Q&A: Mohamad Abdouni

By Jess T. Dugan | September 3, 2020

Mohamad Abdouni is a photographer, filmmaker and curator based in Beirut. He is also Editor in-Chief and Creative Director of COLD CUTS magazine, the photo journal exploring Queer Culture and the Middle East. His work has been exhibited at the Brooklyn Museum in New York, the Institute of Islamic Culture in Paris, the Foam Gallery in Amsterdam and in festivals around Europe such as IQMF and the Leeds Queer Film Festival. He has worked with the likes of Vice UK, Vogue US, Vogue Italia, Burberry, Puma, Slate, Gucci, Fendi, Farfetch, King Kong, Marie-Claire and L’officiel, whereas his personal projects tend to focus on the untold stories of Beirut and the rising Queer culture of the city through several documentaries and photo stories that have been exhibited around the world and published in Queer publications from around the globe. Whether in still photography or moving images, Abdouni seamlessly shifts between raw aesthetics and overly romanticised visuals, with music always playing a primordial part in every project.

Jess T. Dugan: Hello Mohamad! Thank you so much for taking the time to speak with me today. By way of introduction, can you tell me a bit about yourself? How did you discover photography and filmmaking, and what was your path to getting to where you are today?

Mohamad Abdouni: Hey! It’s my pleasure, I’m excited about this. Well, I’m a photographer and a filmmaker, and I’m also the founding editor in-chief of Cold Cuts magazine, the queer photo journal exploring queer culture and the Middle East.

I suppose I’ve always somehow been on a path that would logically lead me to where I am today. I’ve always been fascinated with print publications since a very early age. For as far back as I can remember I’ve always been obsessed with collecting books and magazines, mostly ones that were heavy on imagery. I attended art school in Beirut, which comes as no surprise, and naturally drifted towards photography.

Moving images came later on, well into my career. I suppose it’s quite a natural evolution from photography, they sort of go hand in hand, at least for me.

JTD: Your broader artistic practice includes fine art work, commercial and fashion work, publishing, and activism. How do these elements inform one another?

MA: I do feel like there’s quite a dichotomy with my work: the commissioned work that brings home the bacon (mostly within the fashion industry), and the work I do because it drives me and I believe in it. I wouldn’t call it activism; I don’t consider myself to be an activist. The work I do is very people-driven, and most of my projects have always started with meeting someone new, hearing a story from them that stops me in my tracks. The rest becomes a personal journey of exploring that story further or getting to know that person more, simply because I find them fascinating, and believe the world should stop and listen to their story.

As simple as it might sound, the main interaction between these different facets of my work is financial. I don’t think I would be able to do the work I truly believe I need to be doing if it weren’t for my commercial gigs that put food on the table.

JTD: That’s so interesting, and it’s nice to hear you be so candid about it. So many artists and photographers shy away from talking about those realities- thank you for sharing.

Your work centers around LGBTQ people and communities in the Middle East – you are from Beirut and currently living in Istanbul – which must come with its share of challenges. Can you tell me more about the intersection of queerness and Middle Eastern culture? How does this play out for you specifically, and in what ways does it inform your work?

MA: My drive comes mostly out of frustration, to be honest – personal frustration. As much as acquiring information today feels easy, what with social media allowing every one of us to have control over our narratives and to tell our stories from our perspectives, this has not been the case before, and our queer histories in the Middle East and the Arab world have not been well documented and preserved, nor do we have access to much information about our past as queer communities. One of the biggest challenges is the lack of documentation to build from.

There are many similarities when it comes to queer identities in the Middle East and in the Arab world, yes, but there are also many differences, and this is important to always point out. For example, from a legal standpoint, homosexuality is condemned by law in every Arab country, however in a country like Turkey, it is in fact legal to be gay (albeit this not always securing the proper rights against hate, abuse and bigotry).

JTD: As you mentioned, you are the founder and director of Cold Cuts. In addition to publishing a magazine, you also produce films- can you tell me more about this project? What was your motivation for creating Cold Cuts, and what are your plans and hopes for its future?

MA: Cold Cuts is the photo journal exploring queer culture and the Middle East. It began as a passion project, a visual collaboration between friends and photographers, which then developed into a queer Arab and Middle Eastern publication out of a combination of growth and necessity. Representation of queer Middle Eastern cultures was lacking in accuracy, substance and dignity, so Cold Cuts became an organically home-grown platform for queer histories and narratives.

The first edition of Cold Cuts was released in 2017 to wide acclaim from the press, featuring the work of over thirty creatives, photographers and performers over 172 pages. It now sits in the library collections of many of the world’s top universities.

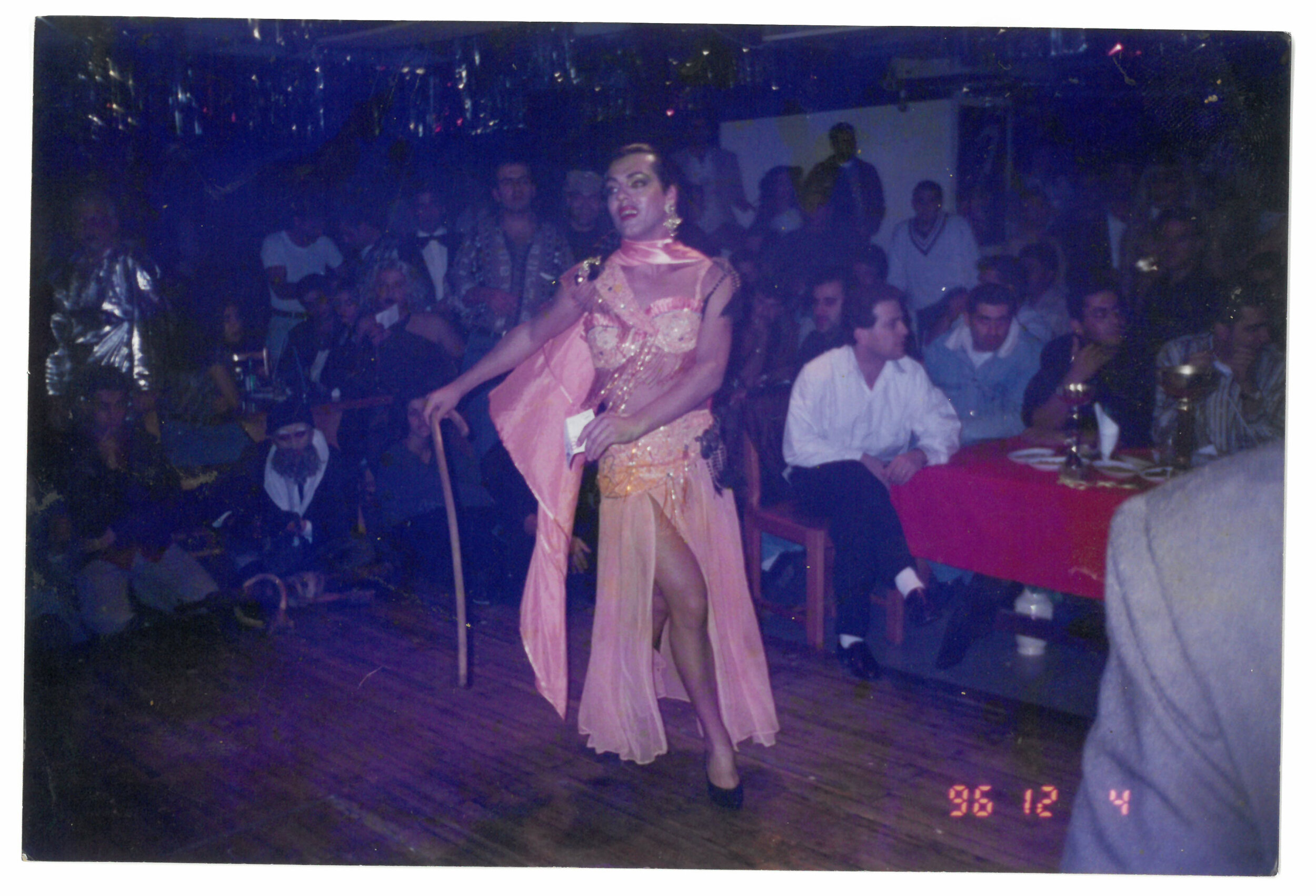

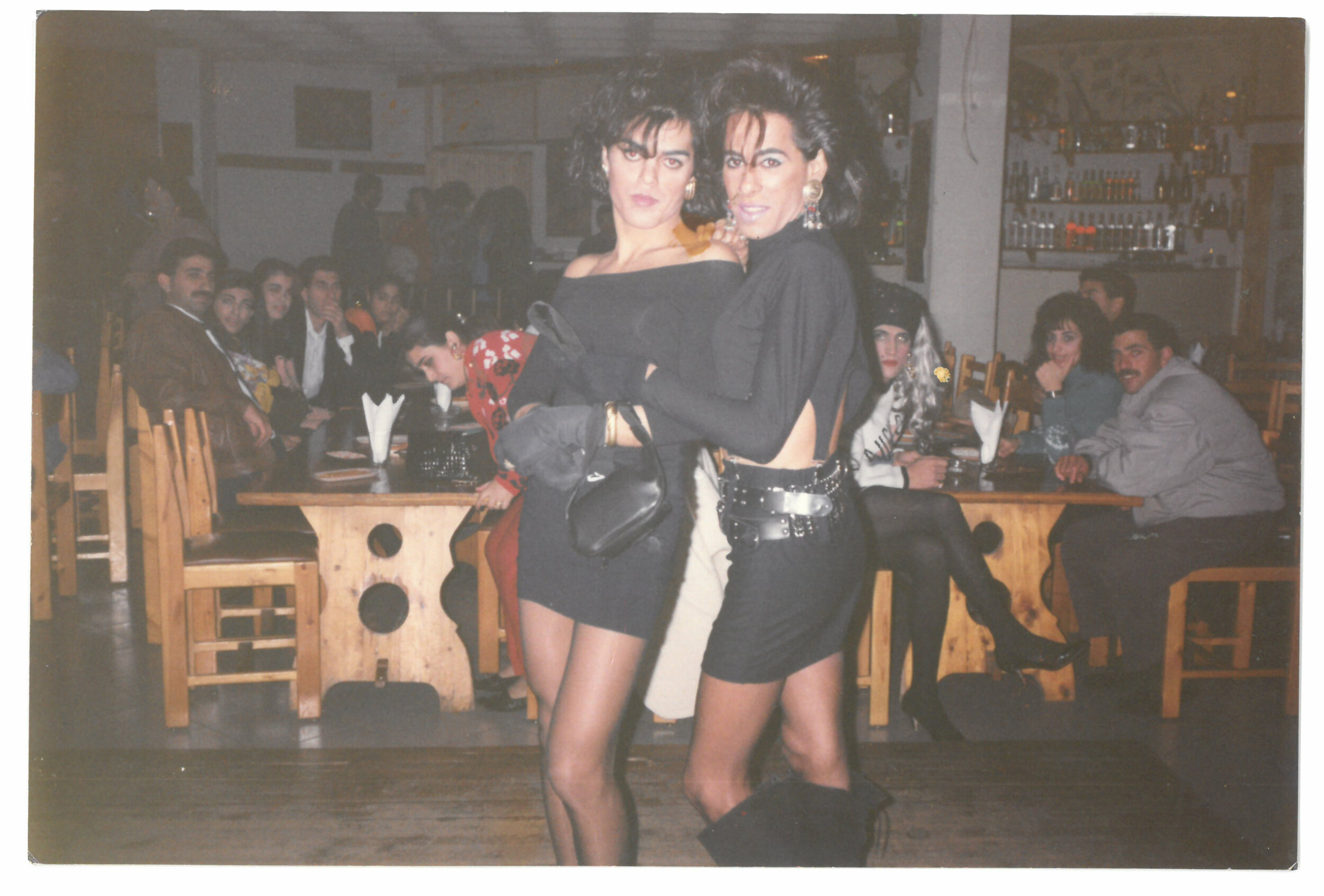

Following on from its inaugural first issue, Cold Cuts released the award-winning documentary Anya Kneez: A Queen in Beirut. The short form documentary offers a glimpse into the life of the boy who revived the Drag scene in the clubs of Beirut, and toured international film festivals around the globe.

Then in 2019, our (now sold out!) special edition, Doris & Andrea, was released to coincide with the exhibition of the same name at the Institute of Islamic Culture in Paris. The issue chronicles the lives of Doris and her genderqueer son Andrea. Together they challenge the social norms of a patriarchal society and the so-called family values of a Middle Eastern family.

In the past two years we have developed the content for two whole new editions, comprised of extraordinary photography from across the region, dozens of in-depth interviews and profiles, and histories that have taken us way beyond anything we could have ever imagined! The result will be divided in these two upcoming publications.

Still from Anya Kneez: A Queen in Beirut

JTD: Tell me more about your film, Anya Kneez: A Queen in Beirut. How did it come about? What has the reception been thus far?

MA: Ah! This short carries so much behind it. Anya Kneez happens to be my best friend; someone I’ve known and loved for almost 10 years now. This whole thing was shot with my little camera over a weekend while she was getting ready for a show in 2017, no team, no equipment, it just started out as a fun idea to get my camera and follow her around for two days.

It wasn’t until later on, a few months after that weekend, that I made a sneaky recording of a conversation we were both having together and I made her hear it the next day. What she was saying just felt so real, so universal, that we decided to couple that recording with the footage we had shot. We gathered a small and beautiful team of people to post-produce the video and next thing you know, it was no longer our baby, it was out into the world.

The reception has been great, both from within and from outside the community. Even though the short documentary was released straight to YouTube (where it still is for free viewing as intended), it still garnered attention from many queer film festivals around the globe who have asked to include it in their official selections, which is not very common practice, but it’s about time we push information to be freely accessible for everyone rather than restricting it to closed circles such as festival circuits.

JTD: For the past year, you have been working on Treat Me Like Your Mother: Trans* Histories from Beirut’s Forgotten Past, which “documents the lives of eleven trans* women living in Beirut, aged between their late thirties and late fifties, drawing visibility to an extraordinary community that has long been pushed to the shadows.” Each of your subjects sat for portraits, shared their photo archives with you, and also told you their life stories. Can you tell me more about this project? How did you come to be interested in this subject, and how did you connect with the women you featured? What was your process for working with each of them?

MA: This is such a special project. The whole thing came about after Charlie (Anya Kneez) called me in tears following an LGBTQIA+ storytelling night she had attended, where Mama Jad, a trans* woman who works with LGBTQI+ NGO Helem, had shared some of her life stories with the audience. Charlie and I talked for hours that night, he shared with me every detail he could remember and we just kept circling back to the heart-wrenching idea that we as queer people knew so little of the trans* community that had come before us, and that their stories had not been recorded in this candid manner, through their own words.

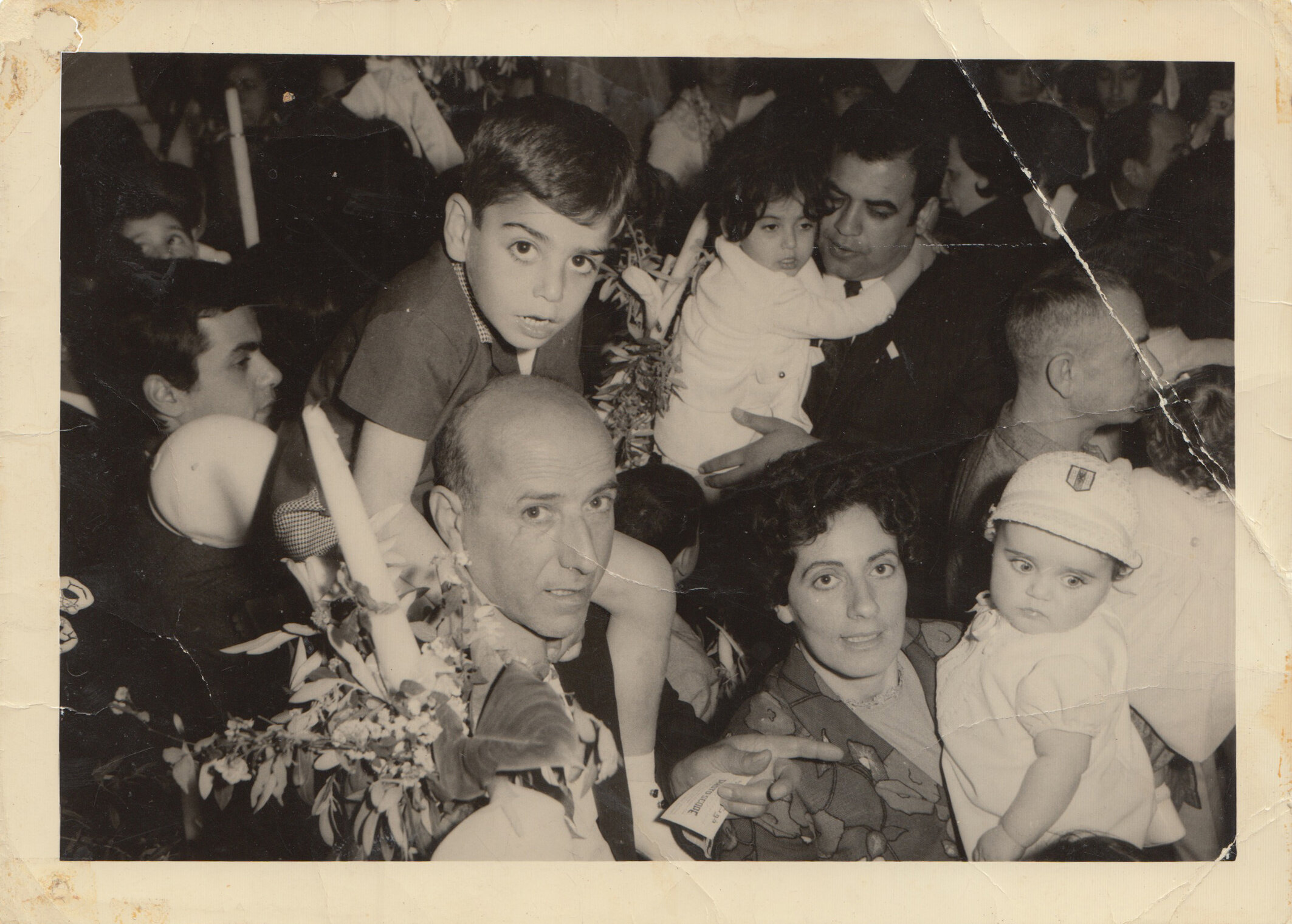

Dolly, from Treat Me Like Your Mother

We got in touch with Helem and wanted to create a special edition issue dedicated to these women that have come before us, and whose stories and lives deserve to be recorded and heard. We worked on this along with our lovely guest editor Joy Stacey and a beautiful small team of queer friends and colleagues. It was created with support from LGBTQI+ NGO Helem, the Arab Image Foundation, and culture space Station.

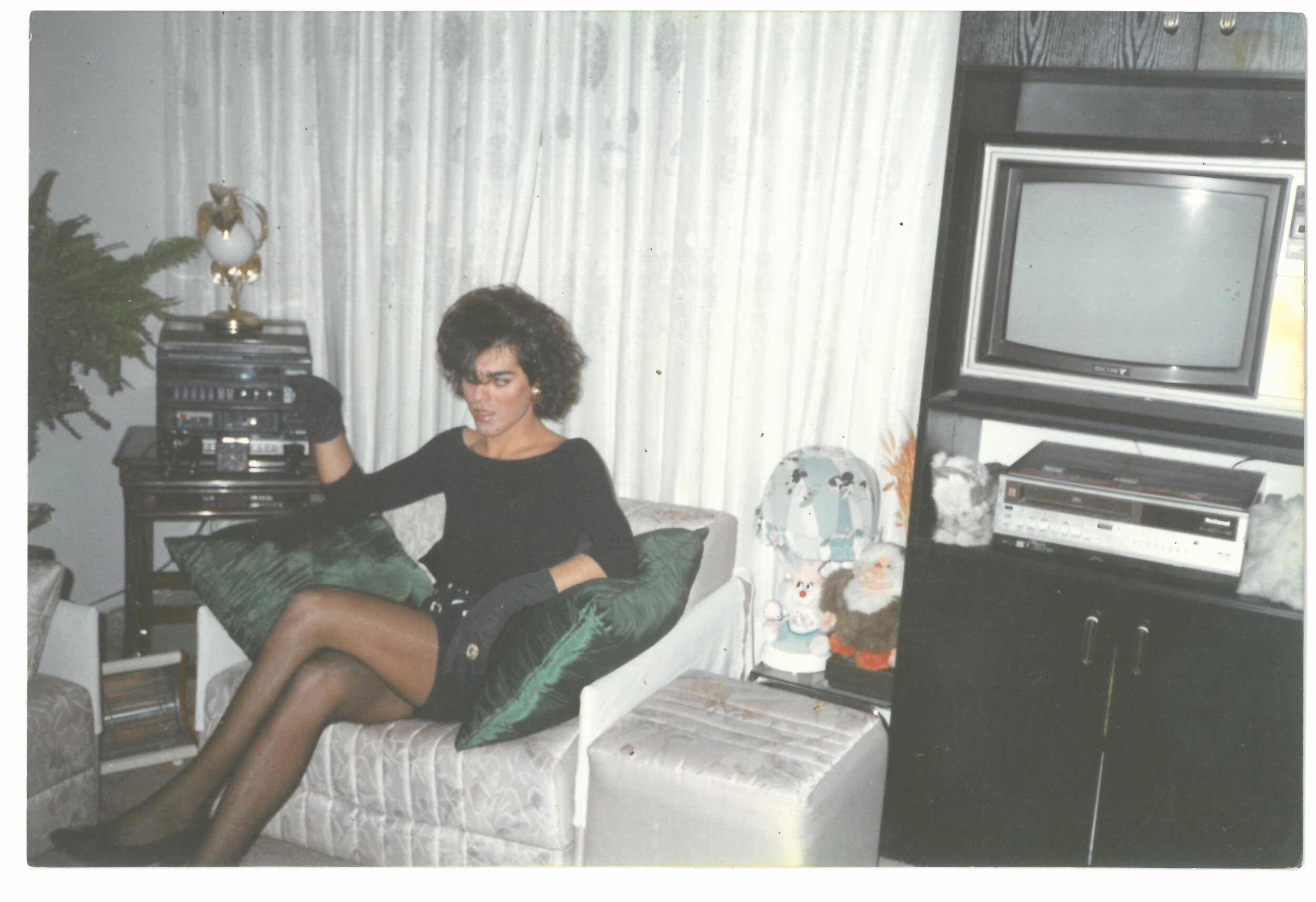

Over the course of two weeks in July 2019, we met with each woman at a studio in cultural space Station Beirut, where we conducted interviews before individually tailored portrait sessions where they had at their fingertips a team that would pamper them and offer to glam them up the way they wished, with a large selection of outfits they could choose from. We were introduced to everyone by Helem’s Mamma Jad, to whom we are all indebted. The people she selected are part of a community, and know many of the others we spoke to. We were all deeply impacted by the ladies we spoke to, and want to convey our deep respect, gratitude, admiration and affection to them all. Our team are all very familiar with queer communities in Lebanon. Despite this, we were completely astounded by the stories we heard, most of which completely reframed our understanding of Lebanese queer cultures.

Mama Jad, from Treat Me Like Your Mother

This project will result in special edition of Cold Cuts, which will be published in the Spring of 2021, with support from LGBTQI+ NGO Helem, the Arab Image Foundation, and culture space Station. I sincerely hope we are able to raise the funds and publish this important work.

JTD: I hope so, too! Aside from this publication, what else are you currently working on? What’s on the horizon for you as an artist?

MA: To be honest, aside from this special edition issue, I’m also working on the second official issue of Cold Cuts, but that’s about it for now. The current state of the world has put work on a hiatus at the moment, but I’m glad I get to pull all of my focus and energy on these two publications for now.

As for what’s next, I honestly have no idea!

JTD: Great, thank you so much Mohamad!

Production still from Treat Me Like Your Mother

All images © Mohamad Abdouni