Q&A: brandon anschultz

By Jessica Baran | June 3, 2021

Brandon Anschultz’s (b. 1972, Newport, AR) practice is centered around painting and all of its constituent parts — from the viscous, gestural media itself to the wood, MDF, canvas, foam, plastic and beyond that compose its myriad substrates and internal architectures. These raw elements are often recomposed or deconstructed altogether, resulting in endless formalist interrogations that move fluidly between two-dimensionality and sculpture. While Anschultz's visual language appears abstract, the stories and histories encoded within his work are not. Rather, they speak to larger, queerer narratives about self-control vs. self-liberation, and the very nature of storytelling as a spectrum of careful disclosures.

Anschultz has exhibited extensively, including solo presentations at the Contemporary Art Museum St. Louis (where he was a Great Rivers Biennial winner); Regards (Chicago, IL); Philip Slein Gallery (St. Louis, MO); Flood Plain (St. Louis, MO); Laumeier Sculpture Park (St. Louis, MO); Longue Vue House and Garden (New Orleans, LA); as well as group exhibitions at venues such as projects+gallery (St. Louis, MO); the Chicago Arts Coalition (Chicago, IL); the Elmhurst Art Museum (Elmhurst, IL); White Flag Projects (St. Louis, MO); La Esquina Gallery (Kansas City, MO); Tiger Strikes Asteroid (Philadelphia, PA); Front Desk Apparatus (New York, NY); and Monte Vista Project (Los Angeles, CA): among many others. He has been awarded residencies at ACRE (WI/IL) as well as the Cite des Arts International (Paris, France). He is the Director of Washington University in St. Louis’s Des Lee Gallery, where he has facilitated and curated numerous exhibitions for the past 12 years.

Jessica Baran: Hi Brandon, thanks so much for having me over to your studio — our first meeting like this since the pandemic! What a joy it is to finally reconnect, let alone in person. When we first attempted this interview — which was dramatically cut short by the COVID outbreak and subsequent shut-down last year — we talked about the work you made for your 2017 solo show at Flood Plain, "Time Won't Give Me Time." That exhibit was more narratively explicit than anything you'd done over the past two decades, which has predominantly hewed to more abstract modes. But we also talked about how you've always encoded queer imagery in your work, and how encoded language itself is so much a part of queer culture — like your use of handkerchiefs as substrates for your paintings, in reference to the Hanky Code, or the fact that your wood substrates have a triangle embedded in them.

Brandon Anschultz: Yes, that’s basically a French cleat, but I expose it so the triangle is visible. A nod to the queer triangle, but also to elevate the panel as an object. Something purposefully and strategically made.

JB: Or, how many of your paintings happen to be in the shape of Arkansas, your home state. Autobiographical elements have consistently appeared in your work. It's just the degree to which you want to make those elements explicit to a broad audience.

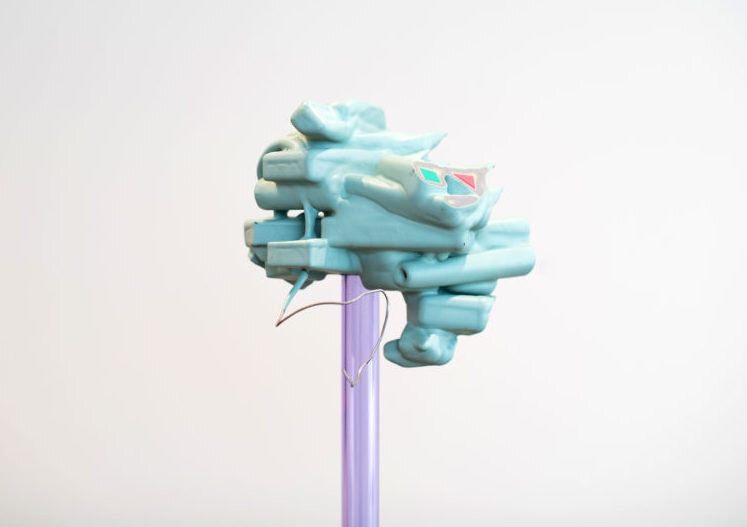

Blue and Purple Pocket

Acrylic and alcohol based ink on canvas, mounted on wood panel

8.5 x 11 inches

2021

BA: Totally. What's interesting to me is, say, when you're within a certain group, and you can have a conversation that has a lot of personal or collective history built into it that would make no sense to anyone outside of that group. I think some of it goes back to what made me not want to listen to Top 40 music when I was a kid, and want be part of a punky/post-punky alternative scene.

JB: So this a Gen X thing?

BA: Ha — maybe. I'm quintessentially Gen X, I know that about myself. But I think there's also more to it.

JB: A kind of suspicion of, or apprehensiveness about, broad accessibility? I get that.

BA: The work in that show from 2017 — which was titled after a Culture Club song, speaking of formative childhood music culture — was all about coming of age as a young gay kid in the late '80s during the AIDS crisis and growing up petrified and how that fear affected every part of my life — from the relationships I got into to the places I chose to live. It was a terrifying time, and I'd never been able or willing to make work about it before because it felt too close. Losing people, losing lovers, thinking I was going to die — that whole body of work was my attempt to grapple with and look more closely at that moment and all that came out of it. It manifested in pieces that were far less coded and more image-based than what I usually make.

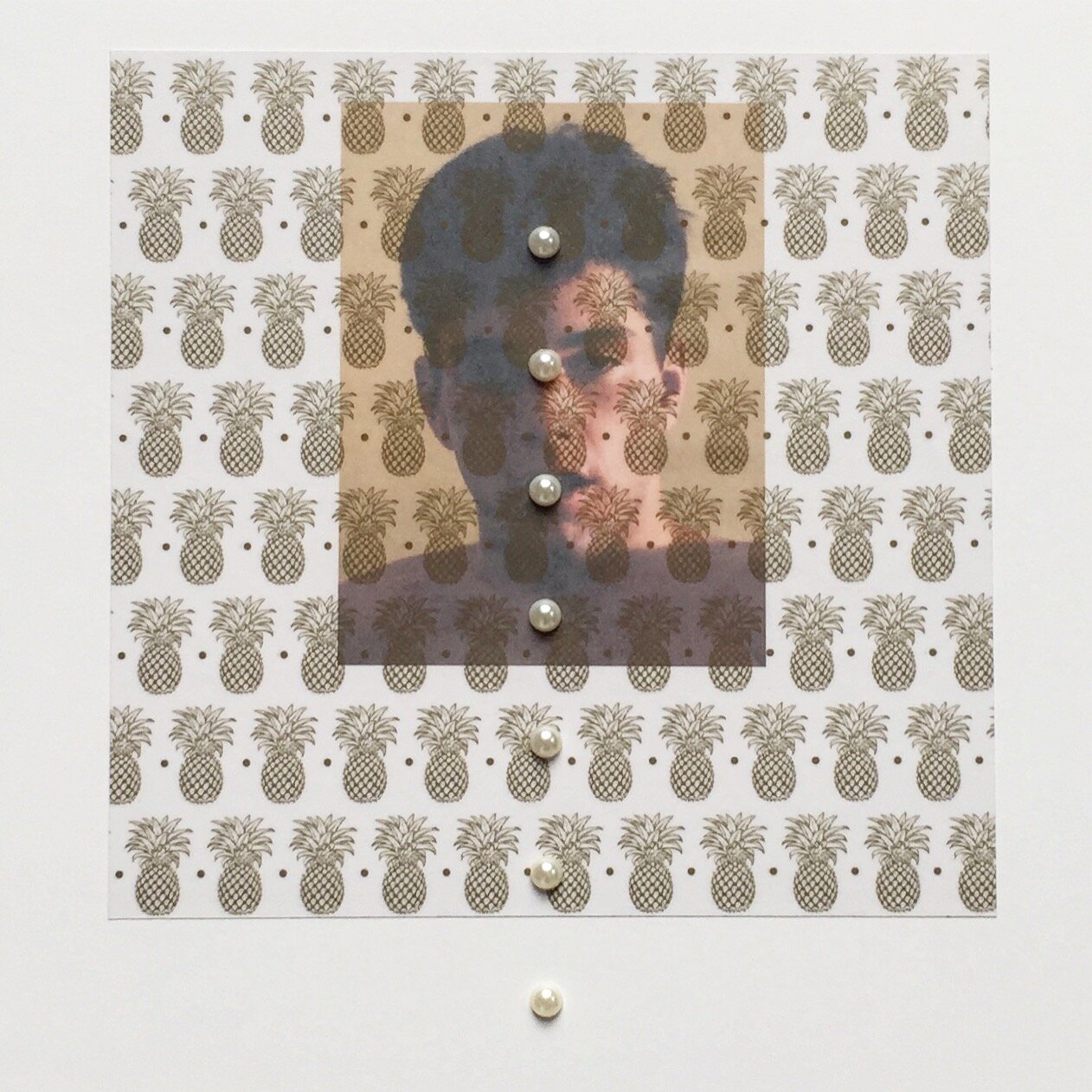

David (Flowers)

Appropriated image, printed Mylar & pencil on Bristol

2017

After the show closed, I tried to keep on that path and dig deeper, but it just wasn't satisfying. Now, I'm trying to get back to the things that made me originally turn to art, one of which is process. My favorite part of being an artist is that slippage that happens when you're able to spend time in the studio every day for a couple of weeks and lose time in the process of making — just feel immersed in the moment-to-moment satisfaction of mixing color and thinking about everything and nothing at once. It's hard to put into words. But I've gone back to my default setting of making these little 8.5 x 11 paintings that I've been producing for as long as I can remember. They're modular and call to mind drawings on typing paper, which is the first kind of art I made.

JB: I love the idea of literally going back to the drawing board, back to basics, after a creative reckoning of some kind. What you're describing makes me think of the difference between writing first-person narrative prose and writing poetry. They're both capable of discussing subject matter, but one form is a little more removed, or opaque, than the other. In many ways, it's all about how you prefer your story to be heard, and by whom.

BA: Yeah, that makes sense to me. Coming out of that more narrative body of work made me realize that I wanted to return to some of my more fundamental inclinations toward art, which are more abstract and removed from obvious legibility.

Think about it: in the late '80s, when you were watching television or movies, who were the cool weirdos? They were artists. Anything that wasn't rural Arkansas was what I was interested in, which came in the form of music, music videos and old movies. Like Ann Magnuson. I was a huge fan of Ann Magnuson (a friend had given me bootleg VHS tapes of stage performances in New York). That's pretty fucking obscure for a kid in Nowhere, Arkansas. Or the queer sensibility that was nurtured by my friends Joe and Jim, who were my queer parents, basically. I met them when I was 16 at the video store I was working at in Searcy, the biggest town closest to my hometown of Judsonia. They were maybe 20 years older than me and had been together for 15 years, and are both dead now. They introduced me to Bette Davis and Bette Midler and John Waters; they introduced me to drag via Charles Pierce, Lypsinka, Divine — basically everything fantastic and awesome.

Pink Arkansas

Acrylic on wood panel

8.5 x 11 inches

2020

JB: So art was about developing a private aesthetic, or language.

BA: Definitely. Art has always had an aspect of that in tandem with, like I mentioned before, a kind of escape into process. The very making of these little paintings I've been producing is predominantly what they're about. Over the course of a month, I can prepare about thirty of them in the wood shop behind my studio. Before any painting happens, it's literally two weeks of substrate preparation — cutting, assembling, sanding and finishing. I have my own recipe for gesso, which involves mixing together a couple commercial brands and adding plaster and marble dust. I put the first layers of gesso down thinly and haphazardly. Everything at that point is chaotic and dusty and crappy — and then becomes progressively neater, progressively smoother. By the time I get the last layer on, I'm hand-sanding with 500 grit paper to get these really soft, supple, baby-butt smooth surfaces with finished sides. After that, I just let them sit for a month. I think of it as like baking, in a way. They're getting ready. Then, for two or three weeks thereafter, I'll work on painting seven or eight of these little panels at the same time.

JB: How do you then determine the imagery?

BA: Right now I'm re-reading Josef Albers' "Investigation of Color," which is gospel. I mark pages that describe color strategies, such as simultaneous contrast or local color, that I then use as jumping-off points. I try to closely replicate those strategies until I feel like I can I stop referencing the book and focus only on the color relationships in my painting. I then try to figure out how to fuck up these naturally harmonious relationships with added colors that aren't supposed to work.

At some point I shift to textures — allowing some brushstrokes to be visible while making other passages really flat and machine-perfect. I'll get the piece to a point where it's pristine and beautiful and then I'll, say, spray water on it so it starts to melt and move around in a way that I can't control. I'll then come back to it the next day and either try to fix it or fuck it up further. Each of them usually involves five to eight days of work. And then at some point, they're just done.

Pink / Green (after Albers' "vibrating boundaries" chapter)

Gesso, acrylic and gouache on wood panel

8.5 x 11 inches

2021

JB: This feels like an extension of what your practice has always been engaged in, in terms of breaking down the constituent elements of painting — whether it's literally grinding up canvases whole-cloth and reconstituting them as sculptures or, in this case, doing a very close interrogation of color, which couldn't be more elemental to painting. Paint itself has even taken on forms in other projects you've done. All of these processes and ways in which you describe them sound so emotive, too, and full of content on their own.

BA: I really like getting to a point where I don't have any control anymore, because so much of my work is about control — about making really specific decisions and shapes and marks. I like when I can get to a place where the material does the work.

JB: I think that's what's especially magical about these new little paintings. They enact a kind of sleight of hand in which they seem easy and fluid and spontaneous — almost sketch-like — when in fact they're the product of an enormous amount of labor and expertise.

BA: I agree with that 100%. It's a lot of preparation and then one or two confident moves, marks or mistakes. Letting it be, but also really planning for it to be that. If that makes sense.

I realize that so much of what I'm doing now can be traced back to how I was trained as an artist in undergrad. I originally went to Louisiana Tech — which is in Ruston, Louisiana — in order to study architecture. And I ended up in Louisiana by way of Monroe, because I'd dropped out of school in Arkansas to chase a boy who lived there.

JB: What was Louisiana like?

BA: Monroe had a really good drag scene, actually, because it's on I-10, which travels between Dallas and Atlanta. Queens from those cities would do shows in Monroe. The first live drag performance I ever saw was at Corky's River Park Saloon in Monroe. Ms. Jane Deaux — D-E-A-U-X, thank you — performed and she was fantastic. There was another gay bar in Monroe called Hot Shots, which is where my boyfriend Christopher and I met.

I ended up working for Corky as a "hateress" for a couple of years, including while I was at school. Corky, the owner, was this old queen who was in a relationship with a woman in her late '70s named Ms. Ruby, who floated his entire enterprise. He also had McElroy's Piano Bar, which, during the day, was the lunch spot for rich ladies from Bayou Desiard. At McElroy's, I would serve three martini lunches to businessmen and old ladies who called me Gatsby because I had slicked-back hair and blue eyes. At night the place basically became a gay bar, with a live piano player. Then, I would mix martinis and flirt with the married queens, who would come in with their wives. It was definitely a scene. I met some amazing people during that time. It was pretty great.

I stayed in Monroe for about two years before moving to Ruston to go to Louisiana Tech. Ruston is about 30 miles away from Monroe on the freeway. I would drive back and forth between the cities to work three shifts on the weekends at the restaurant to pay for school, which is something you could actually still do in the early '90s.

I was in the architecture program for my first three years (it was a five-year program). At the beginning of my third year, I did an internship at a little architecture firm; by the end of that quarter, I dropped out, because I realized I couldn't be around those people for the rest of my life.

So I switched to their art program, which was run by four teachers who were traditionally trained. One of them, Peter Jones, taught most of the intro classes — including color theory, and Albers' book, and how to make almost anything, from frescos, encaustic and hand-made oil paint. It was very drawing-focused, so we had three drawing courses per quarter. It was super traditional. Contemporary art at that school literally stopped at 1980. But it was really great, in retrospect. That little state school program actually informs all that I still do now.

Switching to art at that time was about quality of life more than anything else. I could not imagine working in an architecture firm, mainly because of where I was and the kind of people I was around. Of the fifty-whatever people in my architecture class, only seven were women, and I was the only openly gay person. It was stifling. I loved the math, engineering and designing aspects of it. But I despised most of those people.

JB: I think I remember you saying that you made landscapes at that time.

BA: Yes. I was doing a lot of collage with acetone transfers, and some little tiny engravings that were three inch by one inch. They were all little Arkansas landscapes — rice fields and telephone poles — and abstracted from either photographs I was taking with my little [110] camera, or sketches that I was doing on my driving commute between Ruston and Monroe. My color palette hasn't even changed that much. That one color theory course really changed my eye.

JB: When did you apprentice with a master carpenter?

BA: I started working at The Woodchuck while I was still in school and then stayed a year after. The main thing the shop produced were replicas of architectural elements — wooden finials and copies of classical architectural details and moldings. But we did some decorative stuff, too, like window treatments and cabinetry. I was initially hired to work in wood finishing — I basically sprayed lacquer for a year — but then I did a rotation through the entire shop.

It was great. There would be times when I would spend six weeks doing nothing but cutting out the same shape on a bandsaw. Or gluing up stacks of wood. I was trained to sand things for months on end, and now I enjoy it. I definitely clocked in 10,000 hours. But I really think those things informed my making practice more than anything else — that school, that apprenticeship and the experiences I was having while in Monroe and Ruston at that time. You can see all of it, in a way, in these little paintings. This one's good [picking up Op Pocket in Blues and Green] — I worked on it for quite a while.

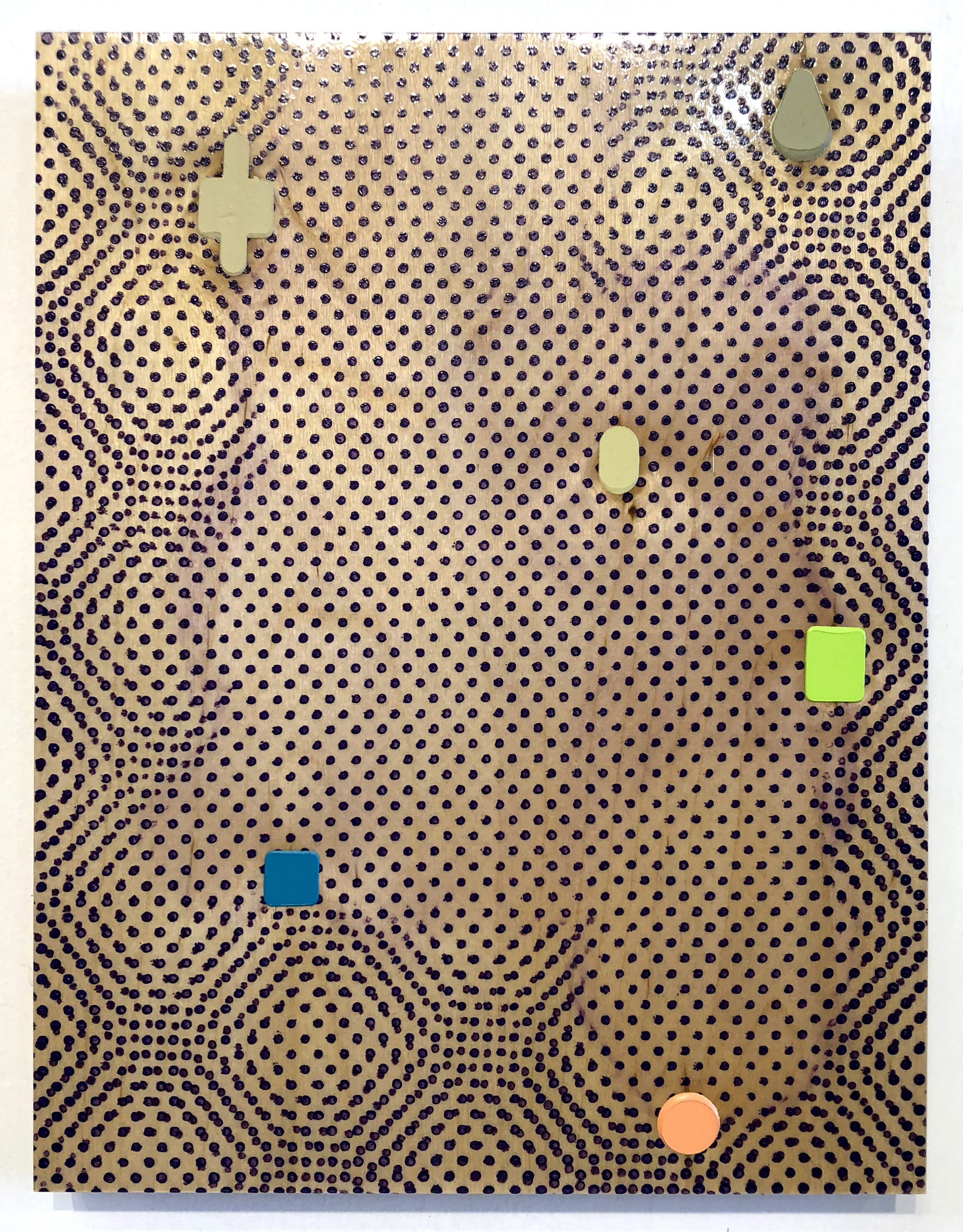

Op Pocket in Blues and Green

Acrylic, gouache, block printing ink and lacquer on wood panel

8.5 x 11 inches

2021

JB: It's beautiful. It has some Op Art qualities. And resembles a very reduced Arkansas.

BA: Well at some point, they're no longer Arkansas. They become back pockets.

JB: Oh — bringing back the Hanky Code! I love that.

BA: So, they're either pockets or Arkansas.

JB: Always encoded. Amazing. Thank you so much again, Brandon, for having me over and talking with me. I love hearing your stories and looking at your work.

BA: Thanks so much for coming by! It's always good seeing you and being able to share new work with you. So glad we could finally continue our conversation.

All images © Brandon Anshultz