Q&A: fatemeh biagmoradi

By Abbey Hepner | December 21st, 2017

Fatemeh Baigmoradi (born in 1984) is a visual artist born and raised in Iran. In 2012, Baigmoradi moved to the USA. She received her Master of Arts in photography at the University of New Mexico in 2017, and in 2008, she earned her Bachelor of Fine Arts in photography at the University of Tehran. The themes of loss and identity define much of her work, both directly and indirectly. Transitions in her life, both physical and emotional, have also been critically influential in her work. Biagmoradi has exhibited her work internationally, in over twenty exhibitions, within the United States, France, Iran, and China.

Abbey Hepner: Thank you for taking the time to share your work with me. What led you to pursue your path as an artist?

Fatemeh Biagmoradi: Thank you Abbey!

I was born and raised in an art-friendly family; I have always been interested in concentrating my studies on a discipline within the broader field of art. From a young age, I thought about what it might be like to be a singer, while at other times, I felt eager to be an actress or animator. I developed my first roll of film when I was just fourteen years old, using photographs that my sister had taken. This was my first step into the world of photography and I fell in love with that. Since then, I have been confident with my decision to work as a photographer and an artist.

My parents did not pay that much attention to photography, even to their own family photos. Their lack of interest in photography made it all the more mysterious and desirable to me.

AH: You are originally from Iran and even though you were born after the 1979 Islamic Revolution, the impact of it seem to have greatly influenced you and the questions you contemplate in your work. Can you talk a little bit about the history and how your family was affected?

FB: Iran's revolution began with a popular democratic movement and ended with the establishment of an Islamic state. Before the Iranian Revolution, opposition groups tended to fall into three major categories: constitutionalists, including National Front (Iran), Marxists, and Islamists. All three opposition parties participated in the 1979 Revolution, but the Islamist majority began to slander and condemn the other parties; eventually they began to arrest, exile, and execute members of the oppositional parties. My father was a member in the National Front party that disbanded several years after the revolution. As could be expected anywhere, the members of the party occasionally took photos of their meetings, as well as social gatherings. What were taken as photos to show their social status and rank became documents to be used against them, in the space of a few years. My father and many others destroyed these photos due to the risk of being arrested.

None of my immediate family members were ever arrested because my family was part of the commonalty who were not against the regime. As much as I know they avoided political actions and even conversations after the revolution. The society lived in fear and Strangulation beside more economic pressure and anxiety that happened because of Iran and Iraq war.

In my city there is a train bridge. When I was a teenager I heard from one of my sisters that a couple of years after the revolution, the government hung three young Marxists under this bridge. My parents and my sisters were passing the area and witnessed the scene. My sister told that one of them wore a pair of jeans. Even now, after the years, whenever I think about the train, my city, and the bridge, I see that three young Marxists.

I am so relieved to be talking and expressing the fear that I feel as a result of these experiences. It is a huge relief for me.

AH: In your series, It's Hard To Kill you are using other people's family photographs to talk about collective memory and your own loss. This isn't the first time you have utilized found photos and family archives to grapple with and communicate something about your personal and cultural history. Can you talk about your relationship with these images? How does using found photos and other people's family archives share something about the collective human experience?

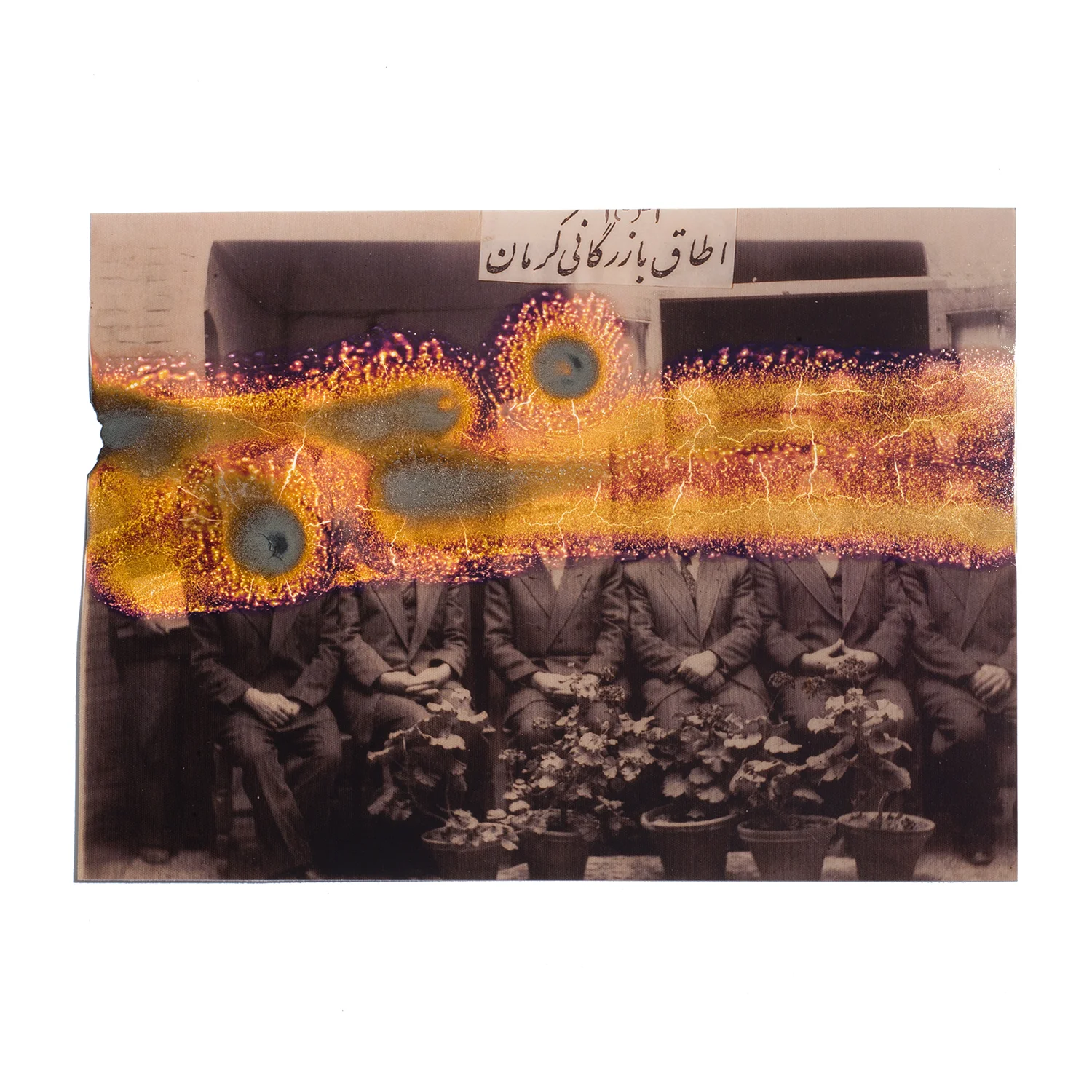

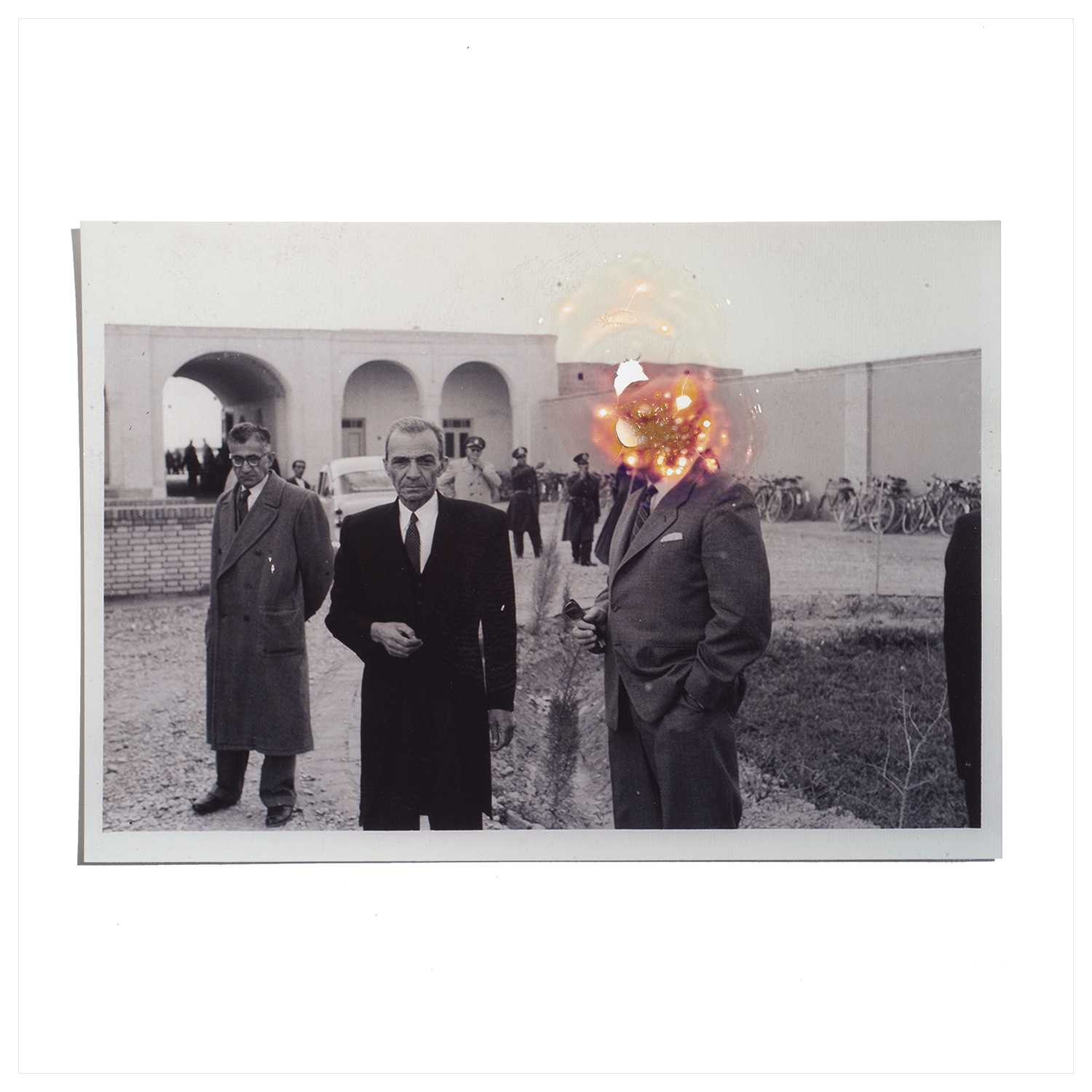

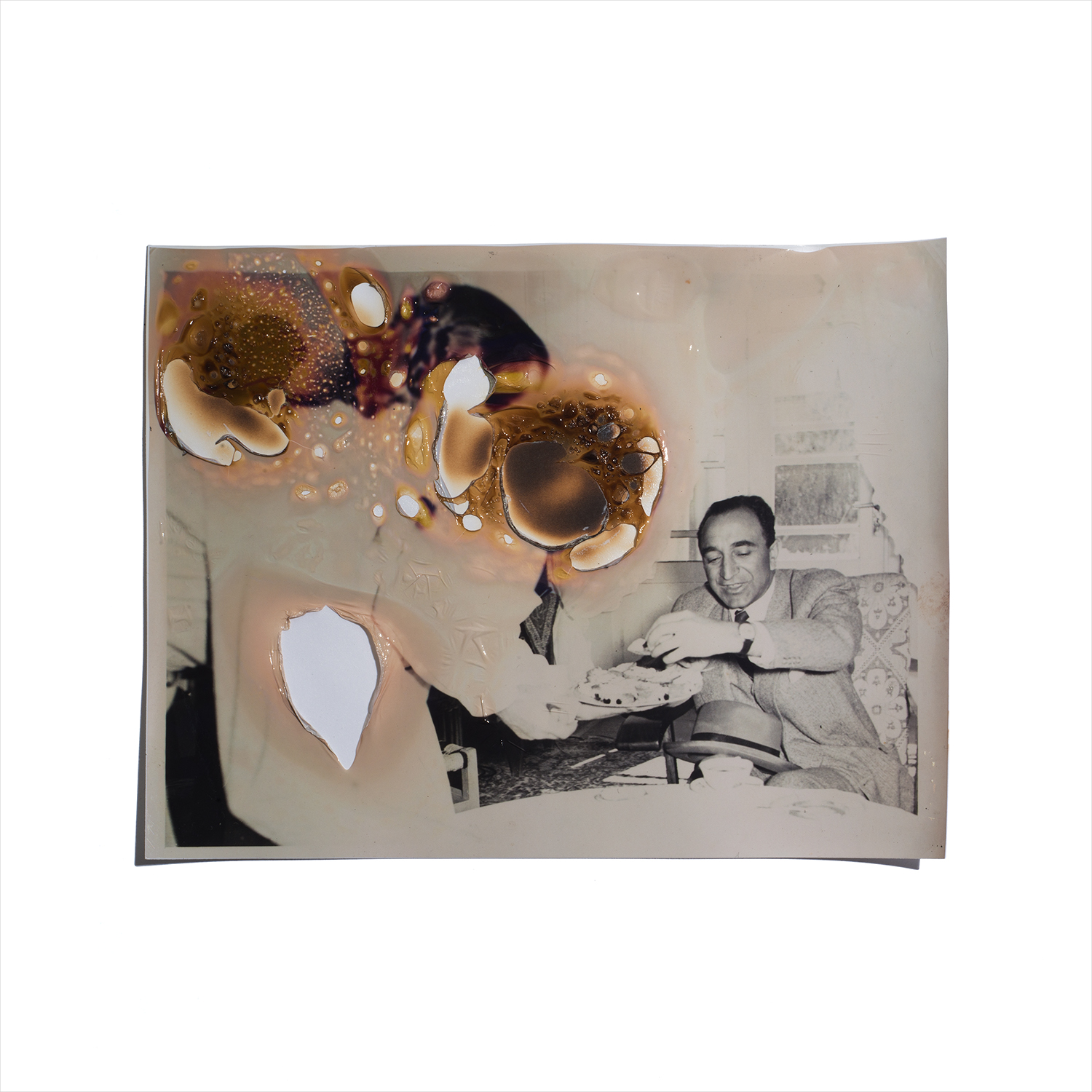

FB: I started to work with archival (family) photos from 2013. In May 2016, I went back to Iran to visit my family and collect more materials for my project. My short trip extended to 9 months, unexpectedly. I decided to take it as an opportunity to expand my archive. I met several families who destroyed parts of their photos after the revolution. I even received an album in which most of the photos were ripped to hide the face of the prime minister (who was executed after the revelation) I have explored other people’s family archives t in order to imagine the moments when my father burned the photos. It was a fearful ritual meant to protect my father, or at least not to harm him. I am making my work based on this true story that has happened over and over, for many different people from different nations, after social revolutions in the 20th century.

AH: Can you talk a little bit about what inspired you to make It's Hard To Kill?

FB: My parents did not have much desire to take photos. They have only a few photos of themselves from before the Islamic Revolution in Iran. My obsession with these photos, and with the photos we do not have, led to this project: It’s Hard to Kill. I was born after the Islamic revolution and during the Iran & Iraq war, so I grew up having lived through double sides lifestyle, along with many other kids. I had to be careful about what I said about my parents at school.

AH: The act of burning photographs seems to appropriately communicate something about fear and desperation. It's also a violent act. Why is this process important?

FB: It talks about self-censorship. My parents and many others desperately self-censored in order to feel safe.. The act of disappearing photos was highly emotional, even if not rational, in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction; the fear and anxiety that the society experienced at that time was acute. Any kind of censorship brings visible and invisible violence, especially when it affects collective beliefs and opinions. The act of burning mimics this violence and censorship.

AH: Are there challenges that you face as an Iranian in making the work that you want to make and communicating something about a history that was meant to stay buried?

FB: Yes, when I was collecting photos, it was a chance to find some of my father’s photos, by meeting his old friends, but my father did not like this idea. One of the families that gave me their photos did not want the photos to be seen in Iran if the faces were recognizable.

Last year, I tried to present my work in Iran, but I was told that I would have to rewrite my statement and censor it to be more cautious.

AH: How do manipulation and deception play a role in your work both conceptually and technically?

FB: Well, I am working with found photos now and I make my artwork by physically manipulating them. So that’s a fundamental part of my process. I exercise my voice through the manipulation of objects that already exist.

AH: What's next for you?

FB: I am not done with archival photos yet. I will continue working on unfinished projects that I have started simultaneously during last couple years.

AH: Thank you for sharing your story Fatemeh!

FB: Thank you so much Abbey! What a pleasure!