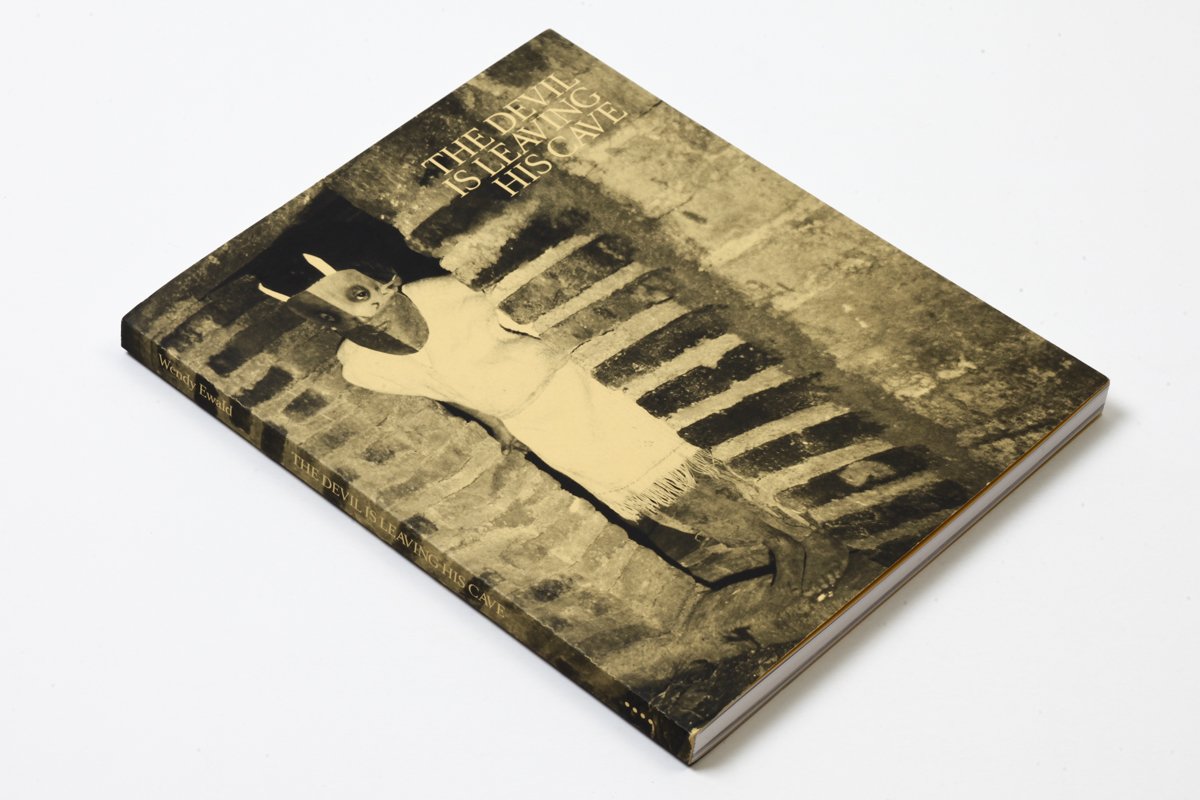

Book Review: “The Devil is Leaving His cave” by wendy ewald

By Kelly Lee Webeck | December 1, 2022

Published by MACK in 2022

8" x 9.65" / 144 pages / OTO Bound Paperback / Essays by Wendy Ewald, Abigail Winograd, and Edgar Garcia.

As an arts educator, I have been familiar with Wendy Ewald's work for over 10 years now. When I started my first teaching position in 2011, Ewald’s book I Wanna Take Me A Picture was a resource I leant on regularly as I developed activities for an afterschool photography program at a local middle school. Her instruction simplifies the technical elements of photography to be understood by young learners and is also about learning to read photographs. Under her guidance, children increase and hone their visual literacy by not only making photographs, but also engaging in writing exercises such as pairing words with images. What makes the work that Ewald does so powerful is that she empowers children to speak for themselves and to tell their own stories.

The Devil is Leaving His Cave is about collaboration between an instructor and students. It is not an educational title or manual. The book does not come with prompts and instructions that can be taken directly into a classroom or provide instruction on how to set up a darkroom in unusual places. While a savvy educator will be able to read Ewald’s text, examine the photographs and recreate similar collaborations, The Devil is Leaving His Cave is more about celebrating the work created by the children she worked with in two projects created nearly 30 years apart. They are connected through the backgrounds of the children who participated.

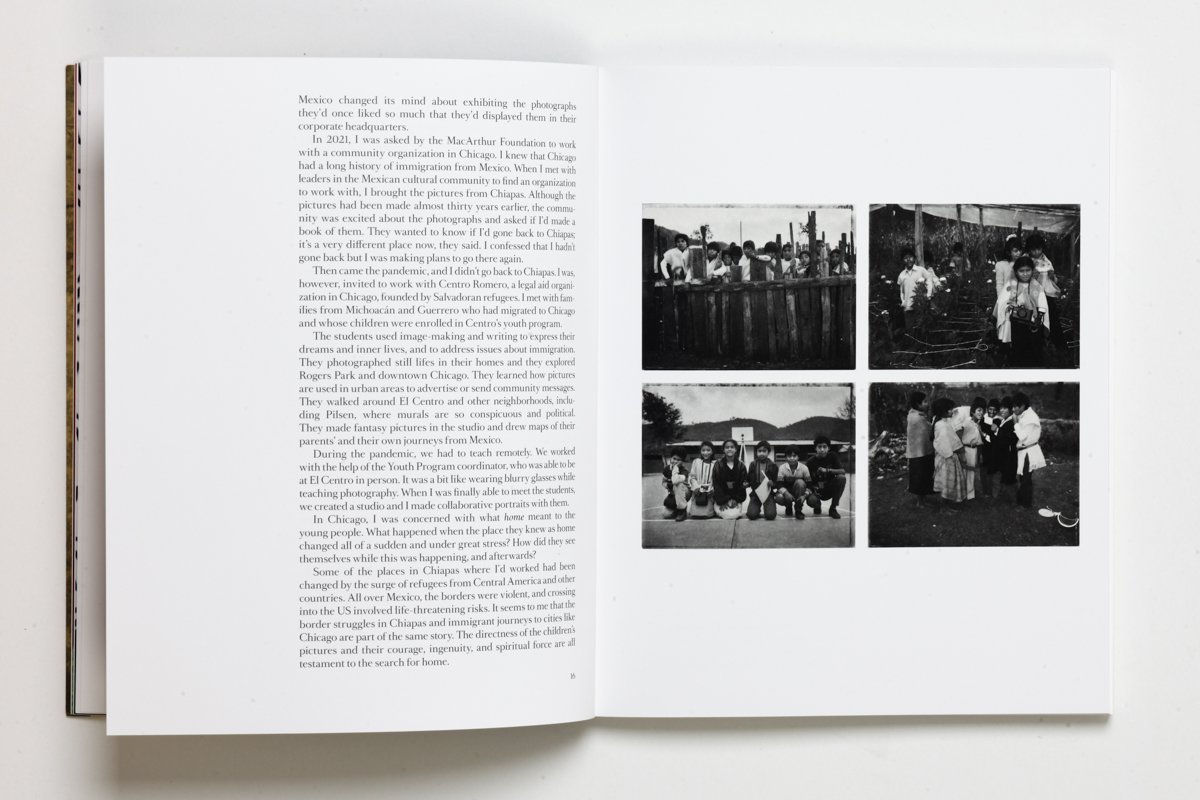

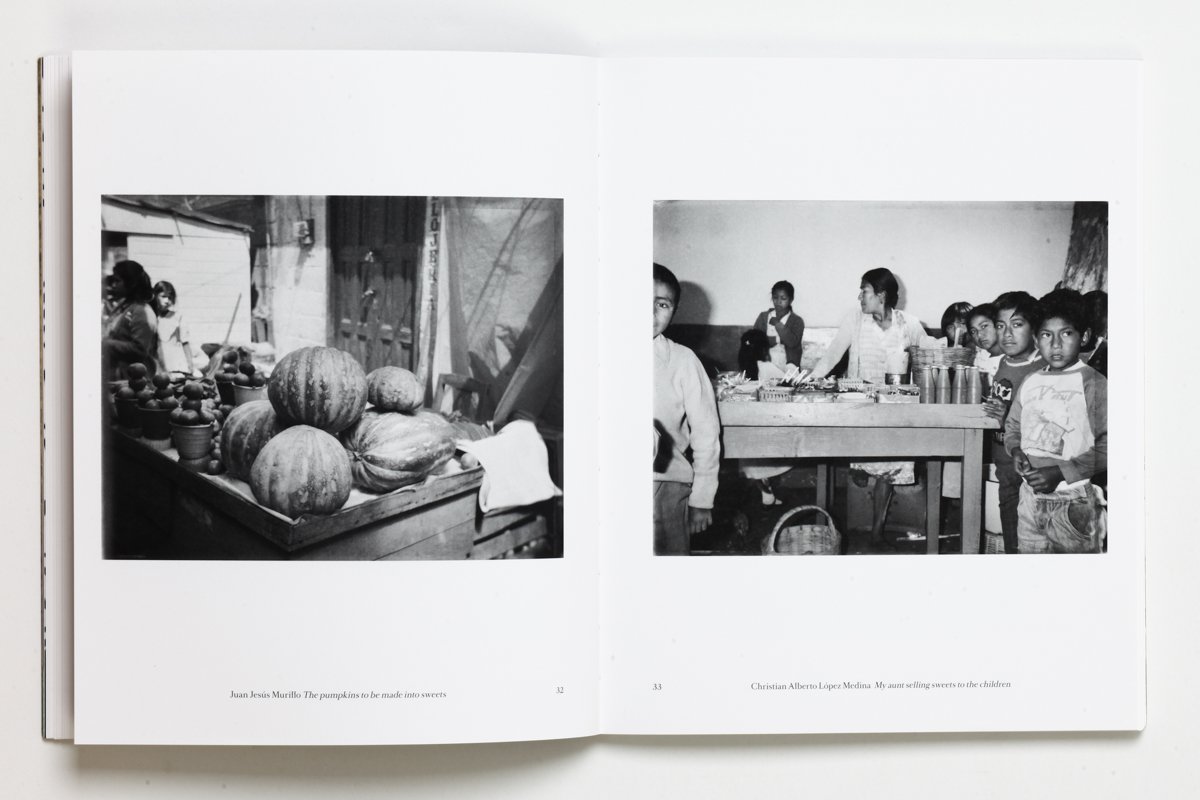

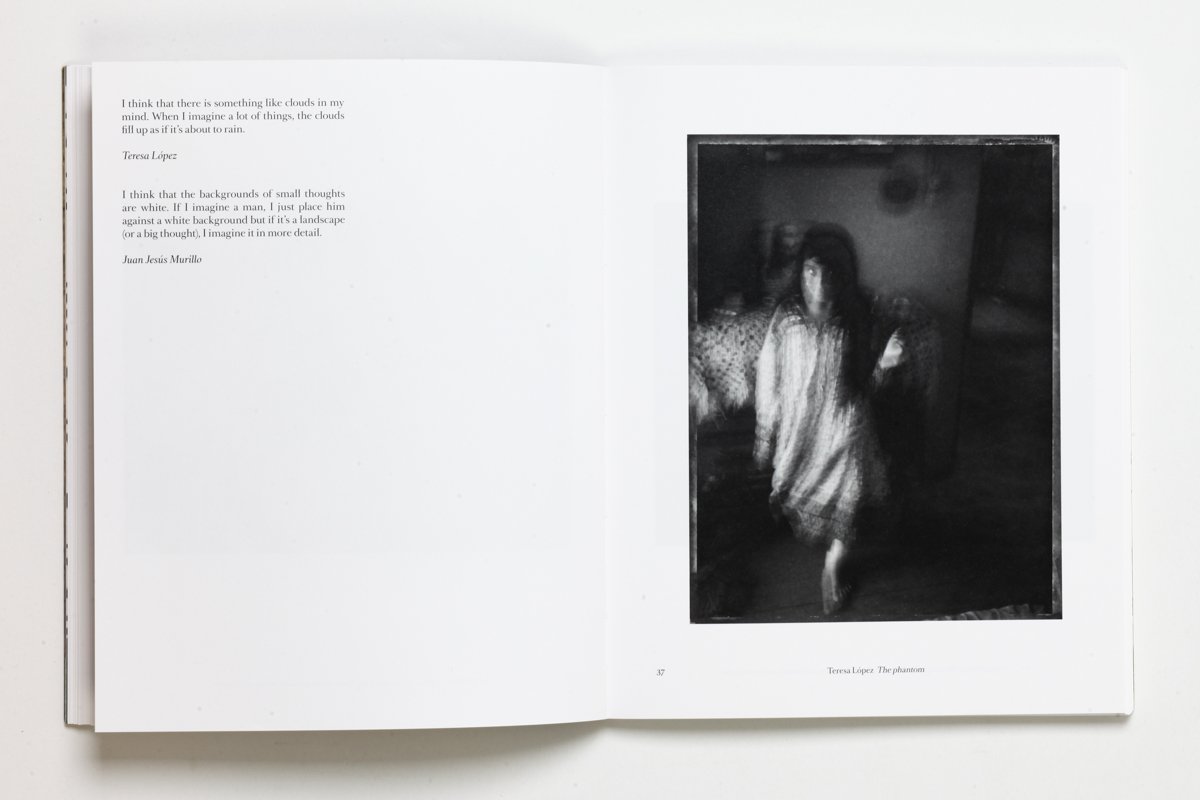

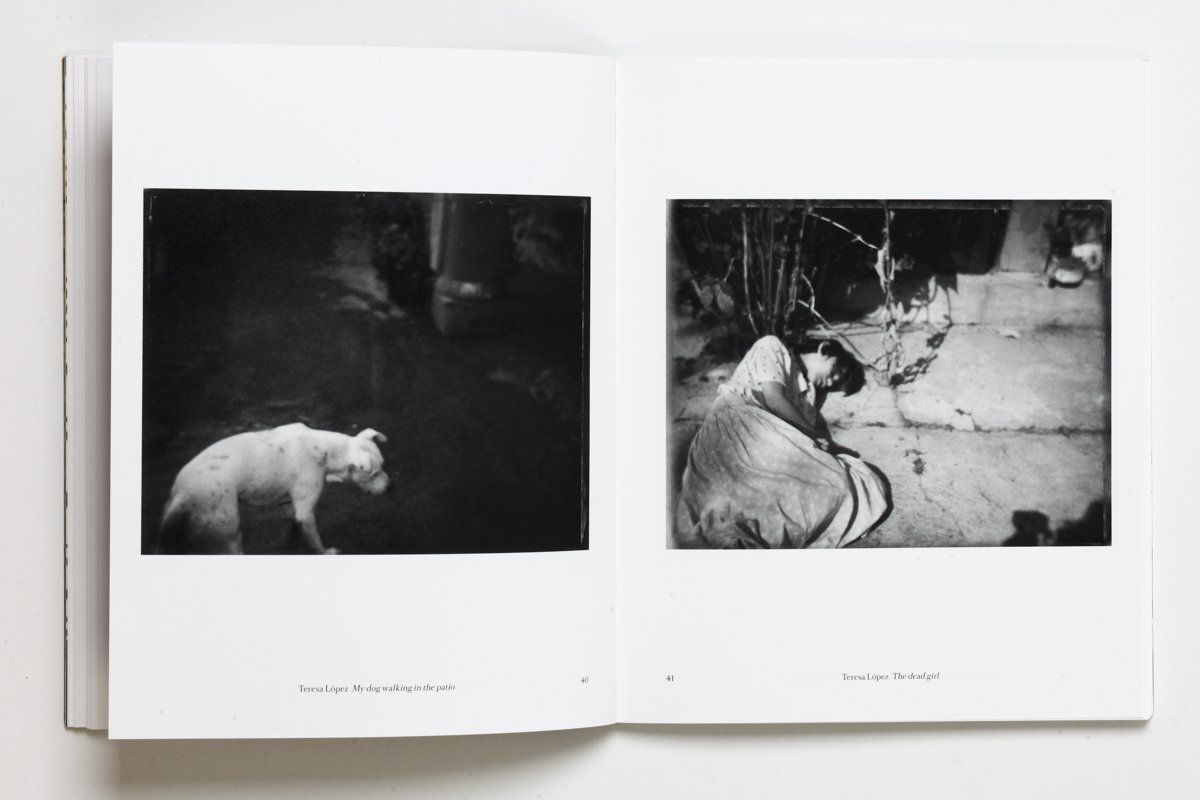

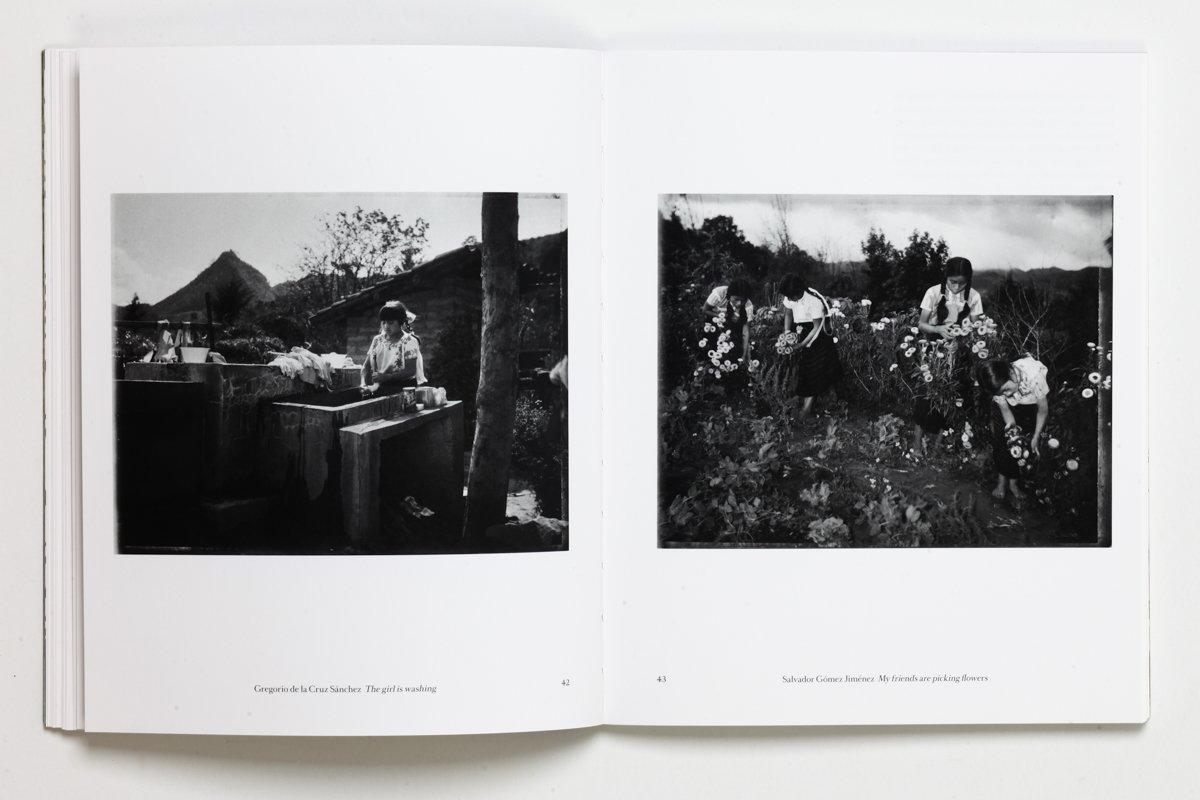

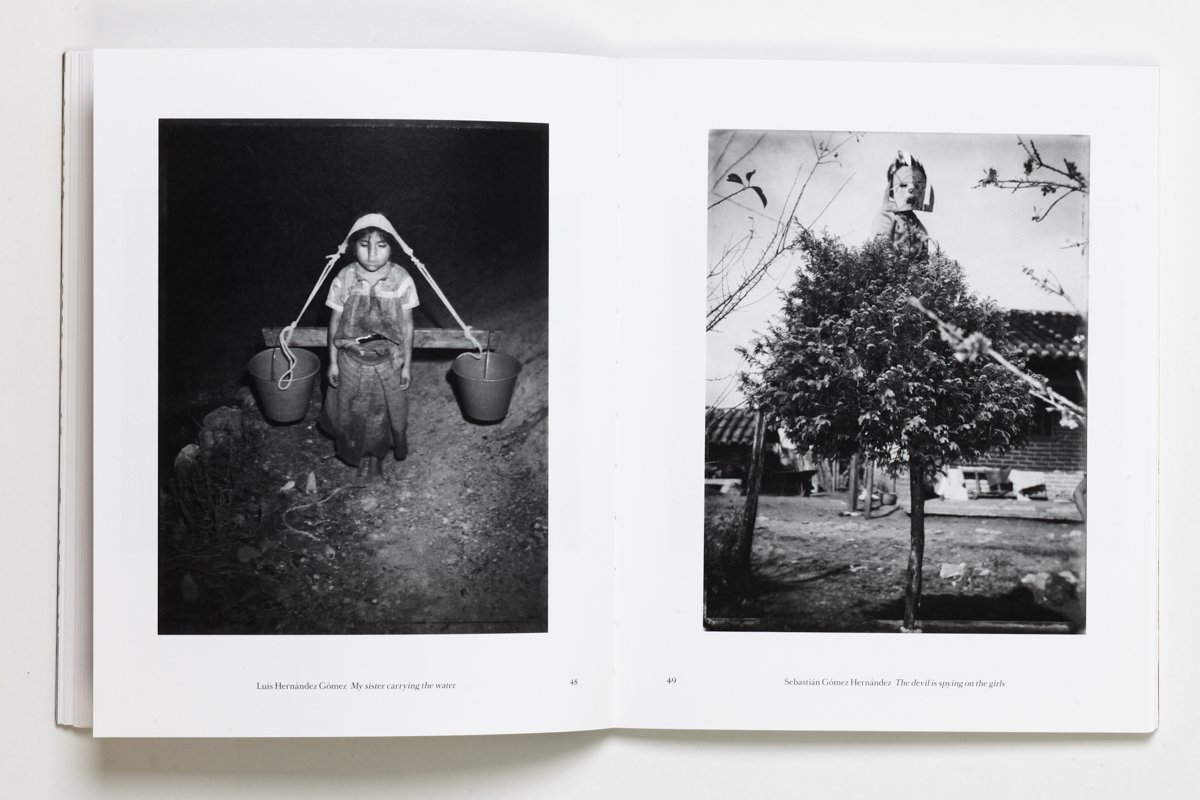

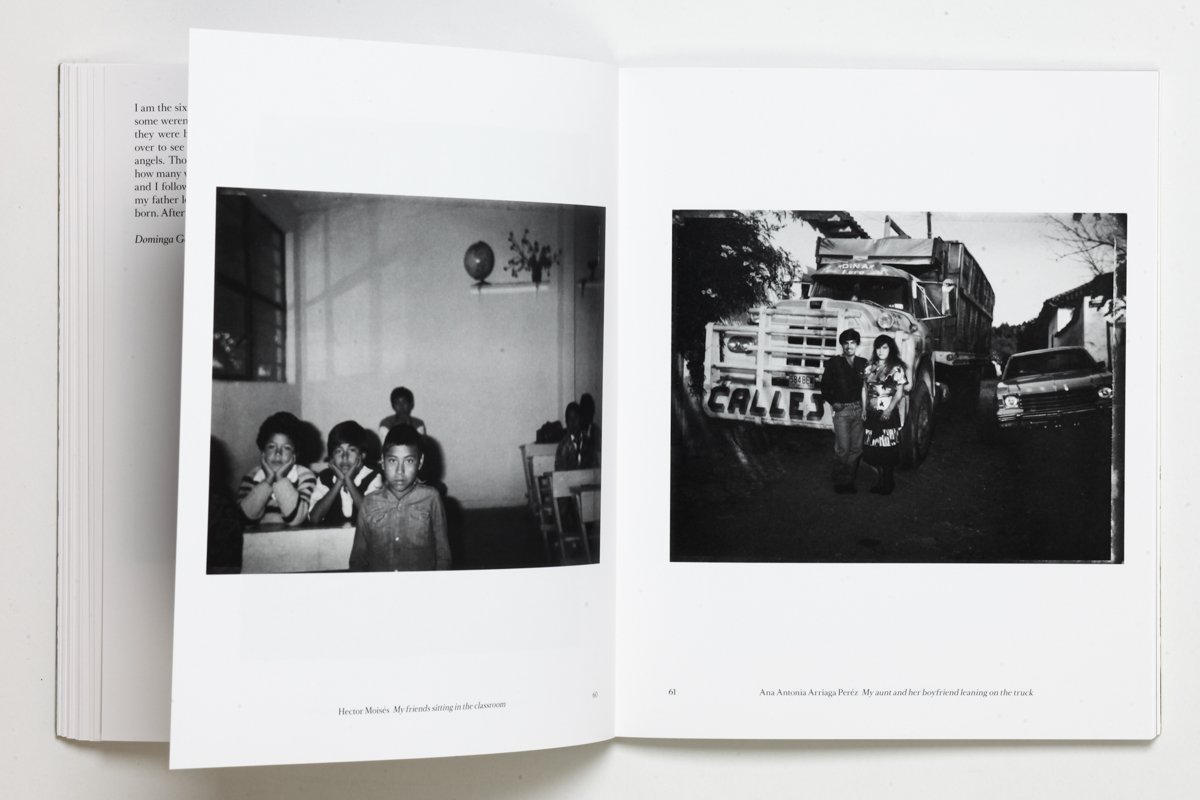

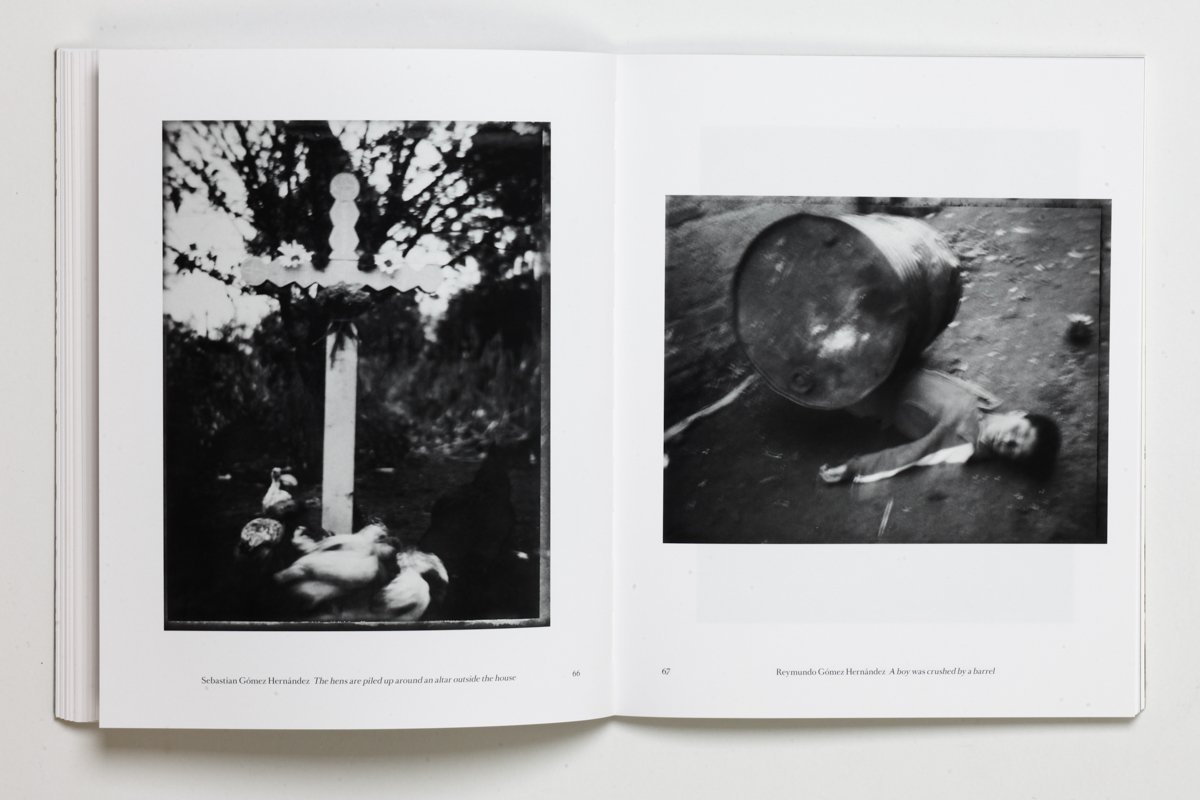

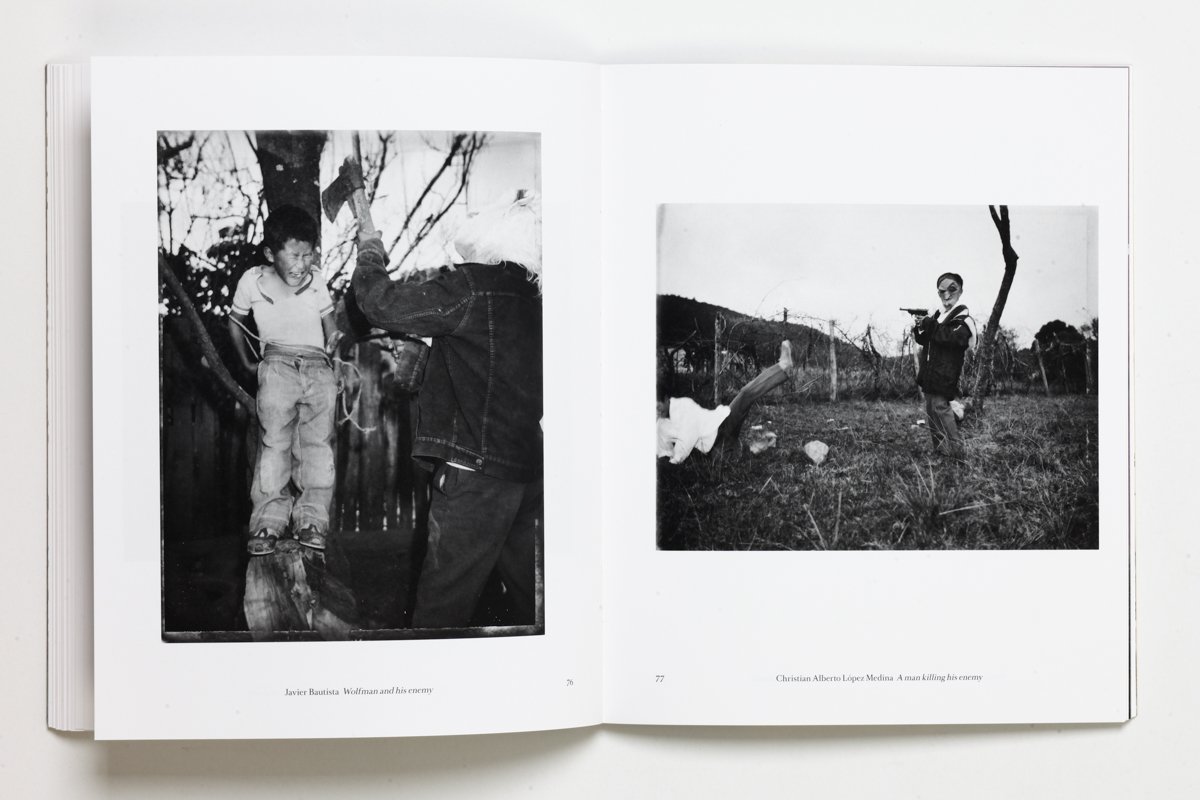

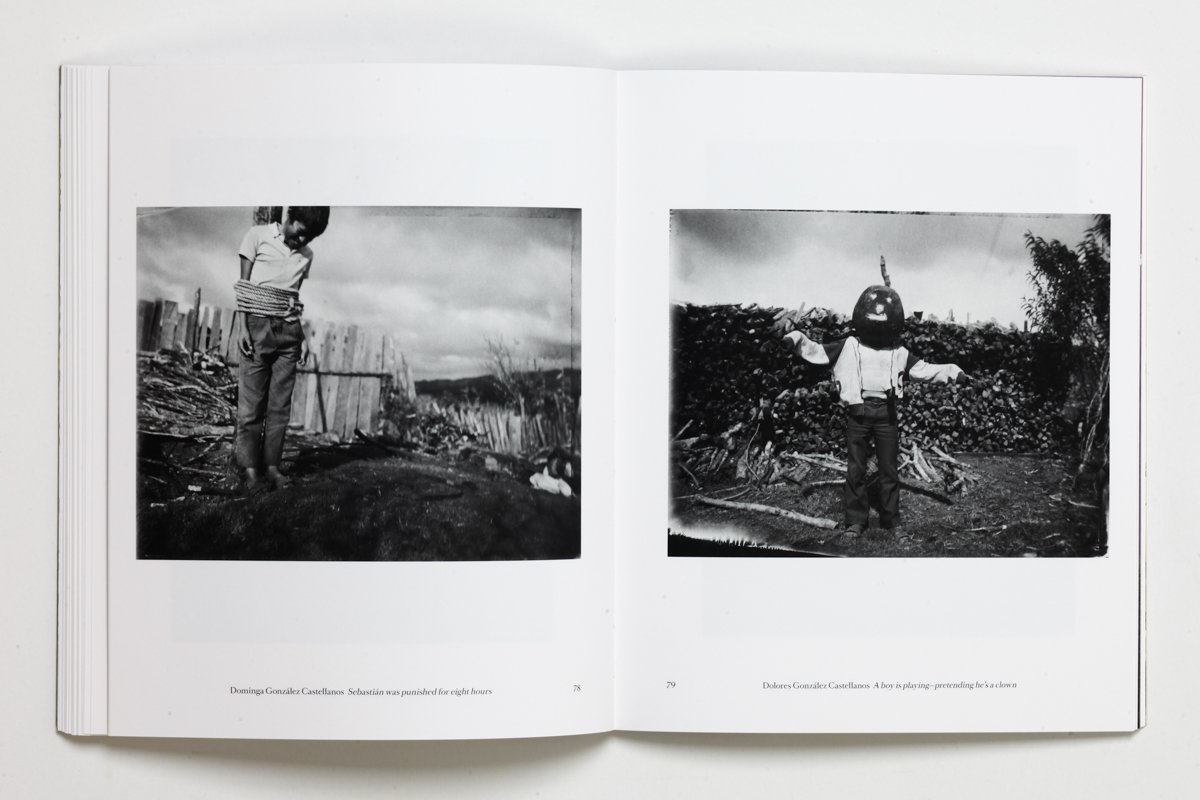

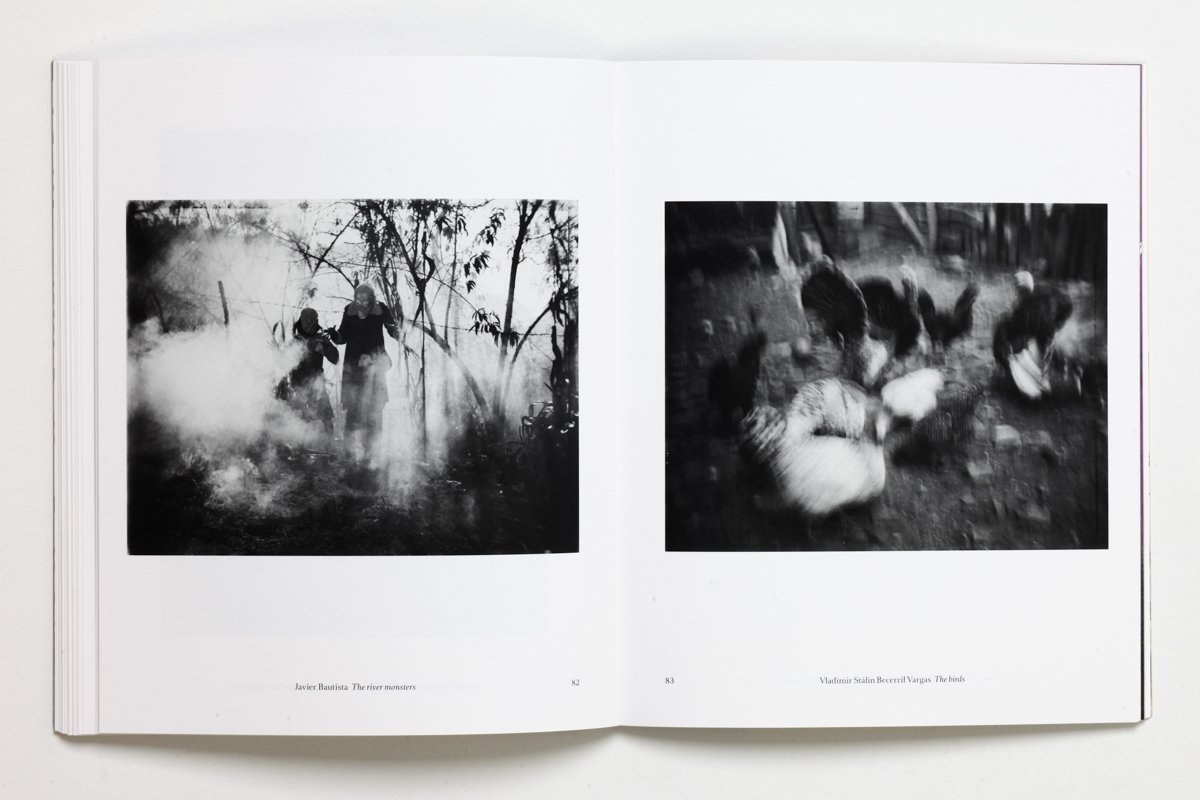

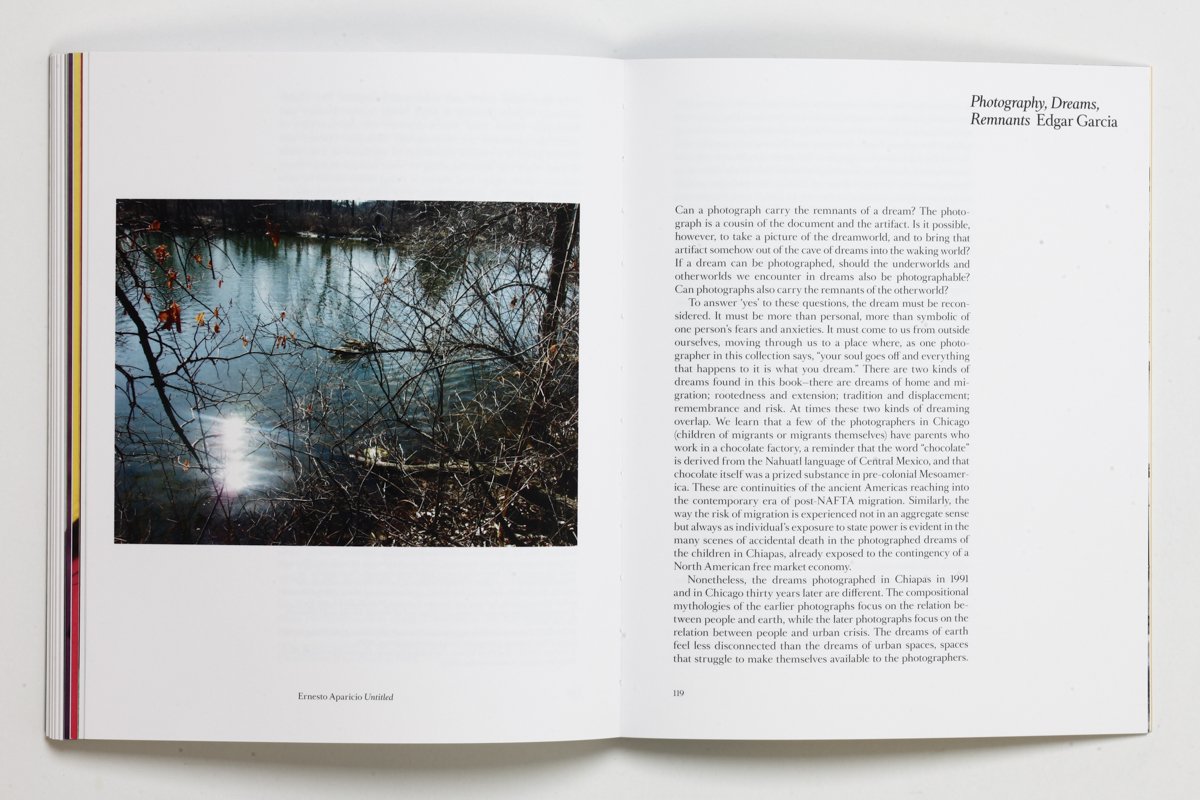

In 1991 Ewald traveled to Chiapas, the southernmost state in Mexico to conduct photography workshops with children in several communities. She asked the children to capture in photographs what they saw around them as well as their dreams and fantasies. They used Polaroid positive/negative film, a peel-apart technology which allows the user to view images nearly instantaneously, a good fit for this project in the days before digital photography was widespread. This medium lends itself perfectly to capturing the elusive quality of dreams, writing the ethereal characteristics of mist and light into its coarse grain. Expressing their ideas, we see homemade masks adorn the faces of children climbing trees and peeking through doorways. Motion blur emphasizes a strangeness of place helping distort the line between reality and the dream world. They also express the dark fears of childhood by performing for the camera. A boy was crushed by a barrel and The dead girl both unintentionally reference photographic history, echoing Hippolyte Bayard’s Self-Portrait as a Drowned Man.

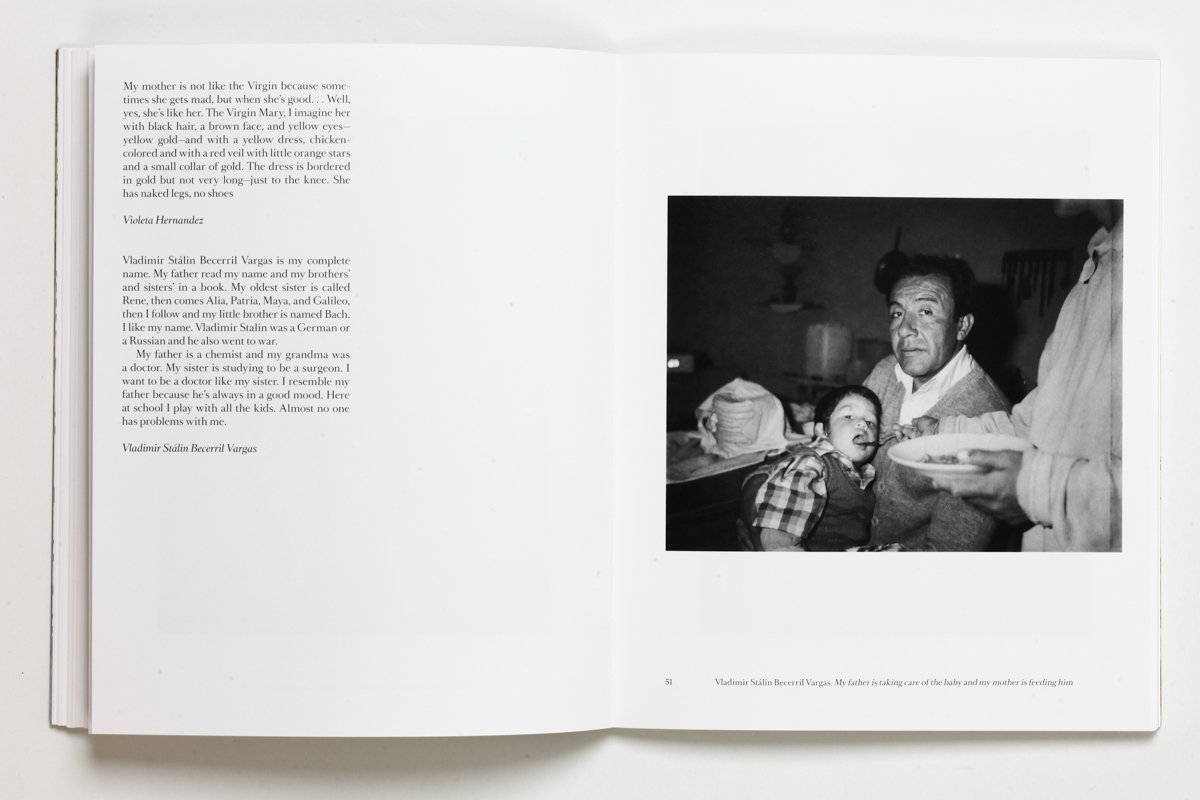

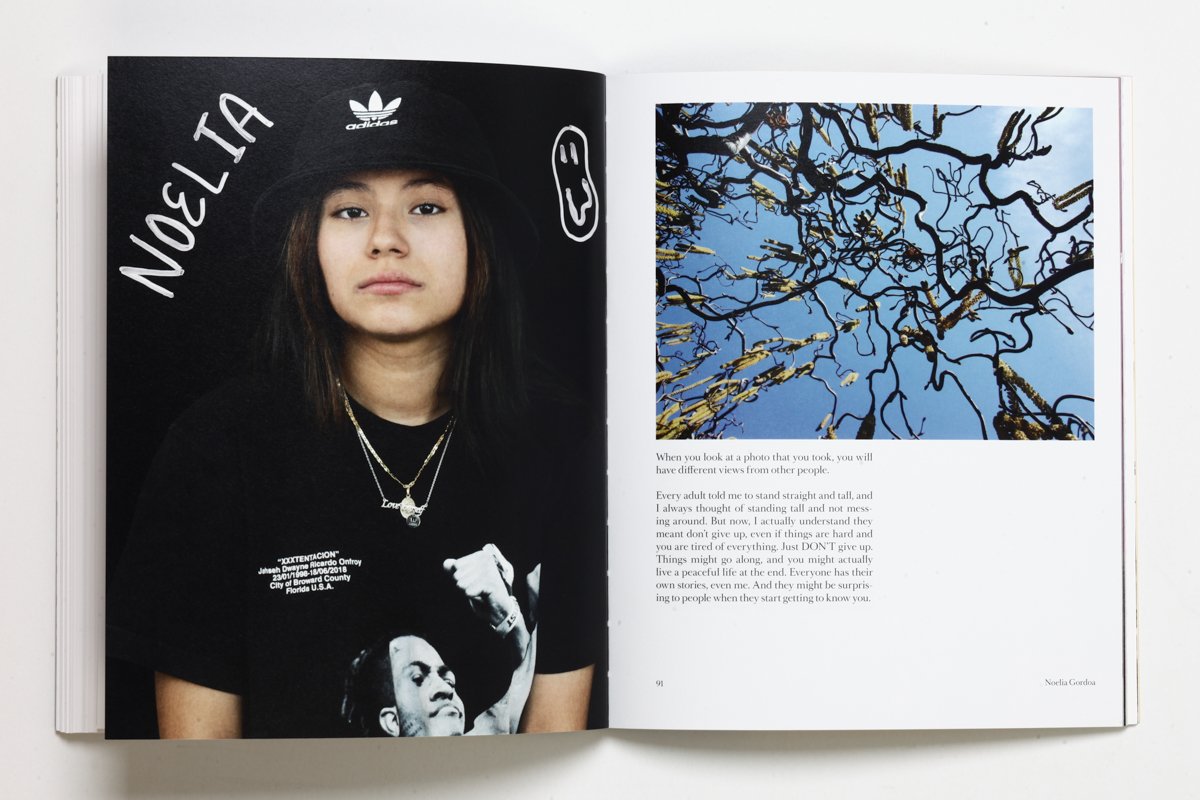

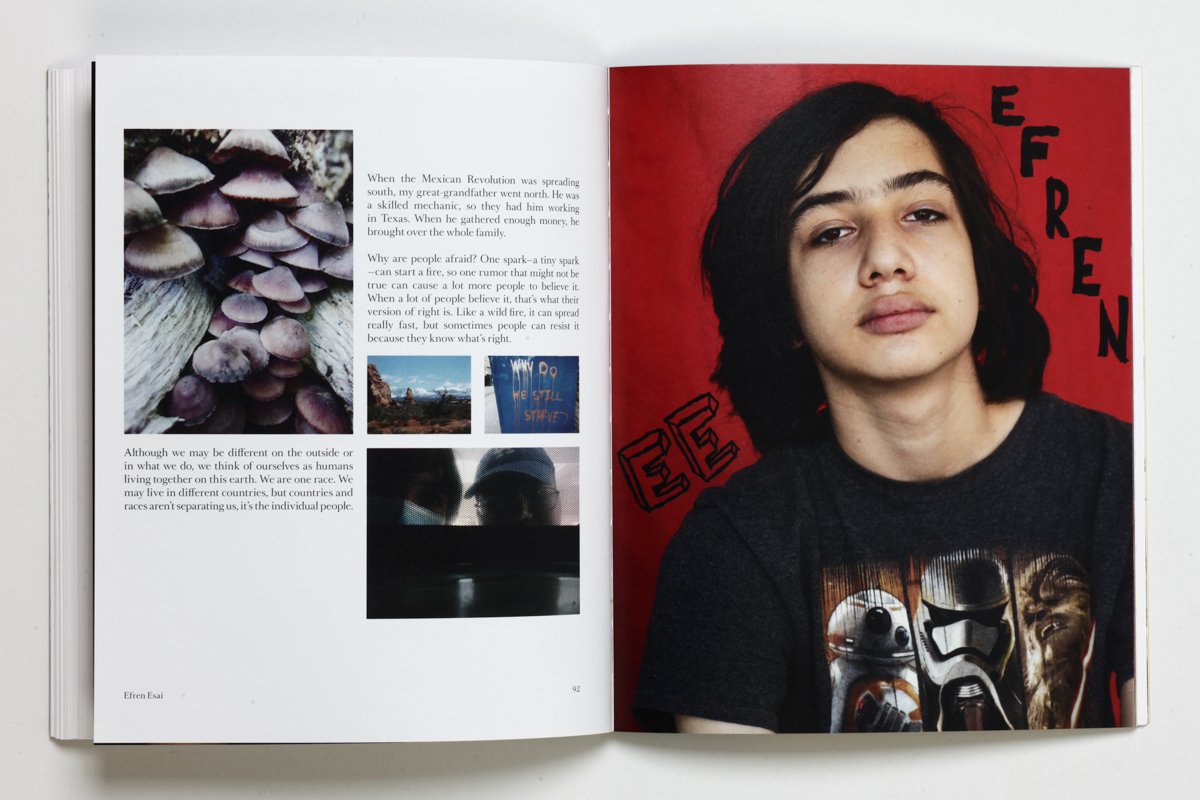

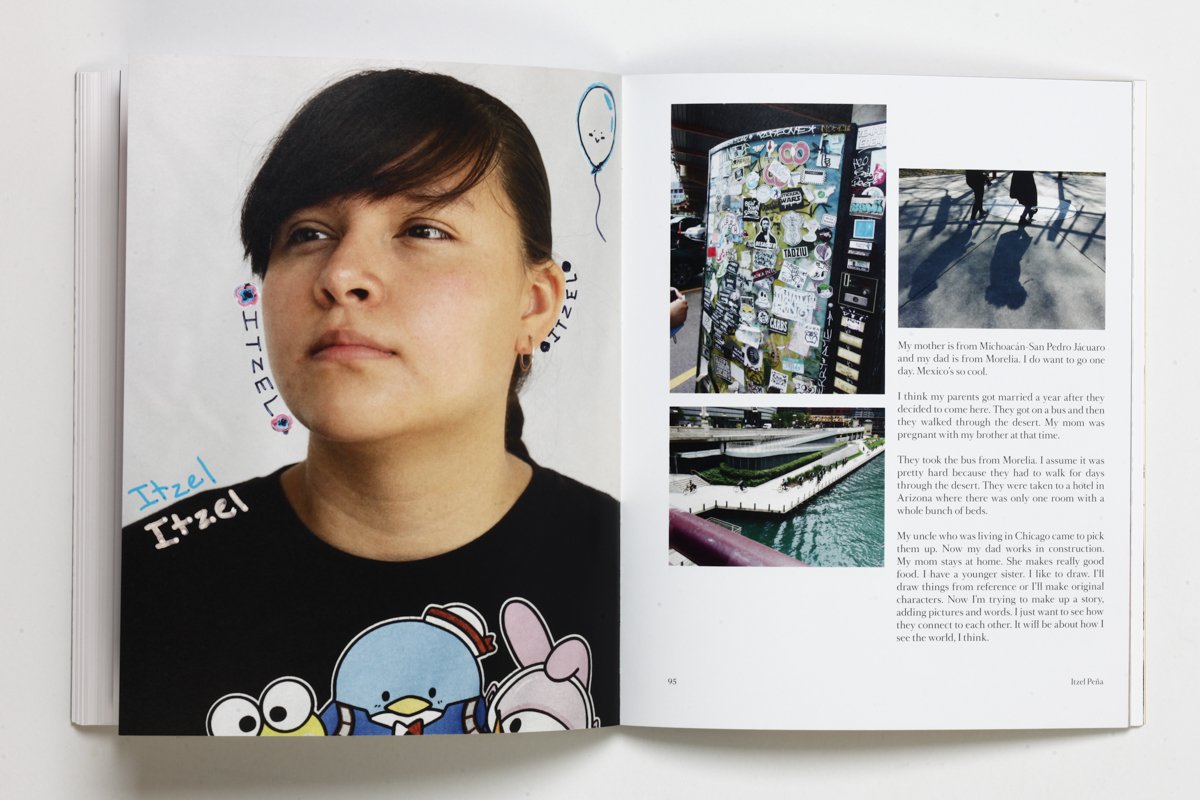

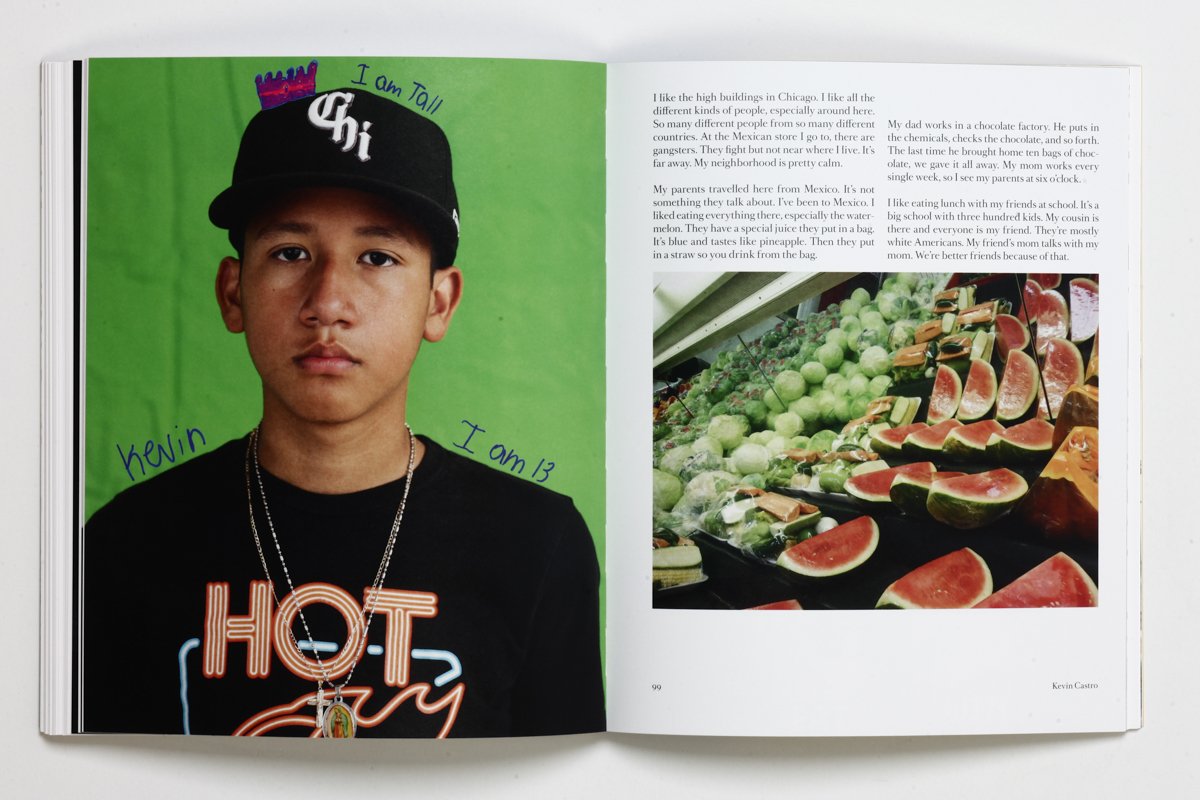

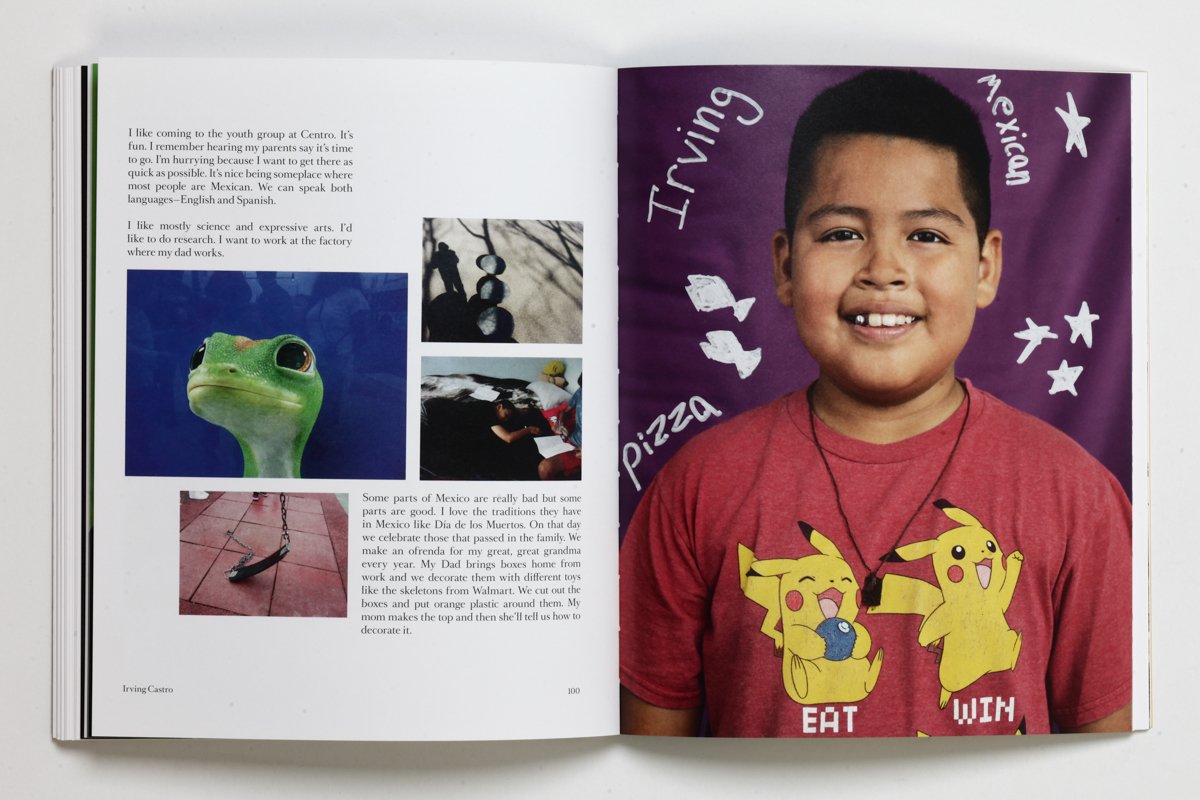

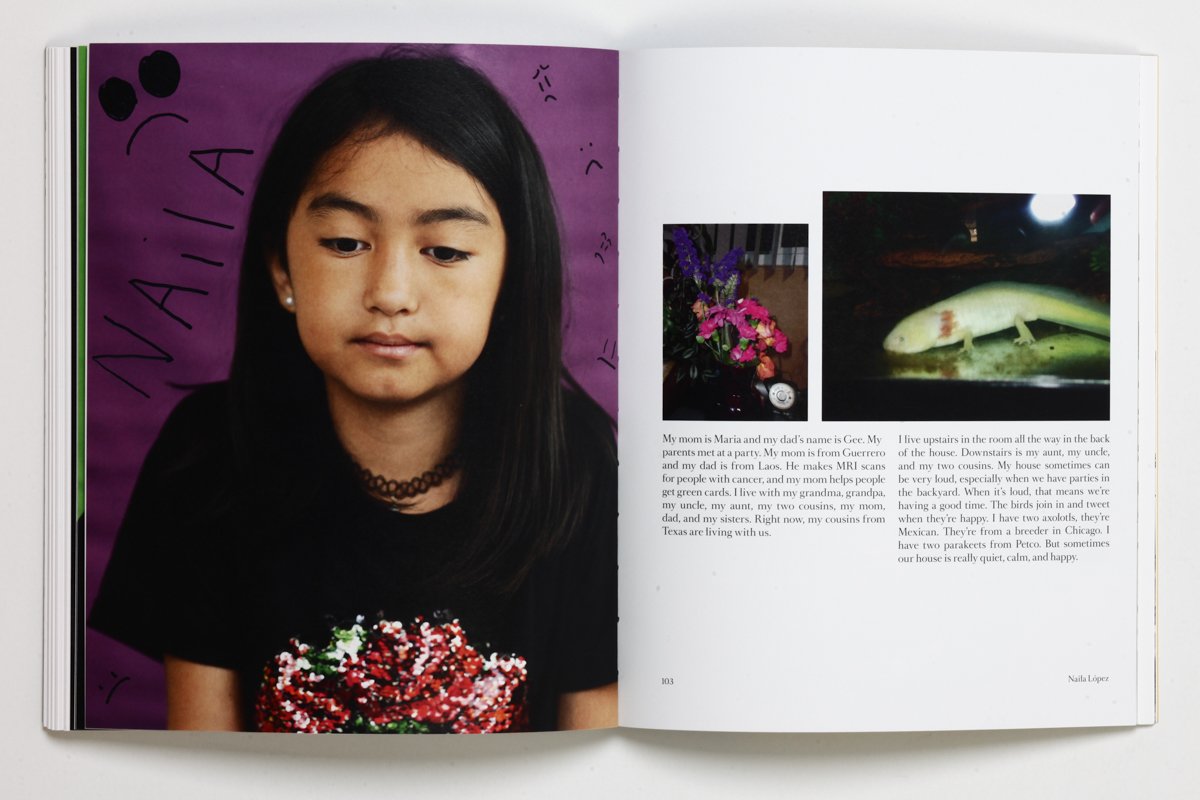

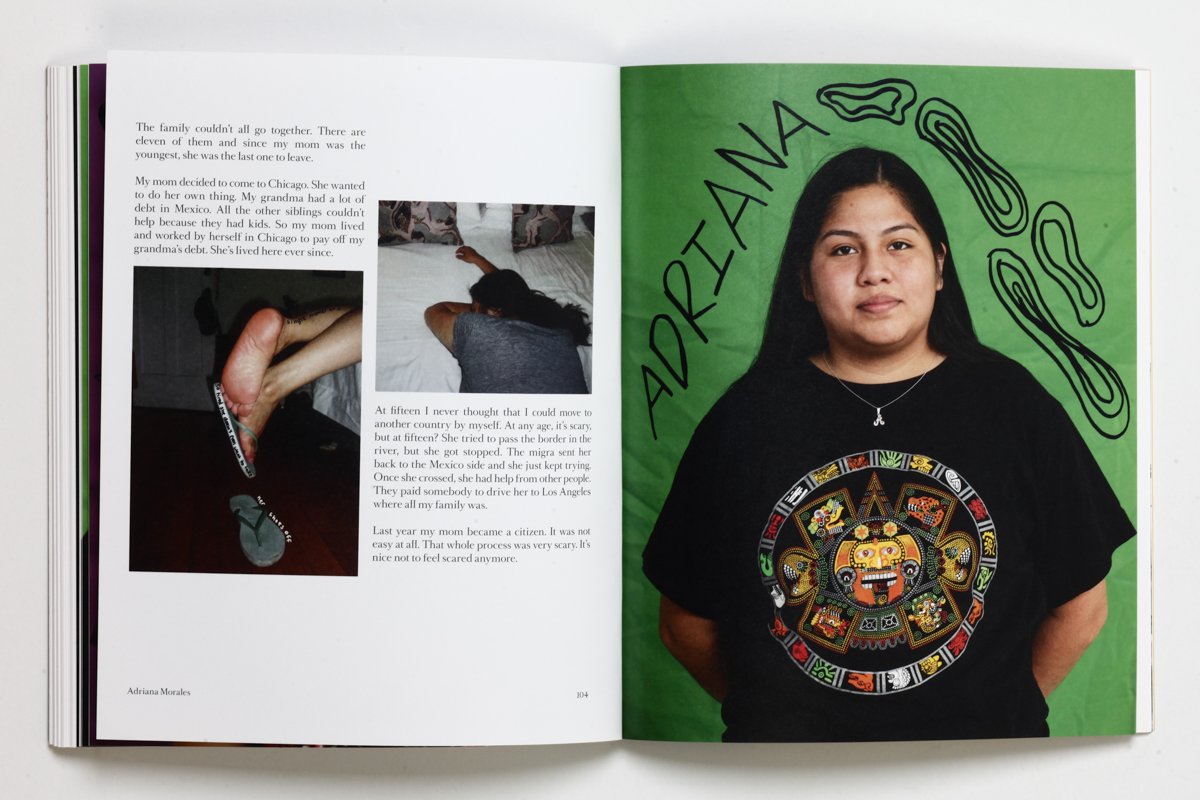

From 2019 to 2021 Ewald worked together with a group of students whose families had migrated from Mexico to Chicago. Since the collaboration happened mid-pandemic, the teaching happened remotely until they met in person near the end of the project. In this section, colorful portraits made in the studio together with Ewald are printed full bleed. These images have been embellished with words and drawings by the hand of the child shown. The visual simplicity of the collaborative studio portrait makes me wonder about the interactions that led to the moment of the image being made. What did Ewald speak to the students about? How were they asked to present themselves? What prompts were they given to adorn the print? These portraits become incredibly powerful when paired with the childrens’ images and writing. We are shown clippits of their everyday life and with this context we begin to get a sense of who these children are and what their lives look like. There are photographs of pets and family, still lifes in the home and neighborhood grocery stores. Shot digitally, these images from Chicago are contemporary and familiar. The vibrant color palettes and the clothing choices reflect how young people express themselves today. The narratives speak deeply about human experiences. The children write openly about the scary realities of crossing borders, family members that were left behind, being held in detention centers and the things their parents do to support them and their family. Also expressed are heartwarming stories of home and family, as well as what they love about the Mexican traditions and culture they brought with them.

The parallels between these two projects are seen in what the children captured and the stories they told. Although visually different, the children depict similar things: family, food, community. They express the uncertainty of the time and setting they are living in by discussing their fears and hopes for the future. Both projects are symbolic of the lives the children have lived and their experiences. There is a darkness within some of the constructed Chiapas images with some photos reminiscent of scenes from horror films. Others reenact violence, such as Wolfman and his enemy, Sebastián was punished for eight hours, and A man killing his enemy. While violence is hinted at within stories about detention centers and border crossings in the work by the Chicago students, it is much more subtle. It feels more distant and not as integrated into their fantasies. It is clear that these children empathize with the results of violence, such as Marastela’s insights about George Floyd’s daughter. These children have faced difficulties but write optimistically about how they move through the world. Naila surrounds her portrait with frowning faces but writes about the joys and difficulties of living in a household of at least 10 people. These contradictions demonstrate their resilience and strength.

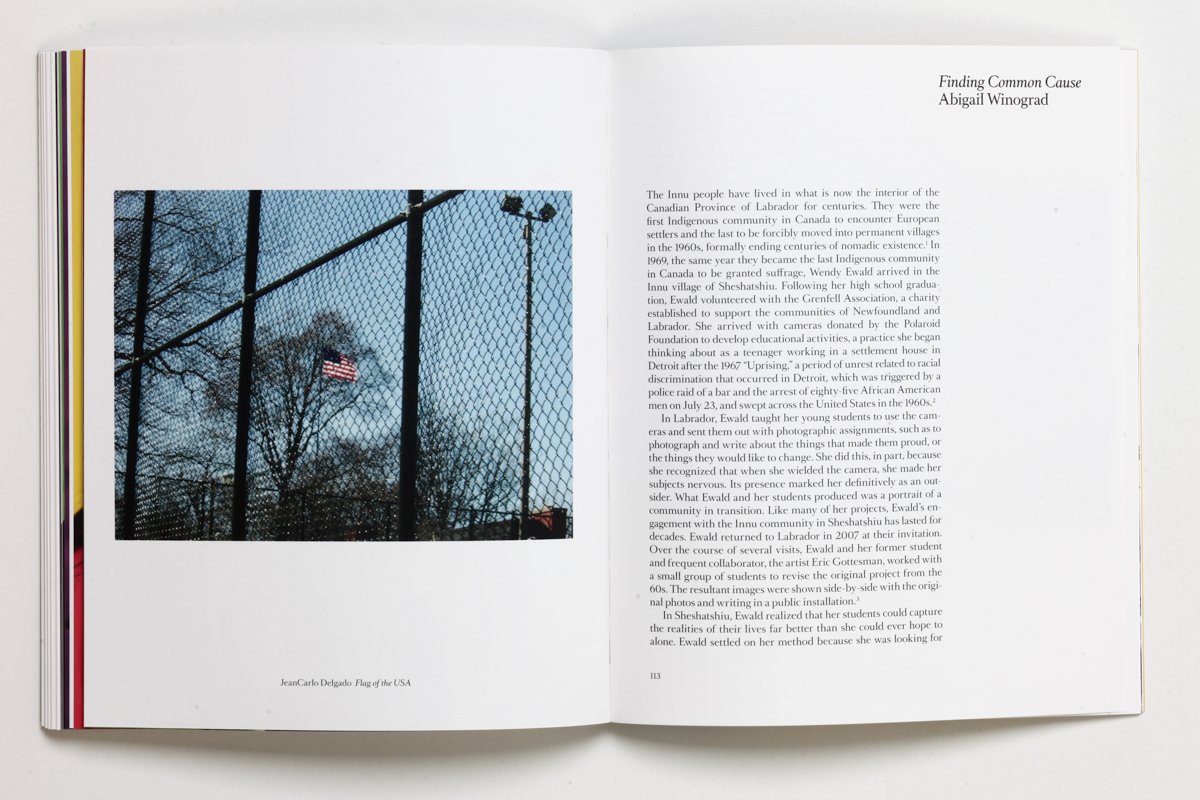

When these projects are brought together in one publication they speak to how observant children are about the world around them. They prove that kids listen and see. The Devil is Leaving His Cave is a beautiful, well sequenced curation of the voices of children whose family stories are rooted in Mexico. Unlike the Chiapas images which could not be exhibited throughout Mexico as planned due to the Zapatista uprising, the Chicago portraits were displayed within the community in a way that pedestrians could see the portraits of the children as they walked by. This book is a platform to celebrate and honor the voices of children who deserve to be heard. The yellow cover invites us in, promising mystery with a title that incites a tingle of fear.

Wendy Ewald is an artist in her own right, and can equally be classified as a community based arts collaborator. Her community focused projects amplify the voices of people whose stories are relatable but not often heard. From Ewald, one can learn how to inspire confidence in children and how to help them find their own voice.

The Devil is Leaving His Cave is available from MACK.