Q&A: tabitha soren

By Jess T. Dugan | January 23, 2020

Tabitha Soren (b.1967, San Antonio TX) is an artist and Peabody Award-winning journalist, best known for her work as an MTV news correspondent and on-air producer. In 1999, Soren took a fellowship at Stanford University where she shifted her visual arts practice from film to the still photograph. Her photographs are held in many private and public collections, including the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, the New Orleans Museum of Art, the George Eastman Museum of Photography, the Berkeley Art Museum and Pacific Film Archive, the Cleveland Museum of Art, the Oakland Museum of California, and San Francisco’s Pier 24. Soren lives and works in the San Francisco Bay Area.

Jess T. Dugan: Hello Tabitha! Thank you so much for taking the time to speak with me today. I often begin these interviews by asking about an artist’s path to discovering and pursuing photography, but as I was researching your work and life, I learned of your previous career working in television, notably covering politics for MTV as well as covering the presidential campaigns of Bill Clinton and George Bush senior (and winning a Peabody Award for Excellence in Journalism). So, I will still ask the same question, but with that as a background framework: how did you move into fine art photography after your career in television, and what was your path to getting to where you are today?

Tabitha Soren: I come from a military family so I had an itinerant childhood. I was born in San Antonio, TX, but I moved to Sacramento, CA, Tucson, AZ, Homestead, FL, Narragansett, RI, Irmenach, Germany, and Las Vegas, NV all before second grade.

I did take snapshots with my pocket-sized Kodak Ektralite 10 camera while growing up. There is nothing in any of them that screams “future artist”. I used the photos to hold on to memories, really. I took pictures of the house I lived in for 3 years, or of the school I went to for 18 months. I used photography to keep track of the waymarks of growing up. Besides my immediate family, every person in my life changed every three years. I learned over time that if I got pictures of my friends, I could take them with me when I moved.

Additionally, being the new kid in school every few years requires you to ask a lot of questions of the new people around you. Being new in town also helped me develop a way of explaining myself to others, of telling my story while I was introducing myself to each new potential friend. Being good at asking questions and telling a story led me very naturally to a career in journalism after college.

When I began my career in television news in 1989, I shot my own video footage because the station’s reporters were also camerapeople (“One-man bands” was the term used at the time). I continued to shoot my own stories when I began covering politics for MTV News then shifted into directing the camera (aka producing) and being on-camera instead. In 1999, I took up a fellowship at Stanford University where I simply shifted my visual arts practice from 30 frames a second to one frame at a time. I fell in love with photography, art history, and expressing emotional truths in my work instead of exclusively striving for an objective truth (what reporters call the 5 W’s: who-what-when-where-and-why?

JTD: Tell me about your project Surface Tension, for which you photograph iPad screens under raking light with a large-format camera, highlighting the residue of human touch. How did this project come to be? What was your process for working on it? How did you identify your source imagery?

TS: My family life had a lot to do with beginning Surface Tension. I seem to always be arguing with my kids about how much daily screen-time they have. I also spend a lot of time juggling a zillion windows and applications on my own studio computer and on my phone. I find that all of these situations get my head spinning, my brain distracted, and my temperament becomes impatient. It’s just not a good psychological state to be in and I knew so many people who complained of the same cognitive impairment. That encouraged me to try to make art out of it instead. Honestly, shooting Surface Tension was a way to vent about technology at first.

I originally made black and white negatives but decided pretty quickly that they looked a bit too imitative of painter Franz Kline’s work. So, I switched to color and that’s when the fireworks went off. I had never seen any photographs like them. That’s when I know I have an idea worth pursuing. I get discouraged sometimes because there are days when it seems like every picture has been taken. Instead, the contact sheets I got back from my first Surface Tension color shoot on the 8”x10” camera made me want to skip back to my studio and get right back to taking more.

JTD: To make these images, you used an 8”x10” large-format view camera and film, a slow process that is in opposition to the quickly viewed and consumed images you’re photographing. Why this media and method? What did it provide to both you as an artist and to the work itself?

TS: I really wanted to s-l-o-w down the process as an antidote to the rest of my life. Plus, I knew from the get go that these pieces needed a large scale to separate them from the quotidian scale of an actual real life tech device. An 8”x10” negative gave me a lot of flexibility about size without giving up sharpness. By shooting and printing the photographs this way, the viewer is forced to see an everyday object in a way they usually don’t.

What I also found when I eventually made the work mural size is that you could see more of the conflict between technology and humanity that way. The sweat, fingerprints, debris and dirt were all a lot easier to confront at the 6 x 8 foot size. Our devices are designed to be oil resistant and perfectly smooth. Slick digital culture can tell us that there is something physically inferior about us – our oils, hair, saliva – but I disagree. On one level, this project is an attempt to remind us that our humanity is beautiful. The large negative really allows that idea to be more apparent. Our devices are swirling with the messy fingerprints and greasy smears of our embodied selves. Human beings are all so naturally at odds with the chilly detachment and objectivity of the information that flows towards us, unrelentingly. There is an inherent tension there and it must affect our mental states somehow.

The messiness of life, the unpredictability of it, is central to the process of making art for me. Working with film allows for plenty of happy accidents (and yes, there are unhappy ones, too). The act of photographing is a response to how I attempt to consciously manage the uncontrollable possibilities that exist in life. When I’m shooting, I’m not just accepting of imperfection. I’m looking for it. For example, in the Fck Yeah image, the hot spot, instead of being a mistake, is actually what makes this photograph so dynamic.

In my mind, the glow from the analogue negative (instead of a digital sensor) also makes the prints much more spiritual. For me, they connect to art history in a meaningful way because of this. Historically, we as human beings are in this fundamental battle to transcend the physical. If we circle way back in art history to stone age cave paintings, those artists or their entourages left hand prints in caves.

They were palping a living rock perhaps with hopes of reaching or summoning a force beyond it. Just like we are doing with our screens now. Which is to say that when we engage as we do with our screens we forge a link between the ancient and the modern. When we press and push upon our devices we enter another, older world. I consider the fingerprints on our devices to be our contemporary cave paintings.

JTD: Writing about this series, you say, “touch is a language in and of itself, essential to what it means to be human.” You also write that Surface Tension “exposes how much our humanity is in direct conflict with the daily fight against technological domination.” We are living in a time when, theoretically, connection is at its highest, thanks to technology and social media. Yet, it seems to me, we are moving away from real, meaningful, complex interactions, which have been replaced by superficial, truncated communication. I assume you were thinking of all of this while making this work, but can you expand upon these ideas and share your thoughts about both touch and connection?

TS: Scientists are studying how our interaction with these devices affects the way we treat each other. One result is a condition called “digital narcissism.” That’s what the three plexiglass Narcissus floor pieces in the exhibition relate to. They are made to reflect viewers back at themselves when they stare down into them. They are inspired, of course, by the Greek mythological figure Narcissus, who fell in love with his own reflection, and, unable to move away from it, died as a result. Staring into our devices is not unlike Narcissus and his reflection.

It won’t surprise your readers that recent studies have shown that social media websites that encourage self-promotion, branding oneself to get attention and generating the perfect selfie increases narcissistic personality traits. Just to be clear, narcissism is thinking only about yourself, exploiting others, feeling entitled, and having grandiose exhibitionism. Heavy Facebook users, for example, are more likely to negatively compare themselves and feel worse about themselves. Daily Instagram users report feeling inadequate because of the tension between a selfie’s presentation of perfection and the precariousness of sense of self underneath. Interestingly, the study showed that those who primarily engaged in social media for verbal posting, such as Twitter, did NOT show these tendencies (39,000 college students, over 4 months average increase of traits was 25%).

Numerous other studies show that traits of narcissism correlate with everything from compulsive social media updates, checking numbers of followers, frequency of selfie posting and the motivation to use social networking sites to appear “cooler” to others – and that’s just one of the reasons why anxiety has overtaken depression as the most common reason that college students seek counseling services. Science tells us that living with such a narrow view of reality – me, myself and I – focuses people on who they are on the surface, the superficial layer of life, which decreases community and consequently, happiness.

At this moment in contemporary culture, technology is being used to accent our differences, as a way to divide us. I hope that one element of Surface Tension is skepticism about technology but another hope is that it foregrounds solidarity: accenting the way we are similar in a unifying way. For example, our skin all responds to touch in the same physical way.

A pat on the back, a caress of the arm – these are everyday, incidental gestures that we usually take for granted, but they are far more profound than we realize. They are our primary language of compassion, and a primary means for spreading compassion. Touch is first processed by the skin, an organ made up of billions of cells, which sends neurochemical signals to a large region of the cortex – the somatosensory cortex – which brings to consciousness the precise nature of each tactile contact with the outer world, whether it is friend or foe, potential lover or letch, toxin or harmless element. The fingertips and tongue are much more sensitive than the back. The hairiest parts of the body are generally the most sensitive to pressure, because there are many sense receptors at the base of each hair. Touch is the oldest sense and the most urgent. If a saber tooth tiger is touching your shoulder you need to know. But instead of touching each other, we are touching our devices.

Evidence of society’s collective internet habits – and the underlying desires that shape them – can be boiled down to the giant Surface Tension collage of porn and cats. At first cats and porn may seem like a funny pairing. However, the two subjects that Americans spend the most time with online are porn and cats: a simulated sexual experience and pets who belong to someone else. Human contact is fraught these days. It’s possible that all this porn and cat watching leads those engaged in it to find meaning and satisfaction in their lives. It’s also possible that people are confused about how to find meaning and satisfaction. These images explore a tension, between the real and the virtual, and the trouble people have distinguishing between the two. Tech allows us to replace the most intimate act and devoted relationships with virtual imitations.

People are spending more time using social media, playing video games and, yes, watching pornography, instead of interacting with each other in the real world. Even the amount of sex Americans are having has gone down. In a cover story for The Atlantic last year Kate Julian pointed to a 2017 Journal of Population Economics study, which found that the introduction of broadband internet explained 7 to 13 percent of the decline in the births to teenage mothers between 1999 and 2007. “Signs are gathering that the delay in teen sex may have been the first indication of a broader withdrawal from physical intimacy that extends well into adulthood,” she wrote.

Some more examples:

There are 1.6 billion swipes per day on Tinder alone – so we obviously feel the need for some sort of connection. But how many of these swipes lead to that?

In Japan, there are Zentai tights which is a head to toe body suits that are so tight you have to have help to get into it. The point is to feel an embrace all day without having to depend on someone else to give it to you.

Other marketers are offering self-care as a stand in for intimacy too: the Hygge blankets, sex doll brothels, and you can even hire a professional cuddler. “Cuddle Up to Me” and “Rent a Friend” are both real companies. They are about touch and companionship – but not sex.

JTD: Some of the images in Surface Tension are overtly political, depicting moments of police brutality and the climate crisis, while others are more personal, such as vacation photos or an e-mailed picture of a goodnight kiss from your daughter. How do you think about the interaction between the personal and the political, particularly when thinking about how many of us access nearly everything, as you mention, through technology?

TS: The personal images all relate to the sense of touch – and touch in a rewarding, positive way. A recent study at Cal Berkeley, published in the journal Emotion, found that in general, NBA basketball teams whose players touch each other more win more games. Warm, friendly patterns of touch calm down the recipient's neurophysiology of stress. In one study, simply holding the hand of a loved one deactivated stress-related regions of the brain when anticipating going through a stressful experience.

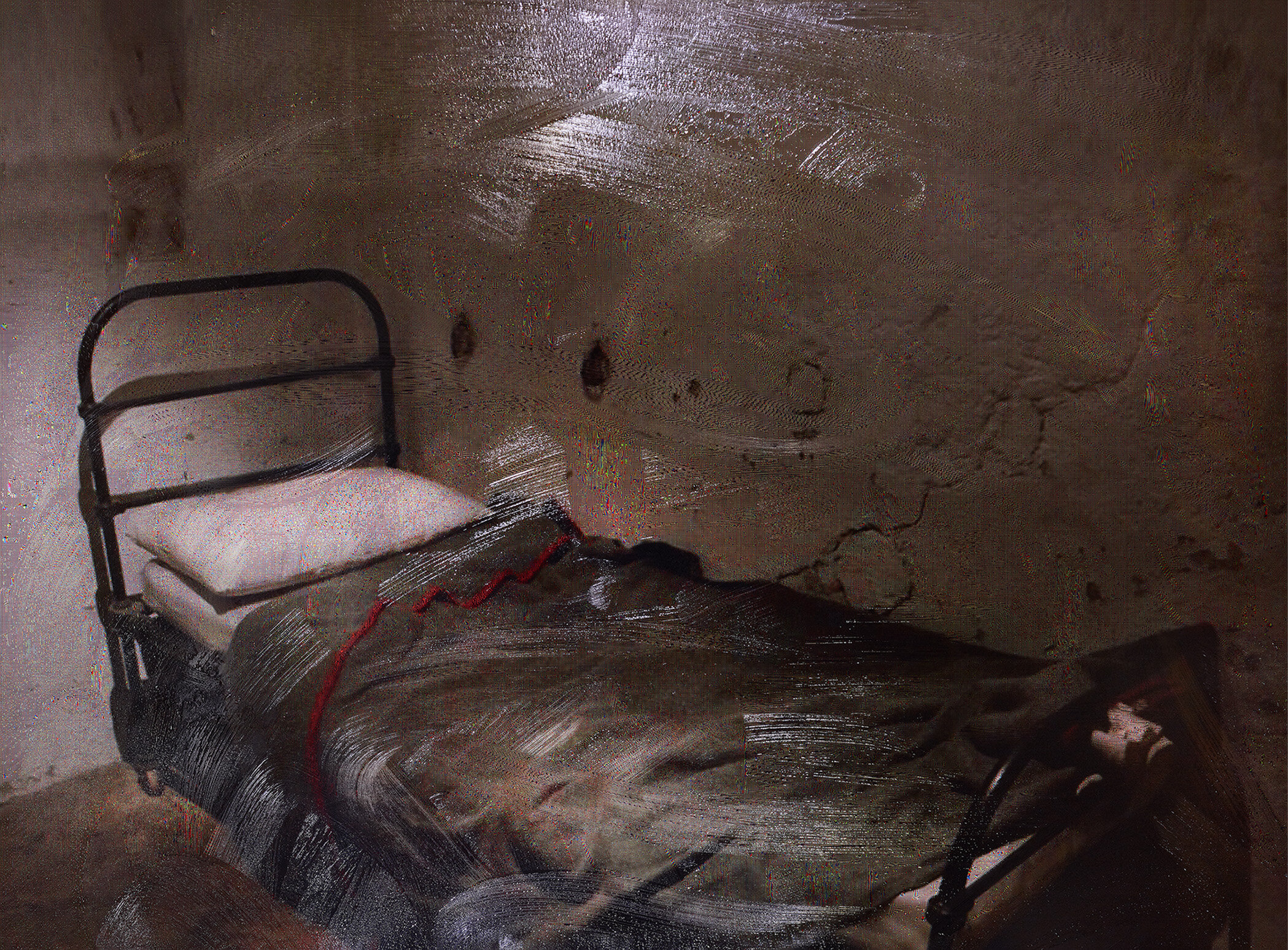

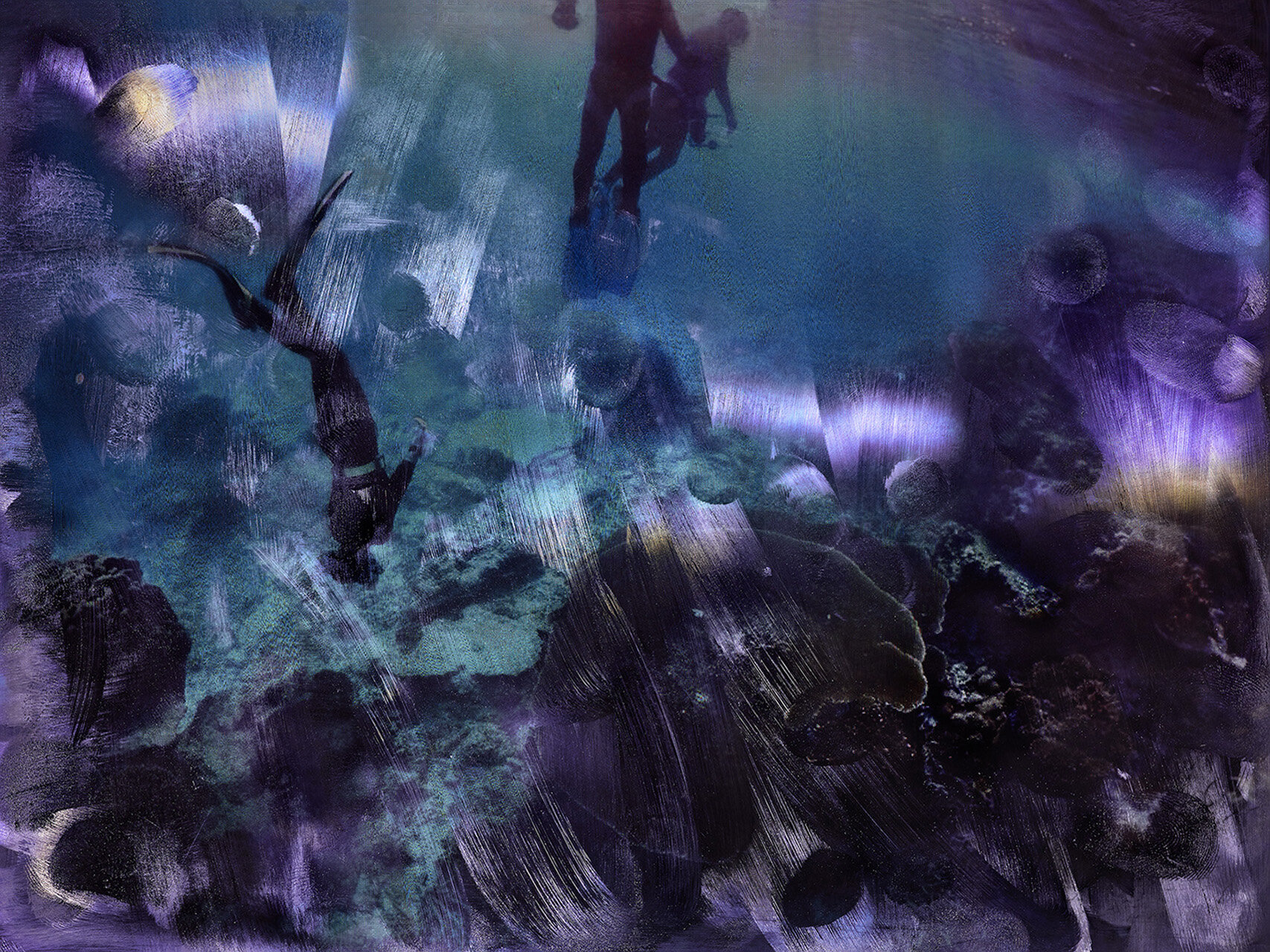

In our public discourse, though, nothing is what it seems. We live in a political moment where it seems reason has gone out the door. The dreamy blue scene in Surface Tension looks like a painterly landscape – and it is. But it is also a civil rights photograph made from a Ferguson, Missouri protest in 2014. The image is about the fatal harm done to Michael Brown through the brutal touch of Ferguson police officers.

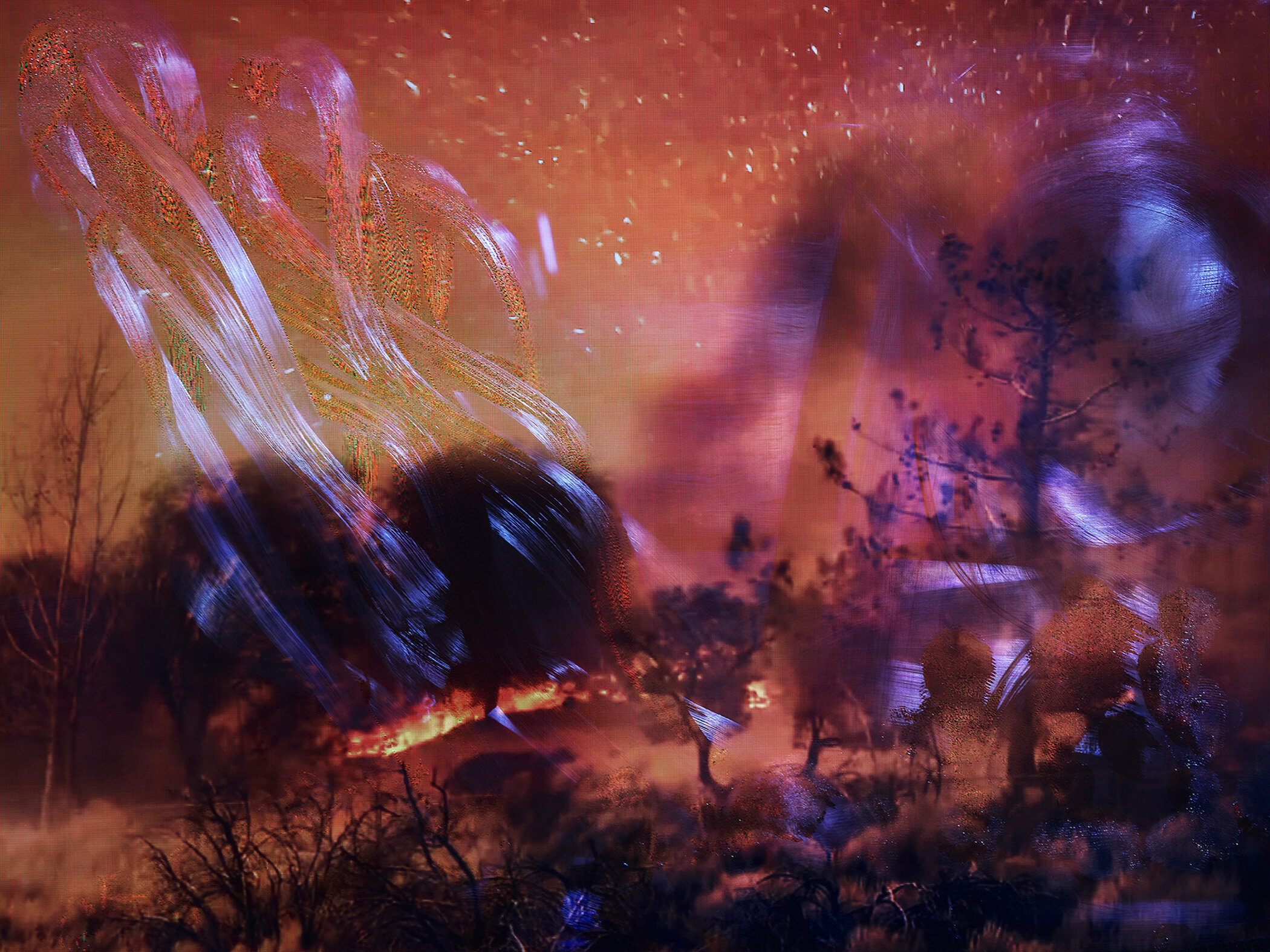

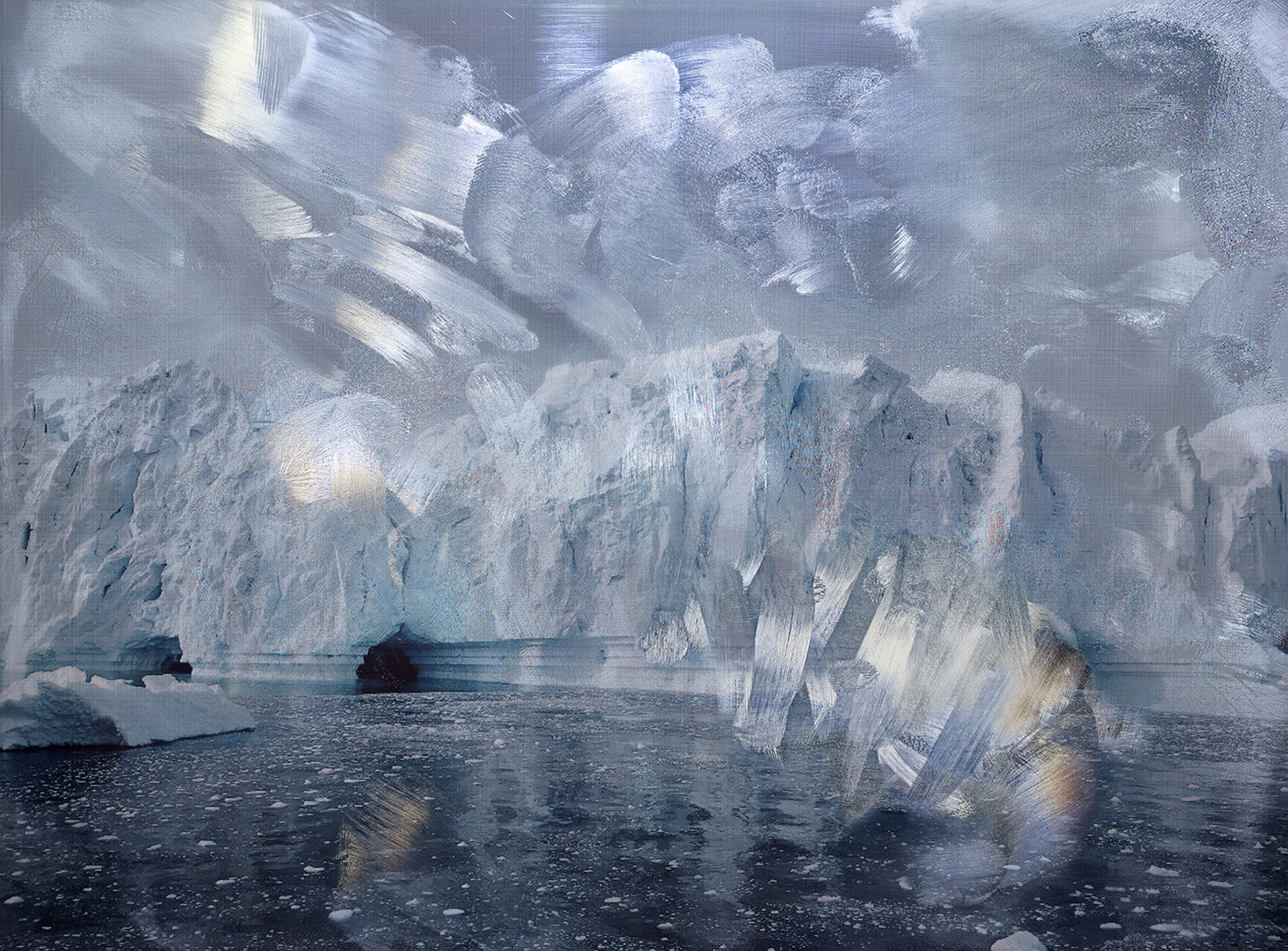

Harmful touch is the other side of the coin, and so about half the images in the project are devoted to that. The photograph of Greenland is about the fact that it is shrinking due to humans shaping the surface of the land. Greenland is only one example of the way human touch causes damage to the very beauty we are in search of by visiting places like the Arctic, Venice, the Great Barrier Reef... etc. Many of the pictures about harmful touch in Surface Tension are about the need to change the racial narrative in our heads. The Kalief Browder and Tamir Rice photographs are there because the story that labels children – mostly black and brown boys – as “super-predators” leads to unjust sentences and horrific outcomes. Technology and social media didn’t create this false narrative but they have the ability to spread misinformation faster than ever before.

Let me give you another example of technology leading to harmful touch: artificial intelligence’s predictive policing is an analytical technique used by authorities to identify locations of potential crime. It has been widely criticized by social justice organizations for its reaffirmation of racial profiling. Technology allows machine eyes to be omnipresent. They scan social media profiles and security databases. They watch us watch tv and follow us around shopping malls, trying to glean information about what products we might be interested in buying. They monitor our movements in airports and parking garages and register our license plates as we pass a traffic light. It leads to people being mislabeled. It leads to police officers shooting a child two seconds after arriving at the scene. Or an aunt being killed inside her own living room while playing video games with her nephew.

JTD: It seems that we’re experiencing a moment where many people are starting to critique this influence of technology on our lives and culture, or at the very least, recognize the downsides you mention in addition to the well-promoted and highly-marketed advantages. What are your thoughts about where we are, as a culture, in relation to technology in this moment? Do you feel that there may be a move away from technology, or do you feel that our addiction to it will only intensify?

TS: I do think people are starting to recognize the attention economy. But addiction, or even a plain old habits, is hard to break. I can tell you that I took all social media off my phone and I’m still on Instagram all the time. It’s embarrassing. As everyone is aware by now, fake video and audio are increasingly difficult to distinguish from actual news footage. The information that shapes politics and war alike is created by clever humans using viral engineering. The wars of tomorrow will soon be fought by highly intelligent inscrutable algorithms that will speak convincingly of things that never happened, producing proof that doesn't really exist.

I also think (hope) that we are all getting smarter about this and that will lead to relying on technology less. I want what Alexander Nix of Cambridge Analytica said to stick in people’s brains when they’re analyzing current events. He said, “things don't need to be true as long as they’re believed.” This is undoubtedly how we ended up with a President who thinks he’s entitled to his own set of facts.

JTD: Your exhibition Surface Tension debuted at the Davis Museum at Wellesley College in Wellesley, MA earlier this year, was recently on view at the Transformer Station in Cleveland, OH, and is headed to the Mills College Art Museum in Oakland, CA in the fall of 2020. What has your experience been exhibiting this work? Have you received any particularly interesting or notable feedback? Do you have plans to make a book of this series, or do you view the exhibition as the primary final form?

TS: I have expanded and customized each of the exhibitions in an effort to reflect the community and time period in which the work is being shown. For example, the upcoming Mills Museum show will feature many more Americans resisting the parts of our culture that don’t reflect their values because it will overlap with the 2020 US presidential election. There is more protest and anger in the Mills show than the original Davis Museum exhibit. Also, the Mills curator Stephanie Hanor and I are working on a Narcissus immersion room which will be a meditative antidote to the bright palette and frenetic tension of the exhibition photographs outside in the large gallery. Nothing is set in stone yet, but it’s been a real learning experience to be able to keep digging deeper into the work. Last year, I also really loved working with curator Lisa Fischman at The Davis Museum who helped me edit a three year shooting extravaganza into a really tight initial exhibition so that the work was about more than appropriated pictures from my internet history.

And yes, I would love to publish a comprehensive Surface Tension book. I am a total photobook nerd and collector. I do have a concept for the book but I need to decide which publisher can afford my ideas. I loved working with Lesley Martin at Aperture for my first book, Fantasy Life. Books take a lot of time, though, and right now, the shows are dominating my schedule. I like to dwell on every aspect of making a book – even the color of the headband.

JTD: You have said that you prefer to work on multiple projects simultaneously- what are you currently working on, and what’s on the horizon for you as an artist?

TS: I’m working on turning photographs into reliefs. I’m tired of my work being flat. The new work is a mission to photograph the unseen political geography of our times. It looks at the way humans shape the surface of the earth and how that in turn, shapes us. The photographs themselves take on new shapes and become reliefs, through rips, slices and carvings in the paper. It’s slow going. I only have about 12 images that I like so far.

I also have a project called Uprooted that arises, in part, from my wonder at what human beings survive – and what they don’t. This work began in 2005, when The New York Times Magazine sent me to photograph the aftermath of Hurricane Katrina. I’ve been revisiting the same 14 Orleans Parish lots twice a year ever since. I’m attempting to tell the story of the tension between the old and the new, the particular and the diverse, the efficient and the delightful, through the spaces in which people choose to rebuild or in some cases, choose not to. Uprooted is a way for me – and an invitation for the viewer - to dive into the unpredictability and complexity of life. It’s not as if we have much choice about the havoc anyway. This work acts as a metaphor for resilience. One doesn’t have to live in New Orleans to know what it’s like to pick one’s self up again and start over. I’m wading through 15 years of diptychs – mostly shot on film. So again, slow going.

JTD: Great, thank you so much Tabitha- I’m looking forward to seeing the new work!

All images © Tabitha Soren