Q&A: melissa kreider

By Zora J Murff | Published November 25th, 2016

Melissa Kreider is a photographer who grew up in Akron, OH. She uses photography to raise awareness about the realities many survivors of domestic and sexual assault face. She received her Bachelor of Fine Arts at the University of Akron in Akron, Ohio. She's now pursuing her Master of Fine Arts in Photography at The University of Iowa in Iowa City, Iowa. Melissa also curates the project Don't Smile, "a space devoted to showcasing photography by women artists".

Melissa and I discuss her project Remnants, a visual exploration of sexual violence perpetrated on women and the processes they endure after the fact. We also discuss her curatorial project Don't Smile. Melissa is currently funding the first publication of Remnants through Kickstarter, and her campaign was chosen by the site as a "Project We Love."

Zora J Murff: How did you get into photography?

Melissa Kreider: I have parents who were interested in photography. They had a few 35mm cameras, so it seemed like natural progression when I picked one up around the age of 10. Someone in my family noticed my interest and gave me Polaroid camera (it was pink and I covered it in stickers) shortly after.

Make no mistake, I didn’t develop any sort of artistic voice or conceptual interests until college, but I made a lot of pictures before that. I’ve always found something incredibly satisfying about using the camera to record experiences. My relationship with photography grew as I grew.

ZJM: Tell me about Remnants (this can be a loose explanation or a more formal artist statement).

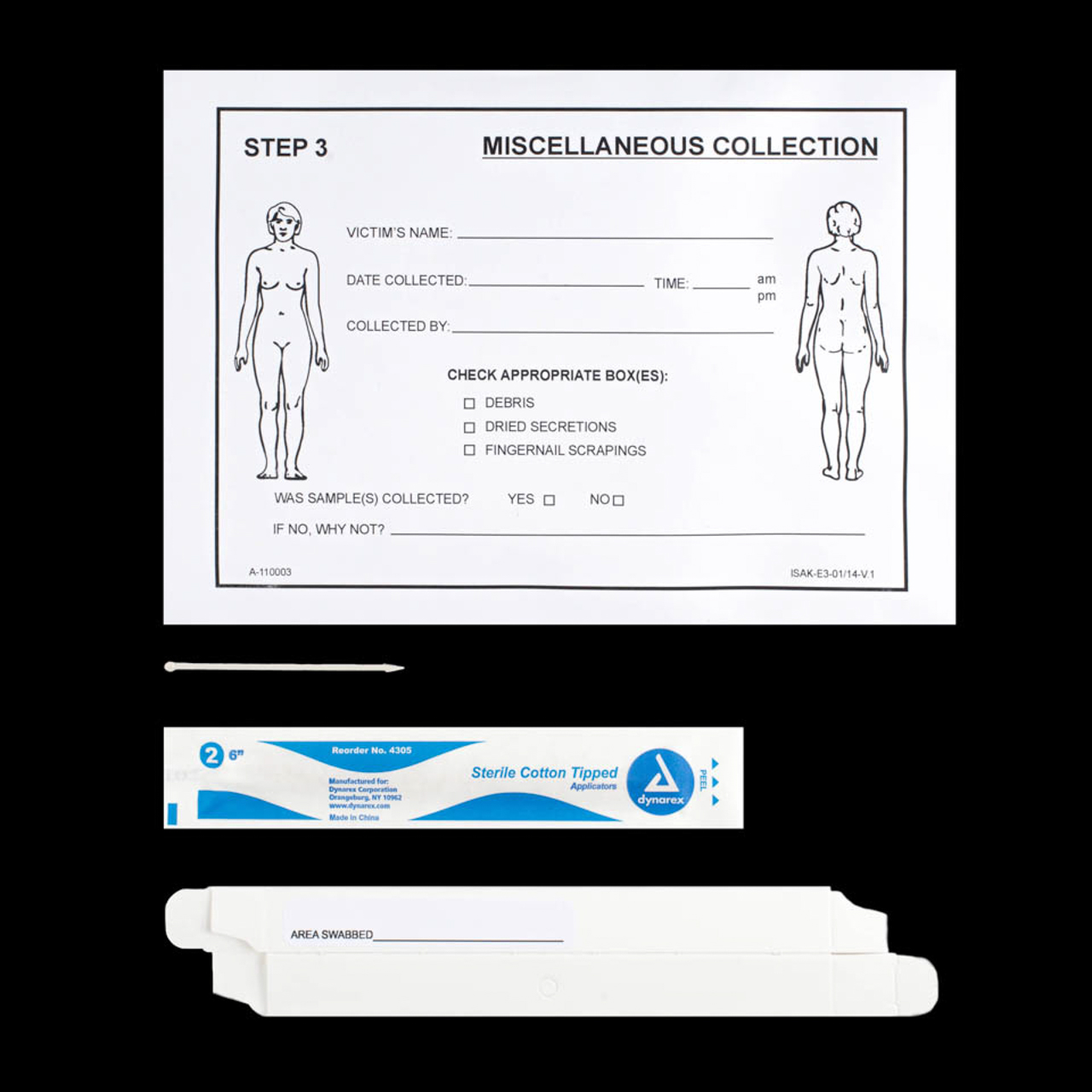

MK: Remnants describes the successes or failures of the reactionary structures that are responsible for engaging victims of sexual and domestic abuse. It is an exploration of each site, object, or situation that a survivor of intimate partner violence might experience. I am also working directly with survivors from all walks of life to hear their stories and empower them through the use of photography.

The photography I am creating ranges from sites of sexual and domestic assault, to the shelters survivors find themselves, to the sexual assault evidence collections kits survivors have to endure, to the backlog of rape kits in police evidence rooms, to the survivors themselves. All of these aspects create a complicated and intimidating maze of steps a survivor may maneuver if they choose to rely on the justice system for assistance or justice. This work does not serve to trigger or create a negative response, but exists as photographic evidence of the reality many face when assaulted.

ZJM: Why did you decide to focus on sexual assault?

MK: I’ve experienced sexual assault and harassment in the past when I was in my later teen years. These incidents always took place around those I knew and trusted, in spaces that I deemed as safe. I indirectly made a body of work about this as my undergraduate senior show titled, “You Can’t Go Home Again.” It’s named after the Thomas Wolfe novel of the same name in which the character has moved away and returns for a funeral to find that he relates to his hometown completely differently as a changed person. I think everyone can relate to this feeling if they’ve left-but for me it was coming to terms that what was once a safe town had now transformed into something strange and unfamiliar.

ZJM: The series unfolds in what seem like chapters. Why did you feel it was important to approach your subject matter in this manner?

MK: I want the viewer to be able to follow some sort of linear narrative through what a survivor might experience. I began at the landscapes where domestic and sexual assault happen by mining police logs, traveling to those spaces, and photographing them. I chose the landscape first not only because it is the most accessible, but because these are the initial spaces that bear witness to these crimes.

Many survivors don’t make it past these sites. A majority don’t get a rape kit exam because it is re-traumatizing, and even if they do, it is incredibly difficult to prosecute. Kits end up sitting on shelves collecting dust. If a kit does get sent to a crime lab, it is still up to the police or the survivor to press charges when the test results come back. Many police departments aren’t equipped to handle victim notification and, subsequently, their reentry into the system, and most survivors are unwilling to relive their experience over and over again in court to seek justice. It is a complex web whose blame doesn’t fall on one, but many organizations. Including that who stigmatizes survivors of sexual assault.

I find it important to assemble this work into a linear narrative so viewers can easily understand. The sites, each step of a rape kit, the crime labs, and the backlog. I end with the images of survivors to humanize the issue after many images of objects and sterile spaces—to drive home the point that all of these spaces lead back to a person. Sexual and domestic assault survivors turn into a site themselves when they consent to an invasive and re-traumatizing exam.

After all, it is indigestible for those that are experiencing it by force. What about those that are viewing the work voluntarily?

ZJM: This is a brave undertaking. You currently have a Kickstarter to fund the a publication of Remnants. Can you tell me more about this?

MK: The first book for Remnants is made with those that have limited visual literacy in mind. I feel incredibly ability for public servants and their role in resolving this issue, so the book is designed to educate members of Congress about the urgent need for funding allocated toward Rape Kit DNA Testing.

It is my hope that Remnants will inform and incite an emotional response in those with the positions of power to enact change and promote education. Using a linear narrative opening with real, transcribed 911 calls, the book chronicles the landscapes and often personal objects left behind in the wake of sexual or domestic assault.

I’m asking for Kickstarter contributions to print and ship the book to every member of Congress.

ZJM: I recently sent you a link to Jörg Colberg's opinion post "Now What?" and this quote resonated with you:

"This is not necessarily to say that per se there’s something wrong with these kinds of books. But I believe there is a lot wrong with our insularity, our inability (if not unwillingness) to cross a divide, while, and this is where this gets really ironic, a lot of the work in our books might even be made about the very people who will just shake their heads since they can’t understand them."

Can you elaborate on that a bit?

MK: This resistance to work that might speak to a larger audience or even those that might be in our work that Colberg is alluding to here is something that I have yet to understand and that I think about a lot within my own practice. The quote stood out to me because the format of the book I’ve made for Congress isn’t by any means a traditional monograph or even an artist’s book, but it is made for the purpose of educating a specific group of people and I’ve caught a little bit of flak for that. I pair my photographs with information I’ve gathered from the Bureau of Justice Statistics and other government sources. I’m making work to incite an emotional response and hopefully begin to foster some sort of empathy. I don’t think that I’m devaluing my work by making it accessible to those that need convincing. The whole article felt sort of validating. If I was making a book for myself or other artists, it would look different, but that isn’t the case this time around.

ZJM: Along with your own research, you also curate the online publication Don’t Smile. When did you start the project? What do you want to accomplish with it?

MK: I started Don’t Smile in April 2016 to promote and celebrate exceptional photography made by women. I wanted to carve out a space of the internet for women photographers, and while it is a huge undertaking, I am thrilled that it has been working out and people have been responding to it. I absolutely love doing it. It is a great break from my own work, which is often emotionally taxing, when I can do something productive for others.

I am creating an exceptional mix of established and emerging artists on the internet that is accessible for all. I’m inviting other women to be guest jurors for Don’t Smile’s quarterly exhibitions and gearing up to have weekly features rather than bi-weekly.

In the future I want to bring Don’t Smile into gallery spaces, zines, and maybe publications-but those are tentative plans! Right now I’m focused on creating a reliable online presence.

ZJM: Thank you, Melissa for the work that you're doing. It's brave, and timely, and we definitely need more like it in these times.

MK: Thank you, Zora.

To donate to Melissa's Kickstarter campaign or to submit to Don't Smile, please follow the links below.

www.kickstarter.com

www.dont-smile.com

All images © Melissa Kreider