Q&A: SANDIP KURIAKOSE

By Lodoe Laura | May 16, 2019

Sandip Kuriakose is a visual artist working primarily with photography, text and publications. The focus of his work has been an examination of power structures, in the production and circulation of intimacy in sexual and social media interactions. Based in the ethnographic, archival and biographical, his practice mines different visual cultures and found material to understand the failure of systems and the production of counter-systems that bear a glitchy memory of the original. He takes material from public forums: legal documents, newspapers, magazines and social media, and places these in conditions where they play off each other so that new forms of reading can be realised. The manipulation and re-use of images collected from these sources is, in many ways, the premise of his visual practice. This overlaps with his use of collage as form, that simultaneously ‘destructures’ and ‘restructures’ material. In its ability to archive and flatten the mark-making process, collage then becomes that which it seeks to represent.

He graduated with an MVA (Painting) from MS University, Baroda (2014) and a BFA (Painting) from the College of Art, New Delhi. Shows include In Search of Baba Singh, UCI, California; Against the Order Of, Clark House Initiative, Mumbai; FotoFest International 2018 Biennial Central Exhibition INDIA - Contemporary Photographic and New Media Art, Houston; Regimes of Truth, Gati Dance Forum, New Delhi; The 6th European Month of Photography, Das Foto Image Factory, Berlin; Art For Young Collectors, Galerie Mirchandani + Steinruecke, Mumbai; and United Art Fair, New Delhi among others. Residencies include Clark House Initiative (2018), CONA Foundation (2018), TIFA Working Studios (2018) and the Summer Residency Program, School of Visual Arts (2013). He lives and works in New Delhi.

Lodoe Laura: Sandip, in your work, you are constantly pulling apart and restructuring media. You’ve used images–personal and public–, text, and digital glitch as a form of collage. Tell me about this practice, and how you are taking new meaning from the material.

Sandip Kuriakose: I stumbled onto collage as a form of articulating ideas. Through my formative years at art school, I liked sketching but I felt it to be laborious. This was because I was always fighting the urge to not be constantly driven by technical skill. Collage in comparison felt lighter and more immediate, a means to an end. It allowed me to process ideas while simultaneously compressing production time. Since my childhood, I have been deeply invested in popular culture and its relationship to mass-produced publications like newspapers, magazines and books. So drawing from these images seemed like a natural progression for my practice. By skewing the literalness of these images, an intervention could be made and a conversation could be imagined with the larger public. Through my undergrad studies, more than drawing I was interested in plucking images from magazines, old books and family photographs to make image-text combinations that were somewhere between Dada-ist collages and advertising imagery. At art school, this interest progressed into looking at construction sites. Their transitory nature and state of being incomplete drew me to them. Delhi was spilling over with construction equipment and this peaked somewhere around 2010 with the culmination of the Commonwealth Games. Large parts of the city were covered with looming creatures fueling a monstrous spurt in development. The city itself felt collage-like: broken down, restructured, old chunks making way for the new. In July 2009, a large accident took place on one of these construction sites. While I was reading articles about this in the newspaper, the idea for a series of works titled ‘Accident At Delhi Metro Construction Site, July 2009’ (2010-12) occured to me. It was here for the first time that I was able to conflate my interests in text, image, collage and appropriation in a way that I had not earlier.

LL: The final work is a photograph that is an abstraction–a sort of collage. It involves both the digital and physical layering of physical objects and images. Tell me about your process of making.

SK: As previously mentioned, the photographic prints that encompass Woh bhi line ka tha are inspired by encounters I had in spaces like parks, public toilets, and other cruising spaces. Images taken from these spaces are fictionalized and used as atmosphere for objects foraged from these sites. The juxtaposition of object with space helps create what José Esteban Muñoz describes in his seminal book ‘Cruising Utopia: The Then and There of Queer Futurity’ as a kind of utopia for an ‘ideality that will never be attained’. This ephemeral arrangement of objects and memories from these spaces map out a mise-en-scene of what could have been. The images flit between the real and the imagined, the plastic and the potent. I am mostly taken by the potential of these spaces to switch between the real and the imagined, what is visible and what isn’t. Cruising in its essence only bears witness to those that participate in it and in that, survive in public spaces that are otherwise inhabited by folks who don't or are unaware of its presence.

In terms of making, it is a three-layered process. I begin, as already mentioned, by taking photographs along with collecting random objects found in these spaces (parks, gardens, and public bathrooms mostly). The visual and sculptural act as evidence of sorts, abstracted memories picked up on site. This is followed by digitally teasing these images to create backdrops for the final image. This is where new fictions are created, imagined possibilities that flit between the real and the imagined. The last step involves juxtaposing these altered images with objects collected from these sites to create an installation. The photograph of this arrangement becomes the final work.

LL: You often self-publish you work as artist books. What about the medium of the book is especially interesting to you?

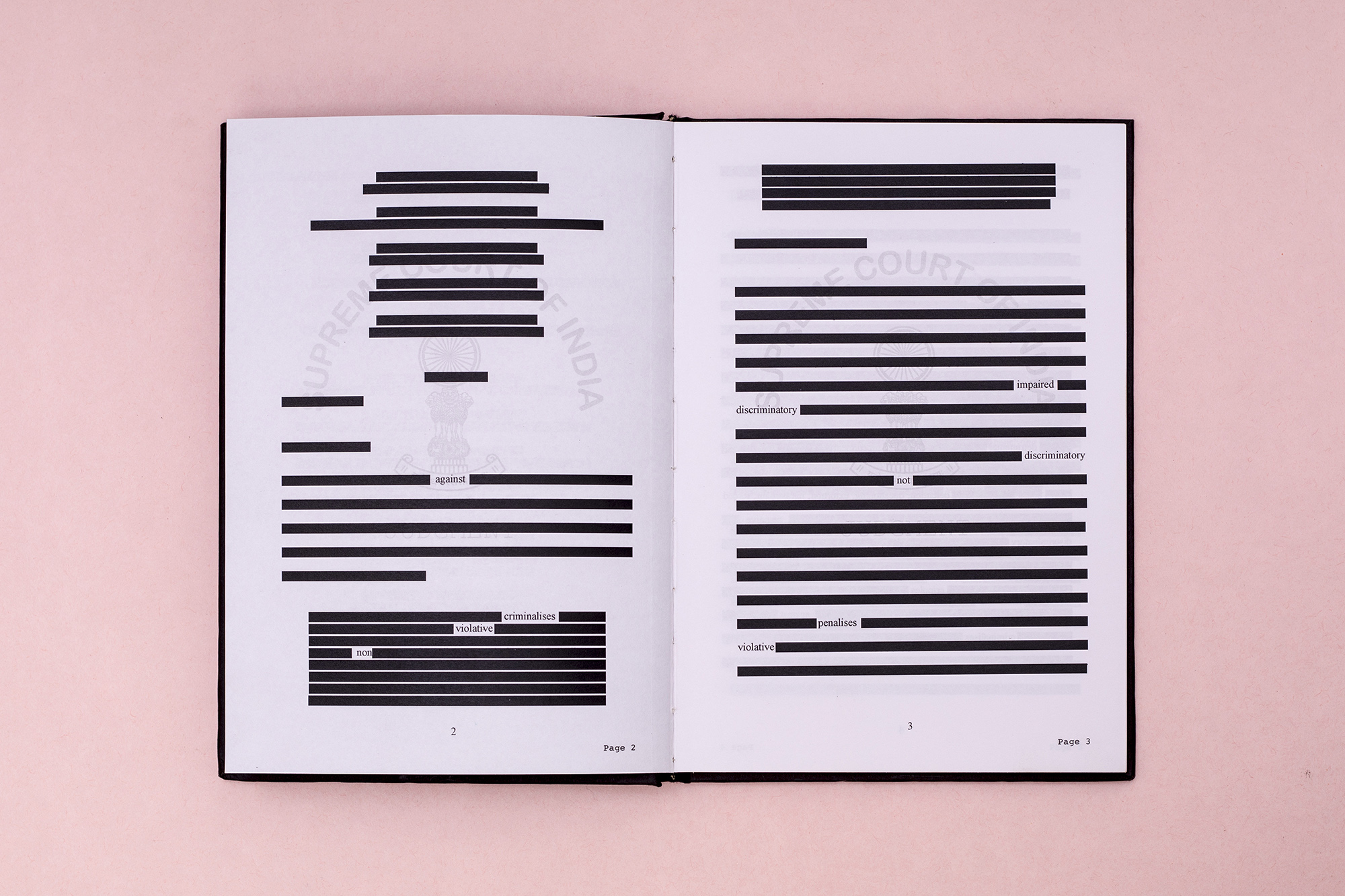

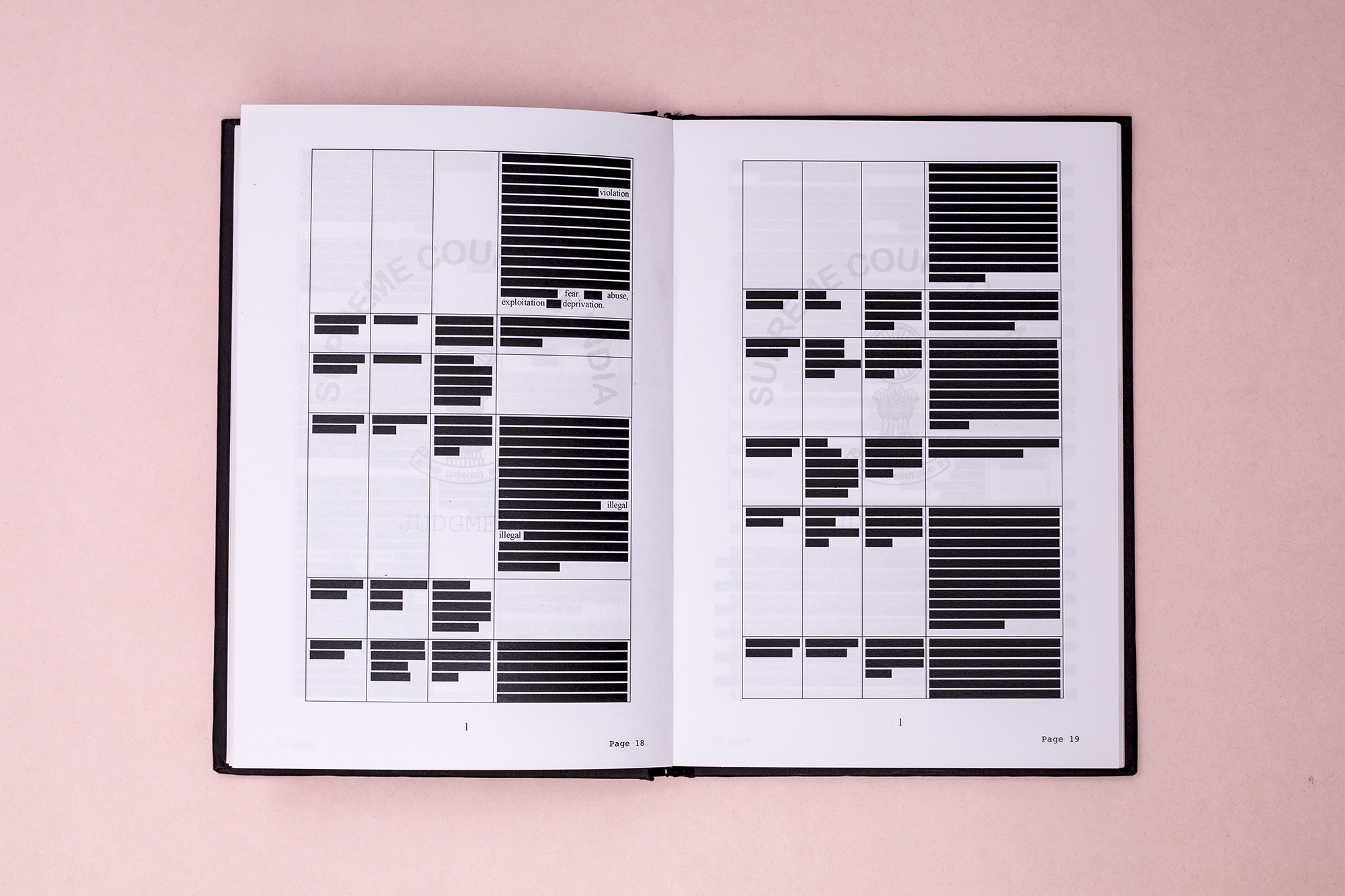

SK: The book as an independent object is exciting for its ability to work with text in a malleable way. Each book can be customised to the specific needs of various materials and projects. This can include taking an entire legal document and reworking its text by blackening everything except the negations as I did with Suresh Kumar Koushal v. NAZ Foundation (India) Trust (Civil Appeal No. 10972 of 2013)

or culling selective sentences and making index card like prints for Notes from Chapter 4. Neurological and Psychological of Richard von Krafft-Ebing’s ‘Psychopathia Sexualis’ or writing a short novel about desire and image-making on the internet as i did with All the right moves. In all of the three mentioned works, text is used conceptually to produce a range of sensations.

LL: Of instincts, tendencies, images, pleasure and conduct is a work that you started in 2016. With the work, you are unpacking ideas surrounding online identity, performative masculinity, and self-imaging. Tell me more about the ideas around this work.

SK: I actually started a version of this series in 2012, while I was looking at the legal document from 2009 that I have previously mentioned. I was taken by how men were presenting themselves on dating websites and apps for other men and the performative masculinities that inhabit such spaces. I was fortunate to have access to my friend and well-known poet Akhil Katyal’s Ph.D. dissertation chapter titled ‘Photographs of Desire: The Profile Picture on Planet Romeo’ (2009). This helped me think through the ways in which desire gets embodied in both spaces and images. The work started off as collages - cut up images of men stacked atop each other. I was unsure about these works till 2016, when the images became more spatial. The collages morphed into objects that inhabited a larger space along with other objects. A lot has changed over the last four years with the internet functioning as a fictional site. There is a lack of linear temporality and empirical space where identities morph into one another. New masculinities are performed and produced relentlessly. This series examines how these images, when taken off these websites change meaning through networks of digital distribution and become physical, tangible objects. The final images are collaged in a way that obscure the identity of the subject in turn producing an allegory for how fictional personas of the self are generated by users of social media.

LL: I’ve heard you describe your work as an examination of power structures. Can you tell me how your work, which involves the circulation of the intimate and the sexual, interacts with larger ideas of structures of dominance and control?

SK: In what was considered to be a significant marker for progress regarding queer rights in 2009, the Delhi High Court read down Section 377 and decriminalized sexual acts ‘against the order of nature’. The legal document submitted to the High Court by the team of lawyers arguing for the reading down of Section 377 was a 105-page document which succinctly spanned ideas around morality, sexual behaviour, and the history of legislation around homosexuality. As a gay man growing up in India, I recall my earliest memories around intimacy and sexual attraction being laced with a paralyzing fear that had its roots in the country's conservative legislation. Adding to this anxiety was the concurring conservatism of public opinion around homosexuality. Reading this legal document helped me conceptualise a larger series of works that articulated ideas around desire and intimacy. The work contextualised these within the external frameworks of governance and legislation.

LL: I want to talk about your newest work, a work that is still in progress – Woh bhi line ka tha. The title translates from Hindi to “he was one of us.” What is the significance of this phrase?

SK: Woh bhi line ka tha, translated as ‘he was one of us’ is a term commonly used in cruising spaces. Public sites where men often engage in sexual encounters with other men become the backdrop of this work. ‘Line’ here stands in for vocation, a choice of activities or even orientation. The series includes a series of digital prints and a book with transcripts of conversations had in these spaces. The title was inspired by a line that came up often in conversations had in these spaces, the crux of which was referencing to other encounters (in third person). A large part of the series is conversations that I had with men in these spaces where they referred to other encounters and many of these began by describing a situation or a man and the fact that he was ‘one of us.’ Here, line becomes evocative of some sort of secret, behaviour, activity, vocation that is referred to code-language like, referring to a man’s sexual habits within these spaces. I was taken by this phrase given how how laced it is with multiple meanings: fairly innocuous-sounding when out of context but simultaneously laden with many meanings in these spaces.

All images © Sandip Kuriakose