Q&A: Tomiko Jones

March 28, 2019

By Hamidah Glasgow

Loose narratives unfold in sculptural video installations and questionably fictional photographs. Tomiko Jones' work is linked to place, exploring transitions in the landscape in social, cultural and geographical terms. Jones received her Master of Fine Arts in Photography with a Certificate in Museum Studies from the University of Arizona in Tucson.

She is the recipient of awards including the 2013 En Foco New Works Fellowship (New York), 4Culture and CityArtists (Seattle), and Pépinières Européennes pour Jeunes Artistes (France). Recent projects include Hatsubon, a two volume project in photography and video installation; the long-term project Rattlesnake Lake; and the immersive theatre performance The Gretel Project, a four-person collaboration. Tomiko spent three months in residence at Museé Niépce in Chalon-Sur-Saône, France, and in Cassis, France for a project-specific Fellowship at The Camargo Foundation.

Currently Jones is an Assistant Professor of Art at University of Wisconsin-Madison. As an educator she was a Visiting Artist and Curator-in-Residence at California Institute of Integral Studies in San Francisco, Assistant Professor and Photography Program Coordinator at Metropolitan State University of Denver, Mendocino College, New Mexico State University and Drury University Summer Institute for Visual Arts.

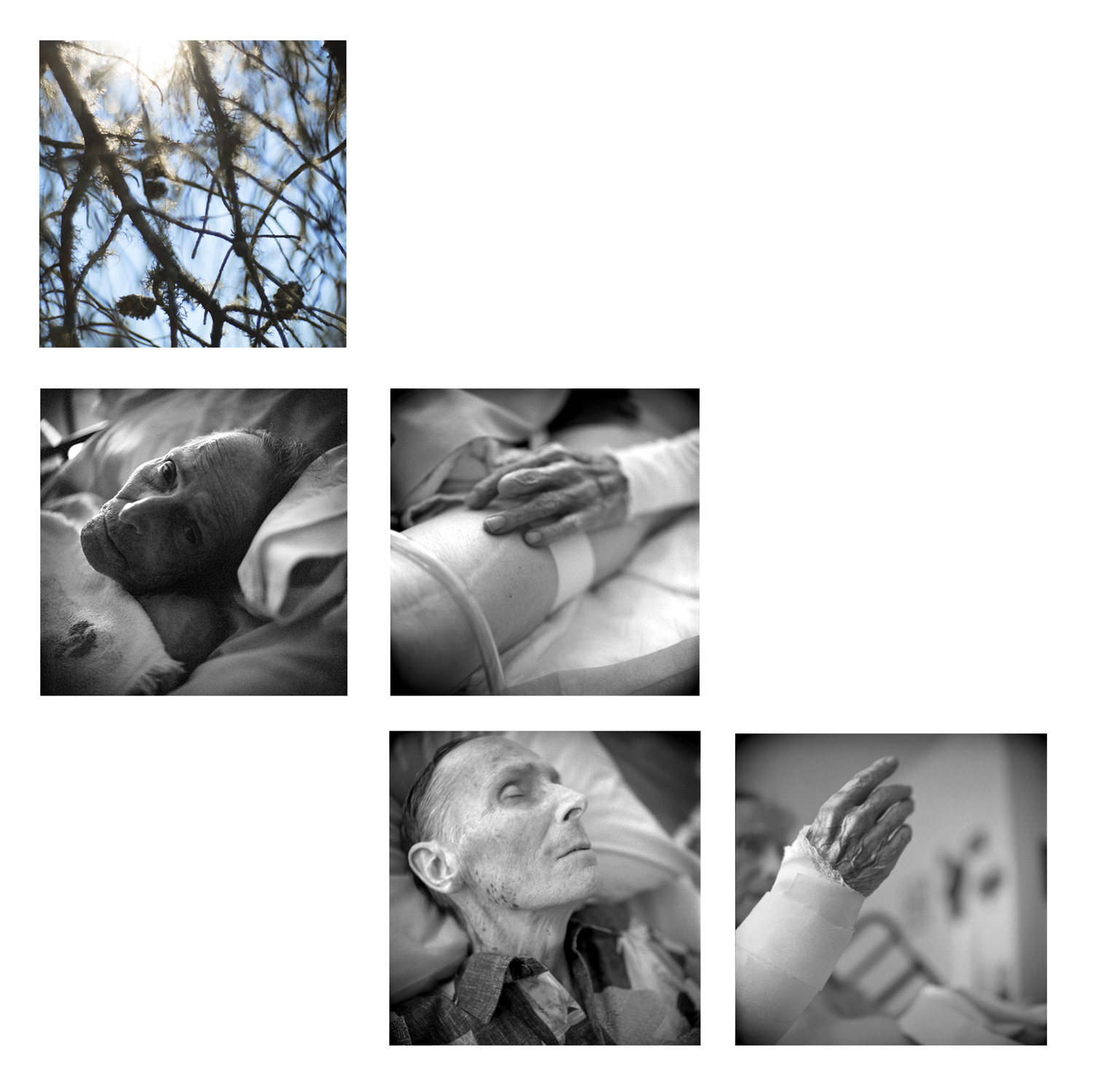

Hatsubon is a memorial exhibition exploring the dynamic tension between tradition and performance through photographs and video, and include portraits of my father in the diaphanous space between life and death. The materiality of the exhibition suggests repeating dualities from the fleeting and the lasting– with floating silk landscapes and solid walnut framed images of the body and its urn, to the ephemeral and the corporeal–with suspended ribs of the skeleton boat and the heft of the hand-carved wooden oar. Relationships between and amongst object, place, and landscape come together in a pendulous state of longing and release.

Hamidah Glasgow: It’s been fascinating to see how Hatsubon has evolved. Tell me about that evolution and the factors that have affected the work?

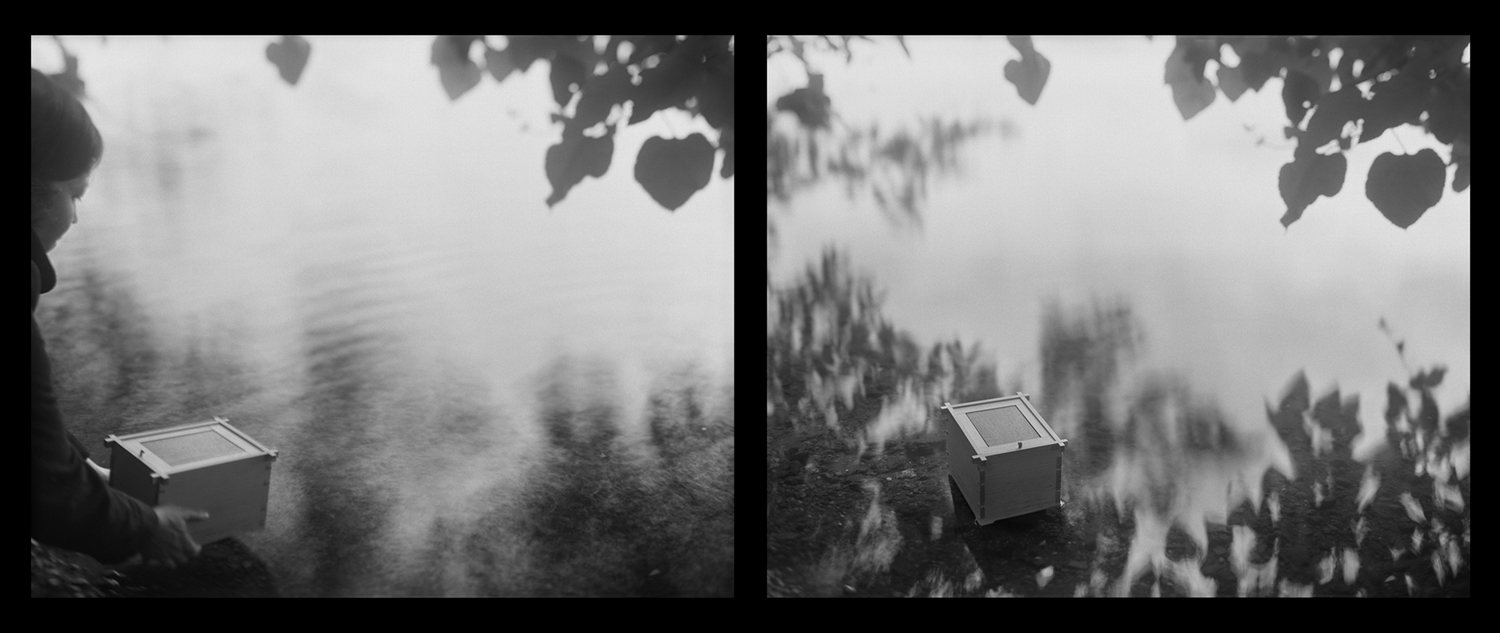

Tomiko Jones: Thank you for these questions. I’ve heard myself the say; the work made itself. My mother and sister and I had cared for my father in the last months of his life in home hospice care. Immediately following his passing in July 2016, I started a residency in San Francisco. I was working on a project on the regional watershed and the twin crises of drought and sea level rise. I made many images, but every time I was near water, I started by folding a paper boat for my father and sending it off, a ritual for the loss I was feeling. It wasn’t until May that I met with Deirdre Visser, curator, and through our conversation, I accepted I was making work about grief, not ecology. In July, we were going to Hawai’i for O-bon, a Japanese Buddhist ceremony honoring ancestors. It was my father’s Hatsubon or first year anniversary. I asked my mother and sister to perform a traditional ritual of setting a boat to sea and asking if I could photograph it. It all happened very quickly, with the exhibition opening in September (2016, Desai | Matta Gallery, California Institute of Integral Studies, San Francisco).

All things shift with time. I have grown and changed with Hatsubon. With each opportunity to exhibit the work, I add another layer in an expression of grief, loss, sorrow and my relationship to death.

The video installation of Hatsubon came while preparing for Kipp Gallery (Indiana University of Pennsylvania, November 2016). When I went for the site visit, the curator, Chris McGinnis, was happy to accommodate my idea for the reflecting pools and committed to building them for me. I had previously installed outdoor projects with moon-shaped projection scrims reflected on water (“La Traversée” 2008, “There Are Some Things You Can Not Forget,” 2009, “Canal” 2012). I sought to bring this contemplative image to a gallery interior. Throughout the summer I had captured footage of water at three sites: Pennsylvania, my father’s birthplace, Hawai’i, my mother’s birthplace and where he is buried, and California, where my parents met and my birthplace. These three places are present throughout the photographs and video in “Hatsubon.” I had just under two months between exhibitions, just enough time to make the skeleton boat.

In September 2018, I installed the work at Phebe Conley Gallery, California State University, Fresno, CA. The gallery was much larger than any I had been in yet. Many images had been edited out in the initial process; I returned to them and kept pausing on the one of my mother, sister and I holding the boat on the shore before stepping into the surf. It was ruined by a light leak streaming across the film, but I wanted to include it. Several summers ago, I had cast over a hundred porcelain boats; I placed them on shelves to create a line of movement between the images. There was an entire darkened room for video and was able to spread out the pools and projection scrims more spaciously.

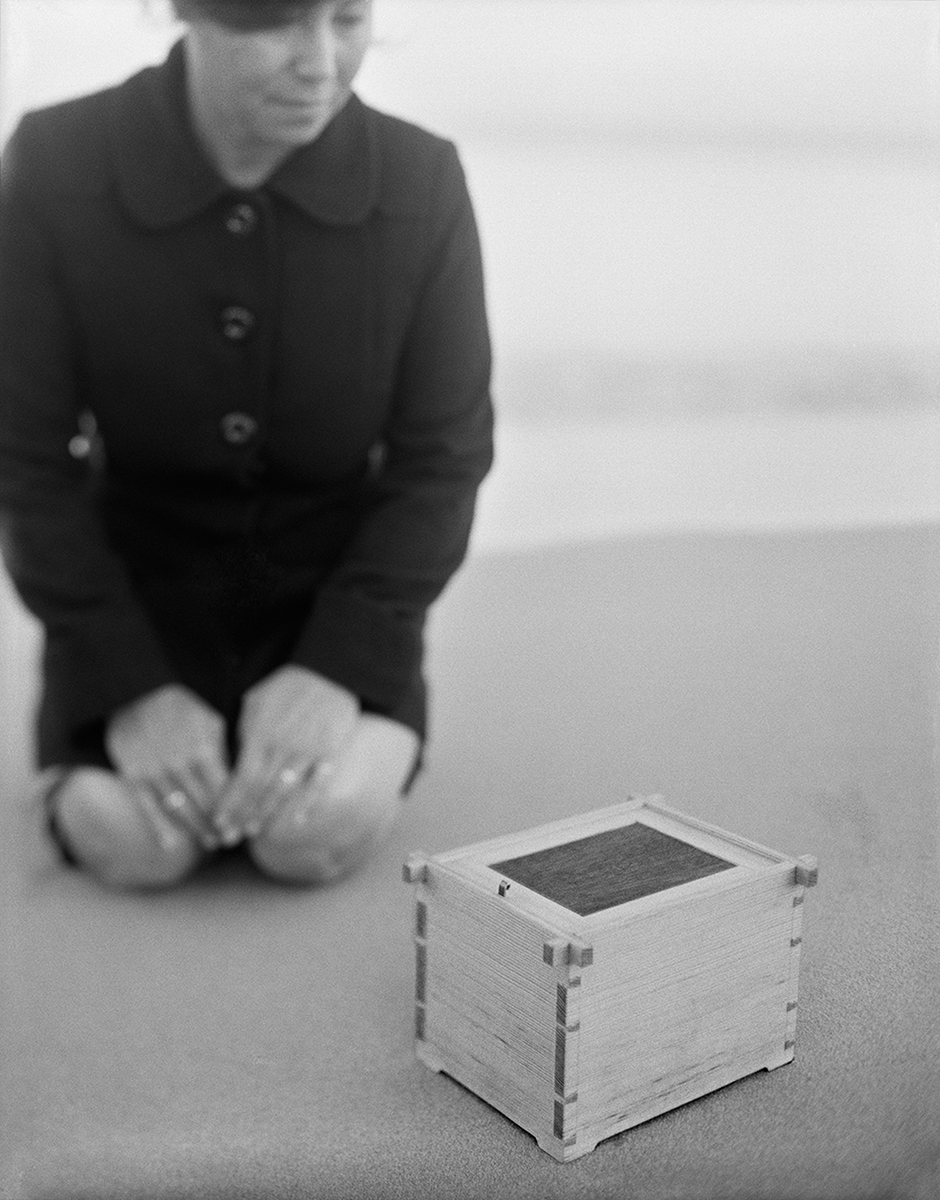

The latest evolution was at Northlight Gallery, Arizona State University, in January 2019. I was dreaming of making a tiny urn, a version of the one where his ashes remain interred, as a symbolic sculpture. There was a single piece of Douglas Fir leftover from the original urn, just enough to for this one. After months of learning fine woodworking techniques, I was able to complete it. I refined the Skeleton Boat with bridal joints of leftover cherry wood from the oar. I made new shelves of walnut to hold the porcelain boats. There was a whole room for video, but this time I let go of the scrims and projected straight onto the walls. This show felt so complete.

HG: Your work continues to include video and sculptural pieces. How do these non-photo elements become part of your Oeuvre?

TJ: I’m primarily identified as a photographer, but I more often think of myself as an artist. In a way, everything is an image; it’s just a matter of what medium we use to make it. There are times when the image wants movement, a suggestion of time or motion through space. I often use slow shutter speeds in a photograph, but often this is where video comes in. Most of my videos are not narrative, but are atmospheric, meant to illustrate a place, a feeling, of “here.” I’ve always loved working with my hands, and so the process by which I arrive at something is important, whether it is the material or the tools. Sculptural pieces again are images. In Hatsubon, “The Oar” came from an end of life conversation with my father He called out in the middle of the night “bring me the oar” to help him arrive at the other shore. I could not forget this moment and knew I needed to make one for him. This could not be a photograph; it needed to be an actual object. The act of carving away, a reductive process, was cathartic; learning to move with the grain of the wood and shape it slowly and with tenderness. I only ever used a blade and directional movement. I remember a woodworker friend saying that sandpaper was violent, it moved any which way, against the flow of the wood, without regard to its growth and life. To make such an object, I knew I should move with it. Intuitively, I knew it should be made with cherry.

Exceprt from A Letter to My Father:

People don’t want to die. It is hard to be there when someone you love is dying, but I would not dream of being anywhere else. I remember it was only a few days before your last one with us, although we could not have known it then…

We were together, you in the bed thinking and me on a chair dozing. You asked me, what are we going to do with all of our things? I asked, these things? Indicating the objects in the room. You said, yes, if we are leaving, what should we do with all of our things? I said I don’t think we need to do anything; we can leave them right here, we aren’t going to be needing them. Then you asked me, how are we going to get there?

I will never forget this moment, trying to imagine what you were seeing when you said there. I knew you were talking about a place outside of this visible world, someplace on the other side of the thin veil that separates us from the rest of the unseen and unknown world. How are we going to get there? I asked. Yes, you answered(…) I guess we can travel however we want, I said. I began to list the more usual ways of travel (…) You looked at me and asked, how would you go? I just smiled and said, you know me, dad; I love boats. I would go by boat! You smiled back and said, that sounds good.

You eventually fell asleep, and I settled down on the couch for the night. Bring me the oar! you called out. I woke suddenly, leaping from the couch. Your eyes were open, and you were looking upwards. I came to the bedside. You were looking right at me, but I was not sure if you were really seeing me. I knew what you were asking for. I laid my hand on your arm and your eyes closed, and you returned to sleep, or to whatever world you already had one foot in.

I have thought every day of this since you’ve been gone, of you calling out, bring me the oar! I think about how I should make you one. And how I would like to make you a boat, too.

The skeleton boat was a similar process. I wanted to make it out of a single log, in the Shinto animism of the tree. I thought if it as representing the body. I searched all summer for a log large enough.

At first, I sought out a western red cedar because I love them so much, and so did my father, and we had lived a significant portion of our lives in the northwest. I was living in California, and so I began to look for a redwood, which is a magnificent tree, and I was living in the land of redwoods. I had heard that during the early devastating logging days, sometimes a tree would be lost to the ocean. In time, these logs would be seen by boats and recovered or even make landfall on their own. I loved this metaphor. I searched for a salvage log but was unable to one after months, and I had the second exhibition deadline, so I began to think of other ways I could make the boat to fit his body. I came to the idea of the skeleton form. I have made this form many, many times over the years, just never this big. I came to ash as the tree of life in the Gaelic tradition (honoring the Jones). Once I started to form the boat with steam bent lengths of ash, I saw the body come to life. I had made cross-braces and the other components, but once the ribs were in place, I knew it was finished, and stopped. It sought to be simple. In this way, I do plan, but I let the materials guide me.

There are other forms in my work, like the reflecting pools, porcelain boats, moon-shaped scrims. The moon came early on in my photographic practice, before photoshop, when I would tape a toilet paper tube to the end of my Rollei to create a circular vignette. In 2005, when I began to work in video, I started projecting in a circle or building circular objects to project onto. (My MFA thesis included two circular projections.) These all are significant and recurring motifs. In earlier days, I made sculptures to be part of my photographs, but in more recent years, the sculptures wanted to be on their own and held in space.

HG: How would you describe your artistic practice? Do you pre-visualize the work or do you work more intuitively?

TJ: My practice almost always engages the landscape-it is instinctual, familial, cultural, memorial. I feel it is nearly always a reflection of the lived experience. An essential aspect is the serendipitous, or relational. Conversations and dreams influence where I go, how I see, and what I make. There is allegory. Proverb. Stories, both mine and others in relation to my own. A single thing someone says to me can spark an entire body of work.

There are times I have a very clear idea of what I think something should look like. In those cases, I storyboard, and I scout. For Hatsubon, during the ritual of setting the boat to sea with my mother and sister, I needed to plan. We sewed our yukatta; I made the boat out of steam bent bamboo, waxed Kozo paper and a banana leaf from my grandmother’s yard. Once we were in Hawai’i, I found the place near my grandmother’s house; I looked at the sunrise table and the angle of light; I sketched out the storyboard, knowing we had a short window of time before sunrise and my cousin was helping on camera and needed direction. In this case, I pre-visualized.

In thinking of Ansel Adam’s “pre-visualization,” I suppose I do that, too. Once I find “it,” I make technical decisions to try and best capture what I see in my mind’s eye. Talking about this is interesting. It could also be said it is a reason I mostly work alone, and when there is a figure, it is my own. I do not need to direct myself. When I step into the image, I know what I need to do or where I need to be. Not that I always get it right!

I studied Cultural Anthropology with a focus on religion, myth, the divine, and imagery that emerged from it. I always wanted to understand how people lived, how and why, around the world. I trained to think this way, but over time, I began to sense I could only really tell my own story. Everything is interrelated, and so I feel others come into the work. I am influenced and concerned about the state of the planet, and in my research, I draw on natural history, social, cultural and political history. Though my work is not documentary, this research figures into my practice.

I sometimes set parameters, but mostly I don’t worry too much. I begin the walk and let myself be lead. This giving up of oneself to the creative, to the practice, has been the most profound thing in my life. I am continually amazed and grateful for it. Making is an act of love.

HG: What are you up to now and in the near future?

TJ: I remember a friend and mentor said something to me; I had never forgotten when I was in the middle of working on my first in-depth series, “The Bunny Chronicles.” I had not gone to art school, so was lacking in the formal study of concept, process, and critique. I was working in a commercial photography lab with creative co-workers. One night printing after hours, I asked him to look at the prints. He said, don’t talk too much about it, it will take the magic away. Stay with the work, and you’ll know what to do. I think about this a lot. But, we all need feedback, and we need to bounce ideas around, and I live in a world of proposals and grant writing. So, all that said! I am working concurrently on several things, many of which feel like lifetime projects. There is the continuation of “Passage” (shown in 2010, started in 1989), which is about the migratory passage of my family and generational knowledge, there is “These Grand Places”, a relational public land project that requires me to spend much more time in the field, and of this current geo-political-environmental moment in history. Since my collaboration with Jonathan Marquis in 2017, I’ve made hundreds of cyanotypes on-site, they are abstractions of the sun, water and time. I continue to photograph every bed I’ve slept in since a few months after receiving my MFA, “A Place to Rest” (2009-ongoing).

HG: Thank you.