Q&A: Jessica Hines

By Hamidah Glasgow | May 25, 2017

Artist and storyteller Jessica Hines, uses the camera’s inherent quality as a recording device to explore illusion and to suggest truths that underlie the visible world. At the core of Hines’ work lies an inquisitive nature inspired by personal memory, experience and the unconscious mind. Hines began to cultivate her creative disposition early in life and her love of the arts led her to attend Washington University in St. Louis, where she earned a Bachelor of Fine Arts degree. Continuing to pursue her interests, she studied photography at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign where she received a Master of Fine Arts degree.

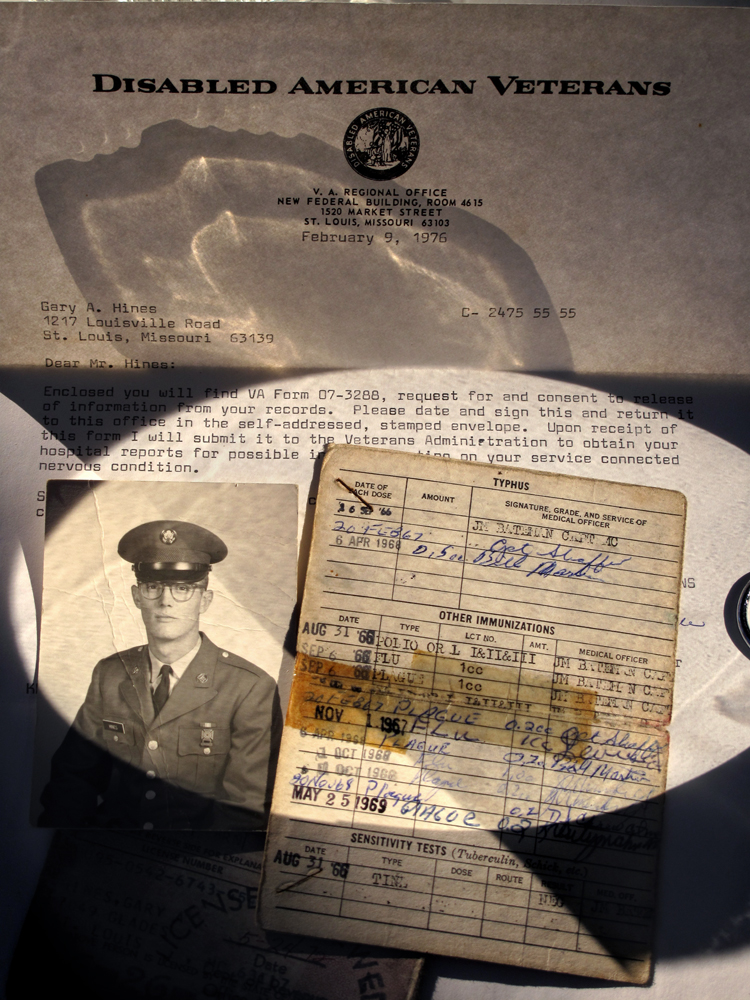

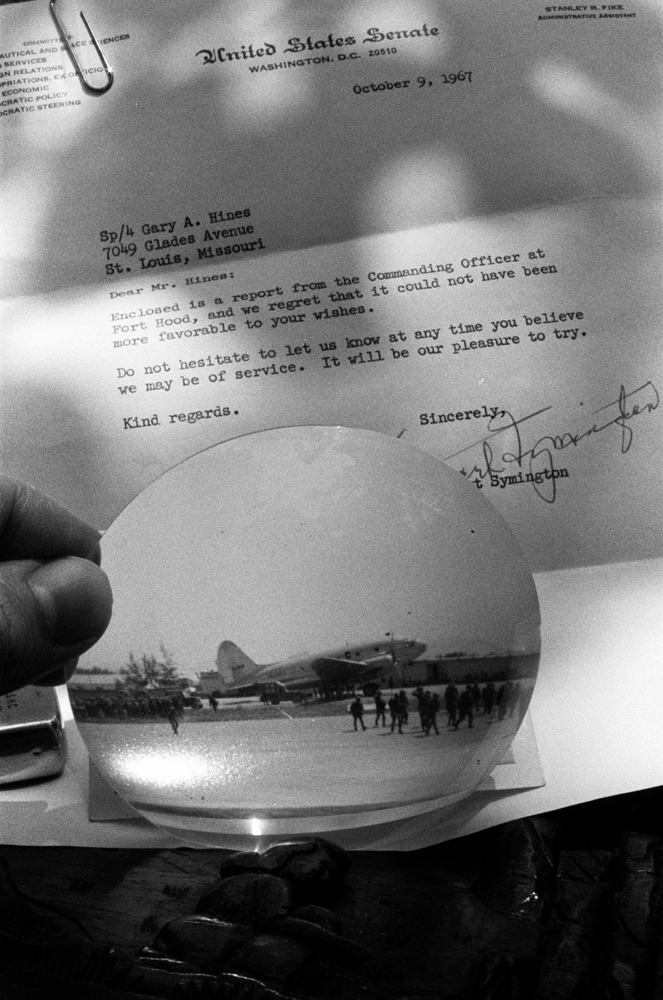

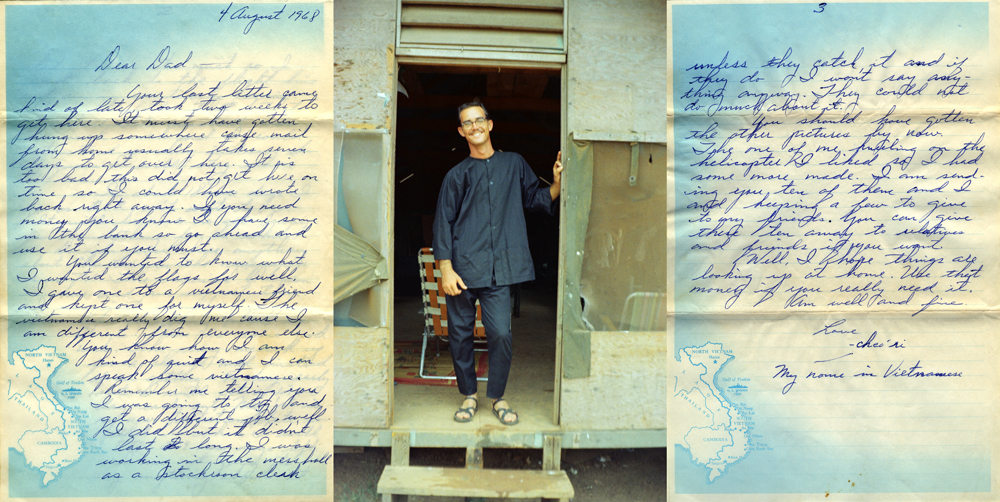

"In 1967 my brother, Gary, a soldier in the U.S. Army was sent to the American war in Viet Nam. Because our parents were not well and Gary was our caretaker, he made a request to Senator Stuart Symington seeking his help to avoid the order. A letter arrived on October 9th 1967, informing him “we regret that it could not have been more favorable to your wishes". He was instructed by the Commanding Officer to report to the United States Army Overseas Replacement Station in Fort Lewis, Washington for further assignment overseas. On November 4th, my brother arrived in Qui Nhon, Viet Nam. It was my eighth birthday. Because my parents could not care for me, I was sent to live with various relatives until I was in my teens. When my brother and I said our “good-byes” it would be the last time we saw one another for years.

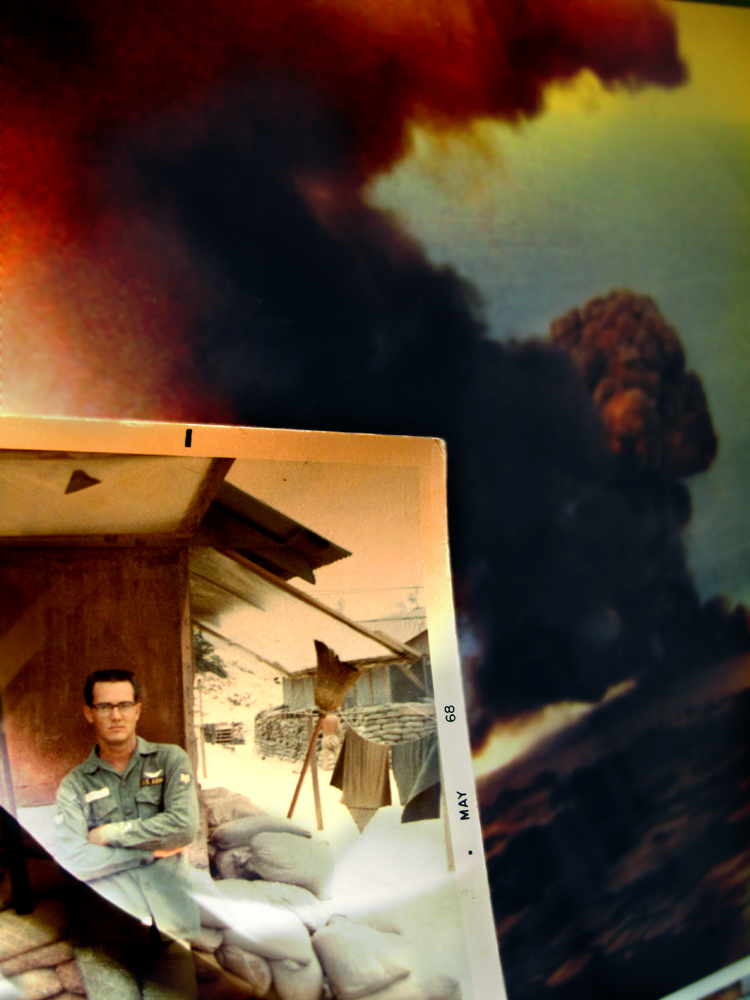

Gary wrote many letters home while he was stationed in Viet Nam. Pictures arrived. Although he wrote about his living conditions and told us about his work experiences on board the helicopters he rode into the front lines, not wanting to worry us, he rarely discussed the dangers he faced.

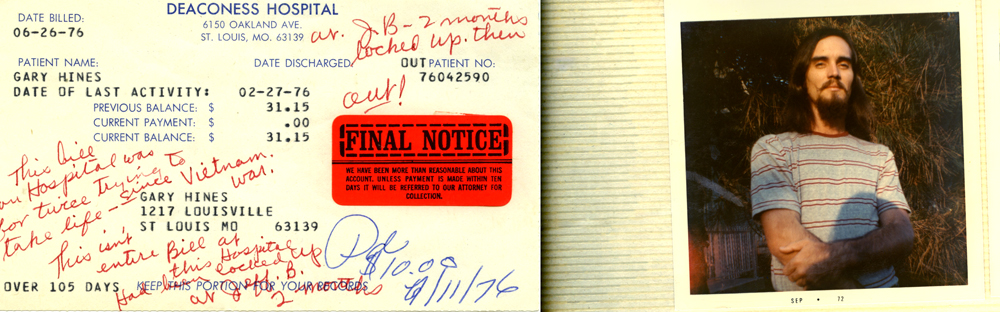

Honorably discharged from the army in 1969 with a “service connected nervous condition”, we later came to know his problem as Post Traumatic Stress Disorder. My pre-war brother, a normal and well-adjusted person had become, according to the US Veterans Administration, 50% disabled. He took his own life about ten years later." _ Jessica Hines

My Brother's War is a body of work in ten chapters. Each chapter follows Hines journey as she struggles to understand her older brothers life and death. This journey began with the desire to understand events in their lives and unfolded as a cautionary tale for everyone about the warlike nature of humans and the toll that war takes on individuals, society, and ultimately any possibility for peace on the planet.

HG: Your series, “My Brother’s War” is especially poignant today while our country is engaged in the longest sustained military conflicts in our history. Thus affecting so many American families. I wonder how you view these conflicts in light of your work?

JH: The word that comes to mind is “overwhelmed”. I’m overwhelmed at the sheer volume of loss experienced by the population. Having experienced life in the aftermath of war with regard to the loss of my brother, I can relate very easily to the pain of others who are also grieving. I am horrified by human aggression and by the motivation behind most wars.

Yes, American families are deeply affected by war and the ramifications of this situation reverberate throughout our society in ways that are, on the surface, invisible. But the effects are here. We may not realize that when we are in traffic, for example, and we see a driver suddenly behaving erratically -- that person might be a veteran with Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder who has recently returned from war. Consider also the person standing next to us in line at the grocery store who suddenly loses control and erupts into rage, or the policeman who suffers from Post-Traumatic Stress and has a flashback while making an arrest, overreacts, killing a civilian. So one result of war is the violence brought home. Domestic violence is also an issue. And sometimes the pain turns inward to result in alcoholism, drug use, and suicide – escape routes for veterans who are understandably unable to cope with their grief. Collectively, I am not sure that our country understands the affecting long-term results of war on our society.

What I find important to the understanding of my work is that the pain and personal destruction from wartime is a human phenomenon and that our focus should be on suffering humanity with a desire to understand our warlike nature and to instead love peace. My wish is that we are able to shift our awareness from our immediate surroundings to the global phenomenon that war truly is. In titling my work, “My Brother’s War” my intent was to make reference to “my brother” in the larger sense – in the sense of humanity at large. Geographic locality should not be an issue.

HG: What were your thoughts and ideas at the beginning of the work?

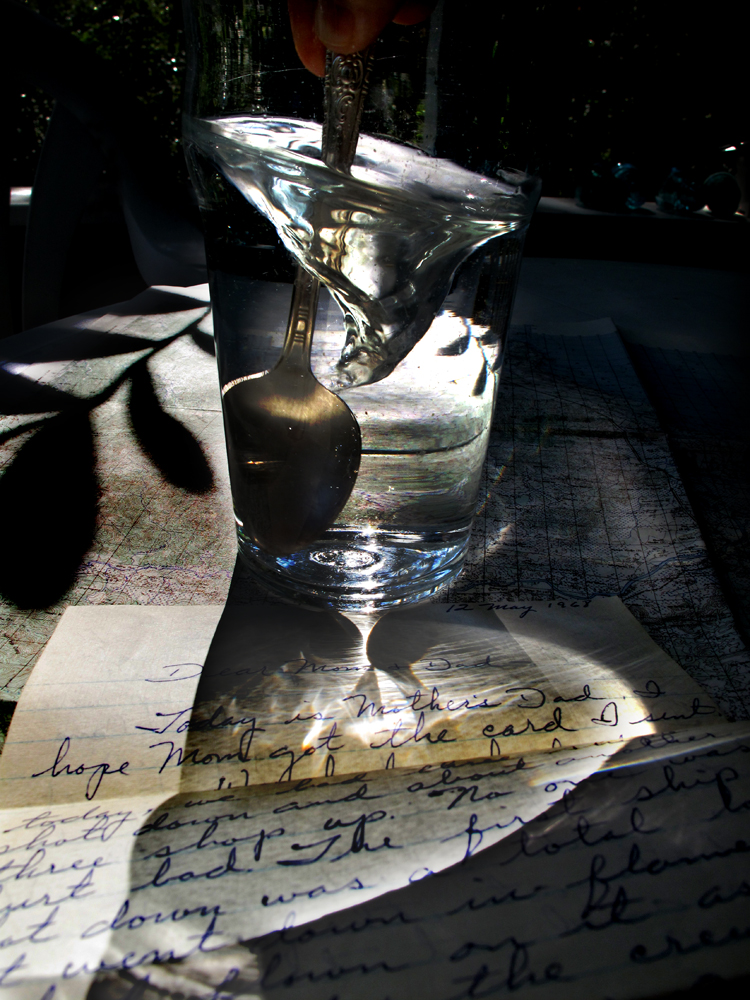

JH: When I first began this work, I had no idea how far I would eventually go with it. I had no idea that I would become as deeply involved in the story and investigate it to the degree that I have and for as many years. Odds are, I would never have made the work had a friend not asked to borrow Gary’s letters from wartime for a political science class in order to allow the students to read them. When I reread the letters, I was transported back in time and began to relive some of the experiences in my mind’s eye that left me feeling the intense desire to make photographs about my internal experiences.

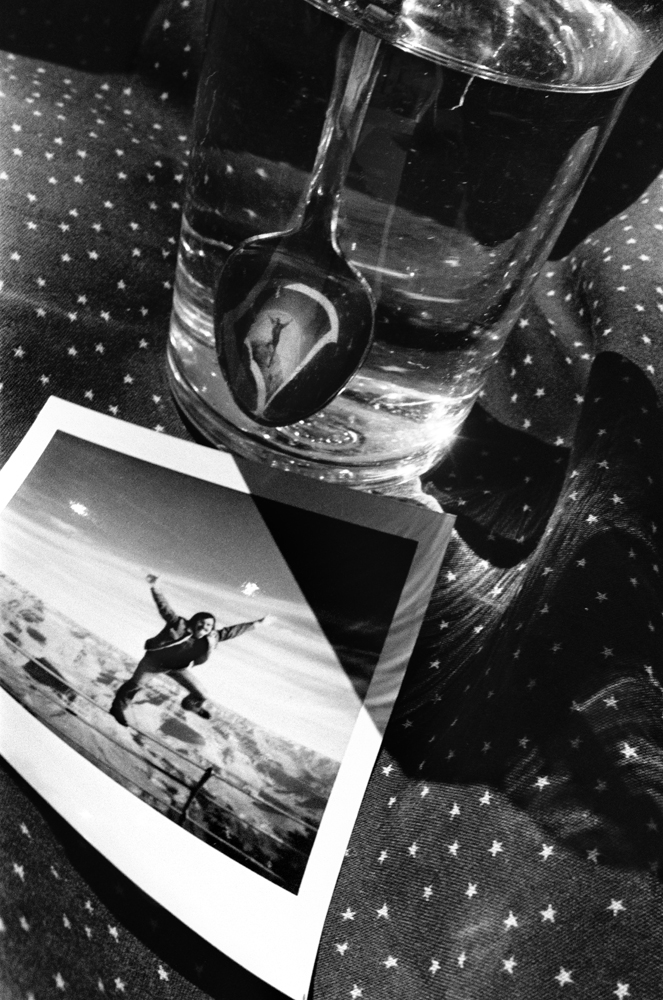

I began this work with black & white film and expected to finish the work fairly quickly. The early work was also begun from the perspective of my child-mind because it was my childhood self who I was in touch with while reading Gary’s letters. I was a small child when he arrived in Viet Nam and for all the years that followed during which he was involved in the war, his move later to Viet Nam to live as a civilian, and his return to the U.S. to live in the Colorado mountains in order to escape the pressures of society – these were all witnessed by the child-mind so it seemed to be the logical place to begin. My motivation was a strong desire to understand what had happened to Gary in wartime and understand what led him to take his life so many years later, to uncover deep mysteries about the brother I never really got to know in life.

In the early process of making this work, I did not realize how much material I would eventually uncover nor did I realize the extent to which the project would gain prominence in my life.

HG: How did they change after this journey with your brother’s memories and your travels?

JH: Straightaway, I changed from black & white film to digital as it made far more sense for me to do so when traveling to a faraway destination like Viet Nam where I was sure to encounter the unexpected and I knew that I would be traveling in intense heat. Shooting digital images that could be seen immediately and shooting in color changed my mindset as would be experienced by a musician changing guitars. Secondly, seeing the physical place that had framed my brother’s experiences was monumental. I finally saw, on two separate trips, the place I’d heard about since childhood that had gained, in my mind, a mystical status. To finally see Chu Lai was quite an emotional experience and doing so had a profound healing effect on me. Seeing the place helped me better understand Gary’s experience. I had a new frame of reference.

HG: Tell me about the layering, hiding and revealing that is seen throughout the work?

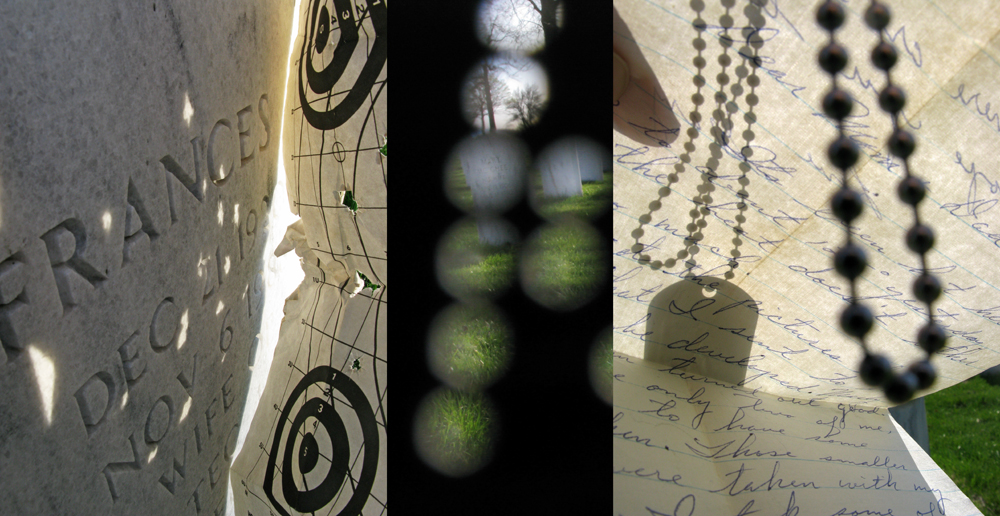

JH: As photography generally deals with the seen world and because I make photographs about what cannot be seen with the eye, it remains a challenge for me to successfully convey, by use of the camera, feelings, memory, dreams, imagination, and a world that has passed into the past. The work makes reference to people and places that no longer exist. In order to convey emotion and avoid the literal, I create images in camera by using old family photographs, Gary’s photographs from Viet Nam and his letters, combined with my own photographic vision. The layering, hiding and revealing are used to express what has been my own experience of this long-time learning process of revealing what has remained hidden from my awareness for decades.

HG: Such a small percentage of American families are touched personally by war. How do we as a nation do a better job in understanding the sacrifices of these families?

JH: About 13% of living U.S. adults are veterans. I think it’s a sizeable number when one considers all the people veterans come into contact with. I don’t mean to imply that every person who has served in the military during wartime will return home irreparably damaged but an unquestionable number of people do return home with serious injuries. Of course, the immediate families will experience the full force of the emotional state brought home but anyone who comes into contact with the veteran may encounter some degree of the sensation of that experience.

What venue about understanding veterans’ sacrifices and emotional health would reach the majority of the population? Aside from public programs and workshops, I’m going to guess that it is television and movies that have the ability to reach deeply inside the public consciousness to reach millions. Movies have a long track record of affecting public behavior so this would be a good place to start. American movies have a history of creating the macho hero who goes to battle against evil so we are also living inside a society that has grown up on movies and games that promote the idea of the war hero. It is my wish that instead, we promoted the peace hero.

Aside from patriotism, many of our current veterans are those who felt they did not have other career choices or other means of survival that signing with the military provided. But we are a warlike people. The U.S. has been at war for 93% of the time that it has existed.

HG: What advice do you have for other family members taking on a similar journey?

JH: This is a tough question. What comes to mind is Tolstoy’s, “Happy families are all alike; every unhappy family is unhappy in its own way.” I suppose that the coping mechanisms will be different. I will suggest this: attempt to understand that the person experiencing Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder is suffering from a traumatic injury -- and attempt not to judge that behavior. Because this disorder affects behavior, it is an especially cruel disorder. Being patient with the sufferer will be of immense help. Encourage the person to seek therapy.

HG: What are your dreams and hopes for the work?

JH: I hope first to finally publish a book with a good publisher that has excellent distribution. It is important to me that the work reaches a broad audience worldwide where it can be most helpful. Sadly, I think that many more wars loom on the horizon. While this is my brother’s personal story as well as my own, I think of this story as a universal one. My hope is that others will relate to it.

I needed to understand what happened to Gary -- this big brother whom I idolized but through odd circumstances, never got to know very well. I did find much of what I sought, indeed I tracked down many of his wartime friends by calling all people with the same names in the United States, I tracked down people I knew who were close to him, and I researched details about his life through his letters, through meeting men from his company in Viet Nam, though visiting Viet Nam twice, through finding his gravesite, locating he house where he died, I learned more details from papers saved by our mother, and it was also in small details that I was able to paint the picture of understanding of this life that eventually became so unraveled.

In my dream of dreams, I hope that a film will be made of this story. My deep hope is that by creating this work, I can help someone else’s grief, help someone else heal, help someone else to avoid the problems I encountered. I hope that a story(ies) like this, can serve as a cautionary tale, one that prompts us to take steps to avoid going to war in the first place.

Through the time period of working on this project, I too, unexpectedly, developed Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder and now I have an added insight into Gary’s condition. I hope that through all of this effort, others can see the extent to which war brings on suffering that lasts a lifetime. The pain never really goes away. I hope that others can see with wisdom and prevent the great pain caused when someone at the top says, “let’s go to war.”

HG: Thank you.

All images © Jessica Hines