Q&A: Birthe Piontek

By Rafael Soldi | Published on June 8, 2017

Originally from Germany, Birthe Piontek moved to Canada in 2005 after receiving her MFA from the University of Essen in Communication Design and Photography.

Birthe describes her art practice as an exploration of the individual while being especially interested in questions around memory, the subconscious, as well as the topic of female identity and its representation in our society. Her main focus is photography but she also utilizes other art forms like installation, assemblage and collage to investigate to what degree our complex identities can be visualized.

Her work has been exhibited internationally, in both solo and group shows, and is featured in many private and public collections such as the Museum of Contemporary Photography in Chicago and the Museum of Applied Arts in Gera, Germany.

Birthe's project The Idea of North won the Critical Mass Book Award 2009, and was published as a monograph in 2011. She was nominated for the AIMIA AGO Award 2014, and her project Lying Still was shortlisted for the Edward Burtinsky Grant in 2016.

Her work has appeared in a number of international publications like The New York Times Magazine, Le Monde, Wired and The New Yorker among others.

Birthe is a member of the Piece of Cake Project.

Rafael Soldi: I loved seeing your latest exhibition, Miss Solitude, in person—it's wonderful! Can you tell us a little about about this work and how those ideas have carried from Lying Still?

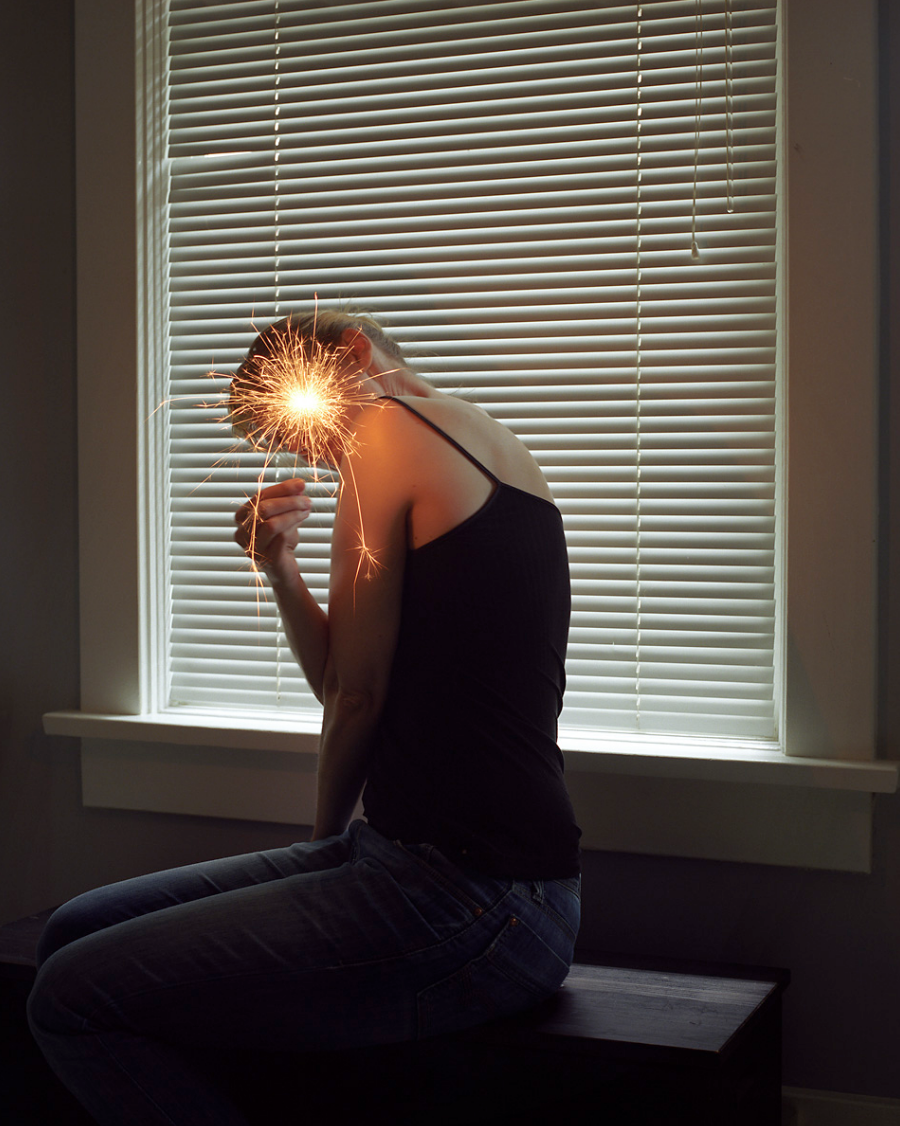

Birthe Piontek: Lying Still brought together self portraiture, still lifes and found vintage photographs in order to create a multifaceted dialogue around the expression of the self, the representation of women, and the female body.

Miss Solitude continues with the exploration of those ideas, but with less emphasis on the self. I’m using found images again, as well as assemblage of objects to look into both the fabrication and disavowal of femininity, beauty, memory, and desire.

Both projects revolve around the idea of the tension between the visible surface and the invisible underneath, the underside. This is definitely a recurrent theme in my work and feels like something I’m always coming back to, even if the visual language shifts.

Also, both projects include found vintage photographs as I’m intrigued by how these images, that were originally shot in a different context, can take on a new role and are transformed in their meaning by curating them into my work.

Miss Solitude at Access Gallery

RS: Moving from photography to sculpture and installation seems very fitting to me, in your case. How did this happen? How do you feel about it?

BP: In all my projects, I’ve have always worked with objects, mostly in the form of still lifes. I love the poetic qualities of an object, how it can be charged with meaning and interpretation, how it can act as a “stand-in”, and an expression of an emotion. Over time and especially when working on Mimesis and Lying Still, I found myself questioning my process. Why was the final result photographs of objects and arrangements rather than the sculptural objects themselves? Was I taking the image because it best expressed my ideas, or was it just a comfortable approach that I didn’t know how to leave.

Suddenly, blurring the boundaries between installation and still life—and the question of where does one start, where does the other end—began to fascinate me. I felt is was very rewarding and necessary to investigate the relationship of the two. I think that is what then resulted in the project Miss Solitude. For the first time I would not go down the familiar still life path but decided to walk into the other direction: working with objects in space and not an image of them.

All this feels very good and exciting to me, it feels quite natural and familiar. This has been evolving slowly over time and has been a part of me and my process for a while now—it was just a matter of timing and finding the right project for me to allow myself to explore it.

Miss Solitude at Access Gallery

RS: In recent bodies of work you play with aspects of beauty and terror, like a life jacket bedazzled in rhinestones, or emergency whistles silenced by wistful locks of hair in Miss Solitude. This strategy is also present in Lying Still, if you read between the lines. Can you talk more about this?

BP: As already mentioned briefly, I’m interested in the push and pull between the visible and the invisible. The tension between reality and dream, conscious and subconscious and also beauty and terror. We’re always surrounded by both and constantly have to navigate both as one can not exist without the other.

I’m interested in the question, how do we as humans cope with the knowledge that the beauty of being alive comes with the “price” of suffering? I compare it in my own life to “walking on thin ice”—you never know when it will break and you’ll fall through. I find it is incredibly difficult to hold this knowledge, to hold both: beauty and terror in equal parts and live within this tension.

Much of the work I’m doing lives in this grey zone. The images in Lying Still address themes of intimacy and mortality evoking the desires, urges and fears that exist latently in our subconscious. They refer to our dreams, to something unknown, an inner landscape of our minds that is hard to point out and put the finger on but that is yet so present and rules our being. The images are an expression or an attempt to invite the terror in, sit with it, and by giving it a stage, maybe even befriending it.

Miss Solitude addresses a bit of a different terror: the one that comes with the construction of feminine beauty and female identity, the one that is part of pageant or beauty queen contests, of needing to look or to be a certain way, or being labeled, measured and judged – mostly for appearance. It looks at the tension between an image that was created by society and the reality of what is left when you decipher or expose these familiar codes of constructed femininity.

From Miss Solitude

Miss Solitude at Access Gallery

RS: Recently you've turned to found vintage photos as source and reference material. These are often representations of women, femininity, and beauty from mid-20th century. What about these intrigued you? Why not contemporary images?

BP: Miss Solitude explores the construction of the mid-20th century, Euro-American ideal of beauty and female identity. Although I didn’t grow up in these times (50’s and 60’s), the created image of how women needed to look and to be was so profound that we can still feel the aftermath of it. And just to clarify it’s not just ideals of beauty, but more the whole image and role of a woman in society. There is a continuity, a relevance and the feeling of connection. Even though I’m living in different times, I’m shaped by it and am still carrying it in me. I think it’s the legacy of these images that I’m interested in.

Also, deciphering codes or deconstructing an image is probably easier if there is bit more distance, if you’re more removed from it. It’s more difficult to get a good impression of something if you’re standing too close. I guess it’s like that saying “ You can’t see the forest for the trees”. Using contemporary material for my work would be a lot more challenging as I’m, as a product of my time, so much more immersed in it.

Miss Solitude at Access Gallery

RS: In Kimberly Phillips' wonderful essay that accompanies Miss Solitude she points out the uncanny as a paramount element in your work. She goes on to describe the uncanny as something once comfortable and familiar that "becomes unrecognizable and thus deeply unsettling." Do you consider the uncanny in your practice? Does working with such an abstract concept make it easier or harder to explore the themes you're interested in?

JW: Yes, I definitely consider the uncanny a big part of my practice. I think it’s one of the common themes that you can find in all my work. It comes from the interest in that tension between dream / reality, visible / invisible, conscious / subconscious, and beauty / terror, that I talked about earlier.

For me it’s not so much an abstract concept as it is more a natural way of how my work wants to be. I don’t even think I could avoid it or make it look any different.

Maybe it’s in that space where the opposites meet that I usually find work to be the most interesting and where I feel the most alive and excited about making my own work. I have always been more interested in stories or characters where things are not fully one way or the other, that’s also not how things work in real life. I’m interested in ambiguity and complexity even if that means to feel the terror that comes with it.

Overall, I’m really fascinated by the power of our subconscious minds. Or to say it with Freud: “The mind is like an iceberg, it floats with one-seventh of its bulk above water.” I’m interested in what’s going on under water and finding a way to express whatever I discover there. And when you find a voice for it or give it a stage, you’re going to experience the uncanny. To me, the uncanny is the line where the familiar and the foreign meet and I’m trying to walk on that line in my work.

Lying Still at Gallery 295

RS: What artists have you been looking at lately?

BP: I’m not spending too much time looking at photography these days. I’m currently a bit more inspired and excited when looking at sculpture and installation-based work, like Louise Bourgeois (my all time favorite). Eva Hesse and Alina Szapocznikow are both so wonderful and then there is the Canadian artist Shary Boyle whose work I really admire and have followed for a long time. Other Canadian artist I’m deeply moved by are Janet Cardiff and George Bures Miller. Their multidisciplinary play with topics like the power of our subconscious minds and memory is so powerful and stuck with me since the first time I came across their work.

RS: I know you love gelato. What's your favorite flavor?

BP: I like all the milky creamy flavors and not so much the fruity ones. You don’t find Malaga (vanilla cream with raisins and a splash of rum) very often, so every time I come across it, it’s a must have.

RS: What's next for Birthe Piontek?

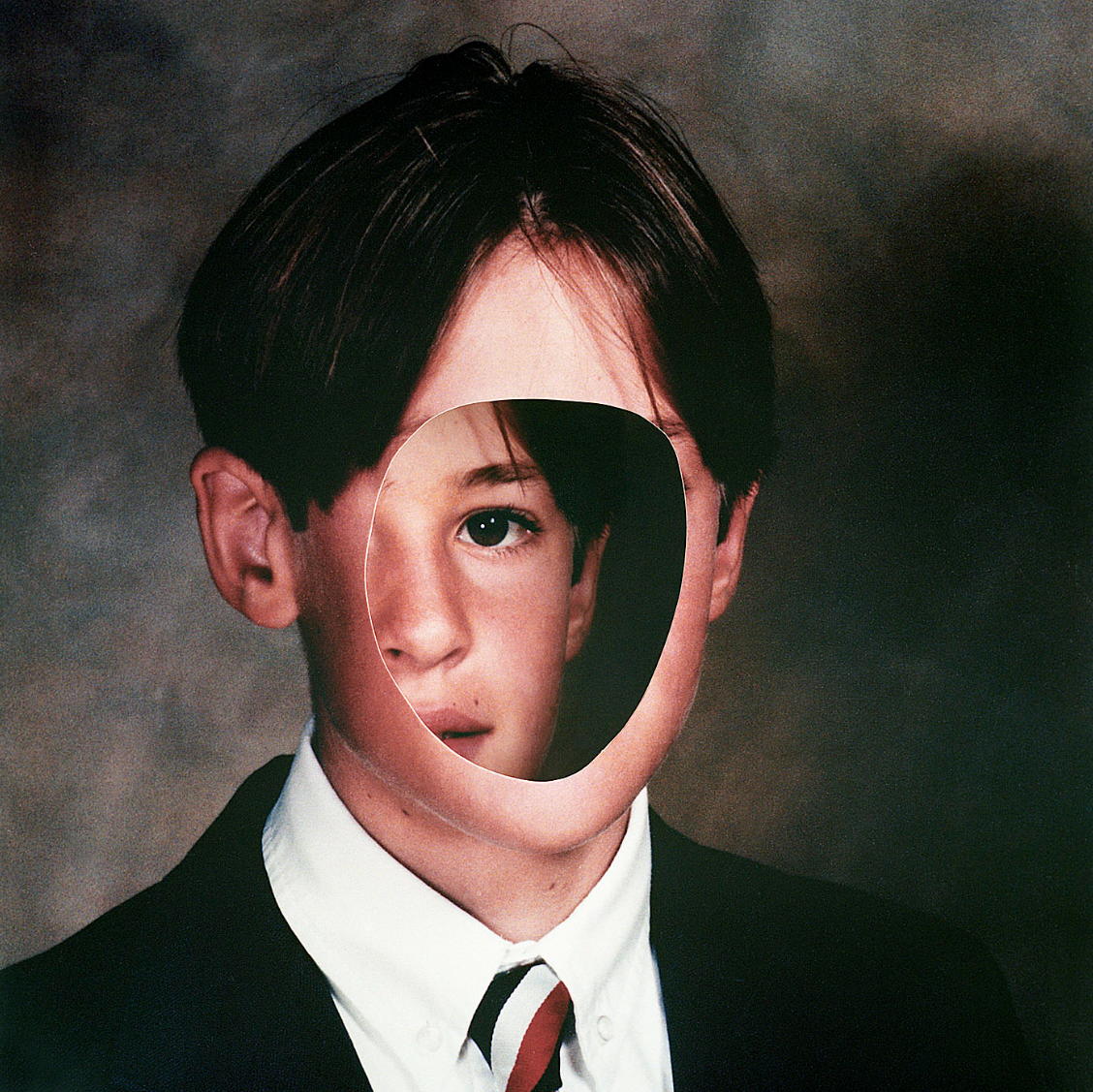

BP: Over the last 5-6 years I’ve been working on and off on another project, called Abendlied (in English: Evening Song) It’s a project I work on every time I’m visiting my family in my native country Germany.

The project deals with the universal themes of growing up and letting go. It focuses on memories and relationships that have shaped me and make up the core of my identity. What the work does for me is essentially distilling down that feeling of coming home and the tension between the feeling (or illusion) of everything still being the same while at the same time knowing everything is changing and coming to an end. It focuses mostly on my mother and her slow vanishing due to dementia as a metaphor for the slow dissolving of a place that was once so familiar and has become somewhat strange and distant.

In the project, I’m working a lot with everyday, household objects and clothing again in the form of still lifes and am returning to my first love and interest in portraiture. This project will mostly be “straight” photography and I’m in the process of editing and turning it into a book.

All images © Birthe Piontek