Q&A: Joseph Liatela & Dorothy Santos

By Roula Seikaly | February 1, 2018

Joseph Liatela is an independent multimedia artist based in Los Angeles, California working in printmaking, performance, and video. His work explores the way we perceive gender, sexuality, the body, memory, trans/queer intergenerational connection, and the self.

Dorothy R. Santos (b. 1978) is a Filipina American writer, editor, curator, and educator whose research interests include digital art, activism, computational media, and biotechnology. Born and raised in San Francisco, California, she holds Bachelor’s degrees in Philosophy and Psychology from the University of San Francisco and received her Master’s degree in Visual and Critical Studies at the California College of the Arts. She is a doctoral candidate in Film and Digital Media at the University of California, Santa Cruz as a Eugene V. Cota-Robles Fellow.

Joseph Liatela and Dorothy Santos on Surface Tension at Center for Sex & Culture

In late January 2017, San Francisco-based curator Dorothy R. Santos witnessed a performance by multimedia artist Joseph Liatela at the opening reception for We’re Still Working: The Art of Sex Work at SOMArts Cultural Center. Moved by what she had seen, Santos immediately approached Liatela about a possible collaboration.

That first dialogue lead to additional conversations about visibility, surveillance, and how identity that rejects oppressive binary definition may be portrayed in contemporary art. Open through February 16 at the Center for Sex & Culture, Surface Tension—Liatela’s first solo exhibition—represents his year-long collaboration with Santos, and visualizes a potent personal transformation.

Roula Seikaly: Could you describe how your collaboration started?

Joseph Liatela: We met at SOMArts where I was doing a performance for the exhibition We're Still Working: The Art of Sex Work. Dorothy came up to me after the performance and expressed interest in working with me. We exchanged information and planned out this show starting about a year ago.

RS: Why does the Center for Sex & Culture (CSC) make sense as the site for this exhibition?

Dorothy Santos: It's place where I've worked before. I curated a twentieth anniversary exhibition honoring Watermelon Woman with Melorra and Melonie Green and the second show I curated was for Dorian Katz, another brilliant artist.

The reason why it made sense to stage Joseph's work here is because the Center is a place where people can learn a lot through the archive that is housed here. I wanted to situate it in a critical context, and the archive helps shape that context. It influences contemporaneous conversations about trans bodies. Joseph's work is so open, and not at all preachy about what audiences can learn about the subject. It was a pleasure to see what was a BFA thesis project evolve into something so beautifully realized. Also, CSC is a multi-use space. It's not a typical gallery or museum. The fact that so many eyes and ears representing a spectrum of identities may see this is really appealing. This work needs to be exhibited here.

JL: I think CSC has been a beacon in San Francisco in terms of queer identity, sex positivity, the history of the city itself, and that's important. Staging my work in this space amidst all of this archival material and creating an opportunity for viewers to be active and engaged in multiple ways if they choose to is really important.

RS: Tell me about the title "Surface Tension" and how the work came to be.

JL: So, I'll start with the technical details first. The image series Surface Tension I-IV includes photographs that were printed on silk and organza. I used medical sutures and sometimes my hair to combine the materials. As the sequence progresses, the top layer become more transparent. I've been thinking about surface in general, but particularly bodyscapes, and how a change in that bodily surface can completely change your existence. I think about bodies in public space and how they behave. I also think about surface in terms of projection. The video Artful Concealment and Strategic Visibility takes up notions of visibility and projection relating to gender: who is read as acceptable or correct in terms of their bodies.

RS: It sounds like you were thinking about all of these concerns before and during transition, and that the concerns you identified take on even more importance after the initial change. You run a wide and uncertain personal and professional gamut with this work, and present it with great subtlety.

RS: I'm thinking about textiles and how, historically, that work is associated with women's creative practices. Did that factor in your process?

JL: Absolutely. Thinking about the gendering of material was definitely part of my process. I studied with Angela Hennessy at California College of the Arts (CCA), and she talks about how a painting on canvas would never be called "textile," it would be called a "painting." How materials are gendered delegitimize the work women do in that context. I wouldn't say my work is about that, but I definitely considered that aspect in addition to notions of transparency and legibility.

DS: I'd add, building on transparency or legibility, that Joseph's work is not didactic. I think about something my friends in the CCA MFA program related to me, which is that Doug Hall would advise them not to make "academic essay art." What I mean by that is don't make are that is so heavily theorized that people can't find it accessible. There's a fine line between making work that is highly critical and sophisticated - though I that word suggests elitism - but it's hard to produce work at that level that is also relatable to wide audiences.

In Joseph's work, I see something that speaks to me even though going through transition or living in a trans body isn't my experience. The work conveys something I talked about in a lecture I gave in Berlin last year, and the metaphor may be a violent one, but it's like a hammer wrapped in velvet. This elegant work conveys a powerful message.

RS: Before you arrived, I looked at the four-piece sequence Surface Tension I-IV and noted the sutures that bind the organza to the silk. That imagery could suggest violence, for lack of a better word. Could you speak about that aspect of rupture or tactile violation?

JL: There is an experience of violence when undergoing surgery, that's for sure. But that's not what the piece is about. It has more to do with the personal violence of body dysphoria and erasure. I didn't want to be overly reverent to the material, which means that the sutures aren't linear or neat. Our bodies aren't linear or neat.

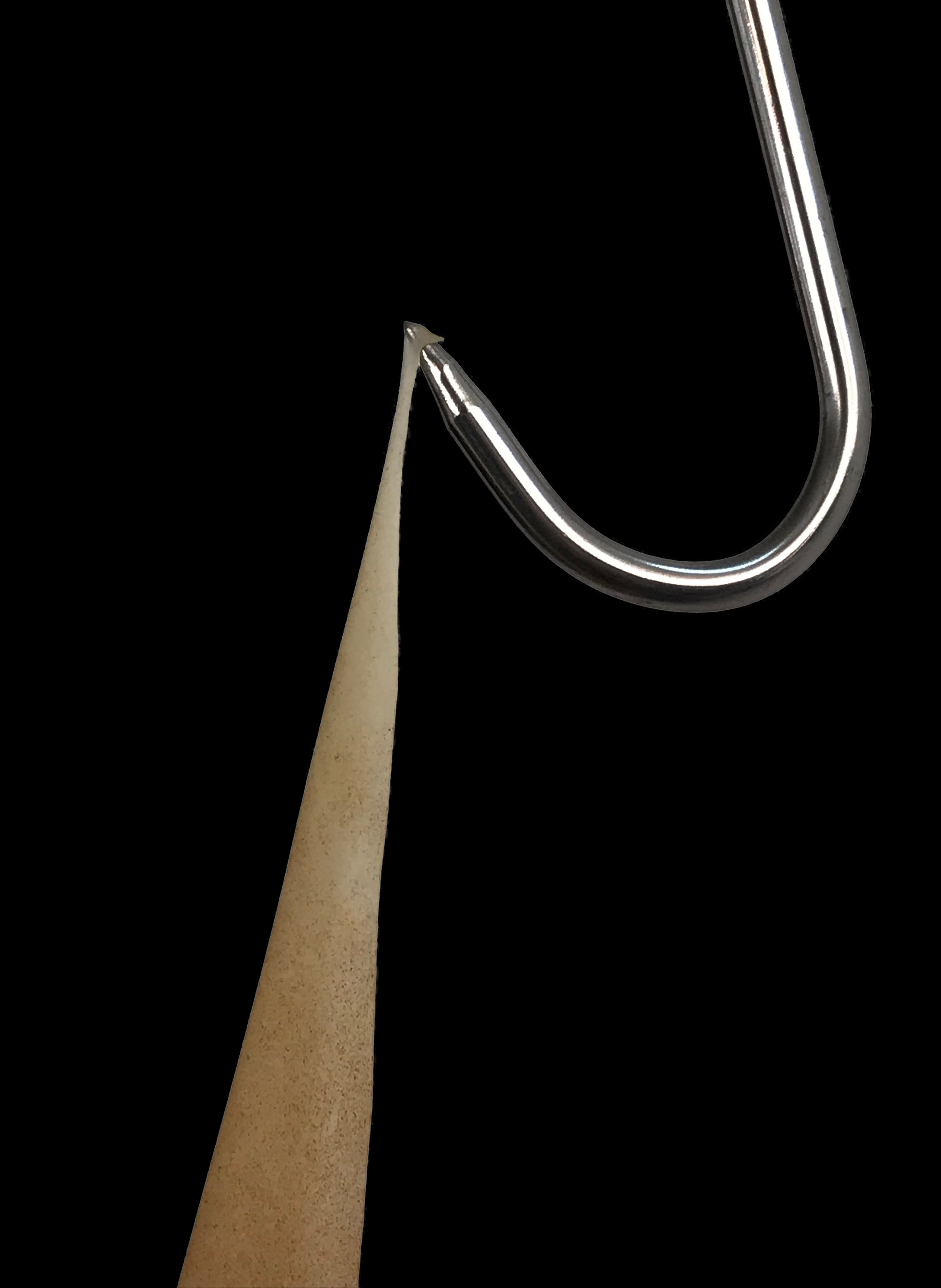

DS: There are two things that came to mind that I would add, which are totally tangential but slightly connected. I saw Claudia Rankine speak in 2015, and she talked about her book Citizen. I think when people read it, the primary subject is violence against black bodies. She said that the book was originally meant to be about intimacy, and it turned into a book about violence. Why I mention that now, and what I gleaned from her talk, is that violence and intimacy are intertwined. It's not necessarily a negative connotation. Cloaked, for example, embodies that tension. The literal tension the piece communicates: the steel hook, something that's hard and pointed, and associations with flesh or meat. A "meat hook," if you will. There's a violence in that, and this will sound strange, but the hook and all the violence it suggests is also the thing that nurtures us, if one eats meat. That's not what this work about, but what it evokes is so dimensional. The work isn't easy consumed. It makes us think, and that's powerful against a foil of hyper visualized, easily consumed culture.

RS: The subject of trans lives has been elevated in the media in the best and worst of ways, such as Danica Roem's election victory or North Carolina's bathroom bill. It forces us to confront strict gender binarism and definitions of identity. I'm wondering about what it means for you to be seen as a whole person, as opposed to transparent, and how you want to be seen. Is that something you're responding to in the work?

JL: I think I'm responding to the impossibility of being seen. I'm incredibly thankful for access to the medical procedures and treatment that make this a reality for me, but I think there's still a schism. I don't necessarily identify as a man, though that's how people read me now, and that's a very privileged position to be in. I don't feel like a different person, but how I exist in public space and how I'm seen has changed completely. It takes time and nuance to see anyone, to see and appreciate the conflicting truths they embody. When my body is looked at now, it's a closer proximity to me, but for myself as a trans person who now passes it's really complicated.

RS: Do you feel like you have to explain your process, and that can mean your creative practice or your transition experience, or both? I know that many trans people bear a burdensome expectation to explain who they are that cis-identified people don't face. What do you think about that?

JL: I think every artist of marginalized identity has to grapple with this unfortunately. I don't feel a need to explain myself to audiences, but I do feel strongly about creating work that has a variety of entry points for viewers and to be receptive to what people do or don't take away from my work. I want to live in a world where trans people can make art that isn't about their experience. I would be missing out on so much if I was closed off to people who may not be familiar with these issues. Of course, I'm intentional about what I want people to see, but I would be doing myself a disservice if I wasn't open to hearing other interpretations of it.

Photos above by Kimberley Acebo Arteche

Photos above by Joseph Liatela