Q&A: Mary Ann Peters

By Rafael Soldi

Mary Ann Peters is an artist whose combined studio work, installations, public art projects and arts activism have made noted contributions to the Northwest and nationally for over 30 years. Most recently her work has focused on the overlap of contemporary events with splintered histories in the Middle East. Her awards include the 2015 Stranger Genius Award in Visual Art, a 2013 Art Matters Foundation research grant, the MacDowell Colony Pollock Krasner Fellowship (2011), the Civita Institute Fellowship (2004) and the Behnke Foundation Neddy Award in Painting (2000). She is a founder of COCA (Center on Contemporary Art), a recipient of the Artist Trust Leadership and Arts Award, and former board member and board president of NCFE (National Campaign for Freedom of Expression), the seminal group who defended artist rights and the First Amendment during the Helms era. She lives and works in Seattle, Washington.

Rafael Soldi: Your family migrated from Lebanon to the United States, how has this relationship to your heritage changed over time and manifested in your work?

Mary Ann Peters: I wouldn’t say that my relationship to my heritage has changed but more that it has become a fuller presence in my thinking…beyond nostalgia and my singular family history. As my experiences from traveling in the region intersected with concerted research on my part around 20th migration histories, I began to see the threads of my personal narratives overlapping on the bigger issues of forced migrations in general. That there has been a major upheaval in the current Middle East predicated by the Syrian civil war and the collapse of the Arab Spring allowed me to take more seriously my ability to use these circumstances as pivot points in my work. Always…..ALWAYS….is the backdrop of whether I can be additive and ethical with this subject matter. My misgivings had been that as a second generation Arab American, assessing events from afar, my gestures would mainly be interpretive. Meeting Rabih Mroue’ assured me that i could. Much of his work is a combination of observation and threaded factual episodes he discovered. So his work became a great model and inspiration for me.

RS: Your practice roughly breaks down into painting/illustration—from works on paper to large public murals—and sculpture/installation. Your installation work in particular addresses themes of Arab descent. In the early 1990’s you created ‘find the Syrian boys’ at the Bellevue Art Museum, an in the recent years you’ve created a series of ‘impossible monuments’—what is an impossible monument? Why are these important to you?

AC: I actually don’t separate my various approaches to my work as you have broken it down. I see all of it as tendrilled to the other. Some work just translates better in one medium over the other. The “impossible monuments” are deliberately temporary installations because the concept is grounded in information that is fleeting or minimized yet also integral to understanding larger issues. So I identify an impossible monument as an incident or event that deserves reverence but by virtue of it’s ordinariness or incidental nature would never be elevated to the status of a monument. I also understand that little histories are the backbone of much larger narratives and often more accessible.

find the Syrian boys, 1992

RS: You just wrapped up a residency at Oxbow, what did you create there?

AC: At Oxbow I made 2 installations. One, titled “impossible monument (nothing but the memory)", addressed how the glut of information we try to process daily intertwines trauma and trivia and intercepts our ability to discern issues that deserve our attention. I used the incident that fleeing refugees attempting to cross the Mediterranean were sold faulty life jackets stuffed with newspapers. My piece was a massive bulging wall of crumpled newspapers where at discreet intervals broken and torn life jackets or packs were buried. The second installation was called “impossible monument (ghosting)” and referred to aerial views of destroyed cities in Syria, how they are at once beautiful and haunting. I had also been reading accounts by survivors who spoke of their neighborhoods as if they were in tact, holding the form of the architecture in their descriptions. I used the floor of the gallery to guide me in an ink drawing that looked topographical and hovering over the drawing was a canopy of sheer burned architectural forms, the ghost of the city.

impossible monument (nothing but the memory) and impossible monument (ghosting) at Oxbow

RS: One of your pieces at Oxbow turns a crack on the floor into a river, which transported me to a haunting painting you’ve done titled ‘painting the river red’, would you elaborate on this painting?

AC: "Painting the river red” was my interpretation of an event that happened in Hama, Syria in 1982. The city is a on a river with a large viaduct system tied to the river. The father of the current Assad bombed the city after protests against his government by the Muslim Brotherhood. His assault on the city was squelched, communication systems were closed, and the incident was buried. Estimates recorded close to 20,000 civilians were killed with some records even higher.

To commemorate the event people to this day go to one of the waterwheels on the river and pour red dye into the river, I believe to mourn the loss but also to give life back to the river. So that’s a very abbreviated story.

painting the river red, 2012

RS: We chatted at length about ethical questions. How do you manage honoring where you come from and addressing what could potentially have been your fate from your position of Western privilege?

Any artist that chooses to use their work as a vehicle to address social or political concerns also has to grapple with the cultural ramifications of their actions, including that their actions are informed by where they live and their maturation as a thinker and maker. There are always ethical questions to be posed especially if the topic of interest is distanced. My privilege is happenstance like many of us. Nevertheless my privilege was also fought for by my family years ago. (My father’s family was run out of Paris, Texas by the Klan in the early 1900’s. another story) This being said simply because an artist wants to comment on volatile narratives is not enough. They have to consider whether their input is proactive and not self aggrandizing. The point is to generate consideration and reflection beyond the thing we make. We have to be ready for the afterlife of work as well as in the immediacy of presentation. Being conversant and receptive is part of the work. It’s the ethics beyond aesthetics. It’s understanding that the those on the receiving end of your efforts are key to its success.

down deep, 2012

RS: In this charged political climate many artists are itching to address conflict—what are some questions artists can ask themselves in their process to avoid taking advantage of somebody else’s demise?

I would never discourage anyone from wanting to alleviate the suffering of others which is usually the common ground of socio-political work. I don’t believe in proprietary status where activism is concerned. What we are experiencing today is not new though it may feel that way. Still the questions an artist needs to ask is how much of the lineage of the conflicts they are dismayed by do they understand? How much history are they willing to look for? How much of that history is stagnant and deserving of dismantling, including what appears to have been useful? It’s the questions that clarify a vast sweep of concern and give precedence to details that one can actually act upon. If you’re thoughtful taking advantage of someone else’s demise can be a moot point. But whenever your work interfaces with the public, in that seam between private and shared, a degree of control vanishes. Every artist needs to be ready for the potential repercussions.

RS: Let’s talk about beauty. Opposite your conceptual interests lies a visceral attraction to beauty. I think many artists struggle with this, we can’t help but make beautiful things. All of your work, regardless of medium, is rich in detail, color and texture—every formal choice is considered. Your two-dimensional work often features targets, explosions, blood, cities in ruin and other nods to war-torn humanity; yet they’re never void of whimsy and aesthetic gravitas.

I mentioned to you that I read most of your paintings as landscapes, and there is such a long tradition in history of landscapes as these monumental, sublime manifestations of mother nature’s never-ending beauty. But right alongside it you have an equally rich history of images of battle and war; I feel your work sits at the intersection of these two: conflict and sublime beauty. What is your relationship to beauty and how have you negotiated your own acceptance of it? When we make work that holds such heavy conceptual weight, how do we measure its aesthetic value?

I am well aware of the power of beauty in setting the stage for any number of responses to my work, sublime to contentious. Half of my effort is to seduce the viewer into sitting with me while I pose a broader sense of my conceptual reasoning for making a work. Beauty is a tool to do that and has always been the nature of my hand and my vision. We need to remember that whatever we are commenting on is only a piece of the experience. The most impoverished situations have a measure of joy and hope in the mix. Accepting that is respectful and necessary.

My use of landscape aligned images is an unconscious discussion of place. I am in a constant internal conversation about attachment, heritage, nostalgia, outrage, confusion, and memory, to name a few. I am well aware that one core concern in my work is revitalizing lost histories and understanding how those histories are reconstituted beyond their origins. Landscape is a universal signal for place. It’s the common denominator.

breath and cinder, 2012

find the Syrian boys (detail), 1992

impossible monument (on my eyes and my head), 2015

impossible monument (on my eyes and my head), 2015

messy heaven, 2016

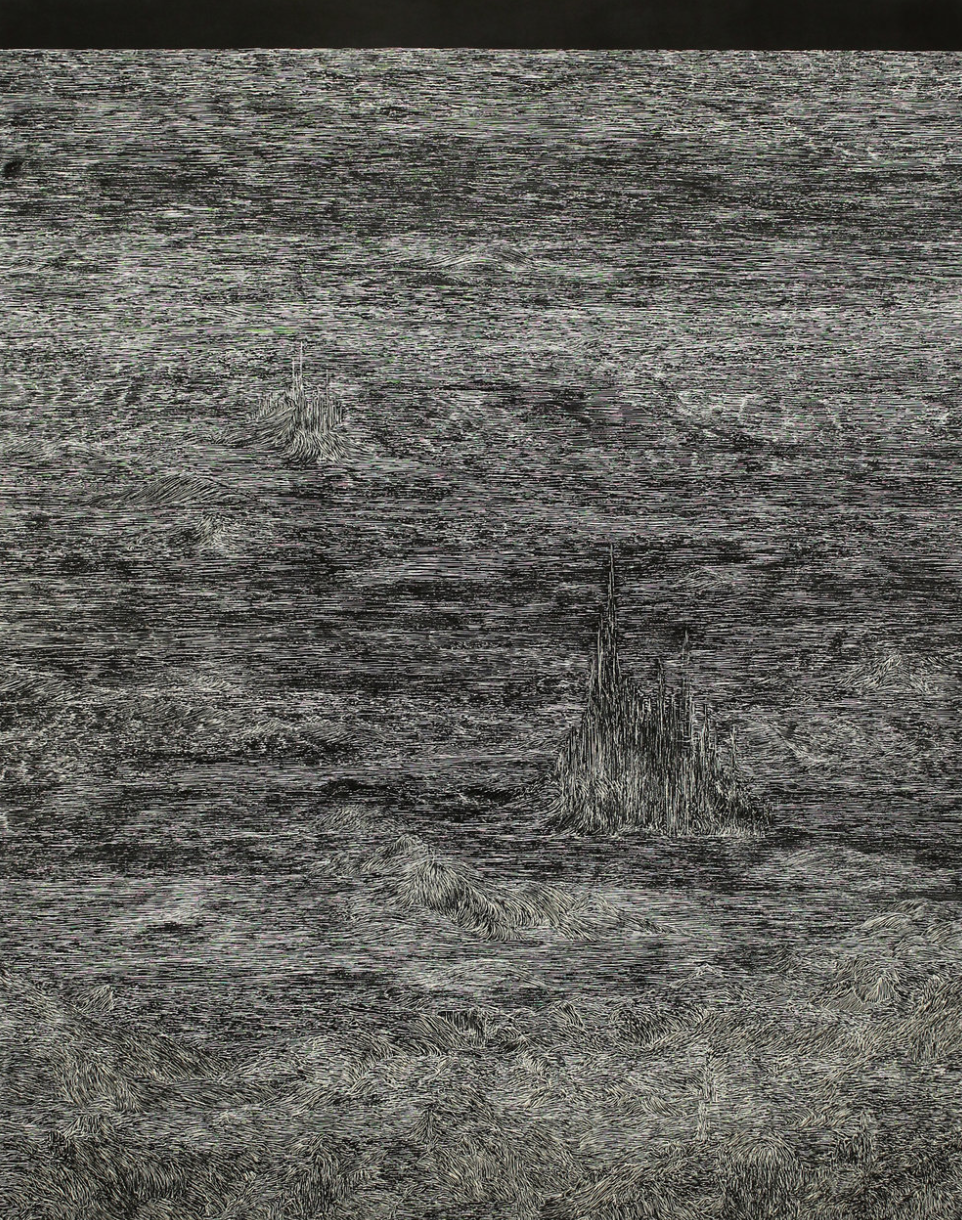

this trembling turf, 2016

this trembling turf (echo), 2016

impossible monument (flotsam), 2015

story board 2, 2015

what stays the same is never so, 2014

then and now, 2012

every miss a hit, 2012

shift (from a history of ruin), 2011

All images © Mary Ann Peters