Q&A: Lori NIx

By Jess T. Dugan | September 7, 2017

Lori Nix was born and raised in western Kansas, in an area known for its tornados, snow storms, droughts and infestations. As a child, she viewed these natural disasters as entertainment, relieving her of her otherwise ordinary reality. Brush fires and fallen trees became her playground and influenced her first body of work, Accidentally Kansas, for which she garnered much acclaim.

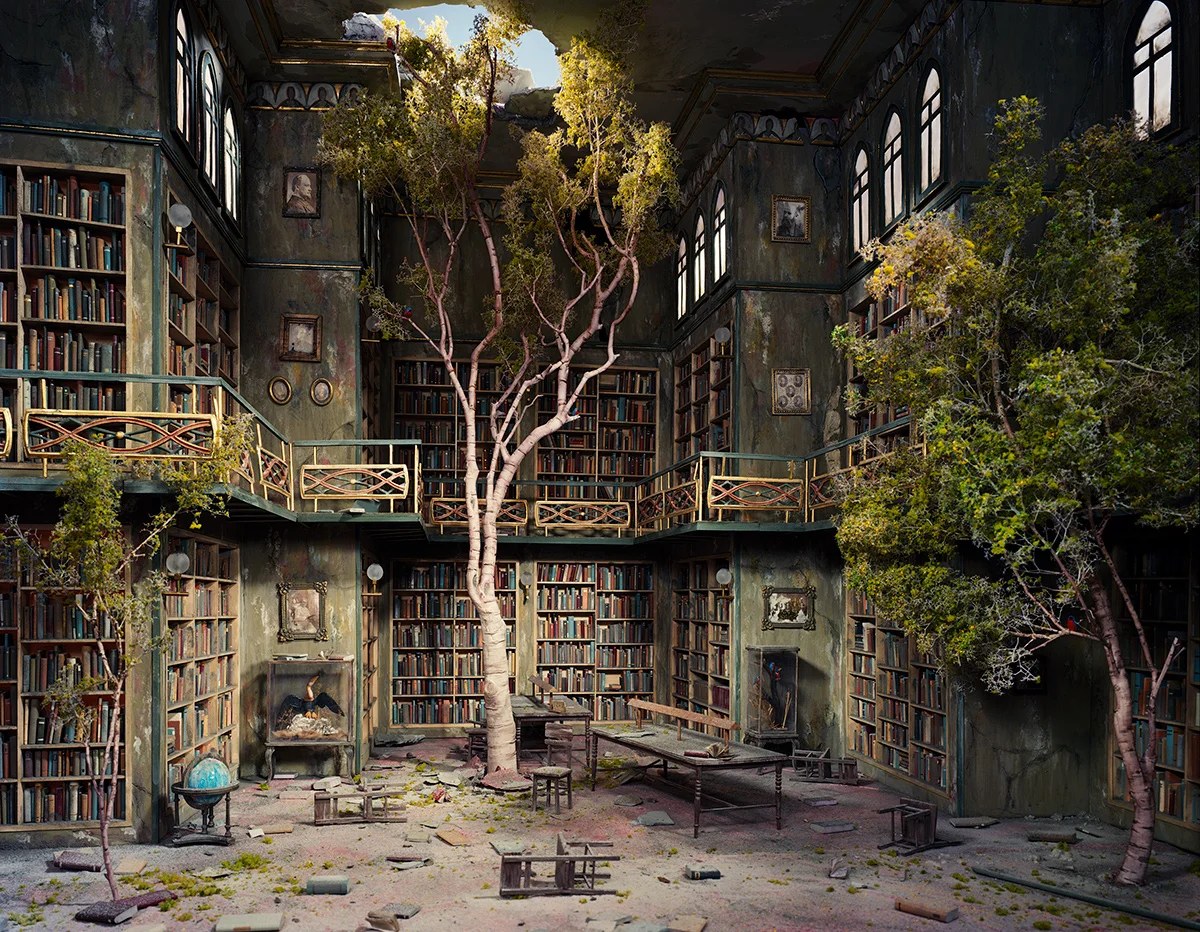

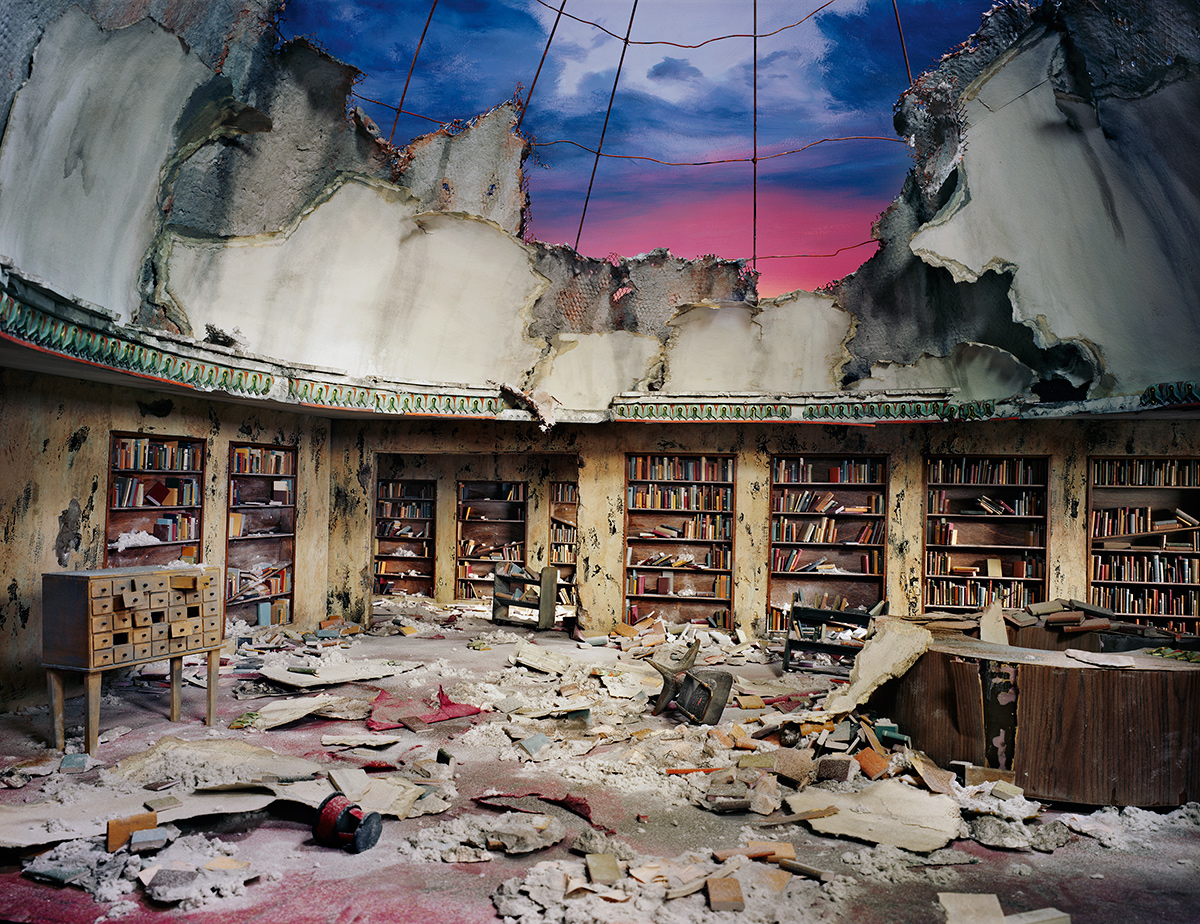

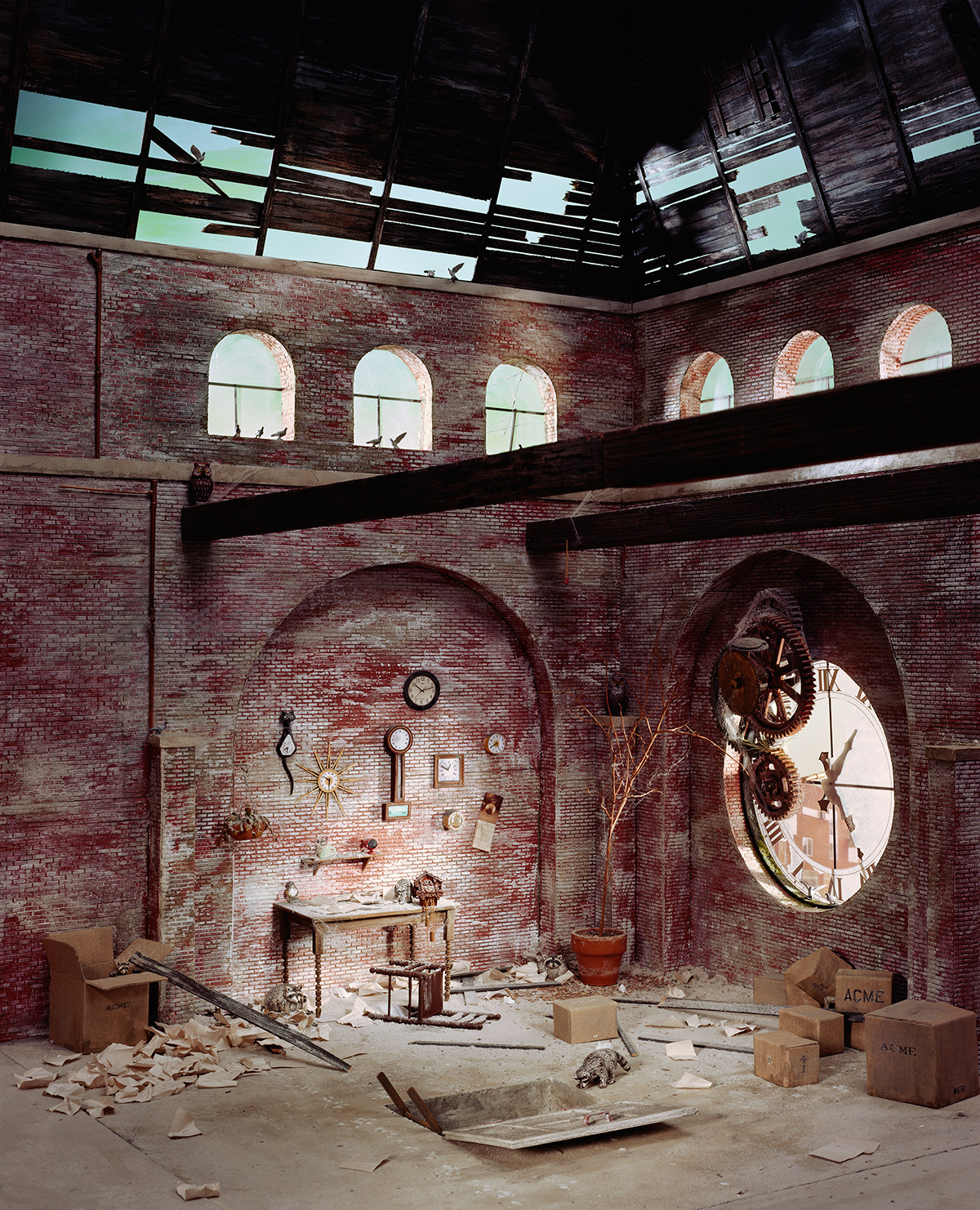

Working in her home/studio, Nix combines cardboard, foam, glue and paint to construct small dioramas which she then photographs with an 8 x 10” camera. Often taking up to seven months to complete, these large scale photographs of everyday places – a laundromat, bar, library, aquarium – fall victim to decay, referencing the effects of man. Using humor as her anchor, Nix’s work challenges our perceptions of reality, as she reminds us of our responsibilities.

Lori Nix has received many honors including a 2010 & 2004 New York Foundation for the Arts Individual Artist Grant. Her work has been exhibited throughout the country and is in the collection of the Museum of Fine Arts (Houston), The International Museum of Photography at George Eastman House (Rochester, NY) and the Smithsonian American Art Museum, Washington, DC, among others.

Jess T. Dugan: Hi Lori! Thank you so much for agreeing to speak with me. You are very well-known for your photographs of elaborately-constructed dioramas that depict scenes from a post-apocalyptic future after a disastrous event of some kind. As you say on your website: “For the last eight years my photographs have highlighted a fictional urban landscape ‘after’. An aquarium after a flood, a church after a fire, a beauty parlor after…who knows what. Mankind is gone and what remains are vacant fragments of buildings, a few slowly being reclaimed by nature.”

Because you have written extensively about the process behind your work, I’d like to tailor today’s interview to focus on your life as an artist and the conceptual elements behind your work rather than the process itself. To begin, I’m curious about your working space. I understand you work in your home, which is filled with dioramas and various objects that you use to make your photographs. How did you go about setting up your studio? Was it intentionally planned from the beginning or did it evolve organically over time?

Lori Nix: The studio situation has evolved over the past two years. For sixteen years, my apartment was the studio where the dioramas were constructed and then set up to be photographed. The apartment is really an eyesore these days. I call it my garage more than my apartment. Ninety percent of the space is dedicated to art production. There’s a chop saw sitting under the kitchen table, framed artworks line the hallway and the bedroom. The bathroom is where we keep most of the acrylic paints and some photo equipment. We only have one comfortable chair in the apartment, the rest are office chairs and a folding deck chair. I consider the back two rooms, which we call the spray room and the computer room as my production space. Kathleen does most of her work in the living room.

Subway

JTD: You collaborate with your partner, Kathleen, on your work. How does the process of collaborating, particularly with someone so close to you, affect your work and process?

LN: I spend the majority of my days in the back two rooms; Kathleen spends her days in the living room, so there are long stretches where I feel like I don’t see her much, even though we spend 24-7/365 days together.

Kathleen has been quietly involved in the art making since 1999. It’s only in the past few years that we’ve made a concerted effort to get her name mentioned along with mine. For many years she didn’t care to have her name as part of the artwork for several reasons; mostly because she felt I did all the photography part of the process, setting up lights, the camera work, printing and post production. We also had established a bit of a (and I really hate this word) brand LORI NIX while we were trying to get this art career off the ground. But as I’ve lectured about my work over the years, I’ve always let people know that I do not make these images by myself. There are two of us and at times three of us working on these.

I see my role as the architect and Kathleen’s role as the sculptor. I come up with the initial idea and do some research, then together we brainstorm all of the items we want to include in the scene. I design the physical space because I think like a camera; Kathleen does not, but she’s getting better. I come up with the color palette and shoot the scene. But I honestly believe it’s what Kathleen contributes that makes these scenes come alive.

Anatomy Classroom

Let’s dissect “Anatomy Classroom” to give you a better idea. I wanted the room to have an institutional blue/green that was the mainstay color of my academic childhood. I built the walls, cut the floor tiles, sculpted and assembled the desk chairs together and built all the cabinets. Kathleen sculpted all of the skulls (she had a lot of fun, some are alien skulls, child skulls, even a few with bullet holes). She also created all of the anatomy models that line the shelves, the specimen jars, the posters and the overhead projector. After the room is perfect, she then destroys it and adds layers of dust and water damage. I think she’s fearless.

It helps tremendously that we each bring something different to the project. I cannot do what she does, and she’s definitely not interested in the architectural part of the process, which is more about measuring and cutting. Our favorite tools are different, so we’re never fighting over them. And Kathleen’s approach to a problem may be completely different than my approach to the same problem; so solving problems is pretty efficient when two brains are working together.

Where we do diverge with the work is usually with the tone of the image. I want darkness, death and the macabre, Kathleen wants cute and hopeful. She keeps me from being too gross and I keep her from being too nice. Ironically, in life, I’m more of the optimist and she’s more of a pessimist, or as she says, a realist.

Library

JTD: What is a typical day like for you? Do you work for long, focused stretches of time or do you have to get up and leave the studio at some point?

LN: These days I roll out of bed around 7:30am because this is when our cat decides it’s time to wake me up. Both of us putter around the apartment, catching up on email and social media, and sometimes go for a walk in the park when the weather is nice. We get started around 10:30am and work until 10pm at night. There are days I don’t even leave the apartment. I work alone, often times plugged into my iPod or listening to the radio. We see each other at meal times or when I need her opinion on something.

JTD: Your work has so many elements within it- disaster, serenity, fear, humor- and doesn’t settle on a simple narrative or fall into predictable tropes. How do you assure that each piece remains complex and impossible to reduce to one simple idea or emotion? Is this inherent in your working process or is it something you do more consciously?

LN: It is definitely a conscious effort to make the scenes complex. Just the fact that we build or select every element makes it be a conscious decision. I see each of these images as narrative, a story to be told, and a good story takes a while to tell. I don’t want the image to be read quickly. I want the viewer to spend more than the average four seconds of viewing. So the longer one stays with the image, the more they will be rewarded. I try to address the image on several levels. The overall scene needs a good color scheme and interesting overall design. We then strive for well-made, thoughtful objects. And then there are sometimes personal or symbolic references which can add another layer of meaning - “Vacuum Showroom” has advertising posters on the wall that reference famous paintings.

Vacuum Showroom

There are often contradictory elements in the scene. We’ve been working the past three years on urban landscapes. The scenes are still full of destruction and abandoned buildings, but they are combined with lush vegetation and beautiful skies. I have a former professor’s voice in my head saying “reel them in with beauty and poetry, then hit them over the head with the idea.”

Arch

JTD: I love that you have a Q&A section on your website that addresses your influences and your process, as you regularly get questions about these topics. You write, “as a ‘non-traditional’ photographer (I construct my subject matter rather than go find it) people find it hard to grasp what exactly it is that I do.” There is certainly an assumption that photographs are “true” and have an indexical relationship to the world. How do you think your work complicates this assumption? And do you think that is part of why viewers might have a hard time understanding it?

LN: I do think the general public assumes that photographs are real, taken of real places and real events. We are taught that photographs are a record of something that exists. Most people are not accustomed to seeing “constructed” images out of the context of a fantastical postcard or funny poster. So, I’m always a little bit shocked when people ask me “where was this taken” because to me, these scenes do not look remotely real. The scale might be a little skewed, the colors too vivid. My kneejerk reaction is to assume people aren’t really looking very intently. But then our goal is to make these scenes look as real as possible. So if the viewer is confused, then possibly we’ve succeeded. Sometimes they figure out that it is not “real” and then they re-examine the image with a new perspective. Sometimes they don’t, and they walk on.

JTD: I’m always interested to hear how artists set up their lives in a way that facilitates their work while also finding a way to support themselves financially. You and Kathleen have a commercial branch of your practice called Nix+Gerber and make commissioned dioramas for a variety of commercial clients. At what point did you realize that you could turn something you were passionate about and very good at- building amazing dioramas- into a business? How do you find a balance between work for hire and your personal work? Do the two fuel or influence each other?

LN: We’ve been invited to work on commercial projects over the years for clients such as O Magazine, TIME, New York Magazine, etc. These last four years the projects have become bigger, more ambitious and involving video and film. We took the plunge and decided to pursue it full time. We traded in steady day jobs for more tumultuous but also more rewarding work. There are definitely hills and valleys to this line of work, but I don’t miss my daily subway commute at all. As far as balance, when we’re working on a commercial project, the art is put aside and all our energy goes into whatever job is in house. The commercial work doesn’t influence the content of the artwork, but we’re always trying out new materials and techniques, which we will apply to the artwork. I’m still trying to figure out how to make the most realistic fake tree. I’ve been at it for years and I’m still not satisfied.

Botanic Garden

Because of our side business of Nix + Gerber, it’s forced us to rent an outside studio. We’ve been active with the commercial work for years, but got serious about it in 2015. As we were working on commercial jobs, the artwork in progress was taken down and put into a corner so we could have more space, which really affected the art production. Two years ago I was awarded a free studio space for a year at Smack Mellon, a fantastic art space here in Brooklyn. With an outside studio I was able to kick the artwork back into high gear. So after the residency ended, I knew I needed to have more space, so now I have a studio in the Brownsville section of Brooklyn. We still do the majority of building the sets here in the apartment, then install and photograph them in the Brownsville studio.

JTD: Perhaps more than any other photographer I know, you work on one photograph for a very long time. And, in addition to that, your projects are long-term, spanning many years, and even decades. How do you sustain your work (and yourself) when working on such long-term endeavors?

LN: I really do not know of any other way of working. I want to tell stories and I take as much time as I need to tell them. There’s nothing worse for me than to rush through a scene to make a deadline. There are a few of my images I would love to go back to remake because I think they could have been better.

I keep a list of potential ideas on my phone and carry them with me for years. If the idea sticks with me, then it is meant to be and it will eventually happen. Because there are so many steps involved in creating each image- designing the scene and the various elements within, the physical construction, painting and detailing, photographing the diorama- we set smaller goals along the way. This is also another case where being a duo is helpful. If one of us is feeling stuck or overwhelmed, the other can take over for a bit and often interjects some new life into the scene.

Now, all that being said, there are times when it is just plain boring. It is usually when there is a great deal of mundane work to be done, like making a large number of plants to fill a space. You just have to put on some good music or a podcast and slog through. Knowing that the work to be done is finite does help… a little.

Shoe Store

JTD: If you had unlimited space, time, and money, what would your dream diorama be? Is there something you would love to make but can’t?

LN: It’s more of a “can’t” at this moment. I want to venture into outer space and create planetary colonies, asteroid haulers, space ships, etc. The problem is that I’m not a very free form type of artist. I get flustered if I’m presented with too many possibilities. I feel more comfortable looking at something that already exists and reimagining it. I’m envious of the artists who can easily draw or build a spaceship purely out of imagination. I’ve been watching interviews with a legendary prop builder, Colin Cantwell. He worked on 2001: A Space Odyssey and also Star Wars. He’s phenomenal! But listening to his process, which was very instinctual, was inspiring. Maybe I just haven’t worked those creative muscles yet, or allowed myself the time and space to just play with more mechanical elements. But yeah… space.

Space Center

JTD: I know you have solo exhibitions coming up at ClampArt in New York, NY (December) and at the Catherine Edelman Gallery in Chicago, IL. What else is on the horizon for you? What are you currently working on?

I’m currently working on the final image for the ClampArt show, which opens November 30. I promised to have a new image for the Catherine Edelman Show, so I’ll be starting this image in the coming weeks. I actually have two images in mind for Catherine Edelman, but not sure there will be enough time for two new images. Kathleen and I have been asked to create a diorama for an upcoming exhibition at the Palo Alto Art Center in California. The show opens late January. And since the model will be the artwork on view, there’s a lot of planning for this.

After all this, the next show on the horizon is for the gallery in Munich, Germany. We have three interior scenes we would like to create. We have enough work to keep us busy until next summer.

JTD: Thanks so much, Lori- it has been great talking with you and I’m looking forward to seeing the new work!