Q&A: sarah Sudhoff

December 27, 2018

Over the last ten years my work has consistently interwoven themes of gender, science, and personal experience. I am fascinated by topics that seem at first commonplace and ordinary. Yet through photography – both staged and found – I highlight our lack of understanding of such familiar subject matter.

In the last year, my work has turned to breastfeeding. The politics of breastfeeding has recently become a contentious subject, fueling strong emotions, as well as a host of new scientific studies and reports in the press. In early 2013, I created a video documenting a private performance involving frozen breast milk, entitled Surrender. My work stemmed from my inability to produce enough milk for my then-young son. The milk serves as both subject and a metaphor for the feelings of loss and failure that I and so many other mothers have experienced. My work, then, explores a political question through the lens of deeply felt bodily experience.

The intersection of abstract, statistical investigation and affective presentation underpins the way in which breastfeeding is both highly medicalized and yet undeniably personal in contemporary American culture. – Sarah Sudhoff

Breastfeeding is one of the most natural actions a women’s body does after giving birth to a child and yet breastfeeding is fraught with problems. These problems stem from our current social climate towards women’s bodies in general and in particular to breastfeeding.

HG: Tell me about the impetus for this project?

SS: I was sitting in my vintage mid-century gray upholstered rocking chair breastfeeding my son, counting the small white stains on the fabric, on the armrest and the floor around the chair from the past several months of breastfeeding and bottle feeding. These drops to me were reminders of milk lost, nutrients my son wasn’t receiving and a seemingly failed attempt to breastfeed as much as I would like to. I was limited in my bodies ability. No matter that I ate organic food ran, practiced yoga, didn’t smoke drink or have caffeine during pregnancy or after–my body was only capable of so much. It was a hard realization and one that is so deeply personal. As a new mother, you want to provide, care for and protect. And I felt that I had already failed this not even 9-month-old baby. While rocking my son, I finally let go. After months of worrying and months of struggle, I knew that I would have to begin to supplement my breastmilk with formula. My flow was reducing and my supply almost gone. At eight months it ran out. In those final days of breastfeeding, I surrendered.

It wasn’t until nearly a year later when I became pregnant with my daughter that the performance came into being. Surrender was the first piece created for Supply and Demand. Although I am trained as a photographer, this bodily experience I felt couldn’t be properly articulated to others without it being a live experience. It was an image in my mind that I had seen and replayed over and over again. The preparation for the performance came together in a matter of weeks. I was fortunate to obtain donated breast milk from a good friend. I hired a team to capture the performance, selected the site and went for it. We did the video in one 45 minute take, no rehearsal. It was my first time to perform in front of others, a liberating and profoundly spiritual experience. Enough time had passed from my first breastfeeding experience that I was able to reflect on those challenges and emotions during the performance with the very real understanding, and I would face them again with my second child.

In my birthing class we prepared as best we could to expect the unexpected and practiced through different exercises, mind over matter. In one exercise, we were asked to hold frozen ice cubes in our hands and learn to focus our attention elsewhere and to turn the pain into something useful and/or reassign the feeling of pain as something else. I struggled with this exercise–I hate cold water. Ironically when I was considering how to represent the pain of breastfeeding, the disappointment of running out of milk, the expectations put on me and those I assigned myself, the ice exercise encompassed all of it. Frozen breast milk was a metaphor for the experience and also the subject and object which caused me the pain to begin with.

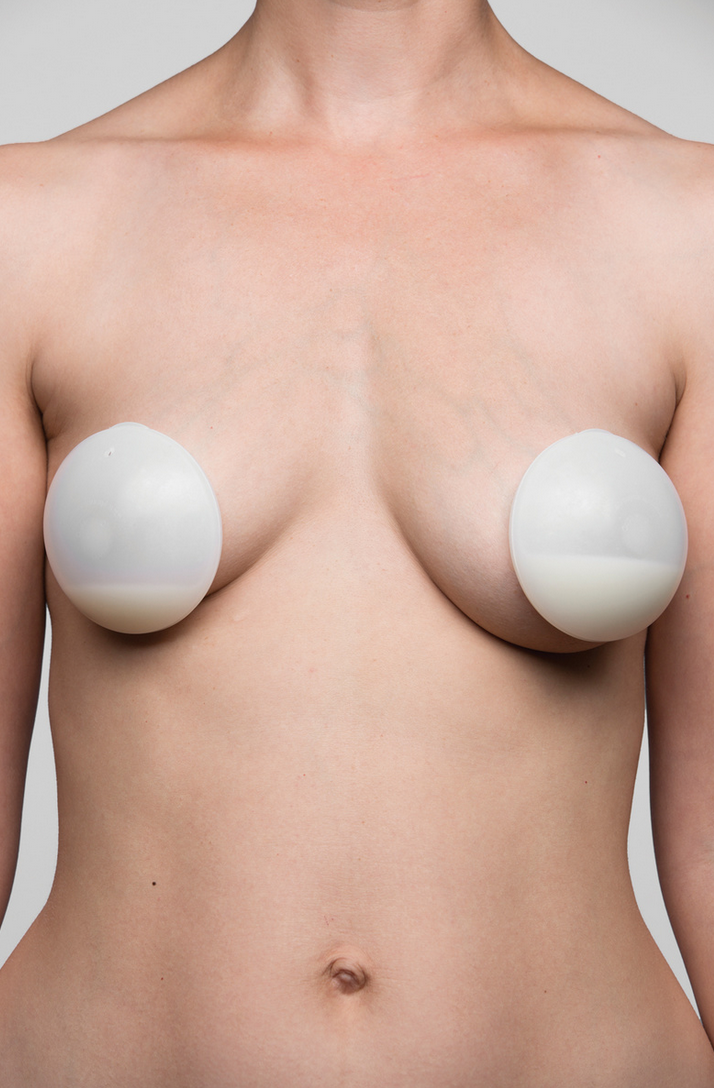

In the Surrender performance, I hold 24 ounces of frozen breastmilk. The shape is produced by the freezer bags that you can use to store breastmilk in. The frozen blocks are cut away from the plastic sheath and held against my breasts and body, similar to the way I held my children when breastfeeding. The heat from my body slowly melts the milk, it begins to drips over my arms, hands, belly, lap, legs and finally pooling onto the floor. When breastfeeding a child, there is no sure way to know how much milk has been released. In this reflective performance, I watched my efforts to melt the milk. I could see just how much I was able to thaw. It was as much a performance for an audience as it was for myself. The milk symbolized both the thing I was unable to do and the feelings of isolation and sadness I had experienced with breastfeeding.

At the end of 2013 just after my daughter was born, I won an unrestricted Tiffany Grant. A month later I resigned from my full-time teaching post. Knowing the struggles I encountered with breastfeeding the first time, how difficult it was to pump at work, teach, and care for one child the idea of caring for two and working full time seemed harder than it needed to be. I pulled my son out of daycare and raised both my children at home for a year. This is not something I would have ever thought I would want to do however given my own struggles and my desire to support my children the best I could in those early years, this was the decision that seemed best for the kids and me. Opposite to my son, my daughter would never take the bottle. I tried countless times. I even went on a 24 hour trip to LA for an artist talk and exhibition opening. She didn’t eat while I was away. She preferred only the breast. Many of the struggles I experienced with my first child in terms of breastfeeding were alleviated by staying home, although new ones arose as I was caring for two small babies at once. Luckily my supply of milk seemed to be a little better this time around. However, I was only able to breastfeed for nine months, one month longer than with my son.

It was during this time of raising both my children at home, slowing down in terms of the demands on myself, that I was able to reflect on the first experience compared to the second experience. I began to create the Supply and Demand exhibition. I looked at the various experiences I had in the beginning and how they had or hadn’t shifted. The project is still deeply rooted emotionally with the first child however I used my post pregnancy and breastfeeding body from my second child in the series.

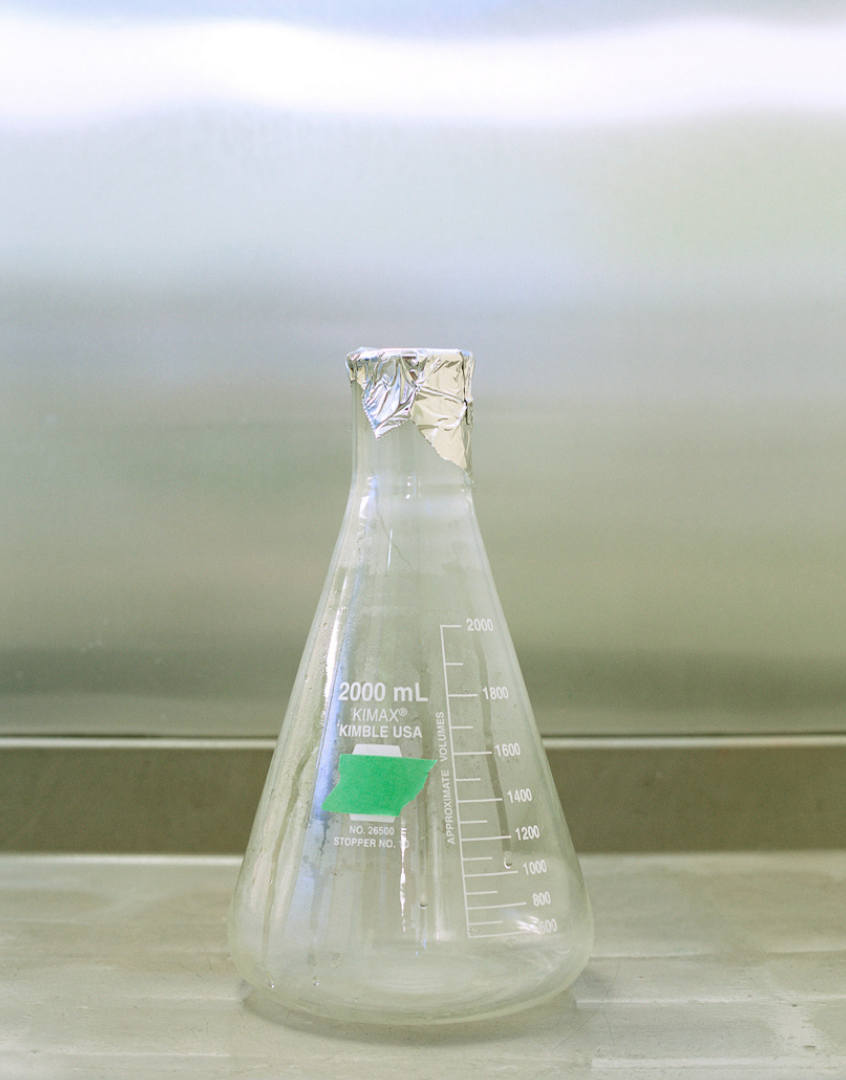

Right away, I struggled to sufficiently and adequately breastfeed my son. I visited lactation consultants a number of times to assist me in latching my son’s mouth on to my nipple. It sounds simple enough however it can be a very difficult maneuver for mother and baby. The consultants would weigh him upon arrival and then after feeding to see what I was able to produce. Women almost always produce more milk when its a mouth to nipple contact rather than using a pump. Latching was difficult so much so that my nipples were cracked and bleeding. I was advised to pump milk to allow them to heal. The milk was pink., although I still feed this to my son, albeit through a bottle until my nipples healed and I could resume breastfeeding. This was my first introduction to the pump in the first days of given birth. I also was advised to pump in between feedings so that I could produce more milk and save it. Unfortunately, my supply was low from the beginning and didn’t really increase. I returned to work at six weeks, not because I wanted to, but this is all the time I was given. My body was still healing, and I was beyond exhausted. Therefore pumping became a way of life for me. I had to wake early in the morning to pump before leaving for work and before a scheduled feeding to leave enough milk to last my son until I got home, 8 hours later. I only ever had enough milk, nothing extra. I would pump while at work to save for the next day of feedings. It felt like a vicious cycle. One that I can never get out of yet was destined to stay in for the foreseeable future.

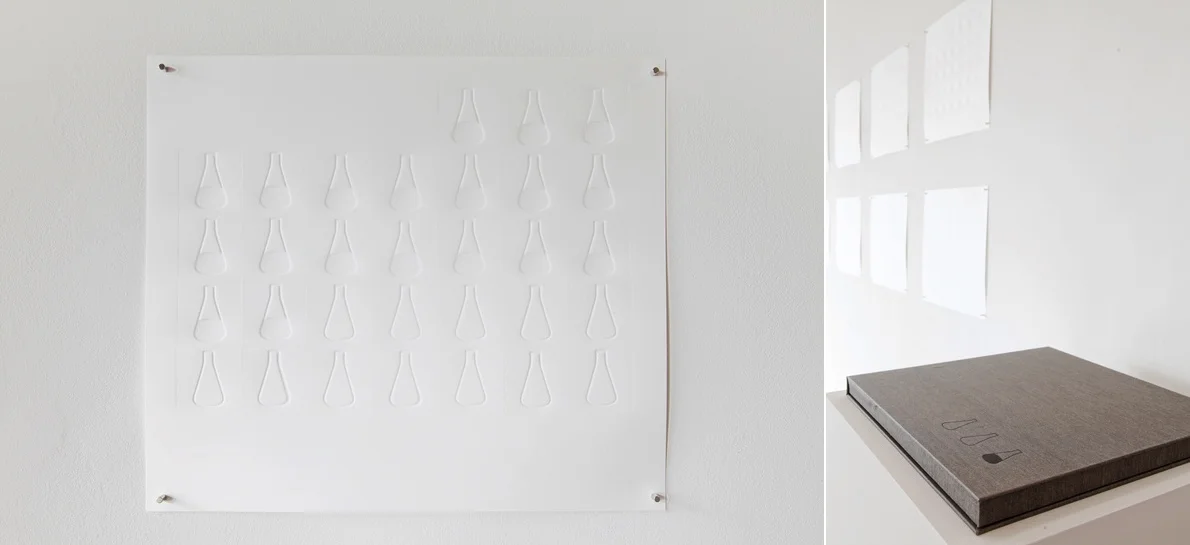

Failure of the Ordinary, 2014

HG: Women who work outside the home and are breastfeeding encounter a myriad of issues, tell me more about those?

SS: I was teaching full time for an institution. There were several women on faculty however nothing had been put in place for pregnant or breastfeeding instructors. I had to ask for a place to pump and store my breastmilk. Luckily I was accommodated fairly easily, but since my classes were four hours each, I had to pump before, during and after each class. I could feel the urge to pump yet had to wait for a break or the end of the class. Unfortunately, as a result of delaying the release, this would signal to my body to produce less milk. A fact I was aware of, which caused further feelings of anxiousness.

When my son was five months old, at night he woke every hour on the hour. As an already sleep deprived and exhausted mother, this new situation became unbearable. Driving to class one day, I nearly ran into a telephone pole. At the time, I had an amazing female supervisor who saw the concerns on my face. I wanted to continue to work and be an effective and engaging instructor, but it just wasn’t possible for the moment. I was able to drop to part-time, lose my health benefits but finish the semester. In these early months, I was so envious of long-term maternity leave practiced in other countries and those friends who were able to determine their own length of maternity leave. The system and structure in the United States are in no certain terms cruel. In six weeks-the average length of maternity leave in the United States, my breasts were still bleeding, my episiotomy incision still raw (took nine months to heal), and my body drained emotionally and physically from a 27-hour delivery and all night feedings.

In addition to the physical issues, there were psychological issues that arose. Rather than being at home, breastfeeding, resting when I could and seeking the advice, support, and counsel of friends and family, I was at work completely removed from the environment meant to nurture my child and myself. I remember participating in a discussion about breastfeeding and raising children. The audience was filled with women in their 60’s and 70’s. As I described my struggles to breastfeed and to pump enough before going to work, they commented on how none of them had ever pumped; they didn’t even exist at the time. Instead, women in the neighborhood would gather for feeding circles, support each other with food preparation, childcare, and laundry. And most importantly they create their own community, sharing knowledge and resources–something I desperately lacked.

Tipping Point

HG: What were people reactions to the performance aspect of the project?

SS: The response to the performance is always profound and varied. I honestly think it is the most successful piece in the project and is certainly the one that has been exhibited the most as either a video or live performance. Because I am sitting so still people mistake me for a sculpture and are surprised to find I’m real. In most cases, the audience is somewhat reverent to the performance for the first 15-20 minutes, but then a shift happens. They begin to discuss the work, move about me and engage in everyday conversations. Over a 45 minute to 1 hour live performance this wave of observation and participation ebbs and flows many times. During one performance, a visitor stepped in the milk, and I heard gasps from the audience. The milk on the floor was just as precious and sacred as the work on the wall. Some visitors find the work erotic, while others, both men and women are deeply moved by the slow, painstaking effort of the performance.

HG: Thank you!