Q&A: zinnia naqvi

By Lodoe Laura | September 19, 2019

Zinnia Naqvi is a visual artist based in Tkaronto/Toronto and Tiohtià:ke/Montreal. Her work uses a combination of photography, video, writings, archival footage and installation. Naqvi’s practice questions the relationship between authenticity and narrative, while dealing with larger themes of colonialism, cultural translation, language, and gender. Her projects often invite the viewer to question her process and working methods. Naqvi’s works have been shown across Canada and internationally. She received an honorable mention at the 2017 Karachi Biennale in Pakistan and was an Artist in Residence at the Art Gallery of Ontario as part of EMILIA-AMALIA Working Group. She is a recipient of the 2019 New Generation Award organized by the Canadian Photography Institute of the National Gallery of Canada in partnership with Scotiabank. She has a BFA in Photography Studies from Ryerson University and is currently an MFA Candidate in Studio Arts at Concordia University.

The Wanderers - Niagara Falls, 1988, 2019

Lodoe Laura: Zinnia, I wanted to start by talking about the large-scale photographic triptych of your work that was installed on the facade of the Peel Art Gallery Museum and Archives as part of the CONTACT Photography Festival in Toronto this spring. Can you tell me a bit about Yours to Discover and the significance of showing the work at this venue?

Zinnia Naqvi: Yours to Discover is a project I’m currently working on which looks at vernacular images that my family took when they came to Canada as tourists in the late 80s/early 90s, before they decided to immigrate to Canada. They visited various tourist sites around Ontario, but this project deals with three specific sites; Niagara Falls, the CN Tower, and Cullen Gardens and Miniature Village. I’m looking at the apparent symbols of Canadian national values and ideals that are presented at these sites for tourists and newcomers to absorb, come to make their own understanding what Canada is, and how they could see themselves here. I’ve included the original photos from the family album as well as large reproductions, and made still-life set-ups in my home studio. To point to some of the symbolism or values that I am considering from each site, I’ve included some of my research as well as children’s toys or board games which also tend to teach certain values that are similar to that of the site. The first iteration of this project is currently on public display at PAMA Peel Art Gallery, Museum and Archives in Brampton, Ontario. However I am also currently working on expanding the project.

I was approached by PAMA Peel Art Gallery, Museum and Archives last year in which they asked me to create photos for the front façade of their building, which would be also be featured as part of Contact Photography Festival in Toronto. They were originally interested in some of my past work that uses archival imagery of migrant families and interacts with the family archives. However this was my first time making such a public work, and I’m thinking a lot about the politics of putting brown bodies or seemingly “ethnic” faces on the front of a public building, and what that actually says about the institution it is part of. I think a lot of institutions are doing this in hopes of reflecting more accurately the community they are serving, but often it does not accurately represent the active politics or governance of that site. Brampton has a very large South Asian population but there is still a certain separation in how the public accesses art spaces. I wanted the public to feel reflected in this work but also not used. The way I chose to balance this dichotomy was by using my own family photos. I feel that because I have a personal connection to the images, I have a certain sense of freedom in how the images get used, and to display them so publicly. The front of their building is also a multi-generational programming space that often holds workshops for children and families. I wanted to make colourful images that they would be immediately attracted to, and relate to the experience of visiting these sites as tourists and newcomers. But also subtly included in the images are references are some of my more critical opinions about these sites and Canadian national values.

Keep Off the Grass - Cullen Gardens and Miniature Village, 1988, 2019

A Whole New World – CN Tower, 1988, 2019.

LL: You’ve frequently returned to your family’s photographic archive as a point of departure for your work. In Dear Nani you engage with photographs of your maternal grandmother, taken during her honeymoon in 1948 in Quetta, Pakistan. In the images, Nani poses for the camera, dressed in her new husband’s clothes. Can you talk about your initial interest in these images?

ZN: As you mentioned, prior to making this project I had a history of using photographs from the family album in my work. I found these images of my Nani in some family albums that my aunt had asked me to repair for her. I had a feeling that I had seen the images before, they certainly weren’t a secret in the family, but it was definitely shocking seeing them again and from the perspective of an artist and image maker. I immediately knew I had to make a project with them because the images were so uncanny and beautiful, but I also knew I had to be very careful in the way I presented them. When we consider gender play or cross-dressing from a western twenty-first century context, it has a very different meaning and context from what my grandparents were taking part in Pakistan in 1948, only a year after independence from England. Cross-dressing at the time, especially women cross-dressing was seen often in cinema and symbolized modernity, independence and liberation. But ultimately these images I found were also personal memories of my grandparents on their honeymoon. I wanted to play homage to the political context of these images but also the intimate act they were partaking in. That’s why I chose to use text and additional images interspersed with the found images.

Nani Portrait, 1952. and Nana Portrait, 1952.

LL: Can you say more about the text that you wrote for the work?

ZN: The text is a fictional dialogue that I wrote between myself and Nani. Since she passed away before I made the project I never got the chance to ask her these images. My mother and her siblings knew about these photos but they also never asked her about them. In the dialogue I am asking her questions about where the photos were taken and why. She answers some of my questions but also refuses to answer others. I wanted to keep this as part of the dialogue because these images show a private moment between my grandparents, and my grandmother was a very private person, so even if we had asked her about them I know she wouldn’t have shared the real story. I wanted to convey the distance in our relationship because there is so much I don’t and will never know about her life, and that is often true with people of different generations. This was also a way for me to explain what is happening in the images but also de-politicize them, and remind the audience of the intimacy of this act of gender play. Although I am projecting a lot of political undertones onto what they are doing, it’s also important to remember that they were just a young couple getting to know one another.

Nani in Safari Hat, 1948. (Reproduction 2017). and Self-portrait as Nani, 2017.

LL: Yeah, I think that’s one of the things that’s really interesting about the work. The imagined dialogue comes in little fragmented pieces, and the conversation never fully satisfies the questions of a viewer. The self-portraits you made for the series are also fragmented, in a way. I’m thinking about the layered image of you and Nani, and your image is obscured, out of focus. In the other images, you show only your torso or your legs. Can you talk about these photographs?

ZN: It became apparent that I needed to put myself into the project, as I am the one contemplating and working with the images. But it didn’t make sense for me to directly imitate the gender-play that Nani is performing. The meaning of her wearing a man’s suit in 1948 and me wearing one today is completely different, and not comparable. However in some of the photos, there are also images of children in the background. I don’t know who those children are because they are not my mother or her siblings, but likely some distant family members. I consider the children bystanders of the performance, curious and wanting to understand what the adults are doing but from the outside. I position myself in the same place as these children, looking at the images and wanting to understand what is happening, but just beginning to grapple with it. So in the self-portraits I am really putting myself in their place. In the garden image I’m directly putting myself in the place of the two little girls who are in the background of the other garden image. For the one image where I am mimicking Nani’s pose I chose to wear a banyan, or an undershirt like the one I used to wear when I was a child, before I hit puberty, which is the same garment that my father still wears under his clothes. It also made sense to obscure my face in this image because I wanted viewers to focus on the reenactment of my gestures rather than my identity.

Self-portrait in the Garden, 2017. and Nani in the Garden (2), 1948. (Reproduction 2017).

Nani in Garden, 1948. (Reproduction 2017)

LL: What about the family archive is so interesting to you?

ZN: I go back and forth with this, and I think I pull different things out of the album each time. When I first started working with the album, I think I was interested in helping bring to light the importance of people’s individual stories. I did a project called Past and Present in which I was working first with my own family archive and later with people from my community. It was really generative to see my subjects pull photos out of a dusty shoe box and tell me the story behind them. And for me to later work with their image and then produce a work out of it, I think it gave them a moment to reflect on their own family history and the importance of what they’ve overcome. The same has been true with working with my own family albums, but my feelings have also changed a bit with each project.

With Dear Nani, the photos I found were so striking that I knew I needed to work with them, but I was and am very protective of how they would be seen and in which context. With some of my newer work like Yours to Discover, I think at this point I’m really using my family photos as a starting point and a place for me to read deeper into vernacular images. I could have sought out other family images or images from a public archive, but I chose to stay with my own family images because it sets a limit on what I have to work with and activate. At the same time, because I know who’s in the photos and who has taken them, I do feel a certain sense of agency in how I interact with or further animate the photos. I think ultimately, in a world that is so saturated with images it’s helpful for me to go back to a set of photos that are concrete and finite as a place for inspiration. Even though I have used them for many projects, there is a lot I can read into and get out of these images.

Vanaja Ganeshan, Kondavil, Jaffna, Sri Lanka. 1977.

Installation views in Trinity Square Video's vitrine space, Toronto 2017.

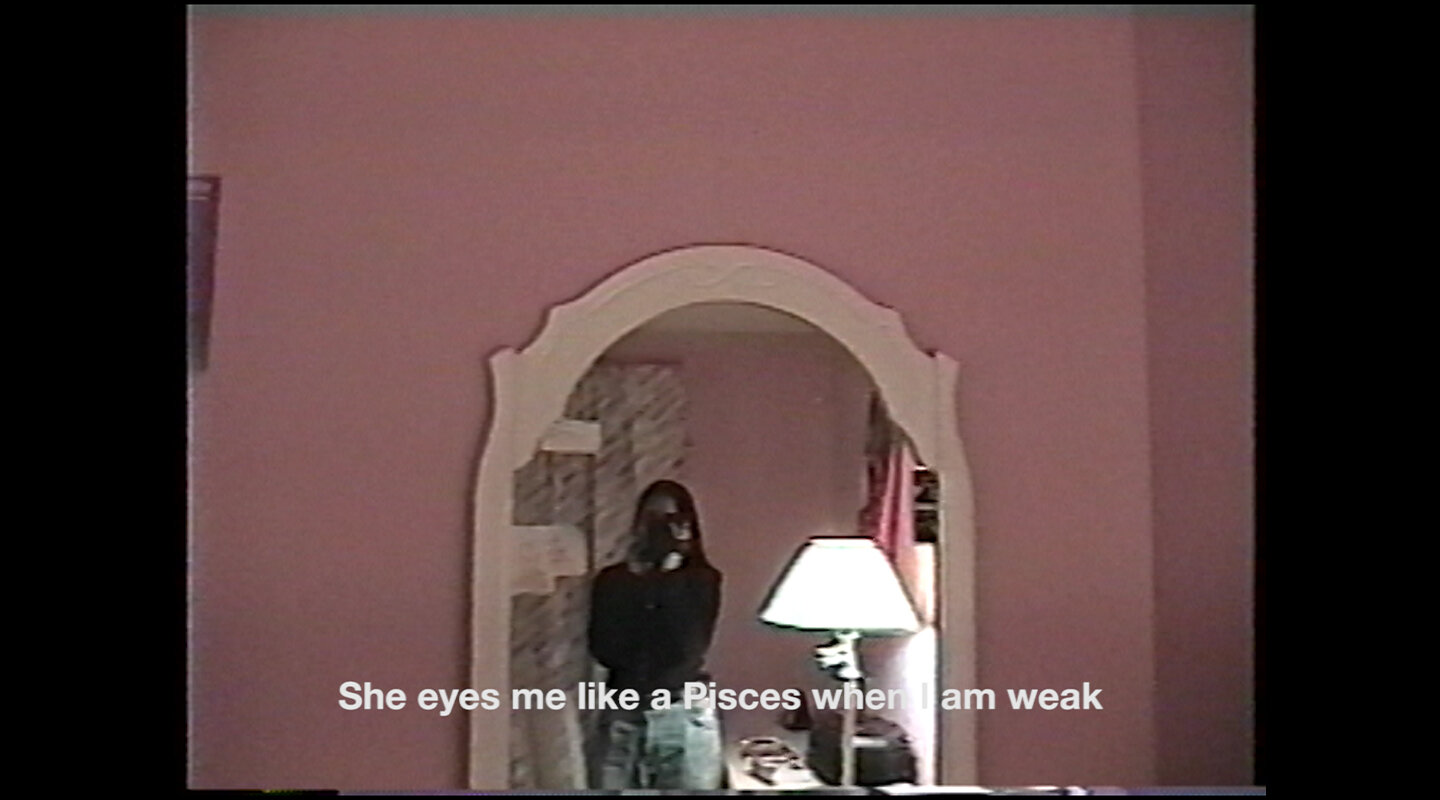

Stills from Heartshaped Box, 2016

LL: One of my favourite things you’ve made from your family’s archive is actually not a photographic work, but a video work. Can you tell me about your process of making Heart-Shaped Box.

ZN: This was a funny work to make because I had just gotten some cassette tapes of home video digitized and was going through it and watching, sometimes with my family. I stumbled across this scene of me and my sisters, of them singing Nirvana songs and teaching me the lyrics. It was a very surreal thing to watch because obviously I’m too young to remember these moments, but at the same time I do remember the lyrics to these songs. It is obviously strange to see such a small child singing such dark and intense songs. I knew I had a certain affinity to Grunge music but I couldn’t exactly remember why. Watching these scenes clarified and confirmed some things about my identity that I hadn’t been able to articulate before. I put together a cut of the footage and made a short video. Then cheyanne turions asked to show some work in the vitrine space of Trinity Square Video. I sent her the video and she loved it. Obviously it resonates with a lot of people who came of age in the 90s. It was really fun making an installation out of the work, but most of all seeing people’s different reactions and responses to it.

LL: What are you working on now?

ZN: I’m still working on Yours to Discover. The three images I made are part of a larger body of work which I am expanding now. This is also part of my thesis work for my MFA at Concordia University in Montreal. I’m looking forward to finishing my degree with this new work.

All images © Zinnia Naqvi