Q&A: Renluka Maharaj

By Hamidah Glasgow | February 6, 2020

Renluka Maharaj was born in Trinidad and Tobago. She lives and works between Colorado, New York City, and Trinidad. Working with photography, installations, research, travel, Ms. Maharaj's work, which is often autobiographical, investigates themes of history, memory, religion, and gender and how they inform identity.

Ms. Maharaj completed her BFA at the University of Colorado Boulder and her MFA at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago, where she received the Barbara De Genevieve Scholarship. Her works are in institutional collections, including The Art Institute of Chicago, Museum of Contemporary Photography in Chicago, Joan Flasch artist book collection, Los Angeles Center for Digital Art, and special collections at the University of Colorado Boulder as well as numerous private collections.

HG: Tell me about your trajectory as an artist?

RM: I was supposed to be a lawyer like my parents wanted, but after taking a painting class, I fell in love! I enjoyed the smell, the texture, application, and most of all, I felt a rootedness in the Arts, especially through the use of color. I studied with William T Williams at Brooklyn College in New York, who taught me everything about painting. At the same time, I was painting; I decided to explore photography, which offered a new gateway to creating. After moving to Colorado and attending the University of Colorado, Boulder, I decided to focus more on photography. At my BFA show, the work was controversial but well-received, and I sold 2 of 3 pieces. That same year I started my MFA program at the School of The Art Institute of Chicago, where I not only had wonderful Professors to work with, but I also helped in running Parlor Room, which is a visiting artist program, that gave me access to amazing working artists. After graduating and returning to Colorado, I was fortunate to gain gallery representation with Rule Gallery in Denver. My residencies came after with scholarships to Vermont Studio Center, Virginia Center for Creative Arts, Fountainhead Residency and this year I have two residencies I am excited about: Golden Foundation Residency in Upstate New York and Project For Empty Space in New Jersey, a year-long program which will give me a presence in the New York area.

HG: As your artist statement states, gender, sexuality, religion, and colonial history, are the focus of your work. These are complex, layered narratives. How does the work tell the stories of Trinidad specifically?

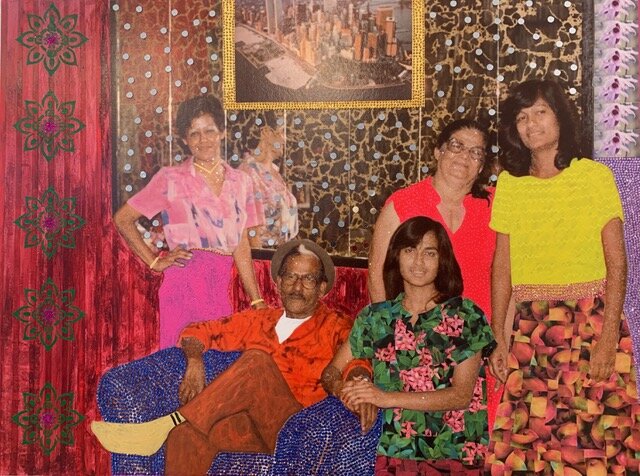

RM: I identify as Hindu and grew up in a household surrounded by images of deities that adorned our house. My mom was quite devout, which has had a significant influence on how I think about my work and the use of color, patterns, and textures. Lord Shiva, in his representation as "Ardhanarishvara" embodying both male and female characteristics, was the influence for my BFA show.

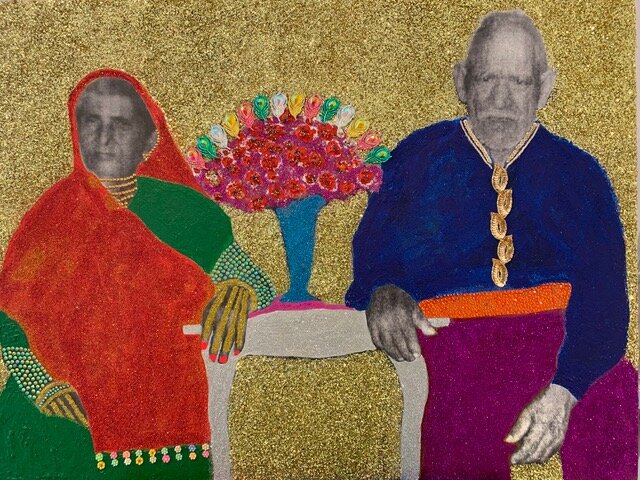

As my art continued to progress, my focus shifted towards a more complex history about my family and idea of home. My maternal grandparents arrived in Trinidad in 1913 as indentured servants under the British to work on the sugar plantations. Like most of the Indians taken, they were from Northern India. Indians were the new labor source as slavery had been abolished, though the conditions they lived and worked under were very similar. It's a history of people that have been violated, enslaved, othered, killed, and raped to uphold a system of capitalism. The British did this globally, but my focus is on Trinidad, where I was born. I grew up in a small village in the south, and my neighbors were of African descent, Indian, Chinese, and Portuguese. There were varied religious expressions and sexual identities.

Growing up as a girl was challenging as I was not one to live up to the roles I saw other Indian women exhibit, one of subjugation. I started to identify more with my brothers as I saw them as strong, independent people. I mimicked their moves and became more of a tomboy, except I was not allowed to wear pants. If Lord Shiva could be portrayed as male and female, why couldn't I embody those qualities as well? Later I learned through the strength of my mother that roles can be broken, and through that, you learn who you are, as she did when she moved from Trinidad, against my Dad's wishes, to New York City.

All of these experiences I try to address in my work. The complexities of existing in a post-colonial land and figuring out one's place within it. Do I call myself Trinidadian or Indian? Is India my home? What does Trinidad mean to me? My family was lied to and seduced into leaving their home to come to a foreign land. They knew nothing of what awaited. How do I love this place? It took me quite some time to call myself a Trini and to fully embrace that no matter what, we persevered and formed our societies and built a place for us.

My work now celebrates this acceptance, and I have elected to showcase the beauty, strength, love, magic, power, and diversity of a people that persist, not perfectly but with grace and intention.

HG: Your images of marriage strike me. As a feminist, my view of traditional marriage is one of subjugation and patriarchy. Tell me about your images of marriage and what they symbolize to you? How do you choose the colors and embellishments?

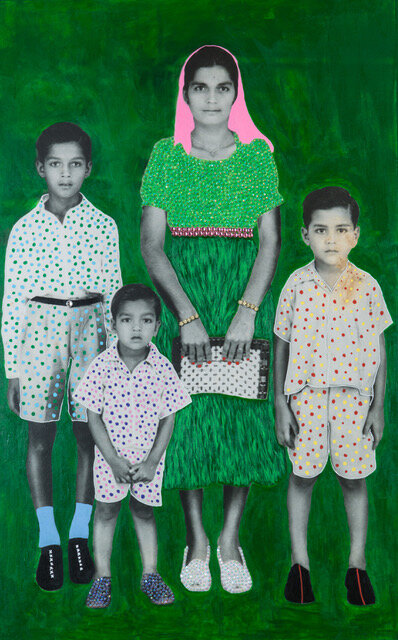

Ties That Bind

RM: Marriage is different for everyone, traditional or not, I try not to generalize. In "The Ties That Bind," it illuminates my brother's wedding in 1978 in Trinidad at the family home. This particular scene depicts the entrance of the bride into the groom's house, where she is welcomed and blessed. The cloth that binds them symbolizes the unity of the couple and their promises to each other to walk together through life, which I find comforting and warm. However, most of the time, from my own experience and those of my sisters and mother, marriage is far from the beautiful rituals. The "pomp and circumstance" that is a Hindu wedding seems more about the community than the couple, lesser so the bride. She leaves her family and enters into a new one where she becomes a caretaker, and her desires are second to everyone else's. This is not specific to Hindu marriages as I have many friends who have had non-traditional marriages, and the outcome can be the same. Saying this, for me, marriage is more complex. My sisters told me they were forced to marry because our Dad thought they were exhibiting signs of blossoming sexuality that he needed to control. The control of women's bodies continues, e.g., in this country presently, the ongoing debate of a women's right to choose! I have two daughters, and they are free just to be themselves. I couldn't imagine anything else for them. They are light years ahead of me at their ages. That's progress, and I wish that for all women.

As far as the colors and embellishments: I exaggerate existing colors present in the photographs, or I reference the colors of religious iconographic imagery. Because I know the people in these images, I remember their personalities and play to that.

Wong’s Studio 1943

HG: How do you manage the role of being a woman and an artist? Society still has relatively narrow avenues for women.

RM: If I focus on the lack of place for me within society and the art world, I would be frozen! I come from a culture that had narrow avenues already, and I constantly fought against that. Was I punished, yes! But that just gave me more of a reason to continue fighting, as I do now, especially being an artist of color. We all have stories; I don't feel my struggle is so different from many women. I continue to cherish and understand where I come from and where I am going. My hope is for my work to be appreciated through exhibitions etc. as I want more people to know about this history and its people.

HG: Tell me about your most recent work and its motivation?

RM: The motivation for my recent work started a few years ago after taking a DNA test with 23andme. That just got me thinking about my family's history, and I wanted to know more. I thank God I am an artist because I feel strongly this desire to find out about my past would not have happened. As an artist, I am constantly looking and evaluating who I am and that history is a big part of this puzzle.

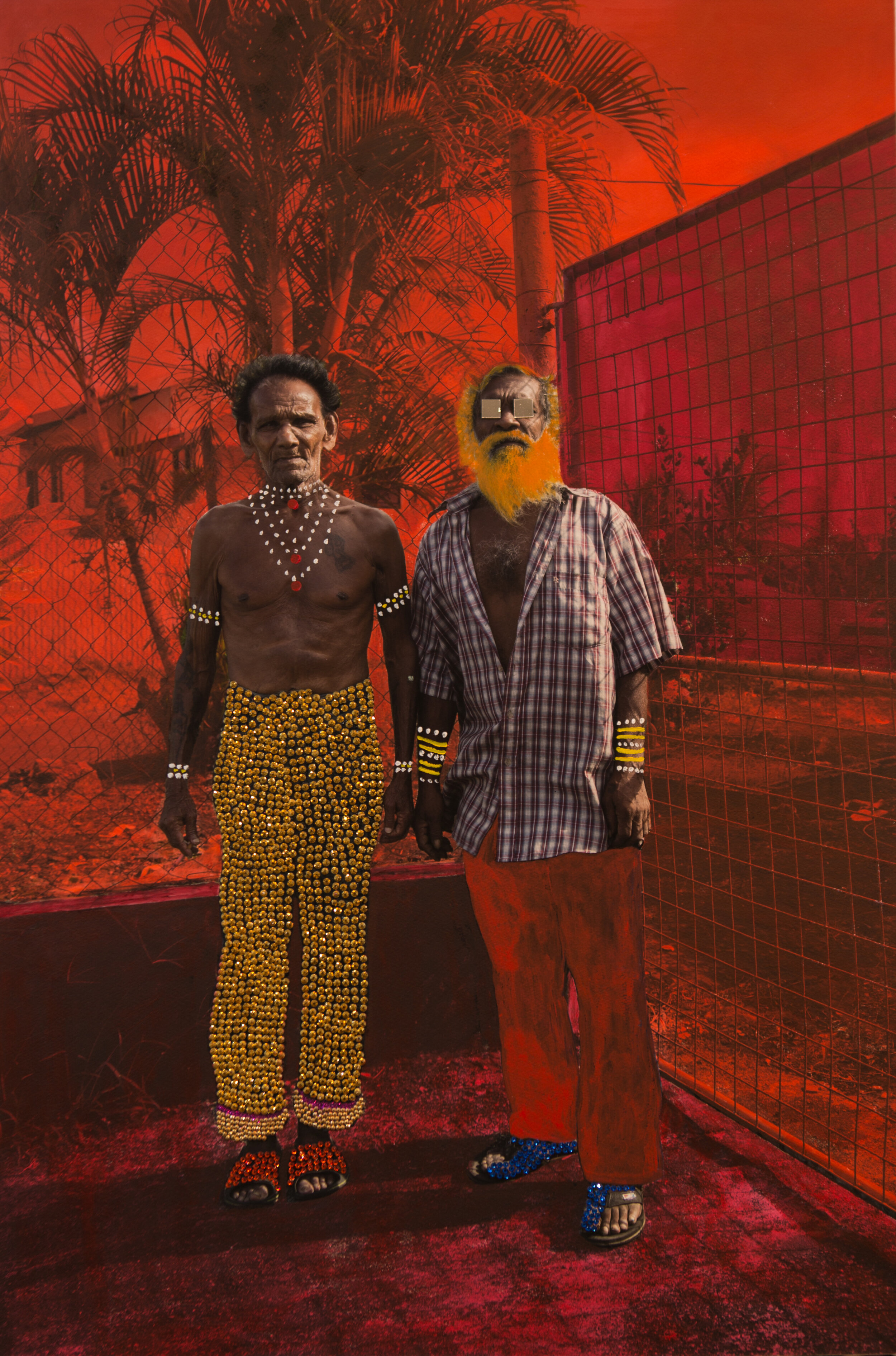

For me, it became important to speak about a little known history of Indian Indentureship. Over one million Indians were taken out of India under the British and sent throughout the world, and so little is written about it. Being a visual artist, I want to bring attention to this but also highlight the tenacity, endurance, and beauty.

HG: Tell me more about this: Over one million Indians were taken out of India under the British and sent throughout the world, and so little is written about it. Being a visual artist, I want to bring attention to this but also highlight the tenacity, endurance, and beauty.

RM: Indians are one of the most dispersed groups around the globe. With slavery being abolished in the mid-1800s, Britain needed a new system of slavery; Indentureship and India would help with that. They needed the machine of productions for goods like coffee, sugar, tea, and cotton to continue cranking to uphold their domination. The indentured laborers could hardly read or write, they would place a mark (most likely fingerprint) on a piece of paper giving up their lives for 5-10 years without knowing where they were going, how long and the conditions under which they would work. All they knew is that they were going to work, earn money, perhaps become wealthy and come back home. Many died on the months-long voyage from disease and starvation, including children. The British considered the' natives' to be ignorant, uneducated animals; therefore, their lives were not important. There was concern in the Parliament, but those voices were quashed by the influence of the Plantocracy. The first shipment of over 75,000 Indians left for Mauritius. The first ship to the Caribbean left Calcutta carrying 400 Indians (now called Coolies) to South America. Specifically, Demerara (British Guiana), where it was said the best sugar grew. After landing, they were registered, deloused, numbered, and made presentable to the Planter. They lived in existing shacks the slaves once inhabited, or tin shacks were made for them. Cholera, malaria, and typhoid killed hundreds at a time. Mortality rates for very high due to unsanitary conditions. They would beat and shoot the "coolies" at will without consequence.

Over 239,000 were subsequently sent to Guiana to work on the sugar plantations. Over the next 80 years, Indians were shipped to every corner of the British Empire. (South America, Caribbean, Mauritius, Ceylon, Burma, Malaya, and the South Pacific and then South Africa to work on the railroads, mines and sugar fields). My grandparents arrived in Trinidad in 1913 and worked on the plantations until the end of Indentureship in 1920 (thanks to Gandhi). The last ship that came from India to Trinidad was in 1917. It's a long history and one I wish to investigate closer, which I will be doing on my year-long residency. I hope to interview as many Indo-Caribbean people I can and document their stories and do some portraiture as well. I wish to highlight the tenacity, endurance, and beauty of a people that have gone through so much, yet they continue to smile, love and celebrate life. Representation matters, and I want to take control of my own narrative.

HG: Thank you for your time and for sharing your work.

RM: Thank you!

All images © Renluka Maharaj