Q&A: Michèle Pearson Clarke

By Jess T. Dugan | May 18, 2021

Michèle Pearson Clarke is a Trinidad-born artist, writer and educator. Working primarily in photography and video, her work situates grief as a site of possibility for social engagement and political connection. She has exhibited at Le Musée des beaux-arts de Montréal; the Art Gallery of Nova Scotia; the Royal Ontario Museum; LagosPhoto Festival; Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago; Maryland Institute College of Art; ltd los angeles; and Ryerson Image Centre and Gallery 44 Centre for Contemporary Art, Toronto. Based in Toronto, Clarke holds an MSW from the University of Toronto, and in 2015, she received her MFA in Documentary Media Studies from Ryerson University. Most recently, Clarke has been awarded the Toronto Friends of the Visual Arts 2019 Finalist Artist Prize, and in 2020, her work was added to the collection of the National Gallery of Canada. She is currently the inaugural 2020-2021 artist-in-residence at the University of Toronto’s Bonham Centre for Sexual Diversity Studies, and the Photo Laureate for the City of Toronto (2019-2022).

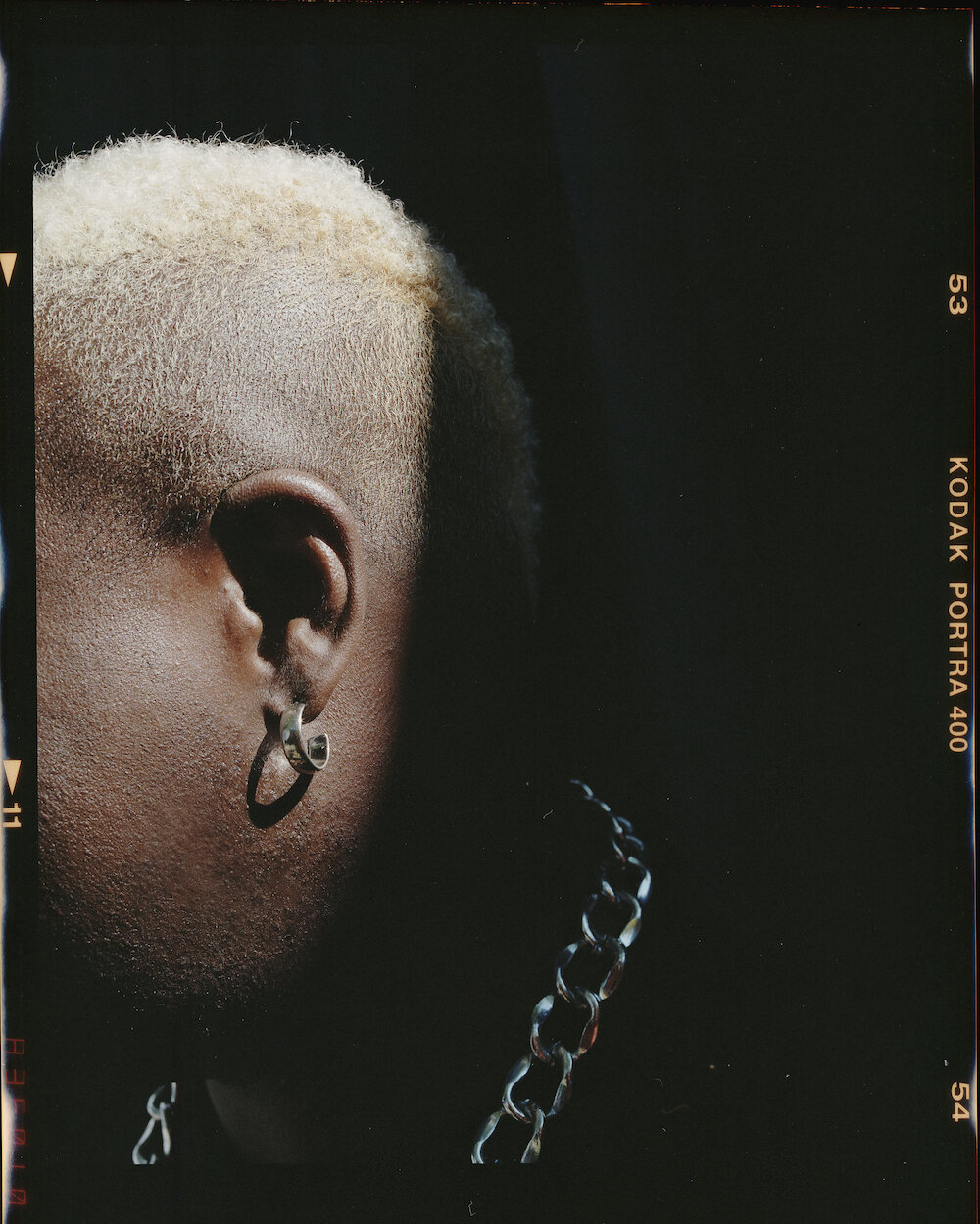

Michèle Pearson Clarke, photo by Jessica Laforet

Jess T. Dugan: Hello Michèle! Thank you so much for taking the time to speak with me today. I’m excited to jump into your curatorial practice in a moment, but before we do that, could you tell me about yourself as an artist and what your path was to getting to where you are today?

Michèle Pearson Clarke: Thanks to you too Jess, for inviting me to talk with you! So, I work primarily in photography and video, and my projects all revolve around Black and/or queer experiences of longing and loss. My work also tends to be autoethnographic, and it was actually my own grief experience that sent me back to school at age 40 to get an MFA in Documentary Media Studies from Ryerson University.

Before that, I studied for an MSW and worked in sexual health education and LGBT health promotion. But after my mother died in 2011, pursuing a formal artistic practice somehow became a way to survive and process that trauma. I was already in love with experimental film and video, and I had made a couple of short works inspired by my time volunteering with the Inside Out LGBT Film Festival. That festival was both a type of film school as well as my introduction to a queer artistic community that was completely supportive and helped me give myself the permission I needed.

And then, since completing my MFA in 2015, I have focused on building a broad practice that includes teaching and writing and mentorship. With all of these different forms of my work, I’m very much interested in situating grief as a site of possibility for social engagement and political connection.

JTD: I love this sentence from your statement about your project 10 x 10, for which you photographed ten queer and trans people in a public pool, a place that is often difficult for queer folks to navigate: “The strength to be vulnerable is a tried and true strategy of queer resistance.” This idea resonates with me deeply, and is a core belief in my own practice, but I’m not sure I’ve ever heard it articulated so directly. Can you expand on this idea as it relates to your practice as both an artist and curator?

MPC: Vulnerability is about exposure and being seen, and I’m really struck by our paradoxical relationship with it – many of us revere it as strength in others, but as weakness in ourselves. But through the process of coming out, whether just privately or more publicly, I think queer and trans folks get to build that muscle differently. If we’re lucky, we get to access the power and agency that can come from taking that kind of emotional risk, and this often translates into other areas of our lives.

That’s certainly how it’s been for me, and I also learned a lot about how our communities engage with vulnerability in my former career. Now, as an artist and curator, I try to create opportunities for other queers to lean into the discomfort of vulnerability, as a way of claiming something for themselves and for us.

Wynne Neilly & Kyle Lasky, Our Favourite Spot, 2018

JTD: That’s beautiful, I love that. You are currently the Photo Laureate for the City of Toronto, which is a pretty unique position, yes? What kinds of things have you been doing in this role? How have you thought about ideas of advocacy, diversity, inclusion, and community engagement in this position?

MPC: Yes, absolutely. This is the only Photo Laureate position in Canada, and one of only a handful in the world that I know of. It’s also still quite new here, as I’m only the second person to serve. And all of those ideas you mentioned are literally what the role requires. You do get the freedom to make the role your own, but the main intent is that you be an advocate for photography and create engagement and dialogue on issues faced by Torontonians.

I actually make more moving image work than I do photographs, but I’m completely preoccupied with thinking about what photographs do, and so I’ve been most interested in focusing on visual literacy in my tenure. Unfortunately, several planned projects were scuttled by the pandemic, but for the past year-and-a-half, I’ve been writing a monthly column in The Toronto Star, and I use my Instagram account, @tophotolaureate, as a platform to reflect on relevant issues and to celebrate and showcase the diversity and work of Toronto photographers. I also give talks, and participate in juries and on panel discussions as much as possible.

My signature project has been postponed now, until next summer, and that will see me working with twenty different photographers for a project called Toronto Park Portraits. It’s funded through ArtworxTO, which is Toronto’s Year of Public Art, and we’ll be setting up pop-up outdoor studios and shooting free family portraits in parks across the city. I’ll also be talking to folks about what’s going on with them, sort of taking the temperature of the city, and I’ll share photos and excerpts of these conversations on the project website and Instagram account. Hopefully, this will allow for a broader sense of connection and engagement through these portraits.

JTD: For the past year, you have been an artist-in-residence at the Bonham Centre for Sexual Diversity Studies at the University of Toronto, where you have been researching queer curatorial strategies and curating an exhibition of contemporary Canadian LGBTQ+ artists, We Buy Gold, opening soon (exact date TBD due to COVID) at TPW Gallery as part of the CONTACT Photography Festival. What led to your interest in curatorial work? I’d love to hear about what you’ve been researching this past year and your thoughts on queer curatorial strategies more broadly.

MPC: Curating wasn’t really on my radar, but when I was applying for the residency a year ago, we were in the midst of that early phase of the pandemic when mutual aid and community support were at the forefront. In that spirit, curating an exhibition felt like the best use of this residency opportunity, and it also allowed me to purposefully integrate my personal practice with my Photo Laureate role.

With the residency set within an academic setting, focusing on research also seemed to make sense, and so I just read as many queer curating articles, interviews and blog posts as possible, and then I collected and shared them on my website. I also took an online course called “Queer Art and Queer Curating” through Node Center, and I hosted an online conversation on the politics and practices of queer curating in Canada in March.

Through this research and these conversations, it’s clear that queer curating means many different things to different people. I’m walking away with a great appreciation of the value and importance of bringing queer ethics, collectivity and activism to the process of curating, and the possibilities that come from imagining otherwise within exhibition-making spaces. What the museum or art gallery presents, how it presents it, what it collects, how it treats artists, staff, and audiences – queer curatorial strategies have something to offer all these structural processes.

JTD: Tell me about the exhibition, We Buy Gold. What was your organizing theme, beyond focusing on contemporary Canadian LGBTQ+ photography? How did you go about finding artists?

MPC: As an artist curating for the first time, I was really guided by my own interest in the photographic gesture, and so I had a very loose theme of work that was not only queer in content, but also queer in its gaze, or perhaps in its intent, is a better way of putting it. I had a couple of artists in mind to start, and then I just hit Google and Instagram hard, looking for emerging artists across the country. I also emailed several colleagues and photography professors in art schools, explaining the show and asking for recommendations. I was looking at selecting existing work only, which allowed me to make my decisions ahead of time, before reaching out to meet with artists. You can tell I didn’t know what I was doing, because I ended up with ten artists for my first show! But as challenging as it’s been, I’m really happy with how things turned out.

Isabel Okoro, colour and feel 1, 2020

JTD: You and I spoke recently about how, in this moment, visibility and representation, on their own, aren’t necessarily enough. Rather, you were seeking work for this exhibition that operated at a deeper level, not simply saying “look at us, we exist,” but saying something more complex through the representation of queer experiences. Could you expand on your thoughts around the importance—and limitations—of visibility, both in the past and in the current moment? How are the artists in your exhibition representing queerness in more dynamic, nuanced ways?

MPC: Visibility is really tied to power and privilege in all kinds of ways that our communities have had to grapple with for a long time. And that means both the costs and the benefits weren’t equitably distributed in the past, and they still aren’t today. But there’s no denying the important political work carried out by previous generations of queer and trans photographers in bringing visibility to our communities.

Documenting our existence was absolutely necessary, given the pervasive omissions and active erasures of our lives, often in our own personal spheres, and definitely in the public sphere. But no matter the form, visibility always obscures as much as it reveals, and these days, when our images and our experiences are so often co-opted by dominant systems, then what are we really looking at?

At the same time, it’s also these political and cultural gains that have broadened the visual landscape that we contemporary photographers get to traverse. Our forebears made more space for us, so that we could ask different photographic questions or we could explore some messiness. While they’re not entirely free of visibility’s demands, I think the artists in We Buy Gold are all doing that in their own ways.

JTD: Were there things that surprised you during the process of curating the show?

MPC: Actually, despite what I just said, it surprised me how many younger LGBTQ artists still seem primarily concerned with visibility and still feel so unseen. Portraiture was overwhelmingly dominant, and there wasn’t as much conceptual or abstract work as I was expecting. I was also pleasantly taken aback by how wonderful it feels to be able to call someone up on Zoom and offer them a show. Conversely, I wasn’t prepared to feel like as much of a gatekeeper as I did at times, and I realize that I didn’t fully think through the power that I was giving myself by choosing to curate.

JTD: In conjunction with this exhibition, you have also organized a panel discussion in collaboration with the Art Gallery of Ontario that includes yourself, Sophie Hackett, Curator of Photography at the AGO, and three queer artists, including myself, Paul Mgapi Sepuya, and Ka-Man Tse. What were your thoughts behind organizing this program, and how do you hope it contributes to the exhibition and/or helps to promote work by contemporary Canadian LGBTQ+ artists?

MPC: Conversation is one of my favourite ways of connecting and engaging and learning, and since the online environment has made it easier to reach people, this program gave me the chance to just go for it and bring together a queer dream team. Sophie is both a friend and a colleague, and with the AGO’s support on board, I was able to invite artists of your calibre and profile to join us and hopefully create an interesting event for our audiences.

Given that I have spent the past nine months looking at the work of Canadian photographers, I was also really interested in expanding the context of thinking about what I’ve been seeing. Queer collectivity and queer kinship are strong threads here for me, and I liked the idea of extending the exhibition’s community across the border, and promoting the work of these photographers to a wider audience. They’re all so talented and I would love to see more career opportunities come their way.

JTD: Is there anything else about the exhibition or related programming you’d like to add?

MPC: The rest of our programming is on hold for now as we still have very restrictive lockdown conditions in Ontario, but we’re really hoping to do a Pride event where we offer free headshots to local LGBTQ artists. We’ll see. I would also like to invite folks to visit our exhibition website, which includes specially commissioned short essays on each of the contributing artists’ work by nine writers, most of whom were selected by the artists themselves. We will have a physical exhibition at some point this year, and we’re all so desperately looking forward to it, but it’s nice to have this virtual peek for now.

JTD: Wonderful, thank you so much Michèle!