Q&A: STACY SKOLNIK

By Rafael Soldi | November 14, 2019

Stacy Skolnik is a poet, editor, co-founder and co-curator for Montez Press Radio, and PEN America Prison Writing Mentor. She is co-author of the zine Rat Park with Katie Della-Valle and her work has been featured in Lambda Literary’s Poetry Spotlight, Columbia Journal, The Operating System, No Dear Magazine, Fjords and Adirondack Review, among others. mrsblueeyes123 is her first full-length collection of poetry.

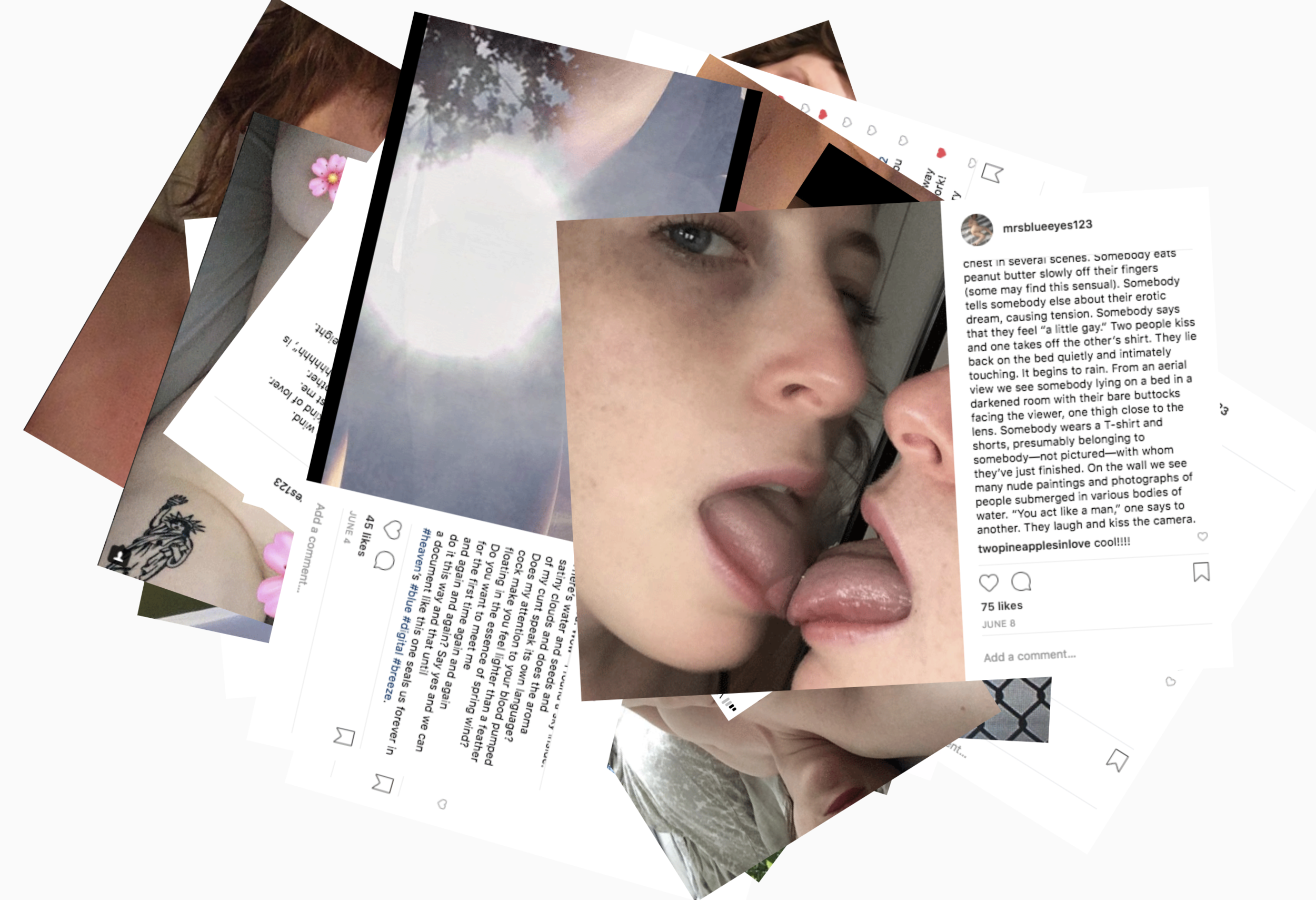

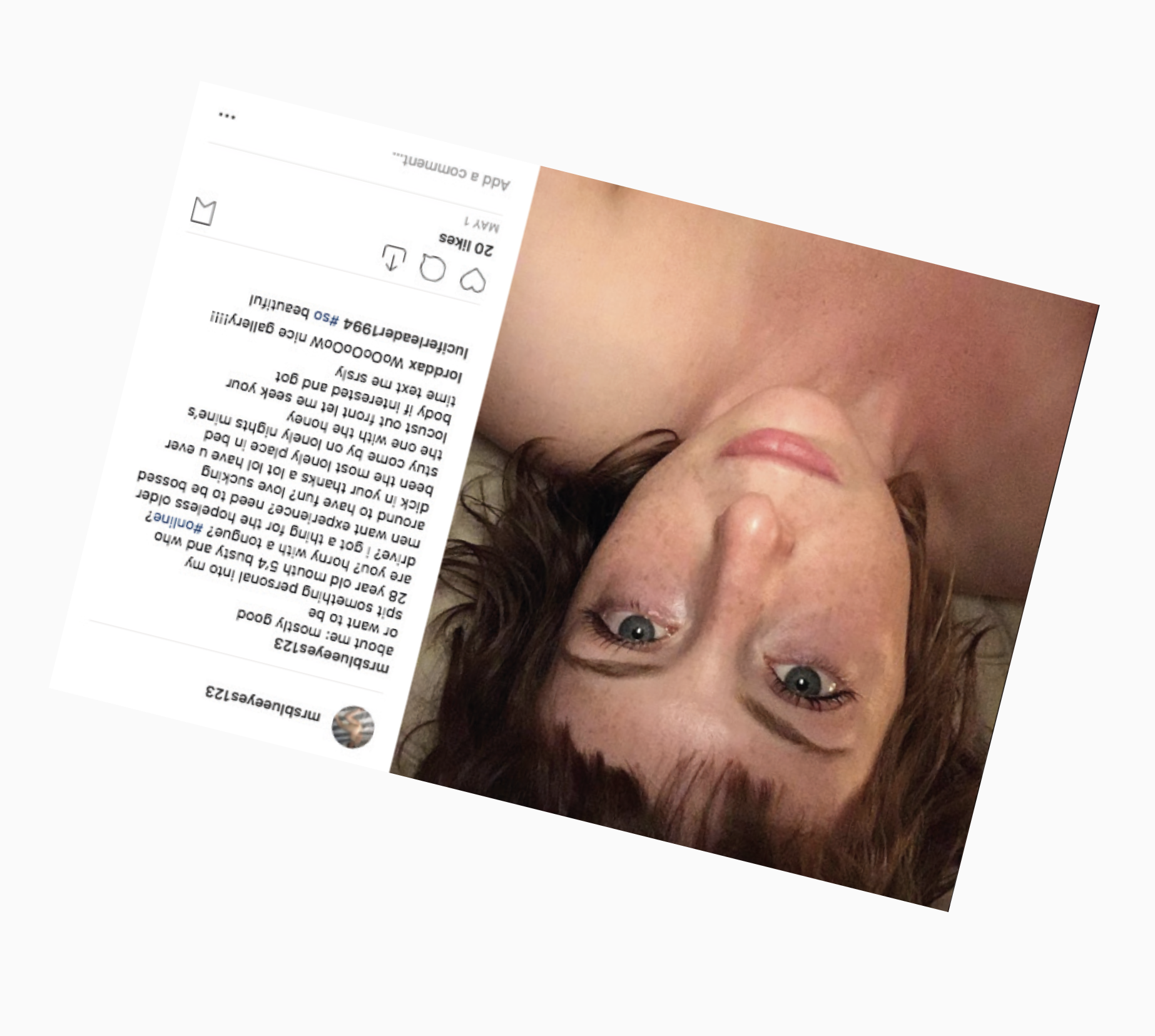

The material in mrsblueeyes123.com was previously published on Instagram between May and January of 2018. The account, @mrsblueeyes123, gained over 2,000 followers in a short period of time. Skolnik’s followers were highly engaged with the work and the artist was known for a responsive relationship with her readers. Some would offer words of encouragement, some gave editorial feedback, and others provided the very language that she appropriated in order to generate new poems for the collection.

But, Skolnik also had readers who took to reporting her posts with such frequency that handfuls of poems were being removed from the page every week, and before long the account was removed by Instagram entirely. As such, mrsblueeyes123 operates not only as a mash-up of Skolnik’s own distinct and discordant desires, but also the desires and projections of people she connected with in varying degrees on the internet. It was a feedback loop which allowed her readers to become intimately and integrally involved in the writing of the collection itself. And, ultimately, in determining its trajectory, a trajectory which resulted in the banning of @mrsblueeyes123 from Instagram and the creation of mrsblueeyes123.com.

Rafael Soldi: Hi Stacy, thanks for chatting with us. Author Sharon Mesmer describes your project, mrsblueeyes123 as being "at the intersections of word and flesh, digital and human." What lead you to create the @mrsblueeyes123 account? What were you hoping to achieve conceptually?

Stacy Skolnik: I didn’t have a master plan when I started the project; I was open to letting the process guide the work. But I had a handful of poems already written that I thought made sense in the frame of Instagram, so I made an account and decided to follow down the rabbit hole. I was drawn to Instagram because of its public nature, and also to the “private” room of the DM, which is where many of the poems in the collection found their language. I wanted to capitalize on the addictive qualities of social media, how much time people spend on their devices/as their avatars looking and reading, to tap into an audience outside of the world of art and literary magazines. I don’t think of myself as a poet’s poet, and I wasn’t wrong to assume that horny guys perusing Instagram might be more drawn to my work and easier to access than, say, the editors at the American Poetry Review or the New Yorker.

RS: For the release event you invited other artists to join you in a series of performances. What went down that evening?

SS: When organizing the launch event for the website, I was drawn to both Abby Lloyd and Vanessa Place because of their own ways of engaging with audience. Abby is a visual artist with a clown-like alter ego named Sassy. At the event, Sassy performed to AC/DC’s “You Shook Me All Night Long” as a bodybuilding strongwoman, guzzled muscle milk, struggled but ultimately triumphed in raising a giant weight over her head, until finally challenging a man from the audience to a gory arm wrestling contest (fake limbs were torn from his body) before dragging and literally kicking him out of the room. The crowd erupted in cheer and laughter at this display of absurd and affected strength (but hey—what’s so funny about a woman being strong?). When the song came to an end and the clapping subsided, writer, performer, and criminal defense attorney Vanessa Place quietly approached the microphone. She read for 10 minutes from her most recent book You Had to be There: Rape Jokes, which deals in its own way with the confusion of comedy. Place refers to her medium as “the situation”, and the power of her work lies in what happens after it passes from speaker to audience. As Place read from Rape Jokes, it wasn’t the writing that was the most interesting aspect of the performance—it was the crowd. You could feel the tension in the room. What were we allowed to laugh at? Were the jokes funny, or were we simply being manipulated by the artfulness of their construction? Does a woman telling these jokes, or being in a gallery and not a comedy club, make it more acceptable?

RS: Why was it important to you to invite women artists who are creating moments of discomfort? It seems like the evening featured topics and activities that specifically make men uncomfortable (women owning their sexuality, women being funny, confronting rape culture).

SS: The only reason men weren’t included in the performance lineup was because none of the men I invited accepted my invitation. Work by artist Corey Presha was featured on the walls, though, and this was a very significant element of the launch. Presha has a particular interest in the distribution of printed matter during the Jim Crow era and appropriates imagery from that time period to create work that is, often all at once, jarring, offensive, humorous, and tender. Many of the paintings feature blackface cartoons in silly situations, though some are from a more romantic or realistic perspective. My favorite of his paintings served as the backdrop for the performances: an intimidatingly huge painting in which we see a man penetrating a woman with his cock at the left of the frame. Behind them is a stretch of open farmland, and even further back the wildness of mountains. Over their heads (and ours) fly planes, those familiar harbingers of war and violence, but also escape. It’s a painting that contains multitudes—the perverted and the lovely, the living and the dead, inner and outer worlds. Such rich complexity is symptomatic of Corey’s tangled relationship to much of the imagery he re-creates, and re-claims, in his work.

At the launch, Presha wasn’t himself present, but the race of the artist was of great concern. I heard several people ask what he “is” and saw visible relief at the response. Presha’s biracial identity meant that these curious viewers were allowed to freely enjoy his art and were spared from accidentally participating in what otherwise would have been a racist event and exhibition. But this left me wondering...what about the race of the gallerist and curator? What about the identity of myself, the organizer of the event? The other guests? In a world of caricature, mask-wearing, social media, how does the construction of our layered identities—socially, sexually, professionally, or otherwise—impact what we can rightly comment on, critique, and engage with publicly? The purpose of the launch wasn’t to answer these questions, but to raise them.

Abby Lloyd as Ms. Sassy at the mrsblueeyes123 launch event

Vanessa Place reading from Rape Jokes at the mrsblueeyes123 launch event

Skolnik reading from mrsblueeyes123 in front of paintings by Corey Presha at the launch event

RS: Though this project exists exclusively on the internet, you think of it explicitly as a book. Can you share more on this choice? Did you find that any of the elements of bookmaking—both process and the way a book exists in the physical world—informed the way we experience the website? How did this format allow you to “undress the creative process” in a way that a traditional book may not?

SS: The quote you use above—“undressing the creative process”—is a phrase from an unpublished review of mrsblueeyes123.com written by my friend and poet Claire Devoogd. So I think it seems appropriate to answer the question using some of her language as well. She writes, "Reading [mrsblueeyes123.com], the pages fall messy and disordered like playing cards one after another across the screen. I find myself lifting and turning my laptop sometimes to peer into the lifted responses of other readers’ avatars. So the book’s container asks that you shift with it. And that you look at things that indict you in a kind of violation. But then it controls you a bit. It refuses to be entirely your thing, you have to interact within the parameters it sets (you can’t dog-ear or note, you can’t flip back, you can’t see everything—were you wanting to?).”

Before and upon its launch I was referring to the website as a book and this was really confusing for people. I’ve since started referring to it as a “collection”, which is also true. But I think of a book as a collection of pages with a beginning and an end and maybe an arc. mrsblueeyes123.com has that, plus some other characteristics that physical books can’t accommodate, such as outlinks, videos, and the opportunity to contact me directly. And I suppose what made the writing of the work on Instagram different than standard book writing processes is that I did it where everyone could watch and participate. The seams are all very visible, which is I think what Claire meant when she said “undressing the creative process.”

Screenshot from mrsblueeyes123

RS: Women's bodies are commodified daily by and for men. Your case here is interesting because of your choice to expose yourself unapologetically and completely on your own terms—that made some people uncomfortable. Interestingly, you were censored because of your words first, and not your images, which says so much about the kind of world we live in.

SS: Well, it wasn’t completely on my own terms. But, ultimately, it was Instagram’s constraints and censorship which added much of the interesting tension and conflict to the work. So I have to thank my haters, lol

RS: What kind of resistance both direct and indirect did you experience while developing this project?

SS: The project is interactive and not reading is really the only way to stay unimplicated in the process, since often times readers' reactions enter the text itself, both as content and constraint, and these actions become part of what the work speaks about and responds to. I think we unfortunately live in a moment where people are as or more concerned with how they “seem” than how or who they actually are. Maybe people were hesitant to engage with the work because they didn’t want to seem a certain type of way. I’m not sure.

Screenshot from mrsblueeyes123

RS: How are you hoping this project can serve you and others moving forward?

SS: That the poems have excited at least a few people physically or mentally is meaningful to me. I also hope mrsblueeyes123 encourages people to interrogate their own relationships to consent and censorship and the erotic, while also calling into question who our gatekeepers are (across platforms) and in what ways they control our desires. And lastly, I hope it might broaden the idea of what a book can be and offer alternative ideas for how publication, distribution, and access can be achieved for writers without money or social capital.

RS: Thanks for sharing, Stacy! Anything upcoming you'd like to share?

SS: Thanks for letting me. And yes—a limited print edition of mrsblueeyes should be coming out with Raw Meat Collective at the beginning of 2020. Stay in touch.

Screenshot from mrsblueeyes123