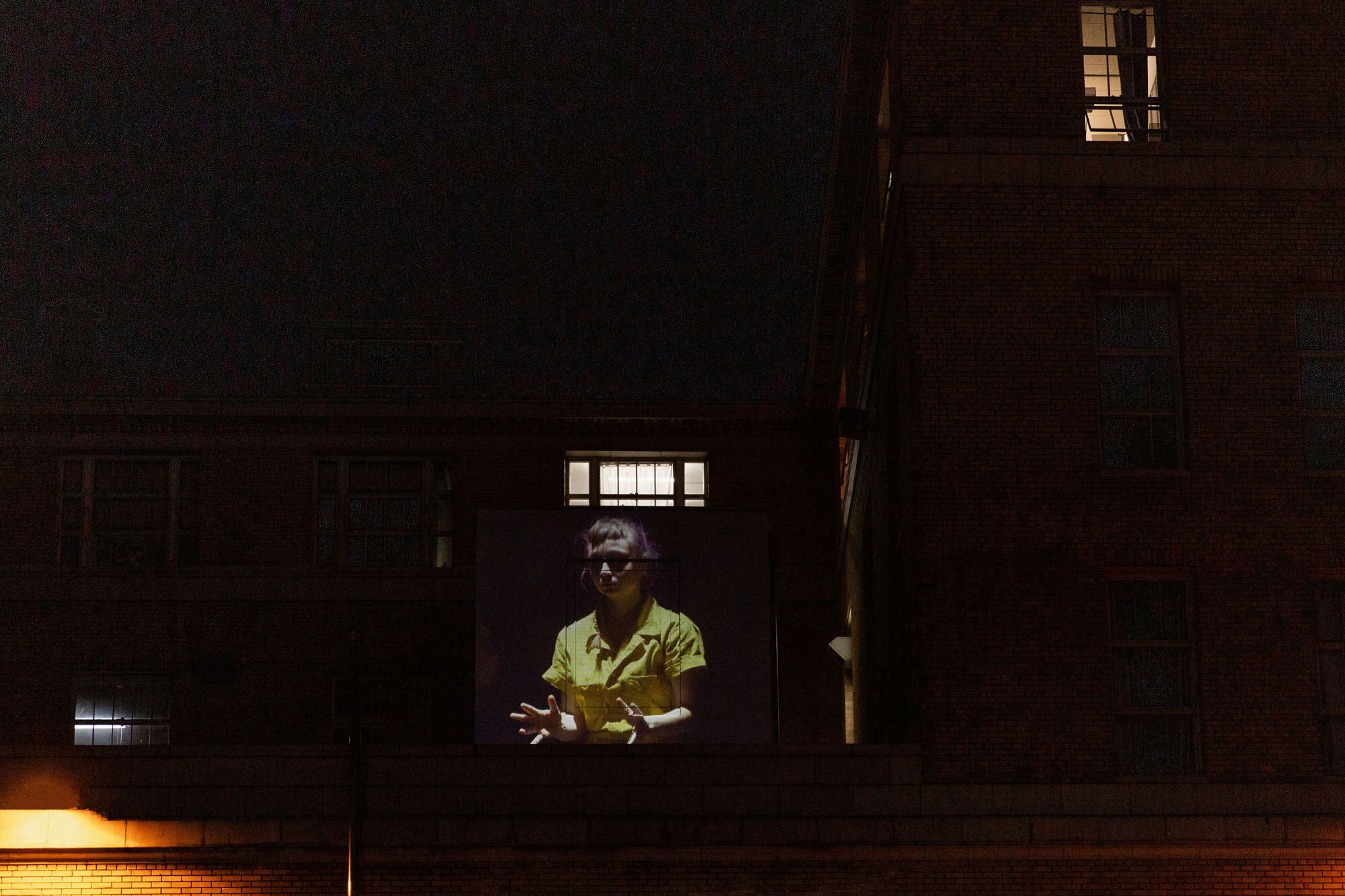

The High Wall is an outdoor video projection project at the Inscape Arts Building in Seattle, WA. Honoring the building’s complicated history as an immigration station, the High Wall aims to show the work of artists who are immigrants or working with themes of immigration, borderlands, and diaspora.

Every year the High Wall invites three artists to create an intervention on the building’s facade—a public video projection visible from multiple public spaces. The works were on view August 13-16, 2020. The High Wall is co-curated by Britta Johnson and Rafael Soldi; here we present three conversations between the curators and each artist/artist team:

Alice Gosti (below)

Nadia Ahmed

Gazelle Samizay & Labkhand Olfatmanesh

Alice Gosti (she/her) is an Italian-American immigrant choreographer, hybrid performance artist, curator, DJ, and architect of experiences. She is based out of occupied Duwamish and Coast Salish land, now named Seattle. Raised in a bi-cultural family of installation architects, her performances live and breathe the dualities within a multicultural environment. Alice works simultaneously with film, installation, wearable art, sound, poetry, digital platforms, and audience interaction to create durational performances integral to their non-traditional sites, to create cultural moments for audiences from one to 15,000.

Gosti’s work has been recognized with numerous awards and residencies. Gosti’s work has been commissioned and presented nationally and Internationally in universities, theaters, museums and galleries.

Rafael Soldi (RS): Hi Alice, thank you so much for taking the time to speak with us. We’re thrilled to be sharing this video on The High Wall. I had the privilege of seeing this performance live in 2019. I know that your process is very important to you;, how long did it take you to prepare for it?

Alice Gosti (AG) : I am a long-process kind of artist in general, but since this work was so personal it took even more time. Finding ways to share parts of my personal history without making it trivial, corny, childlike or narcissistic felt at moments like an impossible task. And I still wonder about the way I engaged. What kept me going were moments, conversations with other immigrants, when I would hear and see how necessary it is to create conversations around immigrant identities that are not focused on othering, exoticizing, and shaming who we are and the cultures we come from.

I really started working on it in the Fall of 2018 as part of a residency at the McColl Center for Art + Innovation. Those were the first moments in which I focused on research and played with how to translate and transmutate my research into movement ideas. But one might say that I have been working on this piece all my life; and that I will likely continue to work on it for the rest of my life.

RS: Why did you need to make this piece? Why is now the time to talk about home?

AG: (Graphic content warning): To be completely honest, I make art for myself first—to understand my relationship with the world. There is something I need to work on. Something I need to think about. There is a question stuck somewhere in between my body, my movement and my words. I just need to dig in there and keep asking questions. Never expecting answers, but always finding more questions. Then, at some point that question in my body starts colliding into what I am seeing in the world. The world seems to express a similar set of questions and needs as I do. At that point is when I start focusing my energies and intentions. That tends to be the beginning of a new project. In this case, I was inspired by TV shows like “Fresh Off the Boat” and Aziz Ansari’s “Master of None.” Both TV shows seemed to be able to represent the American immigrant identity in a way I had never seen before. The stories reflected nuanced realities and complexities, as well as the writer’s individual perspective, without trafficking in general stereotypes to tell the story of one family or person.

But the world was not only showing me TV shows with immigrants not made into awful clowns or specks of their cultures, the world was also giving us Trump with his ridiculous ideas on immigration. We see ICE raids and thousands of people approaching Italy via boat in search of a better life, often washing up dead on the shore. Populist politicians winning presidencies all across the globe, enacting inhumane immigration policies. Immigration is still a complex topic. White supremacy, capitalism, and racism are all still very much present and thriving.

I needed to talk about immigration now, I needed to surround myself with immigrant voices, now.

RS: The live performance is obviously a very different experience from this video excerpt. But there is an energy to this video as well that I enjoy. Performance art and dance in general have such a long and intimate history with video and photography because documentation is/can be so important. What do you think about this piece existing in these two ways? Are there things you feel you can better communicate with one versus the other?

AG: I love video art, music videos, installation and film. I agree with you, that the camera has a strong bond with dance and performance. Artists like Bill Viola, Maya Deren, and Matthew Barney have always been huge influences for me. In undergrad I studied experimental film at the University of Washington in the Digital Arts and Experimental Media Department (DXARTS). I started thinking about my choreography as film and film as choreography. Filming and learning to edit film taught me a lot about how I wanted the viewer’s eye to move inside of my work. But as you mentioned, documenting dance and performance is a powerful tool, but it is not the same as seeing the actual performance. When a new video is created with footage from the performance, as if it were found footage, a new choreography piece is being made. A piece that can stand on its own.

I am a fan of film documentation. I am able to understand and maybe experience or imagine what an experience of some of my favorite pieces of performance could have been if I had seen them live in person. I have come to understand much of performance art because it was filmed, photographed, and documented. But documentation is completely different from creating a new art piece with footage from a performance.

These two versions of this performance can communicate different things and connect to different people in separate ways. The video doesn’t need my body, it can travel wherever I cannot travel and continue the work that this project was set up to do through a different medium.

RS: Can you tell me about the garment you wear in your performance, with all the paper slips attached to it?

AG: My incredible dramaturg and co-writer and friend, Tim Smith-Stewart wrote this text about the dress. During the performance, I would start reading this text and speaking about the dress after I asked who in the audience was Italian:

“I anticipated the potential for this question to be asked and wanted to offer a clear and specific response. So I read this pre-written note.

This dress is composed of the names of 1935 Italian Americans who were either arrested, interned, or had their residence, property, or occupation restricted due to being designated by the US government as “enemy aliens” during WWII. This project has involved a wide spectrum of research into my personal history, Italian history and the history of persons of Italian descent in the United States. I did not learn about the history of internment in the U.S. during WWII until I moved here. As part of this research, I learned about the restrictions placed on certain persons of Italian descent in the United States, including the internment of 418 Italian Americans, during WWII. I typed each of their names on pieces of paper and attached them onto the dress.

I read their names and I think of the names of my friends, my family name.

Creating this dress was a process to combat erasure, and to create a physical connection between my own history and lineage to the Italian-Americans considered “enemy aliens” during WWII. The gesture is not meant to equate the treatment of Japanese Americans to Italian Americans during WWII. A much greater number of Japanese Americans were interned and their freedoms were stripped to a far greater degree. I want to highlight this distinction because I think it is important to recognize commonalities while not universalizing experiences, both historically and currently.

These Italian-Americans were unjustly deprived of their freedoms, displaced, and dehumanized. And it is also true that Italian-Americans by and large were not subjected to the same levels of mass internment as Japanese-Americans. It’s also important to say that Italian-Americans post WWII were largely accepted into the privileges of Whiteness in America. The process of constructing and wearing this dress is also a way of acknowledging the ways in which these complexities and dichotomies live in me and speak to my experience of someone who experiences othering and stereotyping, but who has also experienced considerable privilege as a White European immigrant in comparison to non-European fellow immigrants.

**I do not condone the Italian Fascists who participated in WWII, nor the Nazis who were being justly combated against.

My experience is my own. Again, I think it’s important to recognize commonalities while not attempting to universalize the experiences amongst all cultures and groups of people.

Lastly, this dress is a poetic action. I believe in the importance of poetic action. I also believe in the importance of direct action. The rights of all immigrants in this country are under attack. Those who are most affected are non-European immigrants. Families from mostly South and Central America are being torn apart, children are being detained in cages and many immigrants from majority Muslim countries are being denied entry to the United States. ICE raids and deportations have become and are becoming more frequent. In the spirit of direct action, I would like to highlight two local organizations who could use our support:

Northwest Immigrant Rights Project

Washington Immigrant Support Network

Donate if you can. But there are also other ways you can get involved, including deportation defense and rapid response volunteering. I encourage you to read about these organizations and many others and take action when and where you are able.” – Tim Smith-Stewart

RS: Tell me about the language you created for this piece. There are repeated gestures, like the tapping on your face, or the pounding on your chest, and other articulations. How did these come about?

AG: The gestures that you are mentioning are part of one specific section of the piece, created by stringing together culturally specific Italian gestures. Italian culture, just like many cultures, gesticulates a lot. Each gesture has a meaning. While working on this project I came across Bruno Munari’s book Speak Italian: The Fine Art of the Gesture. This book inspired me to string together a series of Italian gestures and gestures from my life and treat them as I usually treat movement and choreography. Tapping the head is a gesture connected to thinking. Tapping the heart is a personal gesture. It is something I have always done to find comfort when I feel hurt and sad. Literally, when my heart hurts I find myself tapping my heart. My body knows what it needs.

I love repetition, those gestures are repeated for a long time. Longer than one usually sees movement performed. The intention is through repetition to subconsciously move the focus of the audience from the movement, to the sound that the tapping makes, to what the gesture might feel like in extensive repetition, and come back to the bodies in the room and the movement happening. What I love about repetition is the capacity that it has to move focus. Zooming in and out, from movement, to feelings, to sensation, to returning to one’s own body.

I work with movement as meaning making, as storytelling. Movement is poetry. While I, as the maker and performer, have in mind a very clear meaning and sometimes narrative, it is also necessary to create systems that make space for multiple meanings. I am not of the school in which we have to tell the world how to feel, what to see, and how to understand it, otherwise I failed or they failed. I am of the school that clarity can still exist inside of the artist even while creating the potential for multiple meanings. Most of the time if the artist is clear, those meanings can align.

RS: This piece is a deep dive into your Italian-American identity. You literally ask in the title, “Where is home?” Almost immediately after completing this piece, you found yourself in Italy longer than you expected due to COVID-19. Have any of the journeys you went through in preparing for this performance surfaced during this unexpected, extended stay?

AG: The biggest thing I keep coming back to is the importance of validating the experiences I had when I was a young person, in relation to my immigrant identity. Some of the things that happened to me, some of the things that still happen to me, I don’t have to make them OK, if they hurt me and make me feel isolated and deeply alone. I don’t have to make you feel OK, because you are making racist remarks that hurt me. For most of my life, I did not validate my feelings around feeling othered or exoticized. I would get mad and angry and not know why, and I would feel like I was in the wrong, because people were just being funny, or ignorant, but they were not consciously trying to hurt me. Being here, in Perugia, Italy, in this time, for this extended amount of time has really given me a chance to revisit some of the memories, some of the provocations, aggressions, and microaggressions that I have experienced and experience daily in both worlds. I say to myself, you have all the right to feel hurt, angry, frustrated, those ARE racist comments. This extended stay has given me the chance to use the tools I learned from the work, to remember all the incredible humans who identify as immigrants who have shared with me similar stories, and hope that there is a young human out there who can find validation for their experience and the complexity of their identity sooner than I did. They are not the problem. They are not made wrong.

That is why a big part of this project is working directly with immigrant communities, creating more bridges and moments of connections, breaking the systems of oppression that continue to label and shame immigrants all over the world.

Good news, I have been selected as a finalist to create a new chapter of this solo to present and work on here in Italy. I have always seen “Where is home - birds of passage” as a chapter in the “Where is home” saga. In that chapter I was talking to people in the United States. The new chapter, “Where is home - la straniera,” will be created as a conversation between Italian people and I. I will continue to use both languages, but what I imagine speaking to each one of these worlds is very different.

RS: This project required a lot of collaboration, even though it’s an autobiographical one-woman show. Is collaborating with so many other creatives just a necessary evil for your projects, or do you feel it contributes and shapes how a project comes to life?

AG: Collaboration absolutely contributes and shapes how the project comes to life. Even most one-person shows are never really a one-person show. For example, unless you can activate the sounds and the lights on your own from the stage I would debate that you are still collaborating with other people.

I have also been wondering about the idea of, are we ever alone in creating? Is the solitary genius that works in a vacuum really something concrete? Or is it another product of Western colonial capitalism?

I think it would be really interesting to start shifting that mentality, or debate it and question it. My parents work together under one name, SANDFORD&GOSTI. I was recently having a conversation with my babbo about artistic couples. What makes an artistic couple? Partners (Gilbert & George)? Brothers (The Brothers Quay)? Alter egos (Alighiero e Boetti)?

As we were talking I started wondering about all the artists that had invisible or hidden collaborators (Picasso, Rodin, Claude Cahun).

Then my brain jumped to the question: How can we exclude or include the support of our communities in the way we speak about authorship? I am and will always be the author of the things that I make, but is there a way to acknowledge community, family, ancestors as much as we credit the sponsors? Both are necessary and undoubtedly part of the support system that fosters the creation and enables the creation.

I love collaborating. It is one of my favorite things in the world. Honestly, I do not like being in a studio alone. I would have never performed in this show myself if I did not feel like it was too autobiographical to have somebody else perform it. I love being in a room with other people. Ask them questions. Get them to ask me questions. Play. Discover. I am so much more interested in being in relation with others. People inspire me.

Britta Johnson (BJ): There are a few moments when the camera reveals streaming text—in Italian, also in English. Can you talk about the text elements, how they connect with the piece?

AG: As a bilingual person, I have always felt like my writing and word-smith was/is inadequate: both in Italian and in English. My language, my accent, my choice in words and sentence structure has always felt like an opportunity for people to comment on it, exoticize me, or tell me how cute I am, how charming I am; and in this way remind me that I don’t belong. When you are constantly being othered, sometimes you really wish you could just be invisible. I am White, I know that if I don’t speak I benefit from the privilege of being invisible in most countries. That was never true in Italy (my home country). As a consequence, I never felt like my language was ever strong enough to be part of my art.

A huge part of my creative process is writing. Writing. Writing. Writing. All the time. And the more I worked on this project the more I felt like I needed to use words. Some of the memories I was revisiting needed words. Needed to be told out loud, and understood in the most direct way. I owed it to those memories, to those versions of me. I owed it to myself to let those words be in whatever language they existed in, letting the audience wonder in multiple languages and not default to English. Stop the process of erasure and defaulting to colonialist practices that want us to always speak in English.

I am so thankful to the encouragement of my dramaturg and co-writer Tim Smith-Stewart for encouraging me to write, and encouraging me to share the writing and the words of the piece with the world. I appreciate him hearing my experiences and fears but also validating the artistry of the text and the memories I was interested in sharing.

BJ: Thanks so much, Alice, for sharing your thoughts about this beautiful piece!