Q&A: Julie Weber

By Jess T. Dugan | July 9, 2020

Julie Weber is an artist and educator based in Chicago, IL. Working conceptually within the framework of photography, Weber is interested in the medium as subject matter through exploration of photographic materiality and process. Recent solo exhibitions include re|process at The Alice Wilds (Milwaukee, WI) and re|materialize at Seerveld Gallery (Palos Heights, IL). She received a BA from Dominican University (2006) and earned her MFA in Photography from Columbia College Chicago (2014).

Jess T. Dugan: Hello Julie! Thank you so much for taking the time to speak with me today. Let’s start at the beginning – what initially drew you to working with photography, and what was your path to getting to where you are today?

Julie Weber: Hey Jess, thanks for having me! Early on in my high school years, the magic of the darkroom captivated me and inspired me to get a job at a one-hour photo lab, a job I maintained for nearly a decade. When it came time to visit colleges, I remember adamantly considering schools only if they had a darkroom – which looking back now, clearly spoke volumes – even though pursuing art as a major, let alone a career, never really crossed my mind. So I minored in photography but majored in psychology and sociology with a particular focus on research methods. I worked in cognitive drug research for a few years out of undergrad, from which I got some major life experience living abroad and traveling. Everything about that experience made me believe more deeply in the power and importance of art to the point that I decided to navigate a career change, which the short of it, led me to grad school at Columbia College Chicago in 2011 (where we met!) and is when I’d say my career as an artist formally began. Since then I’ve been working in Chicago as an artist and photo educator.

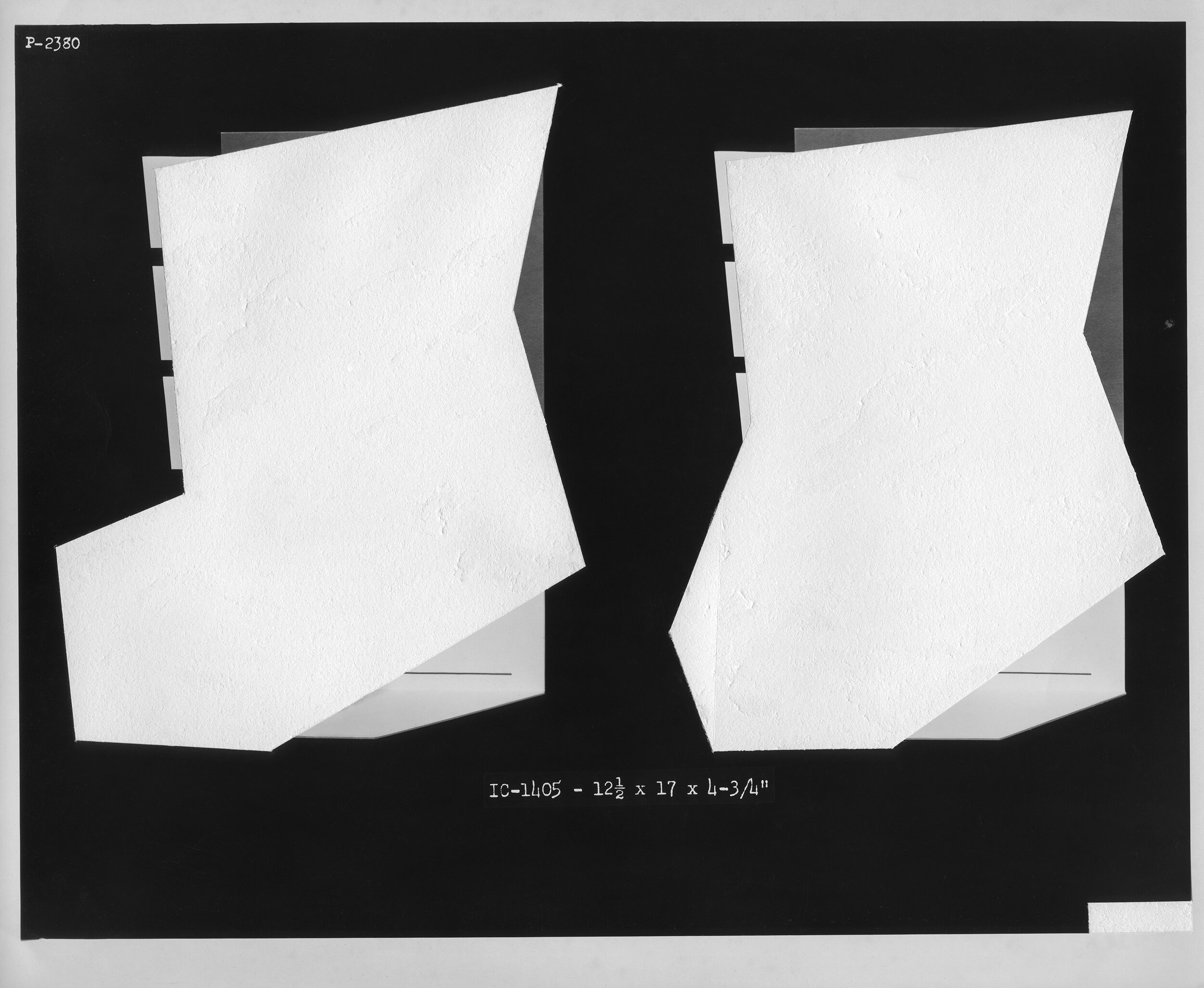

Undisclosed Typology 1403.04.K, 2014

JTD: Much of your work is cameraless, exploring the physicality of photographic materials and their interactions with light. Talk to me more about this – how did you begin working in this way?

JW: There are definitely aspects of natural inclination and inquisitiveness that drive me, but undoubtedly, my background in research psychology influences my approach to making, which is concerned with experimentation, methodology, and illustrating process. I consider myself a researcher and photography my subject. Much of the conversation in photography centers on camera, image, and representational depiction. Early on, I knew I wanted to be part of a different conversation. By eliminating the camera and the traditional image in my own work, I was able to focus on the photograph as object, which in turn led me to concentrate on photographic materials – light, paper, emulsion, chemistry, found prints, printer ribbons, etc.

JTD: It seems that most artists have an underlying question and/or interest that drives their work, even if they come at it from various angles and directions. What would you describe as the core interest that motivates and inspires your work?

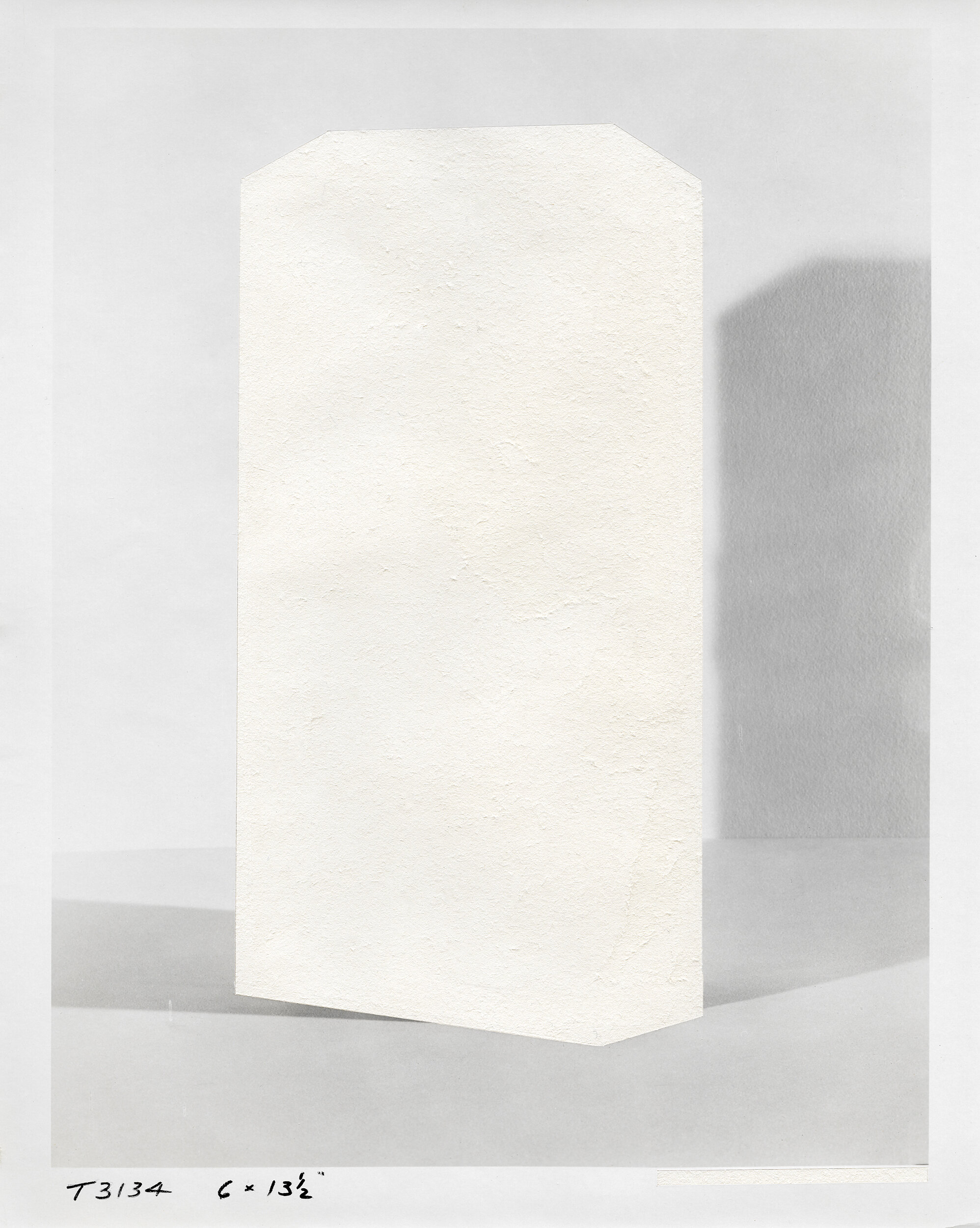

JW: At the core, I’m always asking, “What constitutes a photographic image?” I’m not asking, “What is an image?” or “Does the work I make qualify as an image?” It’s not a matter of definitions – it’s a matter of process. By exploring the material components of image making and the inherent properties of those components, I can tinker with the process and experiment with alternative or unconventional potentials. Photographic paper has an intended use in the darkroom to yield a fixed outcome; so why not use photographic paper in an unintended way outside the darkroom that yields a changeable outcome? I am oversimplifying here, but hopefully the gist is coming across – there is usually a sort of ‘yes this but what about that?’ approach that gets me initially experimenting with a material. And then something that often guides that experimentation is considering how I can use the materials to yield images that depict the process they undergo.

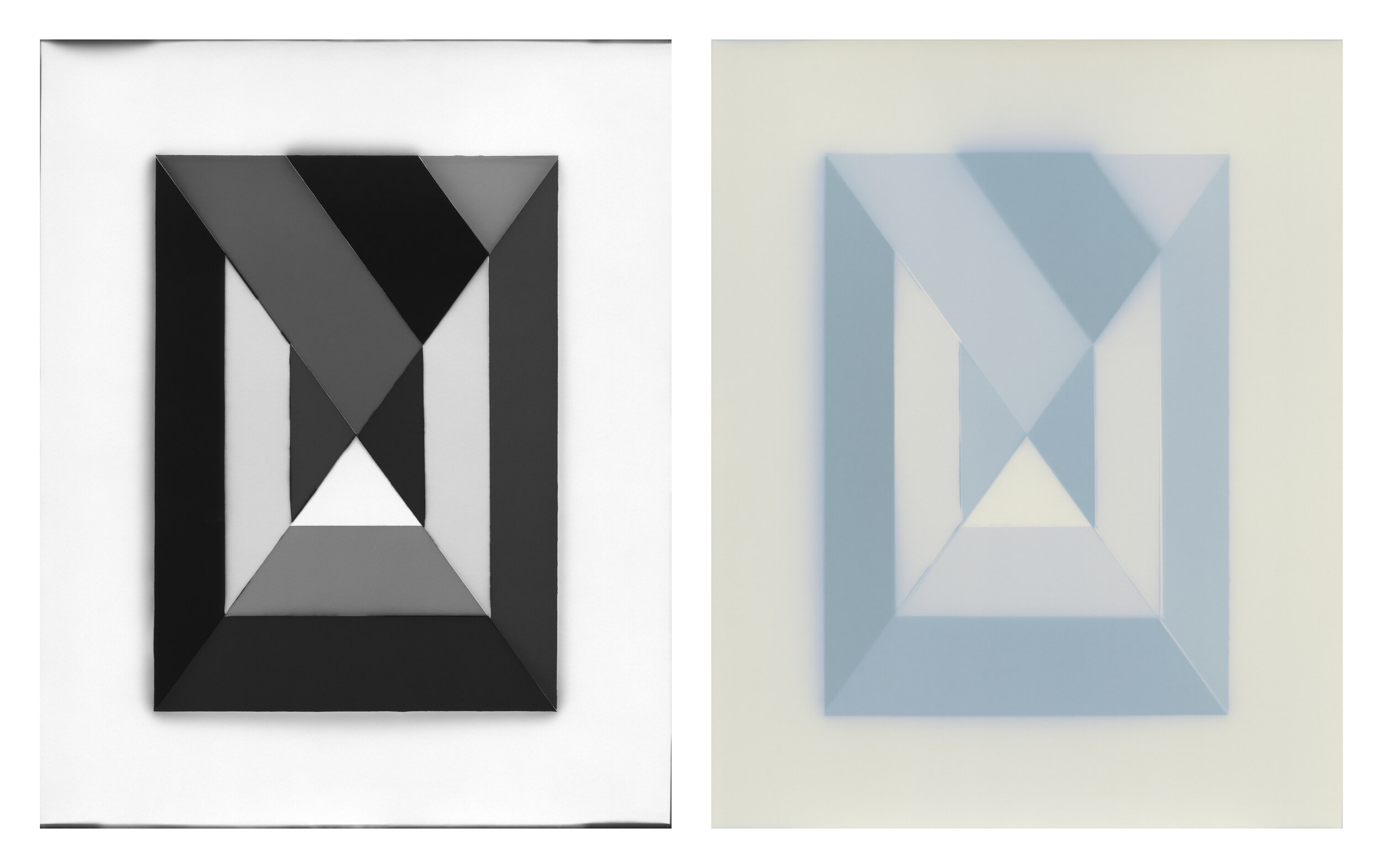

Image #5 in YM (portraits), 2019

JTD: I love that you talked about being a researcher whose subject is photography. Much of your work is methodical, requiring you to spend many careful (and often meticulous) hours in the studio or darkroom. Talk to me about your working process – I can imagine your experience of making can be both meditative and also sometimes tedious, depending on where you are in a series and what is required of the particular piece you’re working on.

JW: Overall, I’d describe my working process as cyclical. It starts with research, planning, and gathering of materials. Then there will be a flurry of experiments followed by a need to step back and examine all the results, to learn from the materials in order to decide which directions to move forward. More experimenting and more examining, repeat, often until a final method is decided. It’s very iterative in its repetition and I find that to be meditative, particularly when I hit a stride, but never tedious. If I do start to feel that what I am doing is becoming tedious, then that’s a good signal to reevaluate and change direction. I often joke about how studying photographic papers change color or peeling emulsion from photographs is like watching paint dry – but I genuinely enjoy it – if I didn’t, I wouldn’t be able to make the work that I do!

Descending Gradient (Ilford Multigrade FB), 2017

Perceived Transparency (Kodak Polycontrast III RC), 2017

JTD: That all makes sense. I’m interested in the idea of addition versus subtraction in your work. In some of your projects, such as Undisclosed Typologies, you remove a section of the photograph (generally the section containing the original “content”), leaving a geometric white space for the viewer’s imagination to fill in. In other projects, such as re|process and certainly your light sensitive work, you are adding elements through the layering of photographic materials or the presence of light itself on unfixed photographic paper, which of course changes the image over time. Can you talk to me more about these various methods – additive and subtractive – and how you think about them both conceptually and formally in your work?

JW: This is definitely something I consider regularly in my work and it is closely linked to how I think about the photograph as both an image and an object. With Undisclosed Typologies, I was working with found photographs. So I saw my starting point as a finished photograph that I needed to partially deconstruct in order to move away from the image as the dominant subject, and instead, emphasize its physical qualities as an object with a lived history. With the light sensitive work, I saw my starting point as a blank object, a sheet of photographic paper, from which I needed to partially construct an image. I see these two bodies of work arriving at a similar midpoint but starting from opposite ends – a sort of ‘separate ways together’ or ‘opposite sides of the same coin’. Photography is seemingly full of dualities – light and dark, still and moving, positive and negative, image and object, additive and subtractive, analog and digital, studium and punctum – and so on. However, I’ve always been interested in finding the sort of precarious midpoint of a spectrum and holding that tension – not thinking of these elements as oppositional but as facets of the same thing.

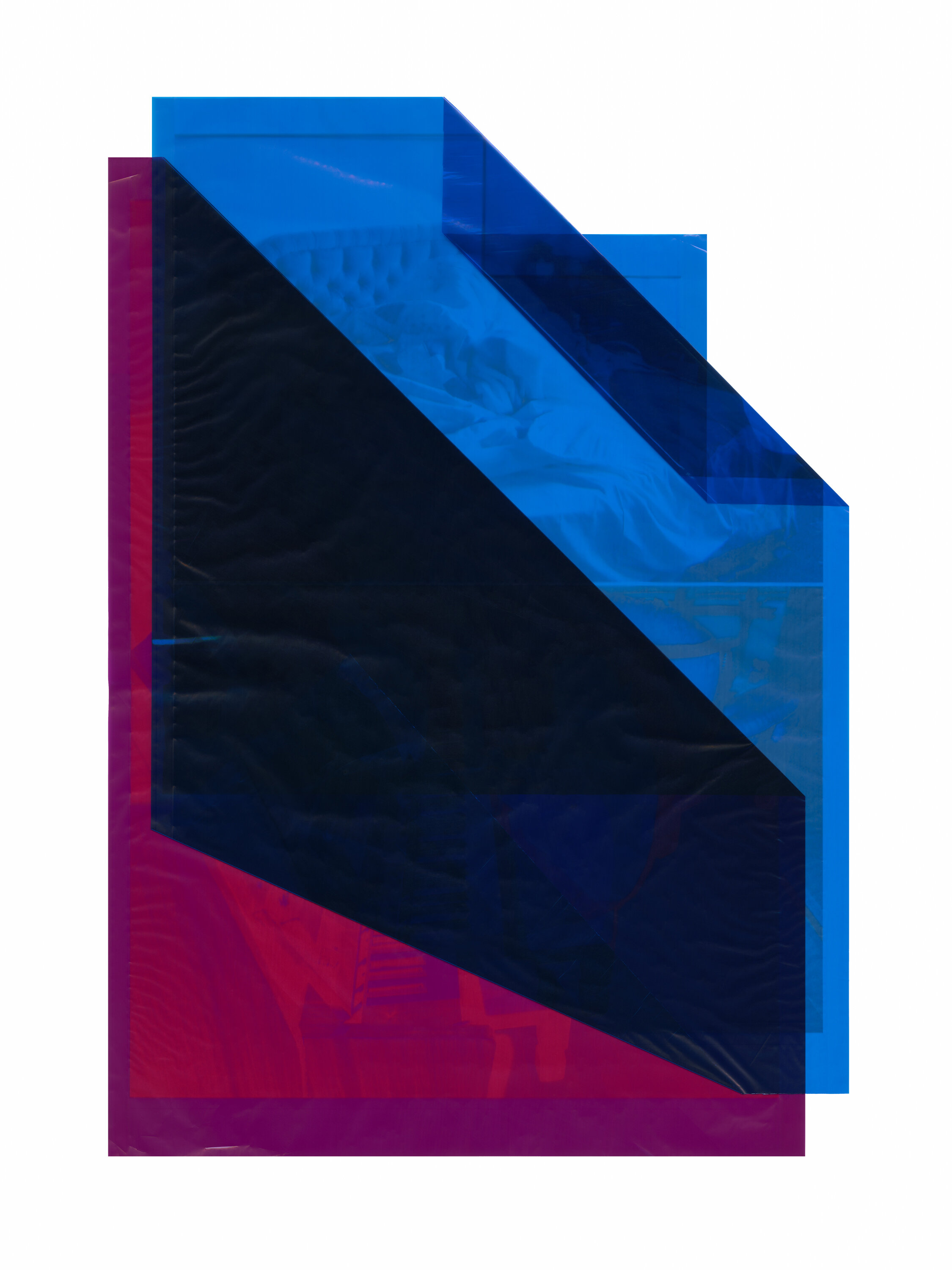

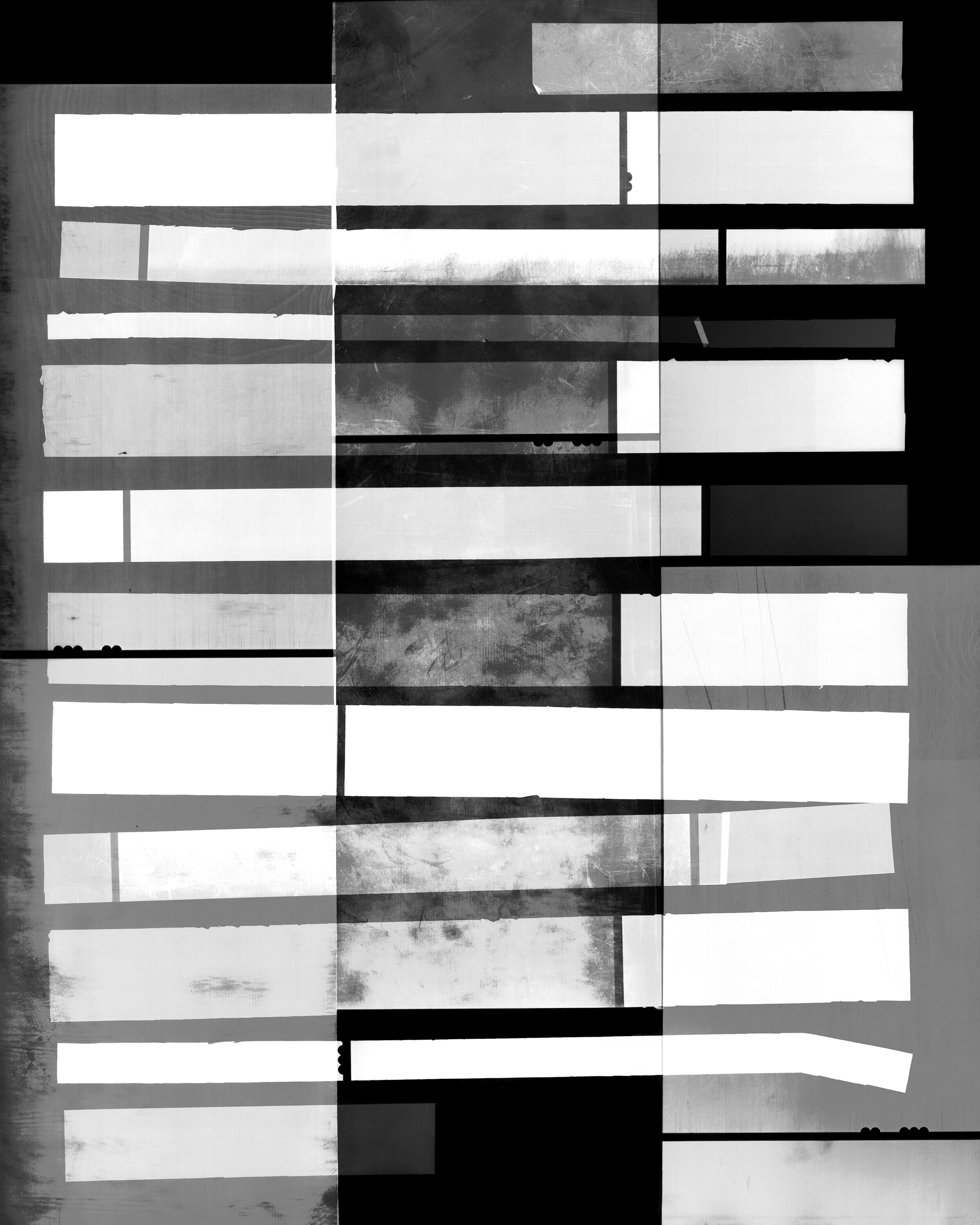

Offcuts #3 in CMY, 2019

re|process has been very different for me. The work is based in using a material that is neither blank, nor the finished product, but is a byproduct of digital lab printing. I began to see the image as an inherent characteristic of the material rather than a thing to construct or deconstruct. So I became more interested in the oscillation of weaving a physical byproduct of a digital process into other spaces such as digitization through scanning and contact printing in the darkroom. It feels very fluid to work with this material in both analog and digital spaces because that is the time period it comes from – when digital kiosks and printers first started showing up in one-hour photo labs – which is where I first learned of and collected the material from orders I processed on the job.

Image #1 YC in B&W (interiors), 2019

JTD: How do you see your work changing or evolving as we move further and further away from analog photography? Do you anticipate moving to work in a digital space, or are you interested exclusively in analog materials and processes?

JW: I’ve come to realize and appreciate that as an ‘80s baby, I am very much shaped by my lived experience of the cultural transition from analog to digital, and I think this has influenced my predilection for working with outmoded materials. As technologies advance, previous technologies are freed from their original purposes. The advent of photography unburdened painting in many ways and paved the way for abstract expressionism. I feel digital has allowed analog materials and processes to be reconsidered and repurposed. I don’t see myself as working exclusively with analog because digital is part of my language too – especially as demonstrated in re|process and a series called Luminaires, in which I made 8x10 digital negatives from digital capture that I then printed in the darkroom – the outcome appearing as traditional photograms. If I am using digital, it is always in combination with analog, so “Could I see myself ever going fully digital?”: at this point, I don’t see it happening, but you know, never say never!

Installation View, The Alice Wilds, Milwaukee, WI, 2019

JTD: What are you currently working on? What’s on the horizon for you as an artist?

JW: Spring and summer plans, including a couple of exhibits and a residency, were postponed due to the pandemic. Teaching in the fall is going to look different, so a lot of preparation is happening right now to accommodate remote learning, hybrid online/in-person schedules, and contingency plans. Despite circumstances, the art and music building at Waubonsee Community College, where I teach, is under renovation this summer, and I am beyond excited to get back into a fully remodeled darkroom at the end of summer.

Currently, I have a print available in Artists for Action, organized by The Alice Wilds and featuring over 20 artists from the gallery and community in support of the Black Lives Matter movement. 100% of the proceeds from this exhibition will be donated to organizations that have been selected by the artists to forward this movement. As a woman and a firm believer in the power of community to share, heal, liberate, and grow, I support The Loveland Foundation, which is a continuation of Rachel Cargle’s Therapy for Black Women and Girls fundraiser. I admire, respect, and look to Cargle as a leading voice of truth and vision. In the late summer, once I’m back in the darkroom, I will be running a limited edition print series to continue raising money for The Loveland Foundation.

Last fall, I exhibited re|process at The Alice Wilds in Milwaukee. I’ve been continuing to work with the dye-sublimation material and am looking forward to showing a new iteration of this body of work at Concordia College in Moorhead, MN this coming November. I’m also looking forward to a survey exhibit at Harper College in Palatine, IL next spring.

All things aside though, I’m just hoping to be able to see you and friends again at exhibits and events soon!

JTD: Me too! Thanks so much, Julie, and I look forward to seeing your new work.

All images © Julie Weber