Q&A: Danny Giles

By Rafael Soldi | September 10, 2020

Danny Giles is an artist and educator based in Rotterdam. He serves as Course Director of the Master of Fine Arts at the Piet Zwart Institute for Postgraduate Studies. His work uses varied material and performative approaches to address the possibilities and dilemmas of representing and performing identity and to reveal hidden languages of power within mundane objects and spaces. Giles received his MFA from Northwestern in 2013 and BFA from The School of the Art Institute of Chicago in 2011. He attended the Skowhegan School of Painting and Sculpture in 2013. Giles’ work has been exhibited, performed and screened at venues including The Jacob Lawrence Gallery, Seattle WA, Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago, the Mary and Leigh Block Museum, Evanston, IL, El Museo Tamayo, Mexico City, and the Contemporary Arts Museum Houston.

Rafael Sold (RS): Hi Danny, thanks for chatting with us!

Danny Giles (DG): Thanks for reaching out, Rafael.

RS: You work primarily around themes of representation, which is a broad and ambitious topic to take on. Is this why you work across many different mediums? How does each material and process provide a language for addressing the many dimensions of identity?

DG: I’ve always been drawn to different ways of making things and I think the range of approaches in my work is a way of thinking and feeling through different materials and finding different modes of embodiment through images, objects and spaces. I’ve also always tended to seek out knowledge about a lot of different subjects, so maybe I’m just a kind of generalist thinker and maker. There is a connection to my interest in representation and identification. Representation is all about appearing and being legible for the other and there are really endless ways to identify or comprehend a person, object, or image. How we appear for each other is informed by so many different influences (culture, education, language, geography), the complexity of what it means to look at and understand the world is really exciting to me and offers so many different entry points for my work. We experience the world through so many various materials, signs and directives for how to experience our bodies, so its important for me to process and re-present the world through my work through lots of different materials, forms and techniques.

RS: I’m particularly interested in your use of performance, because the moment the body becomes the material and the language, you’re introducing a different type of power—a “material” that carries memory and trauma in ways other mediums don’t.

DG: Performance can be a really powerful tool to find connection with the content of the work and with an audience. We respond to bodies around us in so many micro and automatic ways on a daily basis, to make bodily dynamics present in an aesthetic context can bring up strong emotional responses in the viewer and in the performer. I started making performance actions as a way of connecting with my work in a new way with movement and presenting the objects I was making in public spaces. I was interested in provoking a more visceral response in the people who saw me and my work and in questioning how my body signified in relation to physical space and material objects. I’m often looking for a way to reactivate things that are already a part of our daily lives and visual culture and give them new embodiments. I came to performance actions through a turn to object-making and still its usually the case that thinking about a new performance for me is also thinking about a new sculpture. From the earliest performative works, they were always anchored by an object that facilitated or directed bodily movements. Somewhere in performing with or around the object that is familiar to our reality (a protest sign, security camera, a museum artifact) Performing with these things allowed a created a moment of recontextualization or transformation. There is the possibility for a shift in the significance we assign both the object and the body.

RS: A recurring strategy in your work has been to ask what can be abstracted within representation. Can you talk a little more about that?

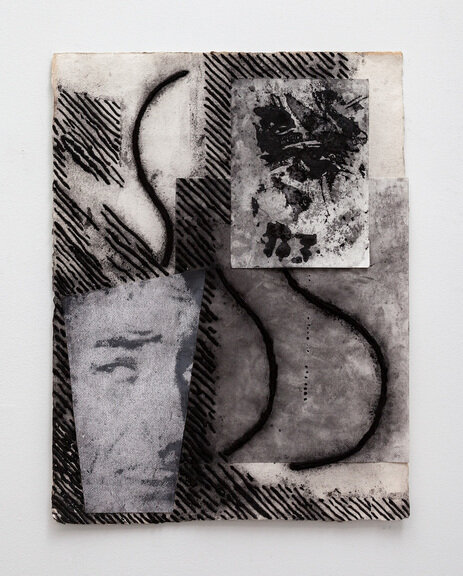

DG: W.J.T. Mitchell has written about how images and words have more in common than we tend to think. We think that we just “read” words, but we also perceive them as kinds of images with familiar shapes that evoke meanings in our minds as immediately as pictures can. Similarly, pictures can function very much like language in signifying meanings through line, shape, color, form, and context. Understanding this helps in not taking representations for granted. It’s common to take representations at face-value. We tend to think that what we see is what is there, but when we realize that what we see we are also reading and interpreting as culturally conditioned and based in language, then we can begin to deconstruct representations and better understand how power conditions what we see. Hardly any meaning is completely self-evident and I use my practice to play with this idea. With abstraction, we are also dealing with visual codes that represent certain historically and culturally specific meanings. As signifiers of style or historical movements, many abstract motifs have representational force as much as any other language so they have cultural signifying power that challenges the idea of the “pure form” that some of us may idealize in the appreciation of abstract art.

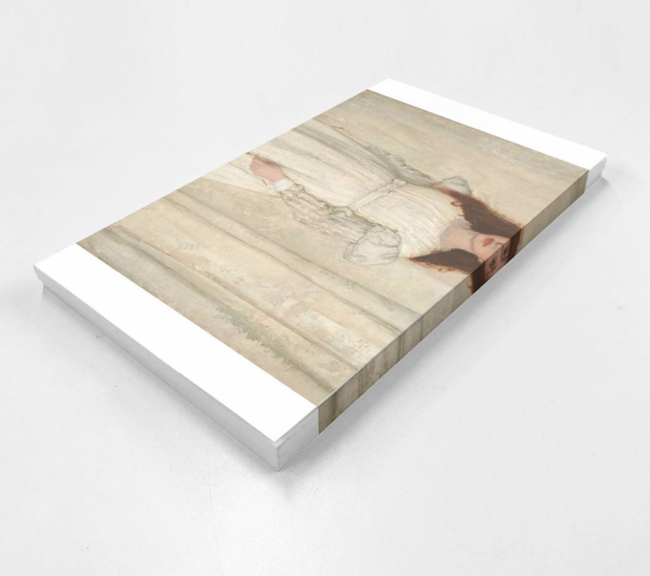

RS: In your recent exhibition, The Practice and Science of Drawing a Sharp White Background at the Jacob Lawrence Gallery (“the Jake”), you address how Western aesthetics have structured whiteness. Why did taking on Whiteness, specifically, feel important to you at this stage in your practice?

DG: I’ve also had this question of Whiteness in my mind for quite a while as a logical next phase of identity politics work. I wanted to do with Whiteness what Black artists had done and been expected to do with Blackness for so long and excavate its imbrications with visual form and make it critically visible to itself. With the show at the Jake, I wanted to think through the relationship between visual technologies of representation and the formalization of race, how traditional materials and techniques of image-making in the West and artistic practice were foundational tools used to define the aesthetics of White supremacy. I was particularly interested in drawing as the central building block of visualizing and quantifying the world. Linear perspective, light and dark are all technologies used to define a Western visual and scientific point of view through supposedly rational and objective study but ultimately founded on the centrality of patriarcal White supremacy. We see this manifest in the founding figure of Western art history, Johann Joachim Winckelmann, who wrote art history’s founding text which places white statues of naked Greek men at the center of the Western beauty ideal, literalizing the fetishisation of pure whiteness in Western culture. Another figure that I was mining for imagery was William Hogarth, who famously depicted scenes of class and politics in his cartoons and paintings in 16th century Britain. He would have been aware of Hogarths research which influenced his own aesthetic principles. Hogarth’s focus on depicting class within British society provides a look into the early formations of Whiteness as it was taking shape as a social, economic, and political institution in the West.

I was also thinking of the Whiteness of the University of Washington and the town of Seattle where the Jake is located. The set of drawings and the installation I presented there were self-reflexive works about image-making and self-conscious of their setting within the bastion of Whiteness. Something I discussed in the lecture I delivered there through The Black Embodiments Studio, was the relationship between contemporary White suprematist movements and the Greco-Roman aesthetic of Classical Europe. When the White suprematist group Identity Evropa marched through Seattle a few years ago, they left behind propaganda materials featuring imagery of the same pure white Greek statues that Winkelmann also fetishised.

RS: Earlier this year you collaborated with the Jacob Lawrence Gallery to guest-edit the 4th issue of the MONDAY journal. How was that experience? How did you approach this project?

DG: Working on MONDAY was a great experience and helped me to keep unfolding some of the ideas of the exhibition at the Jake with some writers whom I admire. I used my show at the Jake as a starting point to move deeper into exploring Whiteness as an identity that leverages its power through invisibility. The other side of the coin was to give some attention to artists of color who in some way refuse visibility or representation to reclaim autonomy, or to flip expectations of the visual to deliver a critique of the conditions imposed by Whiteness. The edition of MONDAY is called “White Pictures” to invoke this dual address of Whiteness as an unmarked category of being and to think through disappearance, abstraction, and opacity as tactics to evade the violence of representational traps. For this publication, I wanted to work with artists, writers, and scholars who could come at these questions from really different and complementary angles so you’ll find contributions from diverse perspectives in the book. There are also really different forms of writing and research involved—from art historical analysis (Angeline Morrison), to social critique (Sharmyn Cruz Rivera, Ruby T and Latham Zearfoss) and close readings of the work of contemporary artists and language (Tomashi Jackson, Risa Puelo and Gordon Hall).

RS: I’m really curious about your recent exhibition The Thing and its Double. I’d love to hear more about the title, and more specifically about the piece Dancers.

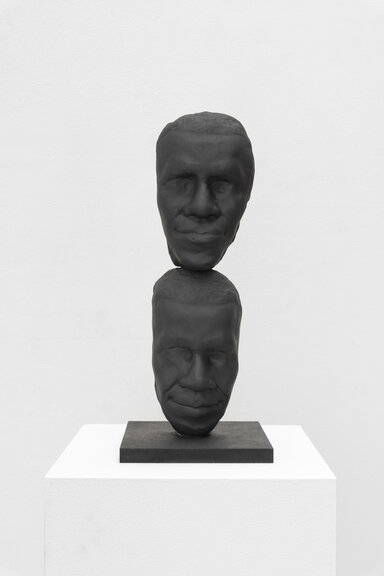

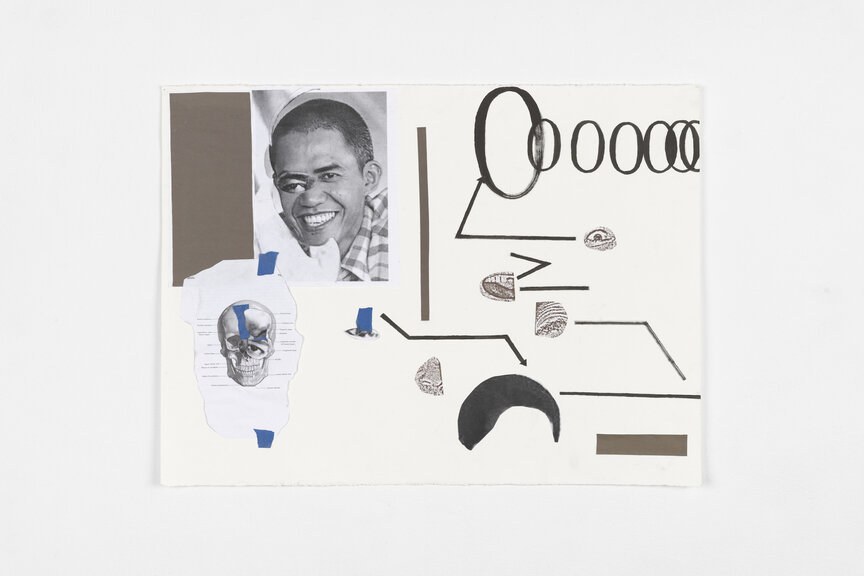

DG: The title of that show directly references an essay by Achille Mbembe in which he writes on the role of visual representations in autocratic regimes. This text was brought to my attention by Christine Goding who worked with me on the text for the show at the Chicago Artists’ Coalition. She brings in Mbembe’s text to think through the multiple doublings of the figure in my work that is really what the show is centered around. In Mbembe’s reading of the autocrat, he disseminates his power throughout the country through the ubiquity of his image which pervades the consciousness of the people. This show had a lot of work that enacts a kind of doubling of bodies, and various likenesses. The show brings together different bodies of work from the past several years where I have experimented with the abstraction and appropriation of different likenesses. I think of this show as collecting all of these different proxies for my body and the bodies of others. Each work hinges on the dialectic of presence and absence. “Dancers” was one of the more open-ended and poetic works in the show. It’s made up of 13 men’s cotton t-shirts that I bought from second-hand shops in Chicago and dyed indigo-blue. The cotton tees and the indigo dye both have historical relationships to labor and Blackness. They are also these figments of a collective body that are somehow moving in unison to defy gravity. The blue connects the sky with the ocean in my mind, both sites of historical and spiritual resonance. In the show, I was thinking of “Dancers” as a crew of backup dancers who were there to reinforce the themes that were made more explicit in the other works and leave space for the viewer to project themselves into the space of suspended movement—flying, falling, floating, or dancing.

RS: You’re now living and working in Rotterdam, Netherlands, a country that has a relationship of its own with issues of race and representation. Your work has been largely informed by the midwestern American experience, and concerns primarily American identities. What does this change of landscape mean for your work moving forward?

DG: I’d say that my practice has been shifted as much by changes in my living and working space as it has by leaving the US. I’m living in and working in the same small apartment space and I've slowed way down in terms of production, making pretty quiet observational drawings that are little meditations on visual influences, some of them drawn from my surroundings here, others from personal and cultural archives. I started using Google Translate in order to shop at the grocery store and that led to some drawings based on bad or incomplete translations. I’m thinking of the drawings I’ve been making as little foot notes that I’m collecting, maybe on the way to other things.

On the level of content and thinking about issues of representation and identity here, I’m still learning and observing. I’m interpellated differently here and I want to spend more time getting a feel for that. In a way, it’s like stepping into a different body where the possibilities of how someone may be reading me visually here seem more open than in Chicago. I don’t feel that I necessarily need to bring the same conversations I was having in the US context here and I’ve been spending more time reevaluating how I make and what is possible in this present moment. I’m always interested in issues of legibility and being here has me thinking in new ways about the process of identification and interpretation. I will be following that and thinking about how those dynamics are both familiar and different for me here.

RS: As a teacher, you work within an institutional system that plays a big role in the struggles that your work seeks to highlight. How do you use—or not use—your role as a teacher in the university system to impart new ways of thinking on young minds?

DG: Education is a practice of claiming and addressing power so I try to lead by example and center practices that critique and expand canons of knowledge. It’s useful to examine art practices in the context of the social and political moment in which they were developed. What you learn gains relevance through an understanding of the context you’re working in. In teaching art practice and theory, there are many ways to examine context—historical, cultural, social, bodily, relational—these are entry points for students to test the relevance of their work to the world. Critique is a way of questioning the stakes of the work and testing how well the things we make hold up to their ambition. It takes nerve but it also takes honesty, which can’t be taught but can be challenged through the rituals and relations of teaching and learning.

RS: What are you reading, watching, or listening to right now that has got you thinking and inspired?

DG: Reading: “White Innocence” by Afro-Surinamese Dutch writer, Gloria Wekker, is a great introduction to and vivid dissection of the Dutch racial imaginary. It has been an important orientation in understanding how race, gender, and class operate on a social and psychological level in the Netherlands. This summer I also read “Parable of the Sower” by the great science-fiction visionary, Octavia Butler. Butler describes an apocalyptic United States through scenes of constanƒt wildfires, the collapse of the social fabric and talk of a return to slavery by way of the privatization of public services—so to say the least, the book is painfully prescient, as many others have pointed out before. Watching: I recently finished the one and only season of “Watchmen” and was blown away by it. There are also a lot of themes in it that parallel our current science-fiction/racially contentious and violent present. I'm currently watching “Lovecraft Country” which also combines historical narratives of racial violence in America with science-fiction in really exciting ways. The director, Jordan Peele, doesn’t explicitly deal with H.P. Lovecraft but dips deep into the historical context and narrative tropes of Lovecraft’s racism and uses him to show talk about American white supremacy. Listening: Some favorites right now are Beverly Glenn-Copeland, Kaitlyn Aurelia Smith, and Laraaji.

All works © Danny Giles