Q&A: nicole white

By Jess T. Dugan | May 3, 2018

Nicole White is an Oakland-based artist, curator and writer. She holds a MFA from the School of the Art Institute of Chicago and a MA in Art History from the University of Connecticut. White uses historical and contemporary processes to examine the functions of photographic images. She has exhibited her work throughout the United States and been published in several academic and fine art journals. Currently, she is an Assistant Professor of Photography at Diablo Valley College in the Bay Area.

Jess T. Dugan: Hello Nicole! Thanks so much for taking the time to speak with me today. Let’s start at the beginning: how did you discover photography, and what was your path to getting where you are today?

Nicole White: Hey Jess! Thanks for having this conversation with me.

I found photography by accident. As a teenager, I had grand illusions of becoming a painter with a studio in an unaffordable part of New York City. In hopes to achieve this wacky dream, I started taking summer classes at AIB and the first one I picked (why, I can’t recall) was photography. I found that the magical qualities of making images – this was pre-digital – felt equal parts technical and impossible. It was that experience that solidified my path to art school. After my undergrad experience at MassArt, I went to graduate school for art history to better inform my practice and to help me gain a broader sense of where the ideas I engage with sat in relation to the rest of the photography/art universe. Then I tried to take that knowledge and use it to expand my work while getting my MFA.

I did not go to graduate school thinking that I would end up teaching; I didn’t know what the future would be. However, the MA program at UConn required grads to teach art history. So I did. I very quickly realized that I enjoyed the role immensely.

School has been (and is) a critically important space for me as an artist. I am constantly challenged as a student and as a teacher. The dialog keeps me on my toes and always looking.

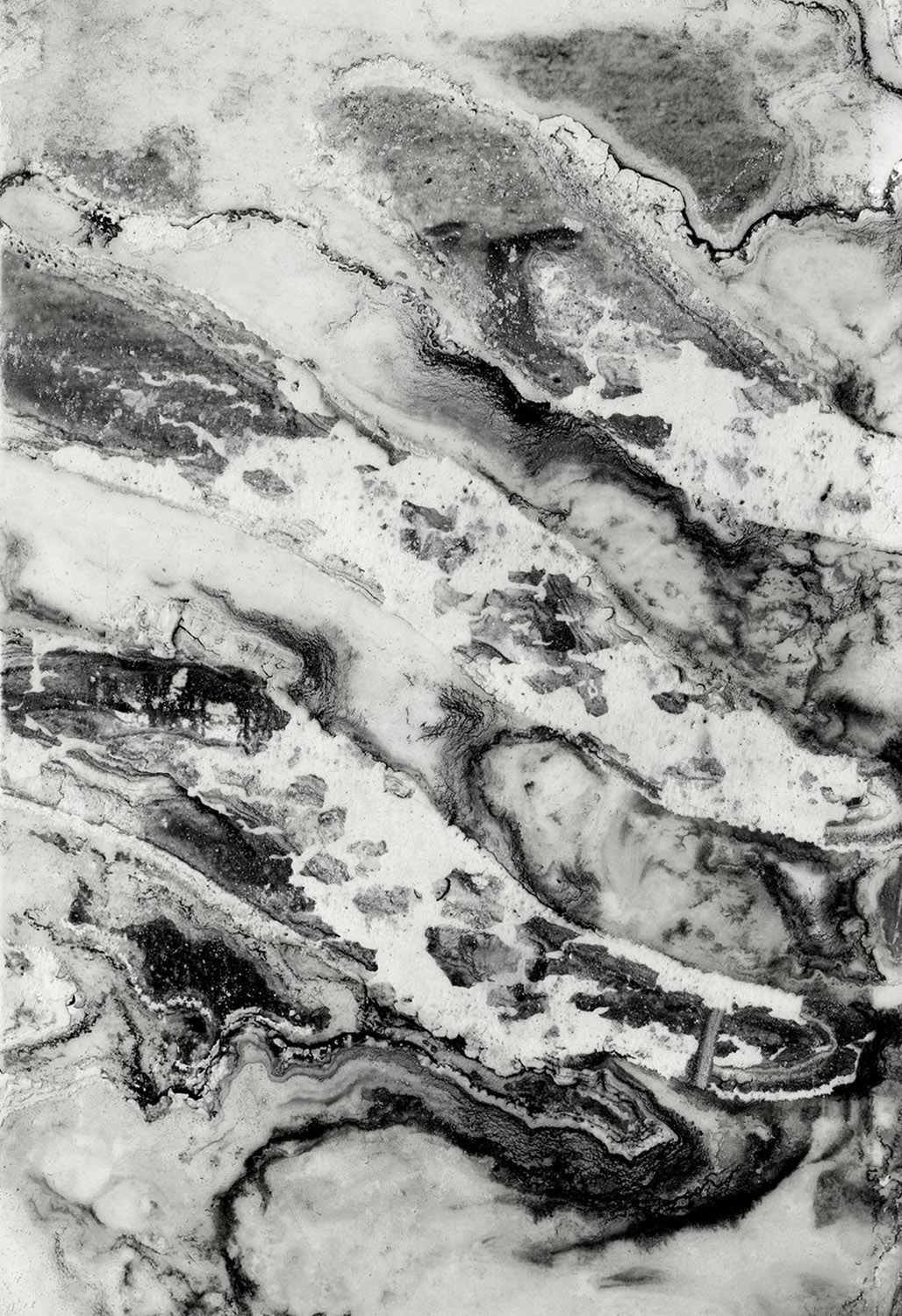

#24 from A Thousand Plateaus

JTD: As I was putting together this interview, I found myself wondering which of many directions we could go, as you have a very wide array of experiences working in the world of art and photography. You have degrees in photography, art history, and studio practice. You have worked in the gallery world and also have an extensive curatorial record. Lastly, you are an educator (and I am sure you are many more things than I have even listed here). How have all of these experiences affected your work, from the perspectives of maker, educator, writer, and curator?

NW: It’s difficult for me to separate those four roles because they overlap in a myriad of ways. Those varied experiences have enabled me to locate alternative modes of expression that might be better suited for whatever it is that I am working on. For example, sometimes the work is not about making photographs but instead finding examples of things that I think are performing a certain task and curating those into an exhibition. Each of my projects has its own distinct parameters and are resolved in whichever mode feels the most appropriate.

I think that’s an answer...

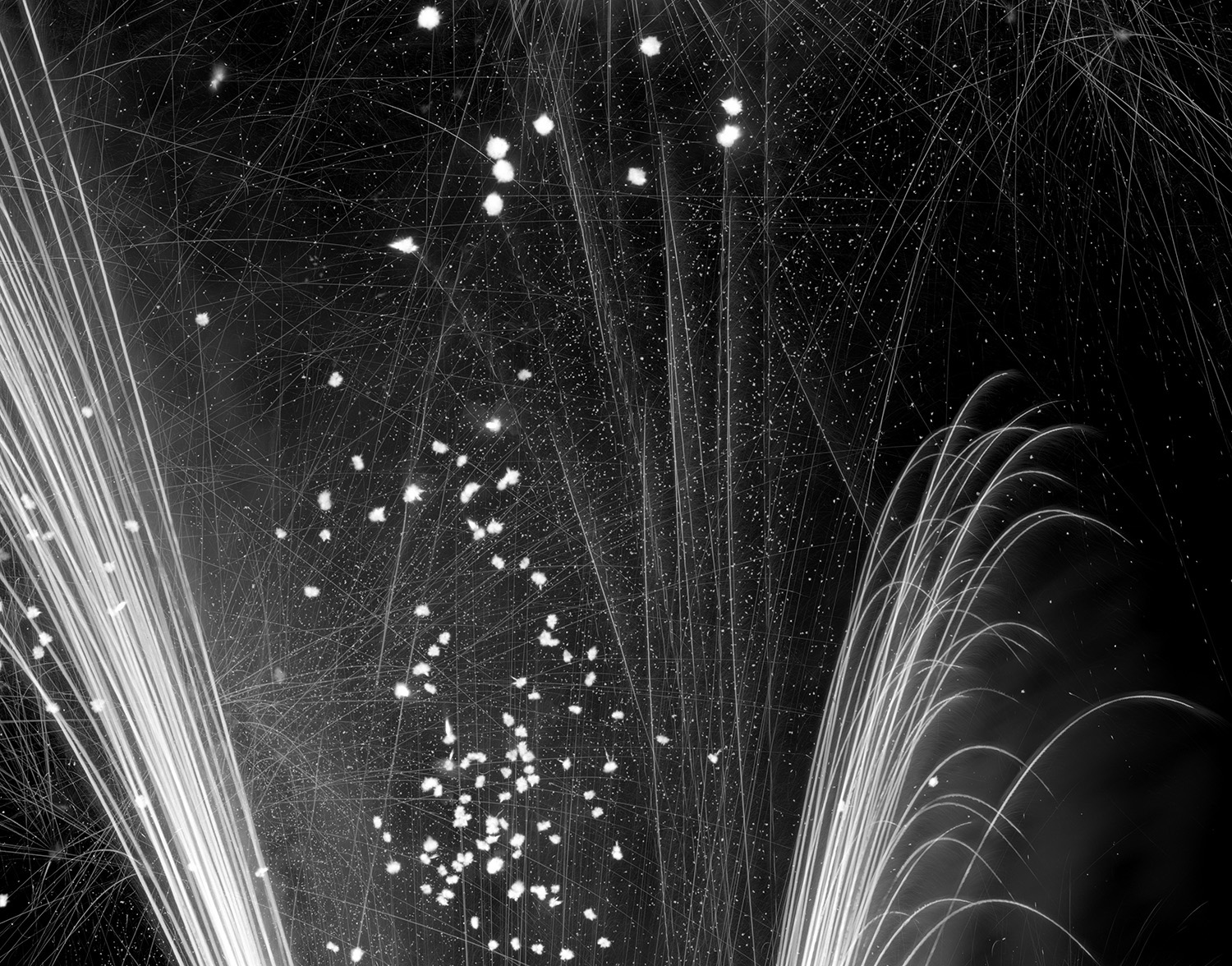

Untitled (Fireworks) from Light Studies

JTD: Indeed! Following that line of inquiry, in your artist statement, you write, “I'm never sure if I am a photographer, yet I work solely with photography. Its complex relationship with art and commerce, its democratic nature, and its proliferation throughout society in a multitude of forms are what keep me actively engaged with the photographic image. Perhaps I am a photographer at some level, but I've never been able to define where I stand in relation to the medium. I'm constantly shifting my position... or maybe it is. I think 'off' the photograph in hopes that the image becomes clearer.” The idea of working with photography but not identifying as a photographer is so relevant at this particular moment, particularly as we have witnessed an explosion of photographs and imaging technology. And yet, photography still struggles to compete with other art forms in the contemporary art world and market. How do you grapple with these ideas? How do you situate yourself in relationship to photography, both as a process and as a “world,” if you will?

NW: I’m going to answer this in a couple parts:

-I am definitely a giant, nerdy photographer. There’s no way around it. I just don't always know if I’ll succeed, hence the hesitation to commit to the title.

-I see the “artist working with photography” vs. “photographer” dilemma as a strategy to upend the historical understanding of what a photograph is along with potentially creating a type of photographic image that can compete within the realm of contemporary art. By using photography in combination with ideas pulled from painting or sculpture or installation, the work leaves the space of pure photography and becomes another thing, right? There are plenty of precedents that used this model, so it’s not as if this is changing photography as we know it, but technology helps to produce new (and compelling) iterations.

-I feel like “working with photography” sounds like there’s a contractual agreement with the medium. As if you’ve talked it over together.

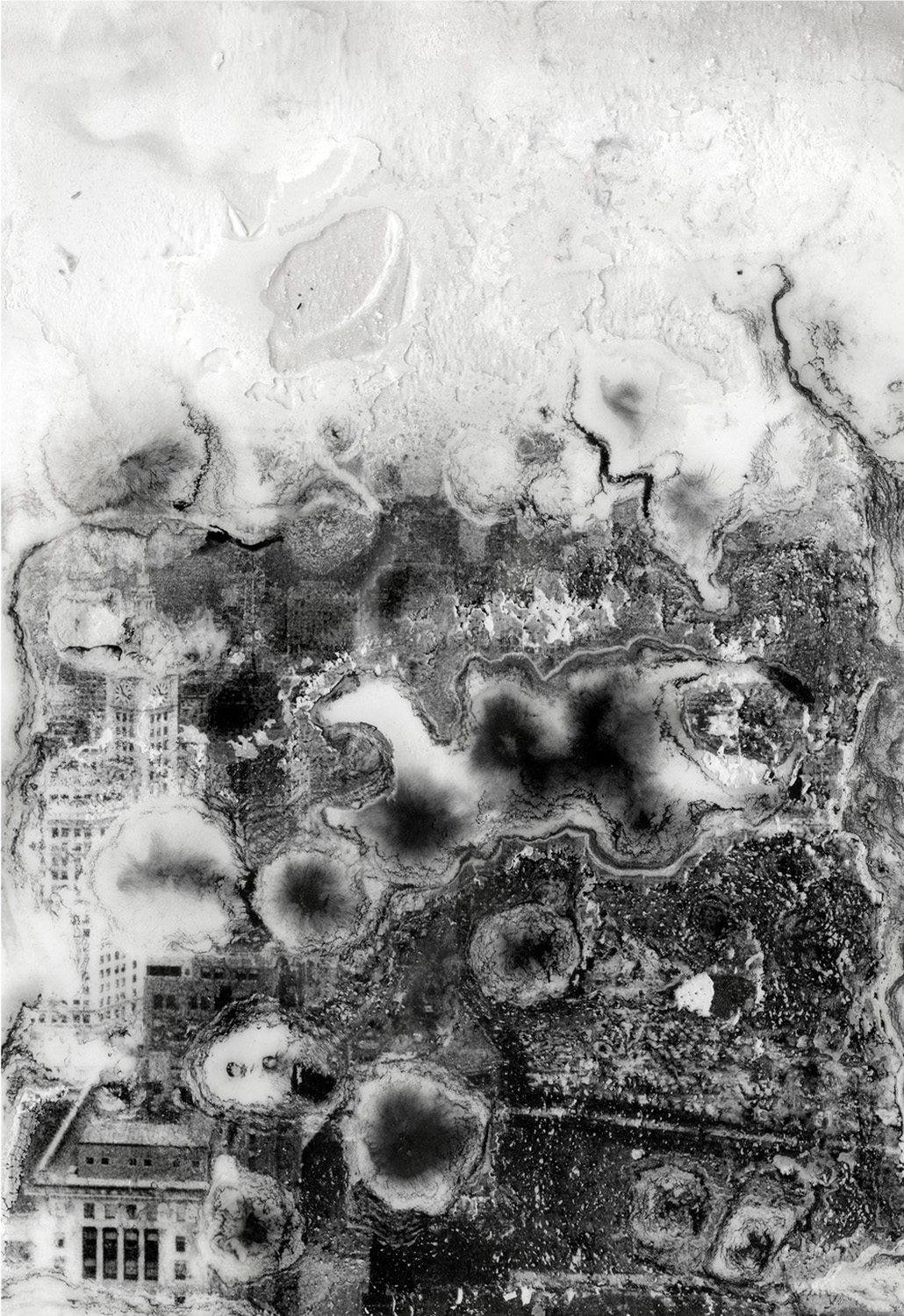

Sun #7 from Light Studies

JTD: In much of your work, process is essential, whether this involves introducing the elements of weather and time, as you do in your series Dissolution, or whether it is your engagement with materials in your series A Thousand Plateaus. How significant is process to your act of making?

NW: Process is always significant, no matter what I’m working on. I change my process based on what I’m thinking about. For example, A Thousand Plateaus was my first attempt at making pictures of nothing that become something through the act of trying to decipher them. I still make work with this undercurrent, but I have tried to pull the concept out from studio based images and apply it to my surroundings.

My process shifts pretty drastically from project to project making each body of work fairly different from the next. The way an image is seen/experienced is as important as the image itself.

JTD: Given that each project is so different, how do you set parameters for yourself? How do new ideas come into being, and what is your process for seeing them through to completion?

NW: I used to set incredibly stringent parameters for my work until I realized that I wasn’t allowing myself any sort of happy accident or discovery. Now, I’m much looser and allow for experimentation, but I still try to keep the initial concept at the forefront. I spend a lot of time looking at the world around me for anomalies that I want to either photograph or attempt to reproduce on my own.

This is a delightfully frustrating question because seeing things through to completion has been a huge challenge. Over the past eight years, I’ve moved to multiple cities across the country while in grad school and working as an "itinerant academic". I’m starting to think in much longer terms with my projects because I can’t always work through an idea as quickly as I would like. Now that I'm settled on the West Coast, I like to think that I will develop a more structured studio schedule.... We'll see....

That said, I did complete a small project this past fall entitled Redux. It was a visceral response to the photography program that I now run. I made images as I was reorganizing the lab and encountering all sorts of photography relics. I felt completely overwhelmed and weirdly incapable of parting with these objects, so I made a variety of image types that attempted to best capture them before I determined if they should be discarded or kept.

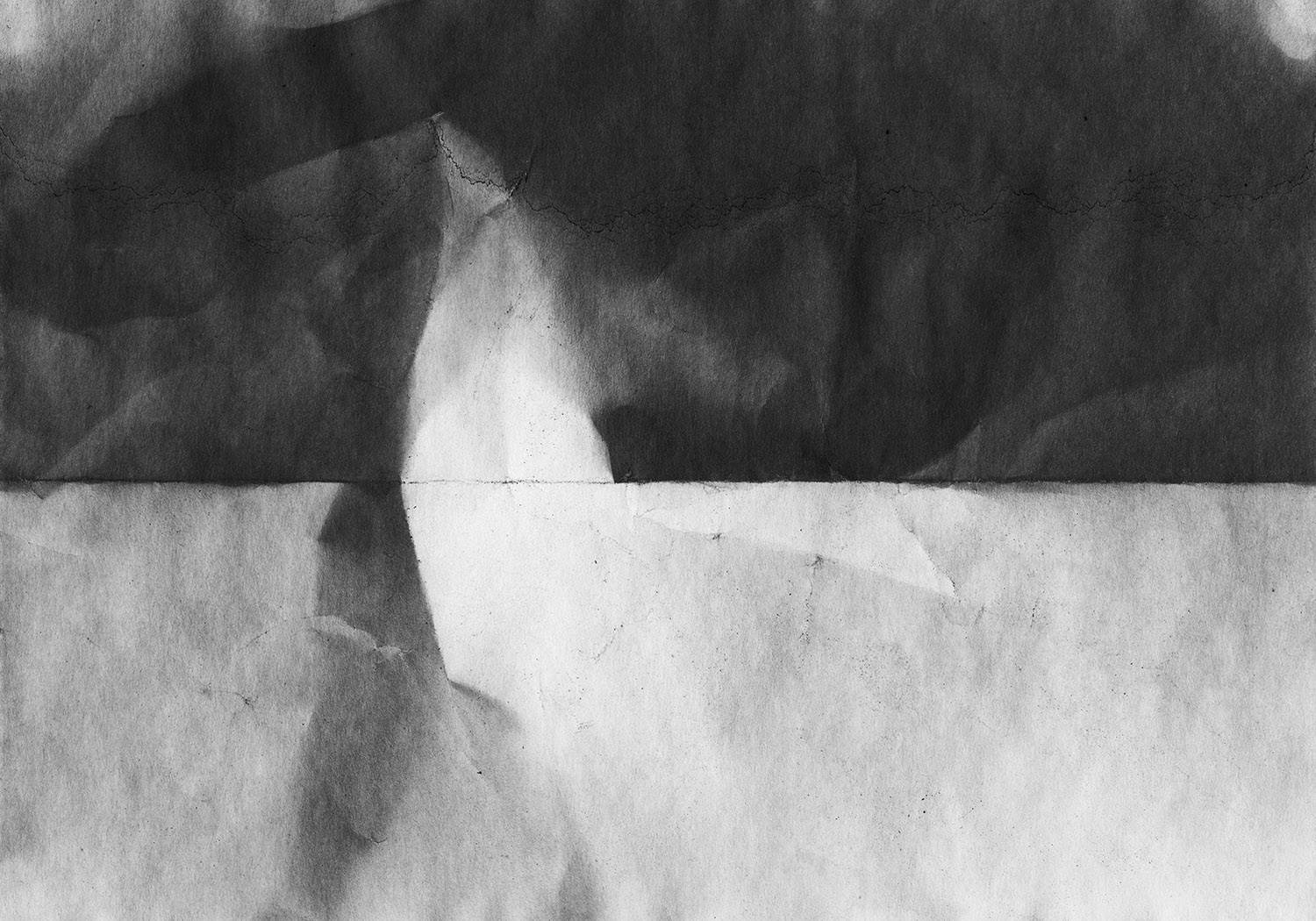

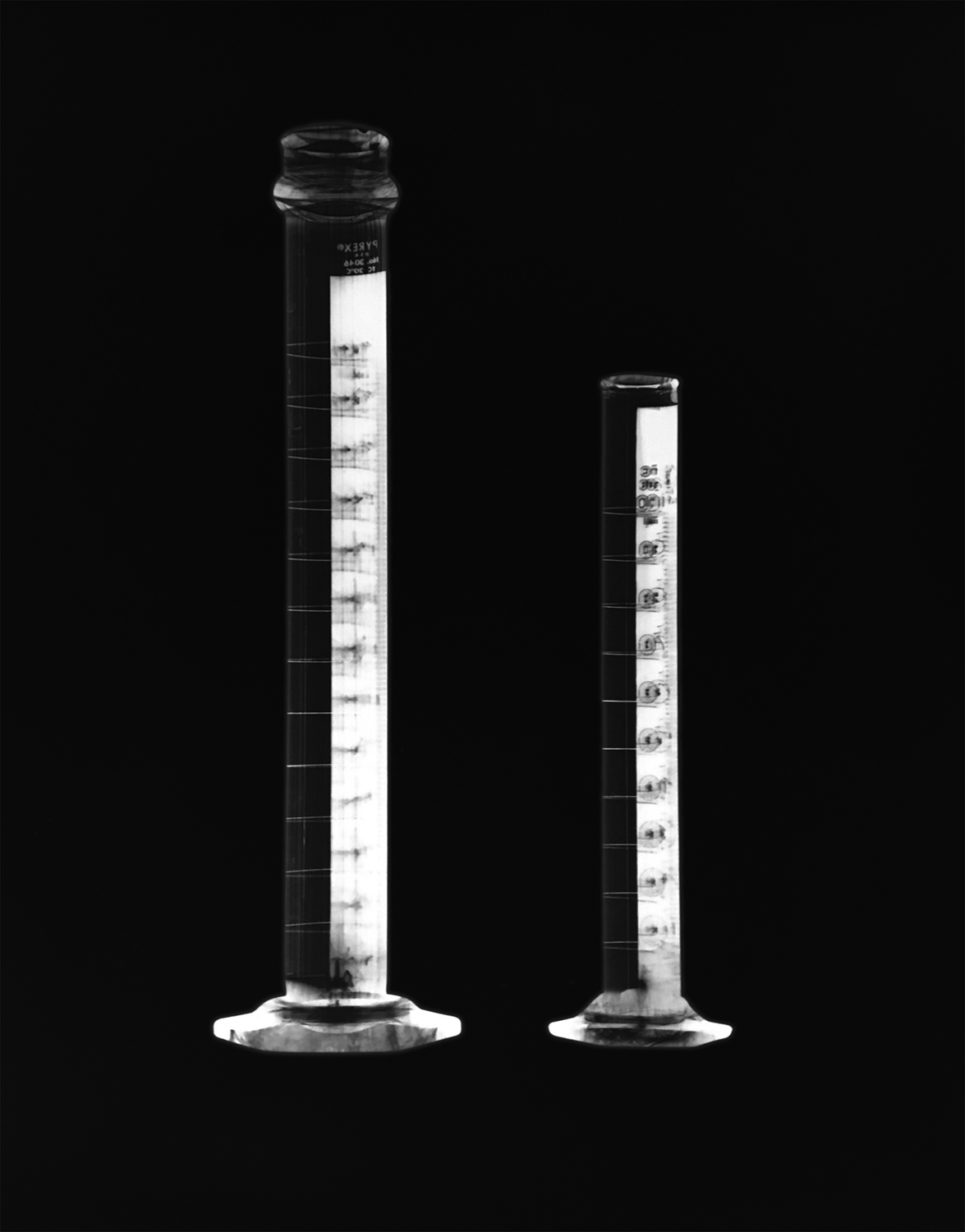

Safe Light Still Life from Redux

JTD: Another theme that runs throughout your work is the idea of place, both the individual and collective experience of it. Your series A Thousand Plateaus, you write, “is the result of an investigation of traditional compositional tools and how those tools are perceived. Through picking a familiar subject matter (landscape) and creating a photographic image reminiscent of that imagery, the photographs illustrate how ingrained certain modes of looking are in contemporary society. The photographs are created through multiple camera‐less processes employing the most basic tools: sun, water, soot, silver, paper, and glass. Stripping down the photographic process to these elements allowed for the introduction of my hand in the work. The resultant images are of my own making; there is no ‘actual’ place. The images then raise questions regarding what is actually being depicted.” What is your relationship to place in your work? How do you grapple with creating a sense of place that might not actually exist, while also, in other projects, abstracting actual space to create images that go beyond representing a specific place?

NW: Landscape is where I started as a photographer. I traveled around the country for years making landscape photographs that had certain histories I found compelling. I got to a point with the work where I found that physically being in the place was more crucial for me than the making of the image. So, through a reductive process and more studio-based work I determined I could make images that hinted at place without a need to be a direct representation - thus not failing to represent the "real".

JTD: You mentioned this a bit earlier, but since I have known you, you have lived in Boston, MA, Chicago, IL, Louisville, KY, and you are currently living in Oakland, CA. Do you think that your work is influenced by these different locations, and more specifically, by your personal history of not being rooted in one specific place?

NW: Moving repeatedly has made me hyper-aware of the stark disparities in each place I've lived. There are little things I notice, like how the way the light has changed. The light here is decidedly different than that of the East Coast or the Midwest. But then there are more critical elements, like that of income inequality and the collision of nature and civilization. These were apparent to me while residing in Chicago and Louisville, but even more so now that I live in one of the most expensive regions of the country. My work is slowly beginning to depict a dialog/critique about the state of the country while still thinking about more abstract photographic concepts.

I’ve been working on a project for the past few years that is a very direct reflection on my migration across the country. It’s titled iamhereinthisplace and the images are a quiet inspection of my surroundings with a suggestion of social commentary. I have kept it to myself because I didn’t know where it fit within my larger practice. However, I’ve finally begun to tether my more experimental work to images made out in the world and am seeing how the pieces can fit together.

JTD: That’s a great segway to my final question: what are you currently working on? What’s on the horizon?

I'm working on the aforementioned project along with other smaller experimental works. Soon I'll update my website and the new work will materialize on the Internet, but for now I'm still keeping most of it under wraps until I have a better grasp on it.

In other news: In 2017, I joined up with a group of amazing women (Danielle Ezzo, Ina Jang, Anastasia Samoylova, and Brea Souders) to form DOMMA Collective. We function as a collaborative entity, a support group and a sounding board for each other's thoughts and ideas. We've made a point to meet in person twice a year to produce work together and promote our individual projects. It has been a particularly unique experience for me as I have never worked collaboratively and I've had a few realizations about my work and about other artist's approaches to art making. We will have work from our last meeting out in the world in the near future, hopefully this year.