Q&A: Annabel daou

By Rafael Soldi | November 24, 2016

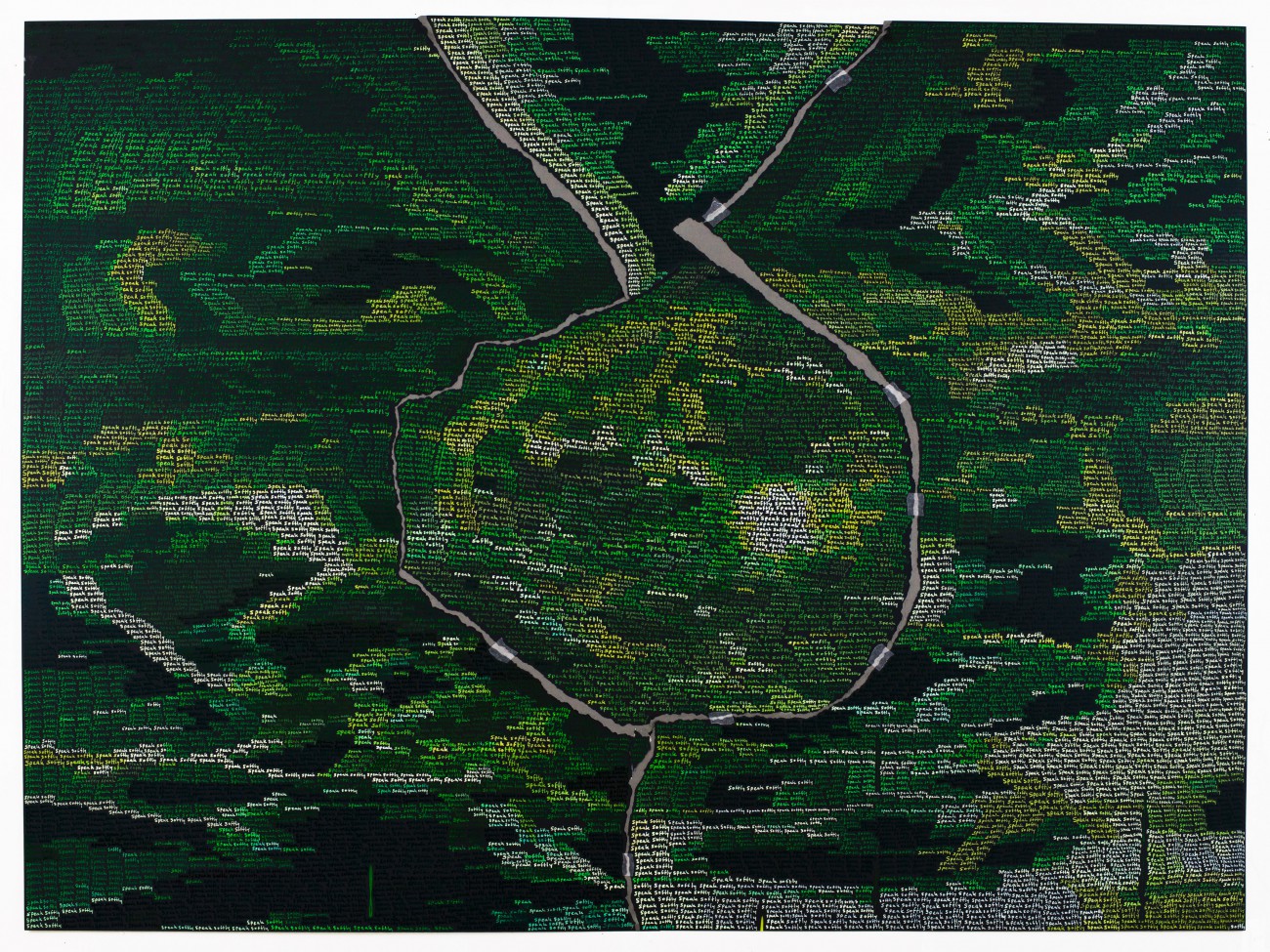

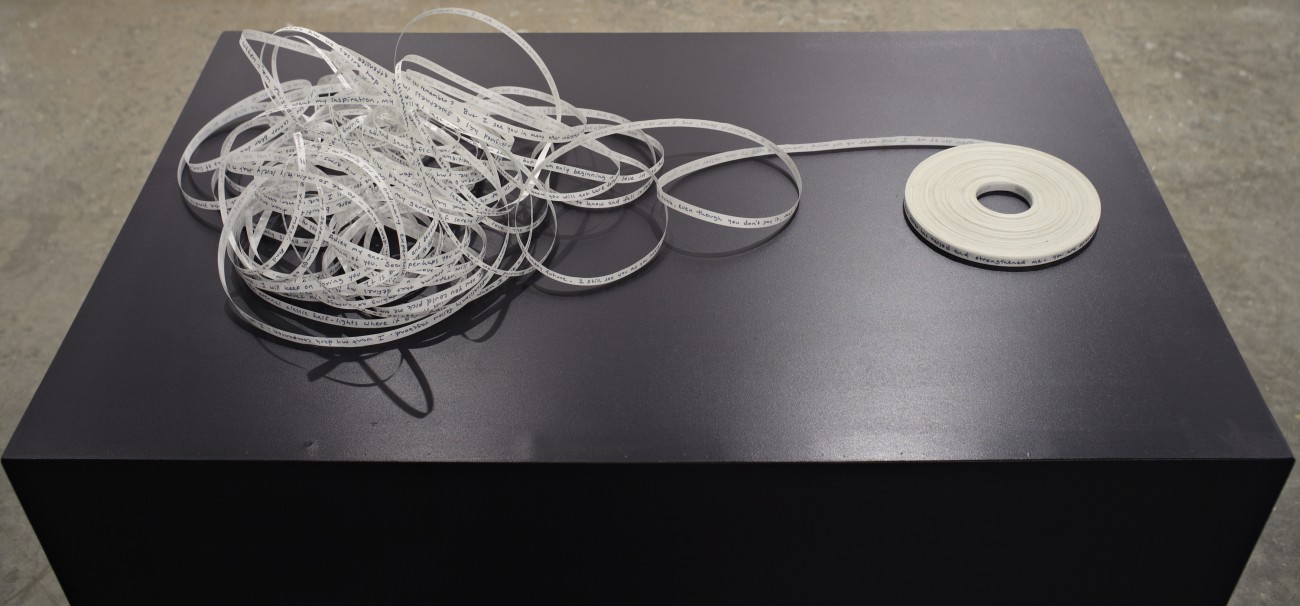

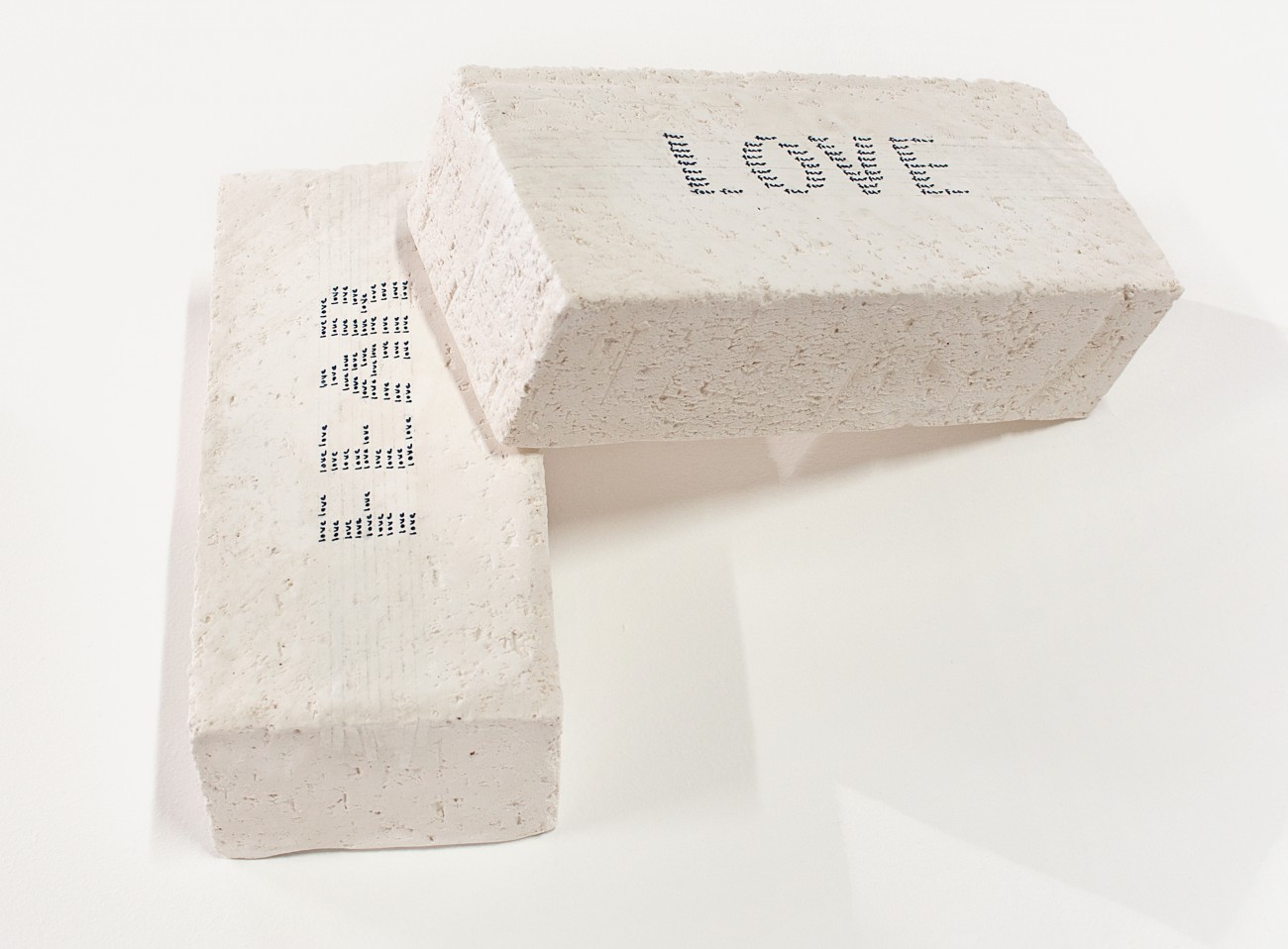

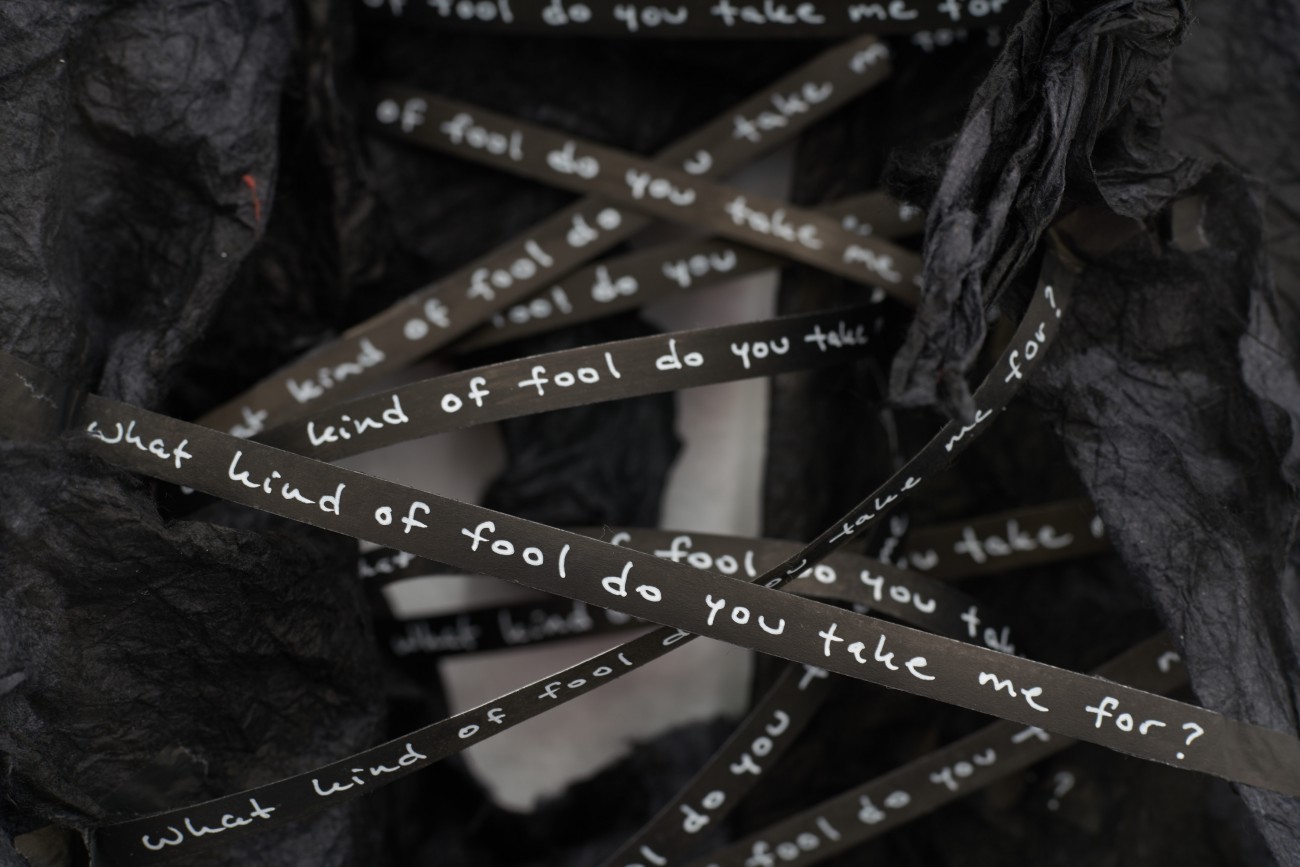

Annabel Daou’s work occurs at the intersection of writing, speech, and non-verbal modes of communication. Her plastic/paper and tape-based constructions, sound pieces, and performances explore the language of power, intimacy, and self-encounter. Daou reconfigures the surfaces of her works through processes of destruction and repair. Mending tape transcribed with language alternately holds together and pulls apart the various materials. The phrases in Daou's work are drawn from personal, literary, and historical sources. She uses repetition and subtle shifts in the iteration of idioms and ordinary speech as a means for investigating shared experience and misunderstanding.

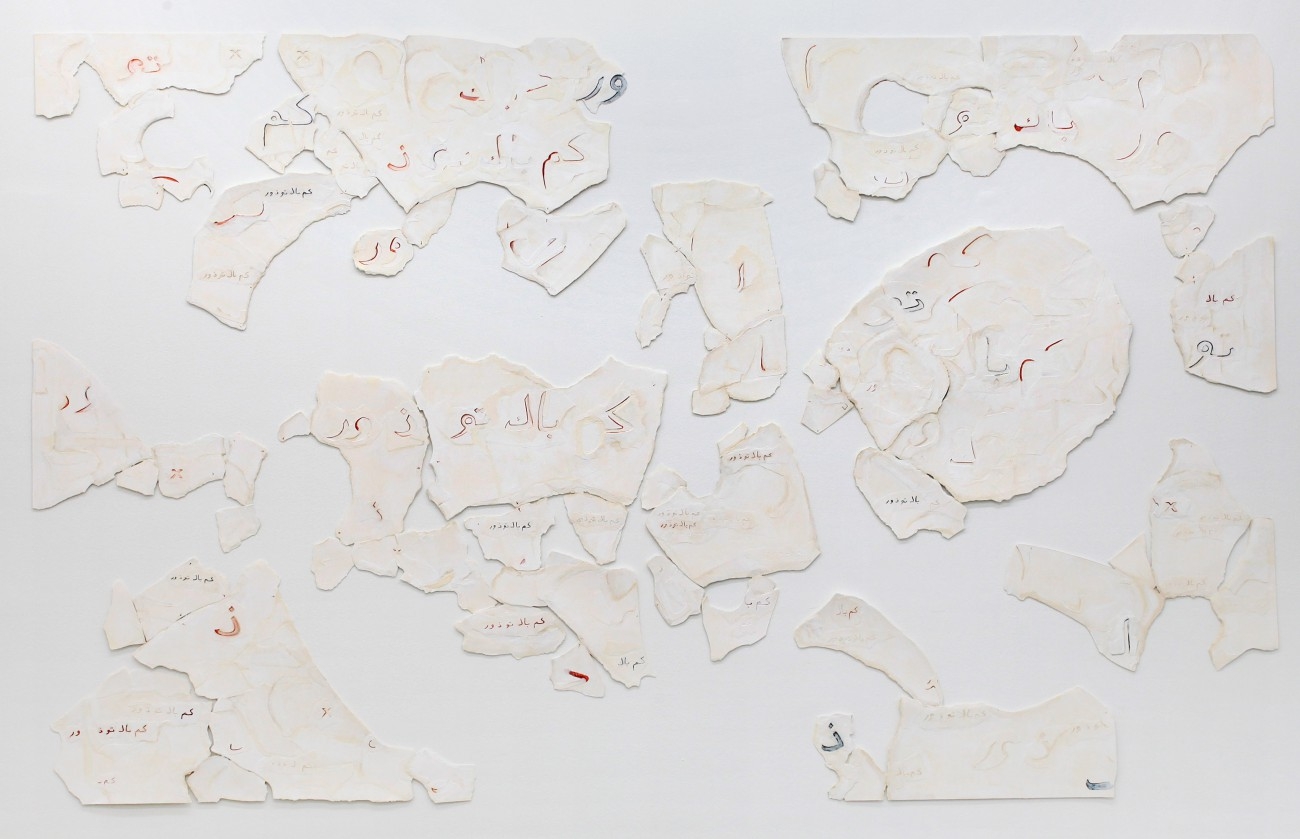

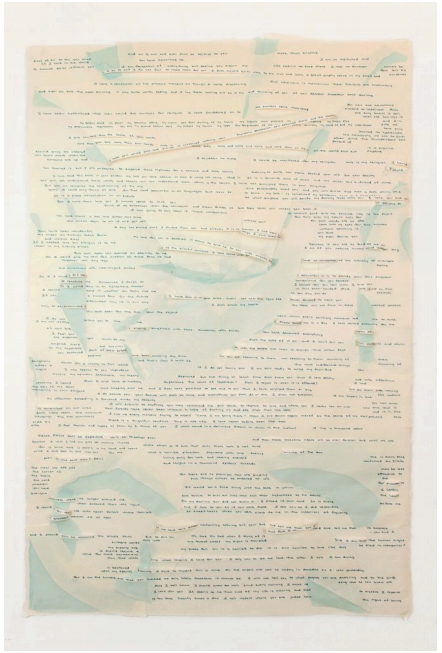

come back to the war, 2011

Rafael Soldi: How did language find its way into your work? Why do you identify as a language artist and not a text-based artist?

Annabel Daou: I used to be a painter. When the US went to war in Iraq in 2003, I made my last paintings and threw my paints away. I think it was a direct response to feeling speechless in the face of the completely illogical insanity of that moment and the sense that everything that was being said meant nothing—or more to the point, that there was a willful misuse of language. I think I felt that I wanted to make a gesture that was meaningful, at least to me; that was an acknowledgement of how consequential the aggression felt. Standing in my empty studio, I was faced with a blank page so to speak and for some reason my first inclination was to regain language—to find the words.

I was always a little uncomfortable with the materiality of artwork, its body and boundaries were something I struggled with. For me it was the expanse of language and its capacity to be limitless in some way that felt to me to be a kind of space of freedom. It’s not the form of text/words themselves that I’m drawn to but more the communication/miscommunication that language, written, spoken, and obstructed, allows for. Funnily enough I always disliked my own handwriting and the fact that it has become my act of making is always slightly amusing and discomfiting to me.

RS: Talk to me about this idea of pushing against our identity, of rejecting self-tribalism.

AD: It would be disingenuous to imagine that we can wholly escape the confines of identity when we are so often faced with other people identifying and reacting to us, often in aggressive and humiliating ways. When I talk about pushing against identity I’m expressing my inclination to try to question how responsible I am for allowing my own self-identifications to cloud my capacity to be open to others and their experiences of the world. With respect to my work, I always want to question whether I’m exploiting elements of my story and in some way perpetuating the very concepts that my work is questioning. Having grown up in the midst of religious and ethnic conflict, I’m wary of any over-attachment to group identification—but then perhaps even my dis-identification once again ties me to my personal history. It’s a paradox. In the end I’m simply more interested in finding different ways of communicating than I am in how we differ from one another.

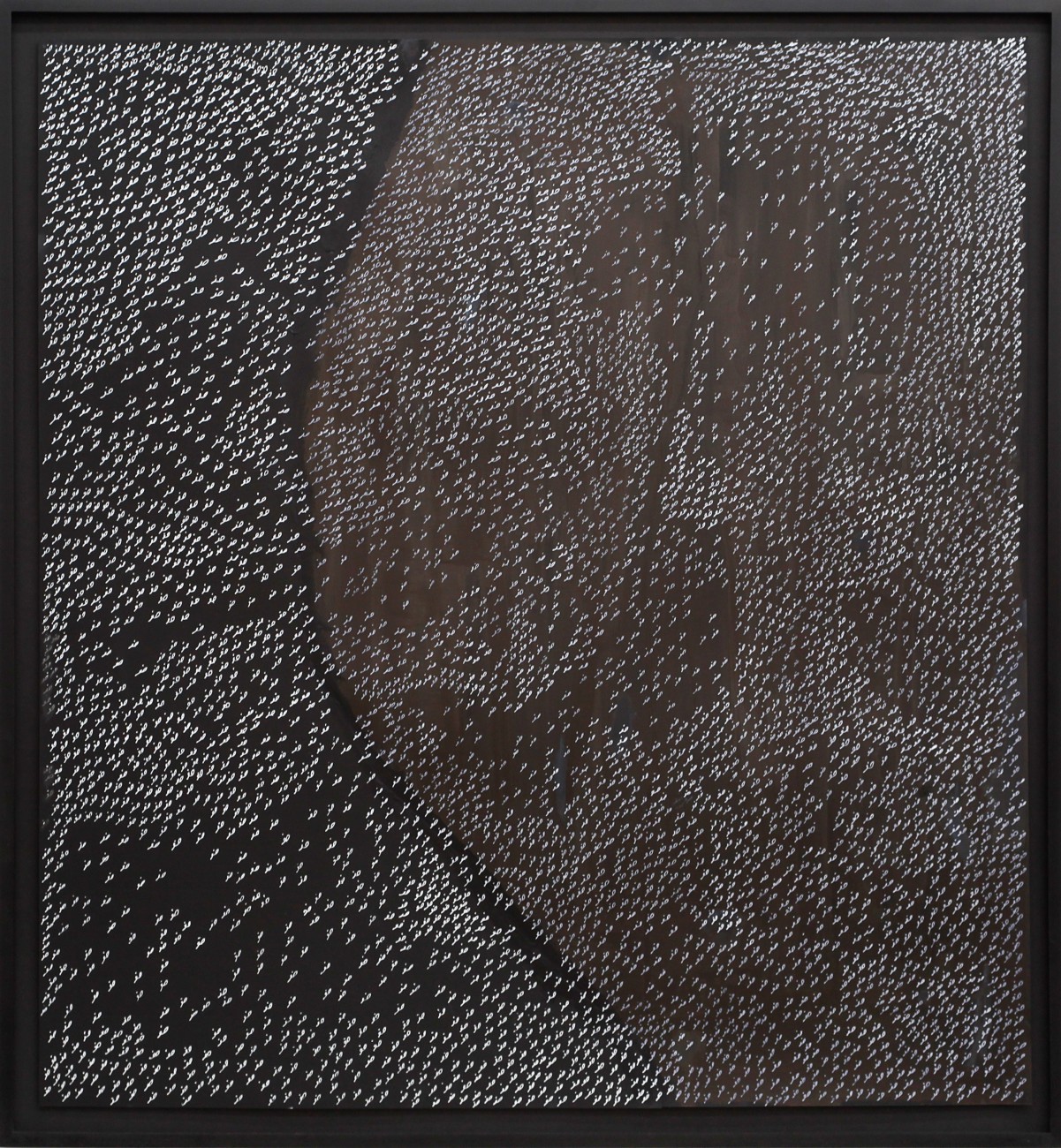

your secret is safe, 2014

RS: So much of your process is about building and tearing down and rebuilding, about mending. Is this process reflective of your relationship to the world around you, or is it purely formal? What role does language play in the mending stage of your process?

AD: It’s odd because I feel very attached to the process of mending, but I’m not a very careful mender and my repairs, more often than not, are the result of makeshift, often awkward and repeated efforts, and so they are usually quite evident. I have often questioned myself as to whether it’s laziness that leads me to resolve things in the most haphazard and circuitous way, but I’ve come to realize that I find meaning in the process of tearing and repairing and allowing for that process to be part of what remains visible in the work. I’m not too precious about objects in general. I’m more interested in rattling what seems too stable or whole. I don’t quite trust anything that isn’t at least a little broken. For me life is a constant cycle of picking up the small pieces and pulling things together knowing that there’s always a risk that it will fall apart again.

I think language can be the ultimate means of repair in that it allows us to communicate or in some cases miscommunicate in a generative way with one another. Language for me, with respect to the work, is both the invitation to understand and the rejection of the possibility of a total and stagnant understanding of the work or of the self as a whole, since we can never “read” the entire work at once. Language is contingent on time and place and so I feel that my work is always opening and closing itself to understanding.

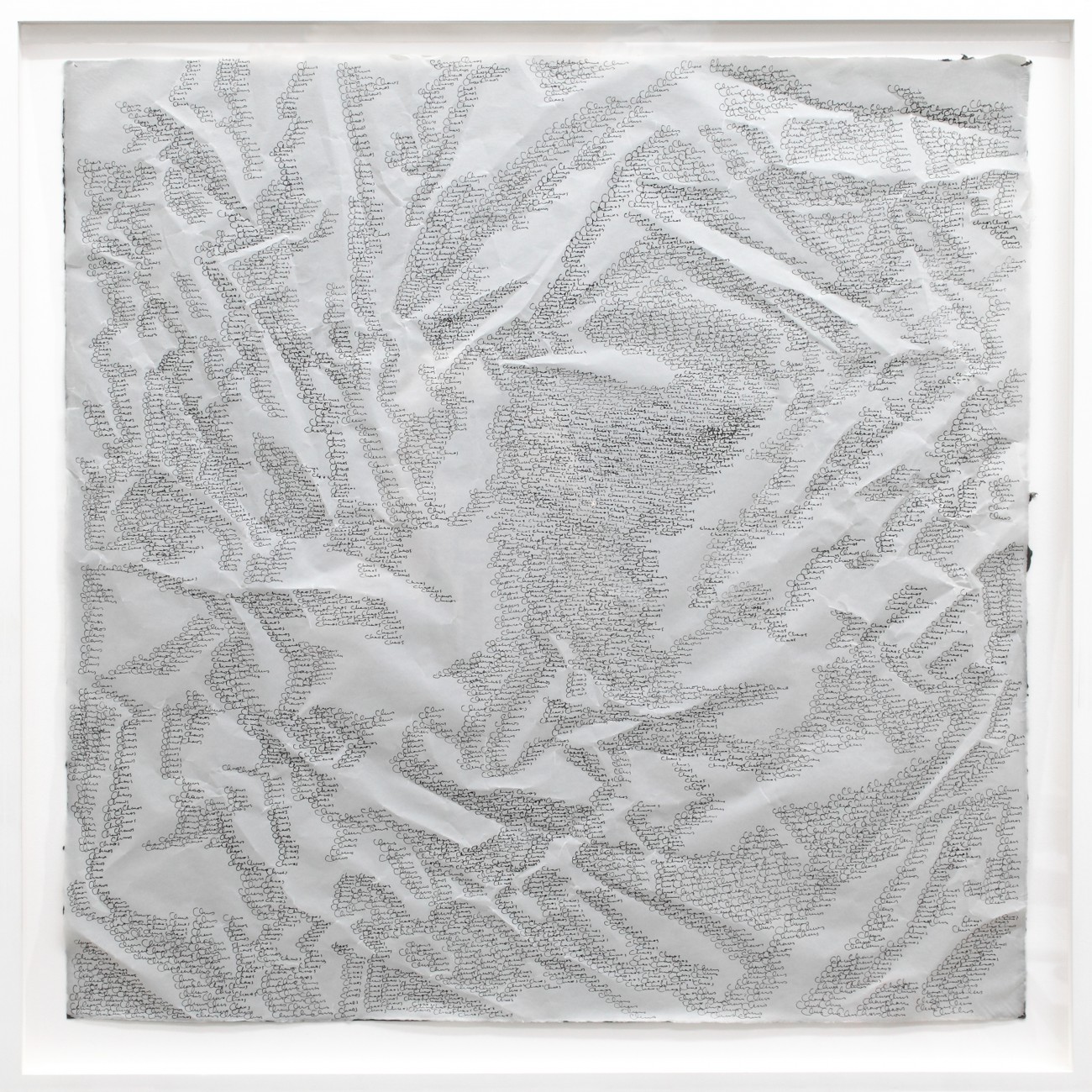

i don't care about your body, installation view at Galerie Tanja Wagner, Berlin, 2016

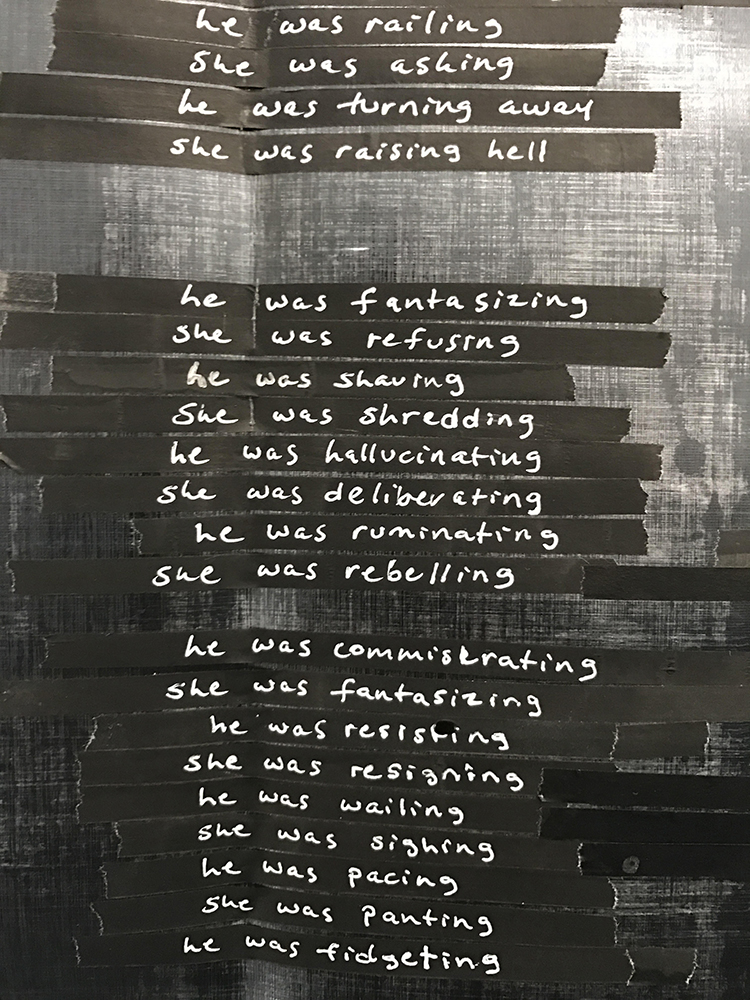

they were here, 2016

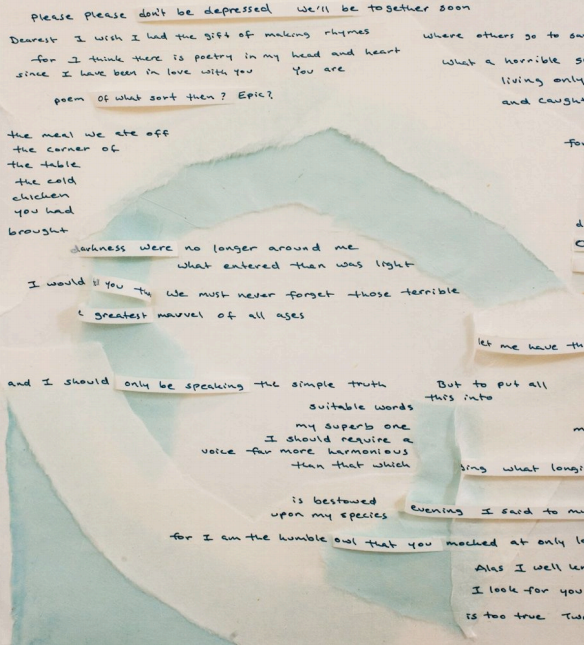

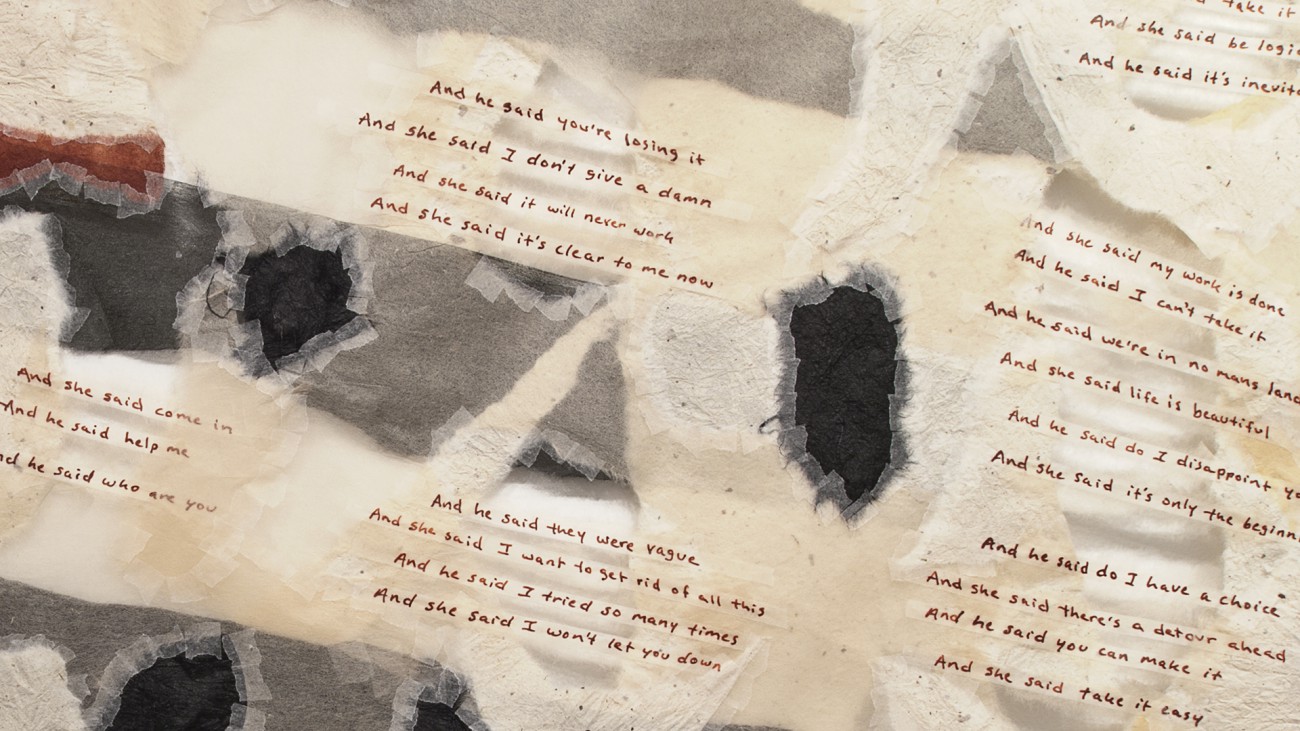

RS: I saw your beautiful show at the Tanja Wagner gallery in Berlin and was really taken by your large piece, they were here. In it we see a fragmented narrative of two people living their lives, a vast collection of "He" and "She" statements; two people staying and going. You described this piece as a city in ruins—so strong yet so fragile, a transient city where every narrative is interesting and uninteresting. Can you talk more about this and the themes that run through your show?

AD: they were here is the central piece in the show, which was titled I don’t care about your body. It’s like the little carving on a tree or on a school desk, so-and-so was here. I was thinking about narratives of lives over time and how they intermingle and repeat. I wanted to build a city that was both present and in the aftermath of its existence. I grew up and have lived in old cities for most of my life and I’ve always felt that cities are built of the echoes of the things that people have done in them, the acts of living, of thinking, of feeling, are the actual building blocks of a place.

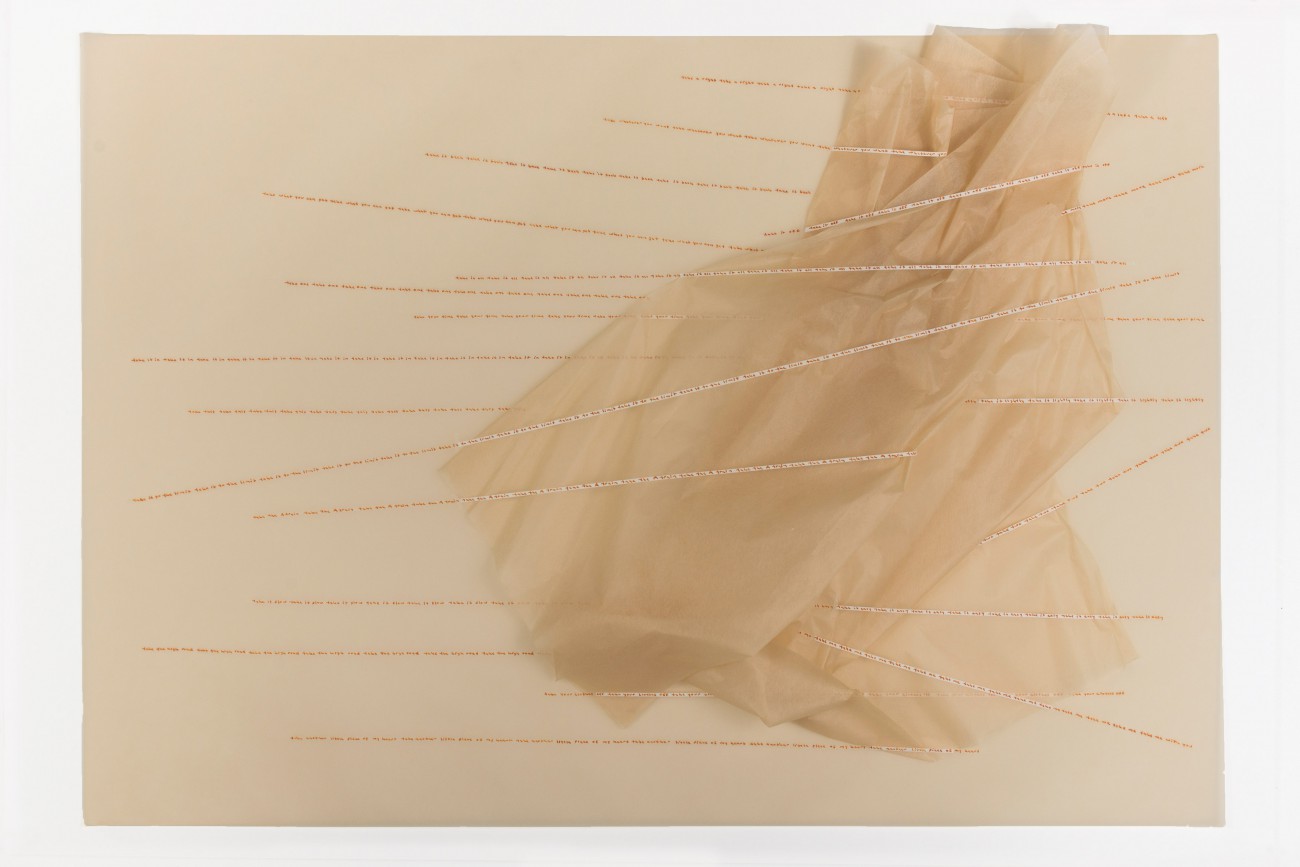

This piece is made out of very lightweight material called cuben fiber—it’s used to make tents and sails. I wanted the city to have weight and be weightless, to be rising up and swinging on all kinds of perspectival axes and also to be melting, falling, exploding into shards. The piece is held together and reinforced with repair tape on which I hand wrote hundreds of sentences each describing an act, either physical or emotional or metaphorical, that “he” and “she” were doing. The sentences are always in the past tense. While they could denote that an action was taking place at some unspecified point in time, they can also be read as a description of what someone was doing when something significant happened--like Pompeii where people were in the process of doing something when the volcanic ash froze them in the act. The sentences at times are figures of speech—something I very often make use of: ”he was losing his mind,” “she was taking it in,” “he was calling it quits,” “she was giving up the ghost,” “he was wasting away,” “she was standing her ground.”

This piece was the beginning of the show and the title of the show itself is probably due in some sense to the piece. I wanted to privilege the act over the specific bodies as I tried to indicate this abstract city, the “place” where people have lived and died and wept and taken up arms and laid down their weapons and fallen in love. The show in some ways is about the fact that there are consequences to each act no matter how inconsequential they may seem--that we construct our reality through our acts.

they were here, 2016 (Detail)

I was also thinking about the work of art as a body, and the ways in which we engage with its boundaries. Another piece in the show, titled rules of engagement, is made of ripped up papers forming three intersecting circles/bodies, held in place by strands of repair tape. Each strand repeats a phrase that indicates engagement or disengagement with another body: “touch me,” “don’t touch me,” “look at me,” “don’t look at me,” “stop me,” “don’t stop me,” etc…

Positioned between these two works in the gallery there was a sculpture: my clasped hands and forearms cast in salt. It’s called someone who might have been there. I wanted the visitor to enter the space and be confronted by the folded hands of the inquisitor/interrogator or, in another sense, the one who is waiting, expecting, not acting in any physical way—post action, frozen. The sculpture is set on a mound of loose salt and among other things, could be taken as a reference to the moment that Lot’s wife looks back at the burning cities behind her and turns to salt. Given that the show approaches and then tries to disentangle itself from any specific narrative, I was interested in the gesture of looking back—an act that historically, in art, religion, and mythology has had dire consequences.

RS: As an artist telling your story through your work, how do you find balance between telling your story and elevating trauma?

AD: The inclination to make work can be born out of a need to understand or work through trauma, both personal and societal, but my feeling is that it’s not so necessary to reveal the origin or story behind that trauma in the work. In fact for me the work is hindered by too straightforward an approach to narrative. It has to be free to exist in its own dimension, slightly outside the personal. But there may be something contradictory in what I’m saying. Perhaps I’m in some sense elevating the trauma by saying that it shouldn’t be confessed in the work. Because the implication could be that we need to keep our trauma close to protect it from being diluted. In any case, in my work I’m always interested in breaking down what seems too clear, in keeping things just a little hidden, allowing for the work to hold its own secrets. My last show at Tanja Wagner was called “your secret is safe with me.”

RS: Tell us about the long term project you've been working on and what's next for you.

AD: Since November 2007 I’ve been trying to write a book. It’s called autobiography of a, and the first line is: “I’m walking backwards, for 120 days I would begin writing the story of my life…” It’s approaching ten years and I’m now turning the “book” into a video project that will consist of 120 episodes each focusing solely on my hands while I narrate the different episodes. The episodes collectively enact a search for the presence of the artist as well as a search for the witness to the artist’s evolution. They deal to a large extent with who the storyteller is with respect to the story and whether anyone can ever really tell their own story.

In the show at Tanja Wagner I exhibited the first six episodes of this project. There’s still some writing to be done and of course the filming of the remaining episodes, so I’m going to sink myself into this for the next six months. I plan to work with different directors and filmmakers on some episodes. The project has been accompanying me for a while now, but I’ve never given it my full attention, so I’m not certain of what it will feel like to do that. I’ve given it the boundary of spanning a ten year period and so I plan to have it completed by fall of 2017.

Another project I’m thinking about relates to a piece I just took down from a show called Acts of Sedition in New York. It was something I made around the time of Occupy where I walked through the city streets and stopped strangers to ask them, which side are you on? In the vein of this piece I’m planning another work that will have something to do with the voice in the street and with sharing our voices with each other. I would like to ask people to speak the words of someone else. One of the points of departure is a line from a story by Plutarch that Mladen Dolar talks about in one of his books. It has been in the back of my mind ever since I came upon it. Plutarch tells the story of a man who plucked a nightingale and finding but little to eat exclaimed: "’You are just a voice and nothing more.’”

All images © Annabel Daou