Q&A: Mahtab Hussain

By Hamidah Glasgow | July 14, 2016

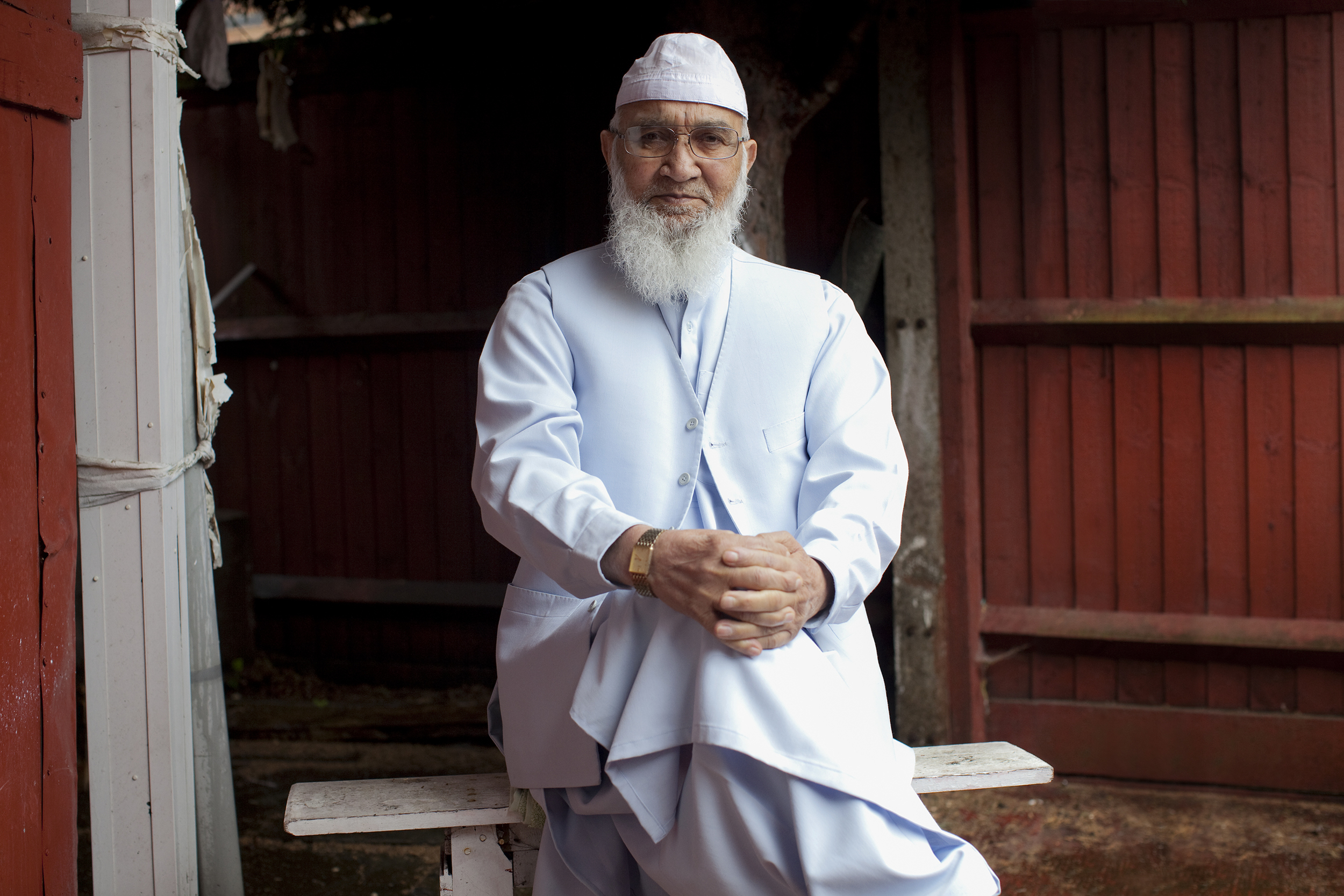

British social commentary artist, Mahtab Hussain (b. 1981), uses photography to explore the important relationship between identity, heritage, and displacement. His themes have developed through long-term photographic research and been articulated into a visual language that challenges the prevailing concepts of multiculturalism.

While seeing his practice as an exchange between the artist and sitter, Hussain believes in placing considerable emphasis on the empowerment of the sitter, and in doing so, creates portraits that force a vital interaction between sitter and viewer.

Hussain has been the recipient of numerous awards and commissions including, Arts Council England; British Council, Arts Humanities Research Council (AHRC), Multistory; he was the winner of the Curators Choice Award, Culture Cloud at New Art Exchange, Nottingham and of Format 13 Portfolio Review Award for most significant review.

HG: As I look over your work as a whole, I wonder what brought you down the path of making work representing Brits of Pakistani heritage.

MH: The idea of becoming an artist came as an undergraduate at Goldsmith College London studying BA (Hons) in History of Art during my second year. I had chosen to study Post-colonialism, a module that introduced me to black artists, artists who analyzed and responded to the cultural legacies of colonialism, racism, class, gender. Artists such as Yinka Shonibare, Chris Ofili, Carrie Mae Weems, Sonia Boyce, Lorna Simpson, and cultural theorists like Stuart Hall, Edward Said, and Frantz Fanon, turned my world on its head, forcing me to question the absence of British Asian/brown artists, a voice was missing in art history."

That module, in particular, ignited a deep routed passion in the sense that I felt connected not only to the work which these extraordinary artists were making, but also to the historical narrative they were exploring and dissecting; I experienced the transformative possibilities in art. I started to think about my experiences as a child and what identity really meant to me, and how complex this concept was for many British Asians. I wanted to create a visual history about my identity and community, a community which had seemingly been forgotten by the art establishment - that was in 2002. It took me five years, however, before I ventured into photography, and inevitably my first series would directly address identity politics, race, class and gender, a series that became known as, “You Get Me?” Since then I studied a Master in Photography, graduating with a Distinction and am currently completing a practice-based Ph.D. in Photography as well.

I initially made work focusing specifically on British Pakistani heritage; I felt this was the only community I could comment on given my background. However, I was challenged by individuals I met, they often asked why I was only focusing on British Pakistanis. Many said that they weren't just Pakistanis, but Muslims. This then opened up my scope and decided to focus on British Muslim communities. In doing so I was able to connect with individuals from all walks of life, Iraq, Afghanistan, Bangladesh, Somalia, Uganda, Saudi Arabia, Yemen to name a few.

HG: Since you began this project in 2007 the political climate has changed drastically. That combined with many tragic events in the world that have predominantly affected Muslims (Syria, Daesh, the current state of Iraq, etc.), how has your artwork and the people you photograph changed? I know that this is a complicated question but important in my mind as in the US the information we get doesn’t focus on the suffering of Muslims, who have been the majority of the victims of these events.

MH: The artwork that I’m making is gently evolving, unpacking moments that have and are defining Muslim identity globally. Events like the formation of Daesh/ISIS have become a focal point in western psyche, and as an artist, I acknowledge such events, however I’m very conscious that I do not let immediate global moments define my practice. If I react quickly to such a moment, there is a risk that the work becomes documentary and for me documentary is too top down, a specific voice, an agenda with no possibility to allow the nuances of life to enter in. There is a specific project that I am developing, reflecting on ISIS, however articulating something so charged will take a considerable amount of time in understanding the research and reflecting on what it is that I want to say.

The major change during this period for me has been a reflective journey through my work. The systematic campaigning against Muslims, thereby thrusting them into a negative light, has created a great sense of bias, i.e. Muslims, generally assumed to be the instigators of violence, should be feared. Muslims are hardly ever the victim, and if they are, they have somehow deserved it. It is shocking to experience how a society is slowly being dehumanized through the power of western cultural assumptions, and it is that which I have reflected upon at great length in my work. This power has been two-fold, on the one hand, it has de-humanized a community, whilst also germinating and encouraging a fear of itself. Such is the power of these assumptions. It’s hard to admit, but I have had to go on my own journey as an artist, reflecting and recognizing the bias that I carried from my own community. Since the Salman Rushdie affair, this potent propaganda of ‘us v. Muslims’ has allowed the bias against Muslims to be acceptable on every level in society, and for me, as it is important that we recognize this power and challenge it.

HG: Integration (or is there another word that you prefer) seems to be, in part, a matter of economics and steering (in the way that people of certain origins are pushed to live in determined places via political avenues).

MH: “Integration” is an interesting word. I often ask myself what is more important, integration or assimilation? Integration for me in this context is combining racial difference into a whole, but not necessary changing them. This was something that was encouraged in a changing society from the 60’s. Many believe this has not worked, and I too have seen the divide on both sides, “white flight” has meant that areas once occupied by “whites” are now wholly “brown/black”, and more specifically Muslim. And talking to some Muslims, the idea of moving into an area predominately white is unthinkable; there is a fear on both sides.

We now hear the word “assimilation” which means making someone, like someone else, essentially absorbing into the system and being “like one of us,” in this case, to uphold British values. I recently heard a woman on the radio talking about teaching immigrants British values and gave an example of holding doors open for others. It made me laugh a little inside as it was slightly absurd to think that is what British values are for some.

Stuart Hall once famously said, “ We are here because you were there.” The British Empire at its peak was the largest empire in history and ruled for more than a century, indeed, the phrase “the empire on which the sun never sets” described the expanse of its territories. The empire was not just about trade; it transformed the politics, language and cultural legacy of the people it governed. The breakdown of Empire was initiated by the two great wars; Britain was essentially bankrupt and the “wind of change” speech made by the British Prime Minister Harold Macmillan, affirmed that British Empire’s days were diminishing. Britain had to peacefully disengage with its territories and rebuild broken Britain. It is why I was born in the UK. My father was a young boy roughly 11 years old when he came to England with my grandfather, a skilled craftsman who served the British Army and invited to settle in England; this was in 1964. He not only fought for Britain, but helped rebuild Britain by making furniture for the NHS. He dedicated his entire working life to one company. It is because of colonialism that the movement of people became so easy.

HG: Currently, xenophobia is on the rise in the US and Europe, and your work is vital by providing representation to communities and individuals. How are these political and social changes affecting your work? I imagine a sense of urgency to tell these stories and challenge the xenophobic tide, is that right?

MH: There can be this sense of urgency to tell such stories, but one single story is not going to change the xenophobic tide that has been building for years. I’m taking on a beast of a subject, and it will take my lifetime, but also the collective voice of others around me to make a change. As an artist, I feel the strength in my work is the truthfulness in my story telling. When I talk about my practice to someone new, the response I often hear is how ‘current’ my work is. I don’t feel it is. That word, ‘current’, feels like it was a deliberate choice to choose this subject matter, but it was never a choice for me. I had to make this work and follow this path, and be honest about the British Muslim experience. I believe if we are honest as artists, then the work will always be current and meaningful. So for me, there is never this sense of urgency, and my career so far, with the ups and downs, has shown me that the work will be seen when it is right and ready.

HG: Brilliant answer. Thank you, Focusing on the long haul instead of the short term is wise and a more sophisticated approach. I look forward to following your journey as an artist.

From "You Get Me" to "Honest with You" and "Muslim Ghettos" the thread of marginalization is clear. In "The Quiet Town of Tipton" what I see is the opposite. That these families have integrated (again not sure of that word) and were still the target of hatred for their religion and heritage. Do you have insights into the seemingly universal xenophobia as a result of making your work?

MH: You are right in the sense that this particular series has the opposite narrative from “Honest With You” and “You Get Me?” In this series, it’s quite clear that the elders feel British. It made complete sense to me that they would; many of these young men and women who migrated from Pakistan and Bangladesh during the 1950’s and 60’s came from humble beginnings. When I interviewed the elders, they recalled their first memories of life and work in Britain and how, over the years, they were joined by loved ones, established their homes, families and mosques. They experienced first hand the wealth of opportunity Britain gave to them, and they are very proud of what they have achieved.

The key difference here, is that the elders still have a direct physical connection to their homeland, and this inherent ‘pull’ to their homeland, this knowledge that they could always go back, allows them to feel relaxed into accepting British identity too – the connection with their homeland acts as a sort of safety net. The difficulty lies with their children who were born in the UK, who, while feeling ostracized and segregated from mainstream British society, also have no inherent ‘pull’ to a homeland, they have no ties to their parental country and essentially they become part of the “lost generations”, clearly they are not English and when they return to their “homeland” they are told that they do not belong there either. It is here that this crisis of identity occurs.

As I said earlier, there is fear on both sides. The British fear that their British identity is under attack and diaspora into the empire has created a shift in dominant culture. There are now two new voices in Britain, the voice of the others, which in turn has created the voice of hybridity. I believe xenophobia has occurred because all sides are unwilling to move forward together, and all are holding onto identities of the past, whilst referencing history to justify their resentment towards each other. The young often speak about the difficulty of their dual identities. However, they are the exact embodiment of all their identities, one that is a hybrid of global culture.

HG: Striking about the first image of The Quiet Town of Tipton is that as a viewer when confronted with the notion of a bomb with nails in it there is an instant association with"terrorism" and that the would-be-terrorist is Muslim. When in fact, the opposite is true. The man who perpetrated the crime or acts of terror was a Ukrainian student. So many things go through my mind, but mostly I am struck by the multitude of acts of violence against Muslims that go un or under-reported due to the discrimination again Muslims. That there has developed a "knowing" about Muslims and the Muslim faith that is ill-informed. Can you speak to this and how your work is an avenue for understanding?

MH: My art practice's current core aim is to try and create a better understanding of Muslims globally. It is in the realm of art that we can truly reflect on the nuances of life. The use of a nail as the front cover of the book addresses how the media has indoctrinated our way of thinking when it comes to terror attacks. Terror attacks only seem to come from one direction at the moment: Muslims. In America, it might be specifically Middle Eastern Muslims, but specific Muslim groups are not articulated like this in the UK. I don’t want to sound preachy, but the problem with the way the media has handled terrorism globally has ostracized an entire religion for the act of a small percentage. Since 9/11 Muslims have had to endure a plethora of attacks from the media and government. I was lucky to be born at a time when negative Muslim news did not fill our new channels. I often think about how the youth in particular cope with such media and political pressures. It must be so difficult to be born into a world that actively tells you that you do not belong.

The attack in Tipton was from a self-identified racist, who was affiliated with a white supremacist group from Ukraine. He also placed two further bombs, one in Walsall and the other in Wolverhampton. His purpose was to commit “acts of terror,” his very words. I felt it was important to create a series about this particular event because it was one of the first times a nail bomb was used to attack Muslims in Britain. Through my research I have heard fearful statements from the youth; that one day Muslims will be kicked out of the UK. Some of the youth talk about a global war against Muslims- this fear is very real for them. When this event happened, I felt I needed to see how this community coped. I never thought “The Quiet Town of Tipton” would connect me to the generation of my grandfather and articulate a story about hard work, pride, and Britain.

HG: Yes, I imagine that growing up Muslim now is very difficult with the harsh rhetoric and negative stereotypes. As you put it, “it must be difficult to be born in a world that actively tells you that you do not belong.” A grave concern of mine is the further alienation of young Muslims. How will the next generation understand themselves in the larger society and more importantly how will society understand them?

MH: On a more positive note, I do feel the next generation has one of the strongest voices the community has ever had. Social media has created a stronger collective voice globally while also pushing positive role models in those spaces. Through my research, I have connected with so many wonderful thinkers and pioneers helping to challenge the negative stereotypes and labels. I also believe that the younger strands of society are tired of hearing such negative rhetoric, and they are now willing to take a stance. For example, London has just elected its first Muslim mayor, and that is a statement of change in itself.

HG: Your work is vital, and there is so much to talk about in regards to British Muslim communities. What are the most pressing questions/issues for you right now?

MH: I don’t have a pressing issue. I think if I thought about all the questions and issues I wanted to tackle I would probably be overwhelmed and not make any work. I tend to let the ideas develop over time making sure there is a specific theme and thread running through my practice overall. That is the best I can do, with the hope it will connect with others.

HG: What’s next for you?

MH: I’ve just opened my touring show, The Commonality of Strangers, at Farm Cultural Park, Favara, in southern Sicily; the commission was instigated by New Art Exchange in Nottingham, and it is a series that honestly articulates the migrant story. I spent four fantastic days in Favara with extraordinary people, and I am traveling back at the end of the summer to make new work there. Right now, I’m about to start a summer commission with Ikon Gallery, Birmingham - they have given me their narrow boat, and I’m making work which tells the story of mass displacement from the building of the Manga Dam located on the Jhelum River in the Mirpur District of Azad Kashmir, Pakistan. Construction began in 1961 and was opened in 1967, it displaced well over 110,000 people and submerged over 100 towns and villages and is one of the main reasons why there is such a large Pakistani Kashmiri community in the UK. I’m making a series of tin-type portraits of the residents who were displaced by the dam. Indeed, my family was part of this displacement too. I will also be working with clay for the first time, building a traditional ‘clay house’ in the gallery, a home that my mother would have grown up in.

In Spring 2017, MACK is publishing a monograph of my series, You Get Me?, which focuses on the changing identity of young, working-class Asian men in contemporary Britain. At the same time, Rivington Place at Autograph is featuring a touring exhibition of my work. All this while working on my Ph.D., which is three further projects on the British Muslim experience, so there’s a lot going on!

HG: Thank you for sharing your work and thoughts with us. I'll be following your journey and am thrilled that your work is getting the attention it deserves. These new projects sound wonderful, keep us posted. Perhaps we can do another interview in the years to come.

To purchase Mahtab Hussain's book, The Quiet Town of Tipton, click here.