In Conversation: Salman Toor with John Brooks

Salman Toor and John Brooks (left to right). Photo courtesy John Brooks.

On a cool, gray, drizzly October afternoon, I met painter Salman Toor in his Bushwick studio to discuss art, Queerness, life, and whatever else might emerge from our conversation. Salman and I have been friends for a while; this was my second time visiting his sanctuary. The first was nearly one year prior, when I attended a small party to celebrate his return to New York after a lengthy time in Pakistan. But that was a nighttime affair. In the day, despite the brume, light softly infused Toor’s workspace thanks to perpendicular walls with banks of large windows; a few miles away, the Manhattan skyline rose in sharp relief. Nearer to us, city sounds were constant: train clatter, delivery truck squeal, someone using a circular saw.

Born in Pakistan, Toor has been largely based in New York City since 1999. His work is in high demand. In a recent profile in The New Yorker, Calvin Tomkins wrote that Toor “could paint anything and make me believe in it,” which seems, to me, praise in its highest form. In 2020, Toor showed fifteen works in a solo presentation entitled How Will I Know at the Whitney; another museum show, No Ordinary Love, was on view at the Baltimore Museum of Art through late October 2022. Having just shipped a great number of works to M Woods in Beijing for yet another institutional exhibition, his studio wasn’t empty, but was clearly in a liminal state between happenings.

After talking for several hours, we shopped at the bodega across the street for tonic water and bags of ice, and the evening concluded in an intimate gathering with a few other art-world Queers. We shared hot pizza, cold Kylie Minogue branded champagne, elegant Swedish gummy candies, and searched for a tiny, shy, darling mouse who, thanks to a door left slightly ajar, insisted on crashing our party in its waning moments.

—John Brooks

October 24, 2022

John Brooks: Thank you so much for agreeing to talk with me, Salman.

Salman Toor: Of course! Welcome.

JB: Let’s start with Queerness. For much of my early life, my own Queerness was a source of fear, and something I sometimes wished to be free of. Rather than being a burden, now it is an essential part of my self and my work. I can’t imagine life without it. Does this resonate with you?

ST: There was a lot of suffering and some very dark, emotional periods in my life, but I found friends at an early age. I never wanted to rid myself of my Queerness, because I couldn’t really see another self. I could never act straight. [laughing]

JB: I understand. [laughing]

ST: I tried. I remember I had a friend in school who said, “Ok, let’s try to walk like boys.” [laughing] It was very difficult, and so tiresome, so I stopped.

JB: It is exhausting, spending all of that effort to be someone else.

ST: Yes, it is. All of that effort. And then, conversely, when I did walk like myself, there was a lot of effort needed to not be so self-conscious because I was being watched or cat-called or laughed at. Even when I was in school, there were definitely points when I decided to own it, and just let go of it, where I said, “Fuck it. Ok, fine, this is me, say whatever you want.”

JB: How old were you then?

ST: Fourteen, fifteen. I had nothing to lose. I had a bunch of very good friends with whom I’d become so close.

JB: In your art room…

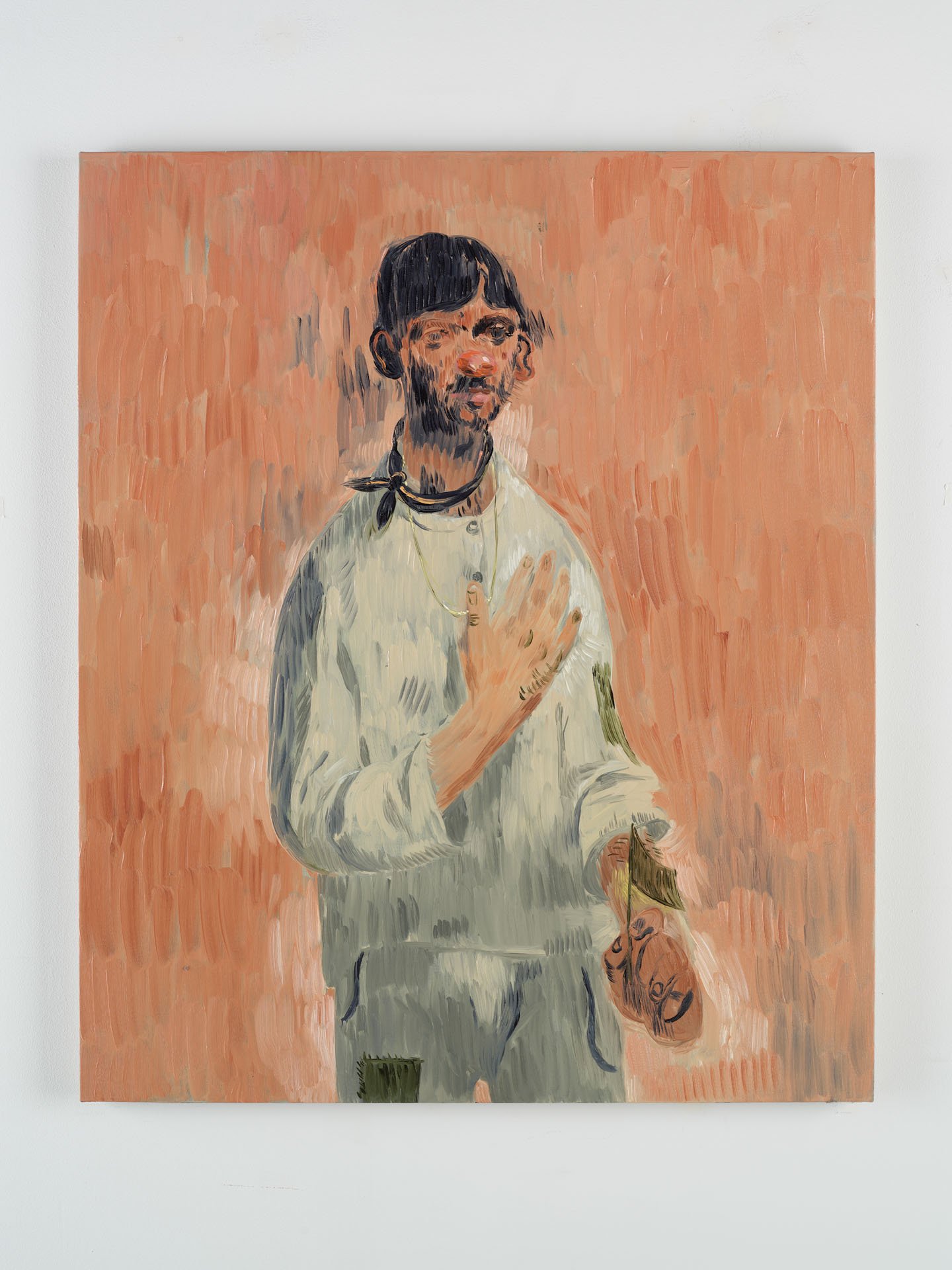

Salman Toor

Lifter, 2022

Oil on linen

20 x 16 inches

© Salman Toor; Courtesy of the artist and Luhring Augustine, New York.

ST: Yes, in the art room. And working for me, in kind of a Queer way, was that in the popular imagination, an artist—especially a figurative painter—was always a male who painted women and there was a certain tragic, poetic heroism in that. I drew women not for that reason at all. I was really into Beyoncé and All Saints and just making all these drawings of cool girls. Weirdly, I think that ended up getting me some respect in school, and that confused people because they had to reconsider being derogatory toward me and actually engage with me on a very different level. People had to choose between two clichés, and that was confusing. In the traditional Pakistani social system, both the path of the artist and that of the homosexual were seen as having tragic ends. As a Queer, femme man, the expectation was that you would either disappear or you would compromise, and get settled, which means that you’d have an outer face of conformity. It was an unsaid expectation perpetuated by adults and other teenagers.

JB: When you say disappear, do you mean something happening like being killed or moving away or simply vanishing from public life?

ST: One would be expected to disappear from view, because in order to live the kind of life you wanted, to have the kind of fun that you wanted, it was just too dark.

JB: That resonates so much with my own experiences and early understandings of Queer existence. How old are you?

ST: Thirty-nine.

JB: Right. I’m forty-four, so we are roughly the same age, certainly the same generation. Even though we grew up in very different places—central Kentucky in my case and Lahore in yours—we were shaped by similar experiences. I came out when I was in college, but even after I had been out for a while, I was constantly advised to live my gay life—my romantic, sexual life—somewhere else other than my hometown.

ST: Like, don’t spoil our space.

JB: Exactly.

ST: This is ours, not yours.

JB: I came out to my parents in 1997, when I was nineteen. They were supportive right from the beginning, if a bit bewildered. My mother cried—I remember her saying that she was just so worried about me, worried about the kind of life I’d have. She said I don’t want you to be lonely and unhappy, as if that was the only thing available to gay people. Her intentions were genuine and kind—that’s what she knew. But these expectations and stereotypes are present in so many different cultures because of what those dominant cultures put on us.

ST: Yes.

JB: It’s not like we are necessarily inherently lonely—okay, maybe I am lonely, but all kinds of people are lonely! Queerness doesn’t necessarily dictate loneliness, but it is the dominant culture that makes an outcome such as that more likely. But somehow they want to make out that it’s our problem.

ST: Completely. What I think is being disregarded in those conversations is that that is the collective will of the culture, to make it like that.

JB: Yes.

ST: There is a system of silence. Especially in communities where homosexuality is illegal, silence is encouraged; it is a way of avoiding direct conflict. It’s a kind of violence done to the person who is supposed to be quiet because the intention is you will just quietly lie down and die, on the inside.

JB: Right. As long as you’re not actually yourself, we can deal with you.

ST: It makes me remember this line from “Death Becomes Her”—

JB: Oh, my god, I love your references. [laughing]

ST: [laughing] Yes—it’s Meryl Streep’s character, she says to her husband, “Could you not… breathe?” [laughing] That’s the equivalent of that expectation around Queerness and traditional society.

JB: I find it incredible to be in a position where a part of me that for so long—certainly for all of my youth—hung over me like a dark cloud is now something that I can use in a positive way, and really engage with in my personal and professional life. And also, it’s fun! I’ve discovered there is so much pleasure in my Queerness, though that has taken me a long time to understand, for a number of reasons. I’ve had gay friends since college, but part of me always held back. I have been working as an artist for almost twenty years, and it has really only been within the last few years that I feel like I am fully engaging with contemporary art and am connected to colleagues, peers, and a wider conversation. So much of that engagement and connection is centered around Queerness. The younger me could never have imagined that this was possible. It still surprises me.

ST: For sure. That happened a bit later for me, too. I always had a small circle of friends, but as an adult I understand that I live between cultures, having left my original culture. I don’t see myself becoming completely enmeshed in the American fabric either. I enjoy hovering in the middle, but the most important thing for me while doing that is to have a community—particularly one based around fundamental principles—just as my parents enjoy theirs in a very traditional way. Weirdly, their community is based not only around a traditional outlook, but also around things that they fight against. I think those things that they don’t want or like really bring them together.

John Brooks

John, I’m Only Dancing, 2022

Graphite, colored pencil, pastel on paper

50 x 38.5 inches

JB: Yes, people love a villain, somewhere to place blame. All the more reason we need to keep strengthening our community.

ST: Community has been a major source of comfort for me. It is powerful to be connected with other Queer people, through a Queer network, across cities and state lines, because so many of us are going through similar things. Even though gay culture now seems a lot more mainstream, it can be very lonely if you’re without community, without being in touch with rites of passage that haven’t been canonized enough in the culture for us to expect them, and for us to be rewarded for them, to be celebrated for them. We celebrate each other, and it’s such a feeling of lightness, to know that there are other people going through the same thing, because I do feel that there is a dark, creeping, gift from my parents and their culture, which is that I can sometimes feel that I am without community. I have to fight feeling that something isn’t right.

JB: With you?

ST: It’s just anxiety. It’s fascinating to step into the shoes of a non-Queer heterosexual person, and to inhabit their entitlement. For hundreds of years, they have been represented through the ancient world; through changes of empires, religions, those kinds of fundamental things remain the same and remain represented. They see themselves. Those are such powerful positions that are embedded in peoples’ imaginations, it just shows you that we in the Queer community have a lot of work to do to develop that comfort, to create that sense of entitlement that the others have. We don’t actually have that yet. I feel like it’s very exciting that it’s bubbling up now.

JB: Even though things are inordinately better than they used to be—especially in a place like New York—we are still neither the dominant force in the culture nor the majority, so we are still fighting for representation, let alone equality. I think those experiences as a young person, where every single thing that you do—your very existence—is called into question by almost everyone you encounter—never leave you.

ST: Oh, yeah, that’s what all the poetry and inspiration—and a lot of darkness—comes from. It’s really interesting to create ties between parts of my original culture that I’ve brought with me and kept—parts that I like, parts that are very agreeable and beautiful—with the hard lessons learned by the post-AIDS generation, the battles they fought, centered in this city. I am trying to suture these things, trying to find ways to connect them.

JB: In a 2021 interview with Cassie Packard in BOMB, you were quoted as saying “I see myself as part of a multi-ethnic generation of painters in the US who are taking on art history to update, critique, and tweak it, and to write ourselves into its rich history.” You’re bringing attention to things that you want to bring attention to, adding to them, suturing them together in order to create something new, something that feels expansive.That feels so important, but it takes courage. How did you figure out you were allowed to do that?

ST: I think it takes a sense of not just entitlement, but also love and commitment. The historical images associated with the region where I am from is the Persianate School of painting, Indian miniatures—that whole miniature painting school. In my early art education I was interested in that and still love looking at it, but I didn’t feel that I wasn’t entitled to choose anything from Western art history, if you will. I am just really glad that I can—that I am allowed to do that, or that I got away with it. [laughing] I enjoy crushing the expectation that I should have brought something from my culture over here to, say, entertain Americans—fuck that. [laughing]

JB: I love that, good for you. [laughing] That’s staying in the discussion, by the way.

ST: I’m going to do the taking. [laughing] And hopefully give something back, too.

JB: It is that kind of bold attitude—No, no, I’m not going to do what I am supposed to do or what you want me to do, I am going to do what I want to do—that ultimately ends up creating something more substantial, and that is evident in your work.

ST: Yes, I was very lucky. Maybe it doesn’t work out for everyone in the same way. I never really expected to have any level of real success. Some success did come my way, and I feel like only now am I really processing it. I have just been really, really busy.

JB: Despite the pandemic, it has been a busy couple of years for you.

ST: I didn’t have a moment to stop and look back—I just kept running. Now I’ve had a pause—and I feel like I am really doing it—and I’m completely happy.

JB: Wonderful.

ST: What about you—when did you start painting?

JB: As a kid, I was always put into the “artist” category. I took a few art classes in college.

ST: Did you always have long hair? You have an artiste look.

JB: No, not at all. But my path to becoming an artist for real and my long hair did first happen at the same time. [laughing]

ST: Really?

JB: I always had very short hair—you know I was a golfer. That was a huge part of my early life.

ST: When did you start playing golf?

JB: I suppose I first began playing casually when I was about five or six. My dad was a Parks and Recreation Director, so I was encouraged—never forced—to play all kinds of sports as a kid. I hated every one of them. I was petrified of all these other boys, and the whole team aspect, and all the yelling. It was horrible. [laughing] When I was ten, my dad made me compete in a junior tournament at our local municipal golf course. I was so shy—I wouldn’t even order my own food at a restaurant—and I absolutely did not want to play in this tournament, but I did it. I won my age group by quite a lot, and there was some fanfare, and I could tell people were looking at me differently. So then I thought “Oh, this is kind of fun,” and started playing a lot more. I liked that I could be outside, looking at birds and clouds, and it was an individual sport. And I was very good at it. I worked very hard. It became my life, really. But I always had short hair. [laughing]

ST: And art?

JB: I was always seen as an “artist,” and felt like one at heart, but it was never real to me in the sense of being something I could imagine as a career or even studying. In my childhood home, we had some prints by a regional landscape artist, so there was an awareness of art, but it was peripheral. We never went to any art museums, not that I can remember. I had a kids’ book about Picasso, but being an artist was always out of reach; it was far away, for other people. I went to college on a golf scholarship, but also submitted an art portfolio in an attempt to get a partial art scholarship. It was rejected, and looking back, I can understand why. [laughing] It wasn’t until moving to London when I was twenty-seven that I really started thinking comprehensively about art. I had made paintings here and there but I had no idea what I was doing and the works were so few and far between that it wasn’t like I had anything to show. But my partner Erik’s career took us to London in 2005. I had a work permit, and applied for some jobs—

ST: What were they?

Salman Toor

Pillow Fight, 2022

Oil on linen

24 x 30 inches

© Salman Toor; Courtesy of the artist and Luhring Augustine, New York.

JB: I don’t really remember. I didn’t get any of them! Up to that point I had been focusing on becoming a professional golfer, and supplementing that dream with regular jobs in retail or civil service. But when we moved to London, it was clear to me that the golf path was over. I had no idea what I wanted to do, but after not getting any of those unmemorable jobs, I just started doing what I felt like.

ST: Which was what?

JB: Going to museums and galleries. It was some kind of instinct.

ST: But you hadn’t been to many museums or galleries before that?

JB: No. Erik and I met in 2002, and we had traveled to Europe a couple of times before moving to London, but I had not really traveled that much in the US, and hadn’t visited many museums.

ST: What was the first museum you visited?

Salman Toor

Fag Puddle with Handkerchief and Candle, 2022

Oil on wood panel

24 x 36 inches

© Salman Toor; Courtesy of the artist and Luhring Augustine, New York.

JB: The first art museum I can remember going to was The Prado, in 2001, when I was on a two month backpacking trip visiting friends in various cities after graduating college.

ST: Oh, my God.

JB: Yes, The Prado was quite a place to start.

ST: It’s almost a bit too much.

JB: I was twenty-three. I haven’t been back since, sadly, but I do think that visit was a catalyst for what came later in London. When I started exploring, I was amazed that there was just so much to see and experience. Much of it is free, too. Erik had an American co-worker whose wife was an artist and a new Londoner like me. Luckily, we really liked each other, and she and I saw everything we could. I felt compelled to start making work again, and also decided to start a painting course at Central St. Martins. I took several courses there and a few at other schools in London. And that was the beginning.

ST: When you think about those early visits to museums such as The Prado or The National Gallery in London, were there any paintings that stayed with you?

JB: From The Prado, [Diego Velázquez’] Las Meninas, of course, which is such an easy answer, but there’s a reason that it is. It’s just spectacular.

ST: Of course!

JB: I have always been interested in traveling, and history, and other places, and other stories, and in the poetic, and the romantic, and all of those things are present in painting—especially in a painting like Las Meninas. In The Prado or The National Gallery or Tate Modern, even the space creates an atmosphere of grandeur and gives room to reflect on the scale of time. All of this was new to me, and wondrous.

ST: Yes.

JB: Goya’s El Perro also stuck with me.

ST: Oh, yes. There’s so much empty space in that painting.

JB: It feels existential.

ST: I think it was the critic Robert Hughes who said it was like a picture of a human being looking for God.

JB: Absolutely.

ST: But there’s nothing there. It’s like us looking at the universe in a scientific way—it’s exciting, but we’re also just specks. There’s so much nothing.

JB: Yes. That resonates with me so much. I grew up Catholic, and as a kid, I was a fervent believer. I came to realize that what I was enamored with was the majesty of everything—the robes, the incense, the music, and the architecture, but that the dogma was an anathema to me.

ST: You enjoyed the ritual.

JB: Totally.

ST: Did you wear any costumes?

JB: Yes, I was an altar boy, so we wore red cassocks, or whatever they were called. I loved everything about it.

ST: I’m trying to imagine you in this outfit. [laughing]

JB: Somewhere I have a picture, I can show you later. [laughing] I went to Catholic school for nine years. I was one of the boys targeted for the priesthood. I was a good kid, a polite kid, a serious kid. I got invited to the Bishop’s house for dinner, and things like this. I remember we were once served tomato aspic.

ST: So there was an expectation that you might become a priest?

JB: Yes, but at some point I realized that I didn’t believe any of it—nothing, none of these beliefs that were the tenets of the religion. But I still was drawn to that sense of majesty and reverence for the unknown and the unspeakable and the intangible. That’s all present in art. I think it is particularly present in painting.

ST: Right.

JB: Another painting I became obsessed with was a Botticelli at The National Gallery in London called Portrait of a Young Man.

ST: Oh yes, I know it.

JB: It’s a tiny little painting, but it’s devastating.

ST: He’s also beautiful.

JB: He is beautiful…

ST: That helps! [laughing]

JB: It does. It certainly caught my attention. [laughing] But there is presence. When you look at the painting, you feel a person. For me, it was a profound experience and a meaningful connection.

ST: That is amazing. I also like that generation of painters because they have historical subject matter, which is ancient and mythical, but they hadn’t taken on the ideal kind of faces and bodies from the sculptures, so the people are actually quite different looking. They’re real. They’re not like, for example, the figures in Titians, who turn into these sort of half-sculptural goddesses and god-people.

JB: Yes—the boy in the Botticelli is a real person. There’s something in the bone structure of his face that is imperfect, in terms of symmetry, which makes him feel so real to me.

ST: And he has those piercing eyes. It’s a really intense little portrait.

JB: I’ve spent a lot of time gazing at it, and I must have collected about ten postcards of him. [laughing] I went back last October for the first time in about six years, so I got to say hi again. I can’t escape him.

ST: I’m not usually a Botticelli fan, but I do love his portraits. He’s more of a drawing person for me rather than a painter.

JB: I don’t really look at his work a lot. Actually, historical Italian painting isn’t something I’m deeply interested in—with some exceptions, Caravaggio, for one—I am more interested in Spanish, German, Dutch, and Flemish—

ST: Flemish!

JB: Yes! But I do love that little Botticelli portrait.

ST: It feels very contemporary. He looks like a model.

JB: Yeah. [laughing]

ST: It’s fascinating how these first impressions remain with you forever. I had a picture stuck in my head, which I had seen the first time I went to a big museum, which was The National Gallery in London. It is a painting from the late 19th century; weirdly there was a taste among French painters for doing English renaissance themes—so, French painters doing paintings of executions and coronations of Tudors. The painting is called The Execution of Lady Jane Grey by Paul Delaroche. It’s not really a painterly painting; it’s very realistic, and he got some of the costumes wrong, but this was the first Western painting that I’d seen like this, and it had been recently cleaned, I think—it also wasn’t that old—it was polished, varnished, and the whole CGI, theater element of the scene really struck me.

JB: How old were you?

John Brooks

Mind Over Matter is Magic, 2021

Oil on canvas

56 x 46 inches

ST: I was young, probably sixteen or seventeen. I had no idea about the Tudors, or British history at all, it has only been recently that I’ve gotten really into reading about the end of the Plantagenets and the beginning of the Tudors and the Stewarts. But this Delaroche painting really struck me. There is this kind of cheap and vulgar excitement in the painting, where this extremely pale, extremely soft looking young girl is going to be chopped up.

JB: It’s historical torture porn.

ST: Yeah.

JB: But in a safe, dignified form, like you’re allowed to look at this because it’s grand.

ST: It looks like it is taken straight out of the world of theater. Audiences would recognize this kind of thing as like a scene from a play. Even though I’m not a huge Delaroche fan, I think there was something in this painting—

JB: The light is incredible.

ST: The light is incredible. This was a dark, nineteenth century time, and he also did a painting of the two young boy princes—Edward V and the Duke of York—who were imprisoned in the tower of London and later murdered by Richard III. I don’t know why he was doing these, but there was something in it for me, something to do with binaries and gender, and gender relationships, and a kind of dark excitement of art. I took that back with me to Pakistan, a place which has its own kind of strange, poetic, toxic complications. But this was something Western, something new to me. I wanted to think about it and explore it more by looking at more pictures.

JB: But you were also thinking about technique.

ST: Yes. I was very impressed by how finished it was. I have to say, this isn’t a painting that I would necessarily admire today. If I were to see it again, I wouldn’t look at it too long. It’s too finished.

JB: It is so perfect.

ST: And it’s almost life size. It’s a huge painting. But at the time it mattered to me how realistically a painting was finished, and I was very impressed. I thought, Wow, if I could paint like that…but I also felt that was nearly impossible, like I can’t do that, like how would I know all of these things? The painting is so full of light, there are all these subtle angles of the body, and how would I learn all of this? But it was a lesson, not only in sort of gender relations, and fashion, but also like a cosmetic experience. I wanted to know how is this made, how are these aesthetics conspiring to make us feel a certain way.

JB: Feeling is always what I’m most interested in. I care about other aspects—technique, aesthetics, composition, of course—but feeling is still my primary response. In the past, I sometimes never even got to concerns about technique. But there was one painting at the National Gallery that, in terms of technique, did astonish me the first time I saw it: The Ambassadors—

ST: Holbein.

JB: Yes, oh my god.

ST: Yes, that painting is so finished. I don’t even understand how it came to be. It’s so precious, like a jewel.

JB: A very big jewel!

ST: Yes!

JB: With those two very big dudes, with shoulders that are like five feet wide. [laughing]

ST: Yes. And the skull is incredible, too.

JB: Yes.

ST: That skull also shows you that the painter is a kind of magician—especially then—making images in a world where people didn’t have Instagram, where there was no photography. It is really finished, really refined, but it also has thrills in it, thrills that today might be considered quite cheap—this skull from a rakish angle. The painting is for an elite class of people, but I like that within that, there is a lot of playfulness. On the one hand it is talking about death, but it also wants to amuse and scare.

JB: I love your use of the word magician; there’s a flourish, sort of a voila, look what I did.

ST: Yeah, be amazed by what I can do. I think it’s very cool.

JB: I love that juxtaposition of things that are both serious and playful. It makes me think of Beckmann, who is so important to me. There is much in his work that is so dark and heady, but there are also things that are very funny, and peculiar, and grotesque, and salacious.

ST: There is also a lot of playfulness in his bright colors. There are a lot of candy colors in your work. Was it always like that?

JB: Definitely not, though my earliest London paintings were colorful. I suppose there has been a bit of back and forth in that regard—I am thinking of some paintings from around 2010 that were gestural, with a lot of whites—but in 2018 there was a huge aesthetic shift in my work. It’s a long story, but I had reached a point with painting where I didn’t know what to do and decided I was going to quit. I worked through those feelings because I like working with oil paint so much. I knew I had to figure it out, and came to understand that my problem was one of composition; it wasn’t necessarily that I was beginning a painting without a plan, but there was an element of that attitude and it wasn’t working for me. I had a collage practice and a poetry practice—neither of which were integrated with my painting practice—and I began using the collages as a basis for composition for the paintings and, in some cases, there was some text from poems on the works, although ultimately I painted over all of that. The poetic text became the titles, and there were poems corresponding to the paintings—sometimes the poem came first and then the painting, and sometimes the opposite.

ST: Oh, that’s interesting.

JB: In those first “new” paintings in 2018/2019, the color palette was very limited, very spare. There were a lot of whites, a lot of almost-whites, and some bare gessoed canvas, all of which was all a nod to the poetry. With poetry, I write and then work to get rid of much of what I’ve written, winnowing them down to the slimmest way they can say what I want them to say. It becomes very clean. I wanted the paintings to reflect that, so I kept the color palette really limited. And then, after making those paintings, I found myself wanting to react against those concepts, which resulted in a painting exhibition entitled We All Come and Go Unknown in summer 2021 at Moremen Gallery in Louisville; this was the exhibition Garth Greenwell wrote about in The New Yorker. There was a lot of color in those paintings.

ST: So, the prominence of color was a return.

JB: Yes. The palette—though not the compositions—was similar to the first paintings I made in London, around 2006. And at that time I was looking at a lot of Beckmann, Doig—

ST: Warhol?

John Brooks: Thinking About Danger at Luis De Jesus Los Angeles, 2022

JB: No, not Warhol at that time. Marlene Dumas, Hockney. Then for some reason I had moved away from thinking about those influences. When I started that body of work in 2021, color was a conscious choice. I do love Kirchner, and he uses a lot of these kooky colors—and I look at him a lot.

ST: His colors are almost like stained glass, with a lot of black.

JB: Yes. I think a lot of the colors, or even my sense of color, comes from thinking about him. I finished, I think, twenty-five paintings for that exhibition last year, and while I made every choice for every color, they were, somehow, subconscious choices. But so much of the feedback from the show was about the saturated color, which made me look at the work through a different lens.

ST: Interesting.

JB: Obviously I was in control of the color—I made the paintings. With the newest paintings, for the exhibition I had this summer with Luis De Jesus Los Angeles, I thought what would happen if I continued doing what I am doing, with regard to concept and source material—the bodies of work from 2021 and 2022 are aligned—but also really consciously thought about color? That distinction is so slight, and maybe it only matters to me, but it’s real. The paintings for L.A. were extremely colorful, and it was a lot of fun.

ST: I love the pop element of your color and how your work features celebrities, but there is something very comforting and almost retro about it, too. I don’t see that a lot in contemporary painting.

JB: Thank you. Do you mean the celebrity aspect or the color?

ST: Both. And I think especially some of the more iconic paintings, the brightest paintings, like Hello, Friend From the Road, with Lil Nas X. It’s like a music video. I love it. It makes me feel fun and empowered.

JB: Oh, thank you! I love that.

ST: It feels like…strutting down the hallway with smoking guns. [laughing] It’s empowering, and has a sense of whimsy, frivolity, fashion, celebrity. I think it has a relationship with fame. Do you think so?

JB: This is new territory for me, in a way, because until fairly recently, my work has had a lot to do with longing and loneliness. The work has changed in the last couple of years, and that has coincided with some self-realization. I have felt pretty isolated for many years, and like I was making work that didn’t matter, was not engaging with anything. That has changed, and I have been able to access more joy, and have more fun. Those aspects of my personality have always existed, but I haven’t really been able to pursue those parts of me.

With very few exceptions, all of the figures in my work are people I know, or have some kind of relationship with or, in the case of the celebrities, someone with whom I feel kinship, for one reason or another. They’re people I’d like to know. For example, I have painted and drawn Marlene Dietrich a number of times, and there are so many reasons I am interested in her. There is indeed something about glamor. I’ve never thought about connecting the two, but both Lil Nas X and Dietrich have these glamorous personas, and I think one of the reasons I admire and am attracted to them is that they both carry themselves with such a sense of fuck everyone else, I’m going to do what I want. For so long, I didn’t live that way, and I find that attitude toward freedom really appealing. Dietrich was wearing men’s tuxedos a century ago, and here we are still having all of these heated discussions about gender identity and gender expressions. Marlene says, why are you still debating this? I already did this. Let’s move on.

ST: Well, those in opposition have a much longer history.

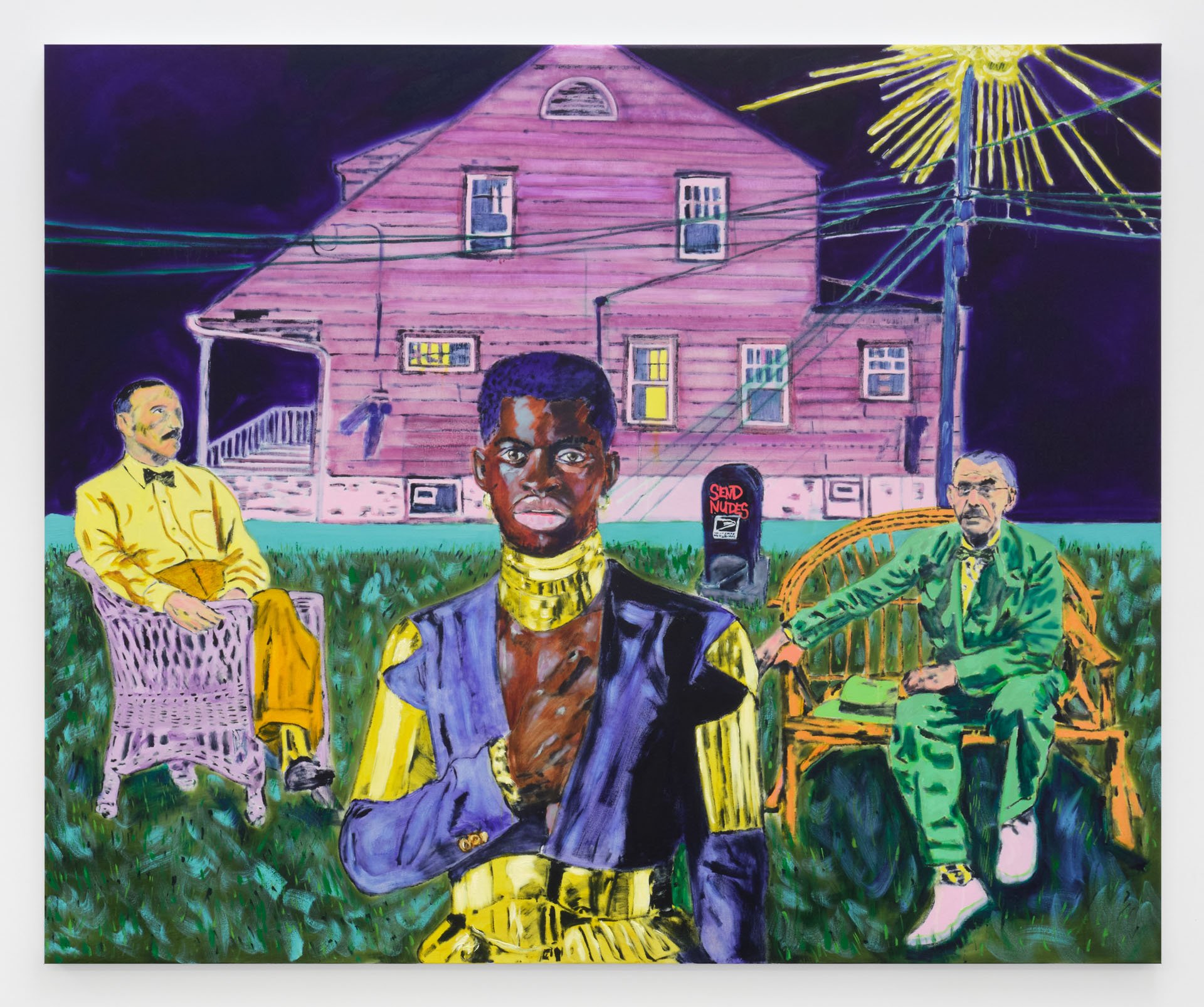

John Brooks

Hello, Friend From the Road, 2022

Oil on canvas

66 x 80 inches

JB: Yes, it’s just as you said before, we are fighting against this long, entrenched history, and tradition. They fight back against every progress we make.

ST: It’s also the case that in the non-Queer world, a lot of the truths and facts about their relationships are so shrouded by religious language and ritual. Whenever the focus is on us—like let’s talk about gay marriage, or young people transitioning, becoming trans—straight people are forced to think of us only in a very sexual way. In reality, what we do is not very different at all from what they do, but they’ve had centuries of visual propaganda to enshrine the sex they have. That visual system has continued through theater, literature, religion, movies, photography, there are huge collections and archives of very mainstream images, and those images are our burden to carry as well, but we are not really their burden at all. They don’t want to think about us. Recently, someone was saying to me that one of the difficult things for the parents of Queer kids is that they are forced to imagine their kids having sex, whereas with their other children they don’t have to as much because it is garbed in tradition and so much magic. And actually what we need is magic as well. We need our own rituals.

JB: Well, we have a lot of magic. [laughing]

ST: We do, and I think that’s one of the things that I appreciate about this kind of painting coming back. There is a new focus on body and identity and that has created a lot of magic in a place where maybe magic was being lost. It has created new mythologies about bodies of all kinds, bodies of color, that are intersectional, about trauma and healing through the body. I think that this is an attempt to create magic around an idea that has been a little forgotten, which is that as a Queer community we actually do need images of ourselves, through photography or painting or whatever, to proliferate in the culture.

JB: Yes.

ST: Even though we live in a time of TikTok and Instagram, I think what makes painting special is that it has a relationship to the language of the elite throughout history.

JB: At the moment, I feel we almost have an advantage as Queer artists. We are operating on more than one plane. We have penetrated the conversation enough to be part of it—whereas historically we weren’t—but we are also still doing this important service and work of building culture for our own marginalized community. Here is where this question, are you a gay artist?, presents itself. To me, the answer is yes and no.

ST: Right.

JB: Obviously, I am a gay person, that is part of my work—intentionally so—but YOU don’t get to put it in that category. If I want to put it in that category, I can, but I don’t even like the question. It implies a yes…but, when really it’s a yes…and. I suppose it depends who’s asking.

ST: Oh, I agree. We should treat the other side the same. Every time there is a new straight rom-com, we should say, Oh there’s a new heterosexual movie out for all of us to consume. [laughing]

JB: Exactly. [laughing] It’s the same old thing of making them the norm, and anything that deviates—

ST: They’re the hosts. It is their party.

JB: Exactly. That’s a beautiful way of putting it.

ST: Speaking of parties, what was it like to be written about by Garth Greenwell? I mean, he’s a Queer god.

JB: He is amazing. It was surprising. I had read some of his work, but I didn’t realize he was originally from Kentucky. When my exhibition opened last summer in Louisville, he DM’d me on Instagram—we had only messaged once or twice before about some obscure 90s music I had posted, Katell Keineg, I think—so we hadn’t really communicated at all. He told me he was planning on coming to the opening, and I was flabbergasted. I had no idea he was around. I met him at the gallery, and we had a long conversation about the work, which he loved. We are the same age and have a lot of the same references, and just understood each other. We then met for coffee, talked more about my practice, and then he proposed writing the piece for The New Yorker.

ST: How cool.

JB: I am grateful for it for many reasons, most of all because I felt so seen. I felt like he understood exactly what I’m doing, why I am doing it, and where it is coming from. As an artist, to have that kind of critique—there is nothing better. And to have it be from someone who is such a beautiful writer and in such a fantastic forum is a dream.

ST: What’s your favorite book of his?

JB: Cleanness, I think.

ST: Me, too! What Belongs to You was also wonderful, and important to me, too.

JB: Yes, me too.

ST: There are one or two extremely pointed scenes—early memories of going to museums or something like that, memories of reading a book—in the book that never left me. That part in What Belongs to You where the protagonist and his lover meet in a McDonald’s restroom, and it’s very close to the kids’ playhouse. The proximity between their seedy sex and the world of families and kids. There was another scene where the protagonist was on a train with his mother and lover and someone else’s child. It was his own expectation, or the expectation of the reader, to feel protective or anxious about that proximity. That book came out in 2016, but those are things I am still thinking about. But I really enjoyed Cleanness as well. It has this sense of the protagonist as like this floating consciousness, moving around.

JB: Exactly. There’s a sense of remoteness.

ST: I felt like he was able to draw me into whatever environment he wanted me in, very seamlessly, without noticing. I think that’s one of the great things a fiction writer can do.

Salman Toor

Man with Flag, 2022

Oil on linen

49 x 41 inches

© Salman Toor; Courtesy of the artist and Luhring Augustine, New York.

JB: It reminded me, in a strange way, of the Swiss writer Robert Walser, whom I love.

Salman Toor

Page from the artist’s sketchbook

© Salman Toor; Courtesy of the artist and Luhring Augustine, New York.

ST: Yes, I know him.

JB: Very different writing, very different subject matter, but a similar slightly floating consciousness.

ST: Yes. Let’s talk about the work you made for your recent exhibition in Los Angeles with Luis De Jesus. The show was called Thinking About Danger. The idea of danger, where did that come from?

JB: Danger is an idea I am still pursuing. The exhibition’s title came from the lyrics of a Marianne Faithfull song called Times Square. I love her. She is held up as this goddess for so many reasons—people love to talk about how she is such a survivor, she was a drug addict, she was homeless—I don’t really care so much about that. I care about her because I believe her when she sings. There are many reasons I am drawn to particular musicians, but I always ask myself—and I think the same is true for how I experience visual artists—do I believe what this person is giving to me? With her, I do. She’s been part of my life for a long time. When I was sixteen—this was 1994—my friend Shannon had an old Volvo, and she and I would drive around listening to music, looking for things to do. There wasn’t much to do in Frankfort at the time, but sometimes we went to Wal-Mart for entertainment. [laughing] On one such night, I rifled through the cassette tape bargain bin, and found this Marianne Faithfull tape—a live album from 1990 called Blazing Away. I don’t know if you had these in Pakistan, but the discount cassette tapes had a notch cut out of the side of the plastic case—I don’t know why…

ST: But you knew it wasn’t new.

JB: Right. This song, Times Square, it really is about her addiction to drugs and alcohol—which, certainly as a sixteen year-old, didn’t register with me—but there was such a sense of desperation that came through in her singing, and in the lyrics. It spoke to me deeply, especially the verse—In a car taking a back seat / Staring out the window / Thinking about danger. / Playing in a wrong world / Fighting—but I’m not free. / Talking on the telephone / Talking about you and me. Somehow I understood that the danger was in me, because of my sexuality, which I was coming to understand at the time. But also due to the fact that I always felt out of place. I had a stable home life, I was safe, and secure and all of that, but I was very, very lonely as a kid and the things I was interested in were always weird to other people and everyone looked at me sort of like where did you come from? [laughing] There was something in me that I felt was inherently wrong, or dangerous even. Dangerous to give in to. I thought a lot about suicide. Something connected to all of that was transmitted in her singing, and it registered with me.

ST: Did you know of her before?

JB: I had heard of her; my dad has a brother who was a world traveler in the late 60s, early 70s. If you listened to the Jimmy Wright TalkArt episode they just released, he talked about traveling from London to India, and my uncle David did that same thing, if not the same route.

ST: On the bike?

JB: I don’t think on a bike, but the same route. I think they actually converted a garbage truck in North Africa or something. But he moved to Australia in 1980, and left all his records with my parents. They liked music, but never really listened to his records, but I discovered this treasure trove when I was like twelve. They were all from the 60s and 70s—so I had heard some Marianne Faithfull, like singing Dylan’s “It’s All Over Now, Baby Blue,” but it was her early, very folky music, with her high, angelic voice. I had also read about her in Rolling Stone, so she was this kind of mythical figure. Then I got this cassette from Wal-Mart, and her voice was so different, so deep and husky and weathered, I thought ok what happened between then and now? She was a beacon for me, in a way, a reminder, making sure I was aware that there was life elsewhere. It was something to latch onto. It wasn’t exactly hope, but somehow it let me know that there was life beyond where I lived. And I was always interested in that. As a kid, my room was plastered with maps from National Geographic. I was always interested in geography, and far-flung places.

ST: I feel similarly. What I picked up from that was something that probably has to do with my own relationship to the world, which was that just growing up in this kind of stifling respectability and knowing that the things I wanted were way outside of that…

JB: Exactly.

ST: So that danger kind of gave a mad thrill sometimes. [laughing] You know—I’m bad. And I like it. [laughing]

JB: Yes. [laughing] I have really only been able to accept and engage with that feeling in the last few years. My Catholic guilt has finally subsided. [laughing]

ST: I think that sense of danger also continues into the culture of cruising, for instance, a kind of reckless behavior that at once fulfills but also takes away at the same time.

JB: Yes, you’re drawn to it and simultaneously repelled by it.

ST: Yes, I really appreciate it when paintings and literature kind of occupy that space, and explore it more. I felt totally seen by Evan Moffitt, an art critic who wrote the book for my show at the Baltimore Museum of Art. When making the work, I wanted there to be nightscapes with wandering figures, maybe having romances or cruising the park, and was working from memories of thinking about those spaces in places like Pakistan, or New York. I wanted to lose that sense of East or West and have it be just some place thrilling.

JB: I was there with you at the opening in Baltimore, and all of that comes through in the work.

ST: The work for the Chinese show has a lot of these night landscapes that have a lot of figures making out.

JB: Oh! [laughing]

ST: It was very enjoyable to do. I was just drawn to making very sensual trees, so the trees are kind of like fags. They’re very twisty, and limpy, and gnarly [laughing] and then the figures inside them are also twisting together, embracing in different ways. They’re not from models or pictures, so I am trying to figure out how bodies can entangle themselves as I’m drawing them. It was fun to paint, but that too, was propelled by the idea of danger. So, when I saw your work, I really connected with that.

JB: Wonderful. That Marianne Faithfull song—and the painting with that title—was the catalyst for the work, but there are various forms and explorations of danger within the other paintings. There is one painting called “You Can’t Shake It or Break It With Your Motown,” which features an image of me juxtaposed with Dr. Caligari from the film “The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari.”

ST: I don’t know that film.

JB: It’s German, silent. 102 years old, I think. I watched it last year, and the basic premise is that there is this mysterious hypnotist, Dr. Caligari—played by Werner Krauss, who would later go on to collaborate with Nazis—who is part of a traveling fair. He comes to town and mesmerizes the citizenry by putting people to sleep, but he is also using these powers to get a hypnotized man—they call him the somnambulist, “the sleep walker”—to commit murder for him. But then…some things happen and you wonder if any of it is real—

ST: Oh, I see.

JB: When I watched it, it felt so relevant, so contemporary. A couple of years ago, someone had described to me that the reality of living under Trump or in the era of Trumpism is that it is as if we are living in a medieval fairy tale and half the village has been put under the spell of an evil sorcerer. That made so much sense to me.

ST: Oh, yes.

JB: When I saw Dr. Caligari, I saw Trump. I felt like this is what’s happening now. Using Caligari film stills, I made a couple of paintings in 2021, which were part of the exhibition at Moremen Gallery. I think the story and the visuals are just so apt, and I love it. Dr. Caligari also resembles David Hockney a bit. [laughing] There’s a doubleness there, too. There is another painting with Sal Mineo, who was in love with James Dean in Rebel Without a Cause, and maybe in real life—

ST: Were they together officially?

JB: No, not really. I don’t think so. But there was something there. The chemistry and lust is undeniable on screen. Sal went on to have a movie career, but he was stabbed to death in West Hollywood in 1976.

ST: Oh, no.

JB: In my painting there is also an image, borrowed from a Fritz Lang film called Scarlet Street, of a sharp knife and the legs and feet of a character played by Edward G. Robinson, whom I adore. So there are all sorts of ideas related to danger in the work. And I think the juxtaposition of the bright colors, which don’t necessarily go with—

John Brooks

La Ritournelle, 2022

Graphite, colored pencil, pastel on paper

50 x 38.5 inches

ST: Those black and white films.

JB: Right, and the general mood.

ST: There must be a sense of theater and camp. I definitely read the camp in the paintings.

JB: Yes, and drama. I have been wanting to make paintings like this for a long time—maybe fifteen years—but for whatever reason, I wouldn’t let myself.

ST: Your inner saboteur was winning, as RuPaul would say.

JB: Yes. At some point I stopped listening to that voice, and now feel emboldened to make what I want to make.

ST: Your paintings also reminded me—I went recently to the Lil Nas X tour, and it was so fun! It was so, so, so, so, glamorous and cool, the dancing was out of this world. It was just a different level of comfort with camp and femme and most of all, the audience was just chaos. It was so fun, people from all over the country, and the young people were just dressed up, all these Gen Zs, with their huge platforms—

JB: And they’re all so confident, and happy.

ST: Yes. At least they look it.

JB: Of course. That’s what they’re presenting, which I understand isn’t the case all of the time.

ST: No.

JB: But I am inspired by that. As a kid, I remember seeing Annie Lennox on MTV in the video for Sweet Dreams (Are Made of This), wearing a man’s suit and tie—here we are again, like Dietrich—with that orange hair, and with those cows—I thought what is this, who is that? I want to know these people.

John Brooks: I See this Echoing at MARCH, New York

ST: I really like your sense of camp because I think it’s related to a sense of femmeness or femininity in my own painting as well, and to me that has been the most important part of the development in this culture since I have been here. I have been here for twenty years. In 2006, it was not okay to be femme, just like it has never been okay in Pakistan, either. But now there is a real examination of why we choose to take the straight male view of everything, and why is that easier, why is that encouraged, and why have we felt inherent shame in supporting other femme-presenting people.

JB: It makes some people uncomfortable.

ST: Yeah, I think that it points to a way that they look at women that makes them uncomfortable about their own ideas. This is something I would like to push more with painting and my own kind of dress sense. Recently I have started wearing skirts. I have always wanted to try them, and I think they’re very comfortable, and there is a part of me that feels like I was completely destined to wear the skirt. [laughing] Why didn’t I wear this before? Through a sense of fashion in painting I want to push that more, because what I see in this new generation, in Gen Z, is a new attitude toward these things. Like you said, it’s emboldening, it’s inspiring. We can create change.

JB: Yes, the feeling of freedom to disregard long-established rules.

ST: Yes, and also sensitivity, and presenting vulnerability, finding strength in that.

JB: Yes, I was looking at your work and thinking about vulnerability and emotion. That’s something I value in my own work. That’s how I move through the world—I’m not volatile, in an emotional way—but I relate to things on an emotional level, I see and experience through that lens. For so long I thought, no I can’t put that in the work, or can’t talk about that, because it’s so soft, and people will think it’s not serious. But it’s absolutely necessary for me. And that tenderness is so evident in your work. For me, it’s one of the things that makes it so compelling.

ST: Thank you. I was always attracted to the stories that were supposed to be hidden the most, and personal storytelling. Because repressive cultures depend on you not saying those things.

JB: Yes.

ST: They can’t survive if you’re articulate. I feel like if you’re a painter or writer, you really want to examine those things that have been cast aside. I want to point out that this is the whole picture of the environment that they think they belong to, even if they don’t want to envision it. When picturing growing up, collective memories of family, family homes, environments in South Asia, I want to claim them as a Queer man and have the rest become the background, and to become a protagonist in that story rather than participating on their terms.

JB: We’re the hosts.

ST: Yes, we’re the hosts now. Are you on the list? [laughing] I don’t think you’re on the list. [laughing]

JB: What’s the secret password? [laughing]

ST: I have been meaning to ask you—you have made several paintings featuring Nick Jonas. Why Nick Jonas?

JB: I am still figuring that out. [laughing]

ST: Do you think he’s hot?

JB: Yes, I do. And actually, I do know why I’ve been using him. To me he represents a kind of contemporary, open, heterosexual masculinity. As an actor, he has taken on a number of roles that have been Queer or Queer-adjacent, and he’s an advocate for our community, and from what I have seen he doesn’t seem to feel the need to defend any of that. I think in the past, some actors either wouldn’t have taken such roles or if they did, they’d counteract that with future roles, or make sure that everyone knows they’re super straight, and I just don’t get that sense from him. I know he’s married to Priyanka Chopra, but there’s just something open and easy about how he presents himself.

ST: He’s not toxic, at all.

JB: Yes, and when I was younger, that’s not something I had any sense of being represented anywhere. So he is sort of a stand-in for a lot of younger straight guys whom I have met in my adult life. They’re just relaxed, they’re not so hung up on proving themselves. Relationships and interactions are so much easier now than they were with guys when I was younger.

ST: Yes, although I think a lot of them may have their own complications to solve as time goes by, because we never had trans-visibility like there is now. We never faced those questions. I felt a bit trans in high school. I may have been a very different person if I were Gen Z but then the way that I perceive myself, it is just so malleable. I transformed many times.

JB: When I was a kid I loved dressing up in my grandmother’s clothes: dresses, long necklaces. I can recall the thrill of wearing them. I loved sneaking glimpses of Dynasty and Falcon Crest and Dallas, with these very strong, fancy, often catty women. As a child, a lot of the things I drew were related to women’s fashion. I loved playing with Barbie dolls. I had a friend who was a girl, and she had everything Barbie-related, and I loved going over to her house to play with them. I very vividly remember being twelve years old, and her mother coming to pick me up, and my father saying to me as I waited on the porch—“Ok, you’re twelve years old now, you cannot play with those Barbies anymore.” It was so obvious the adults had been talking about me. I felt so ashamed.

ST: I went through the same thing. It’s like we literally had the same experience. As we have been saying—there are so many shared experiences and they’re so specific. No other community can relate to that. It makes our community so special.

JB: It does. We already know each other, before we’ve met.

ST: It really makes it so much lighter, and funnier, and meaningful, rather than like something that just happened between you and your dad. It makes it an official rite of passage.

JB: I always knew my parents loved me, but outside of the house, I was teased mercilessly as a kid. I was never teacher’s pet, but I was good with adults, and was always interested in pleasing, so that, coupled with my effeminacy, was a bad combination, at least in the eyes of my peers. And I was also very sensitive. I cried a lot at school. And I remember—I think I must have been about ten or eleven—I had devised a plan that the only way for me to get through this, to survive this, was to move to Iceland—

ST: Because…?

JB: I don’t know, perhaps because it was far away and remote and no one knew me.

ST: And all the adults would not make fun of you?

JB: No, I was going to move there and start living as a girl, and then I would come back to Kentucky as a new girl.

ST: Wow. And that would only happen in Iceland. [laughing]

JB: Yes. [laughing] All I knew of Iceland was what I’d seen in National Geographic. This was before Bjork. [laughing] I didn’t actually want to be a girl; it wasn’t that I was confused, but other people—boys, particularly, but also adults—were so adamant that I was girly, so I felt I had to relent, I had to accept their assessment of me. I don’t know how I thought that would actually happen, but I envisioned it.

ST: That is definitely something that rings a bell with me, too.

JB: That’s not a story I thought we’d cover. [laughing] Tell me about your painting process. Do you always begin with a ground? And is it raw umber?

ST: Yes, I prepare a raw umber ground in acrylic, a leftover habit from my academic days. I let that dry, then I paint directly on it, relying on imagination. No references, although I’m thinking of some, I don’t have them physically in front of me. So I have to work out compositional, anatomical stuff in the moment. Sometimes I’ll work from small ball-point preparatory drawings. I keep a little diary of these and tend to finish the drawings so they can be shown in their own context.

JB: Your work has become synonymous with the color green—do you have a particular favorite green paint?

ST: I like to use Hooker’s Green and Phthalo Green as base colors when I’m doing a green painting.

JB: And how much mixing do you do with your colors? In my own work, I love going down the road of altering and inventing colors, seeing what appears.

ST: I can get carried away with mixing, it’s an indulgent, sensual process. I also mix pigments on the surface of the painting, trying to control the paint there. Sometimes that can go south because paint isn’t always fun to control—unlike a drawing, in my experience.

JB: Your figures are invented from your imagination, but often there are inspirations from reality, such as the sexy construction workers in “Construction Men”. Are you often looking for inspiration when you’re out in the world?

ST: I live for it. I got the idea for construction workers because of the constant construction right by my apartment building. I look at everything, trees, faces on the train, street fashion that can translate beautifully into painting. I also keep a mental log of paintings I want to steal from. I’ve been thinking of Balthus’s landscapes and street scenes, Picasso’s beggars, some early Alice Neel, and some late Guston—it’s not possible to ignore him—and lovely 17th century Mughal court paintings I’ve saved in my phone over the years.

JB: Balthus, Neel, Guston, Picasso, and Mughal court paintings—I love the strange bedfellows we all bring together. [laughing]

Salman Toor

Construction Men, 2021

Oil on canvas

60 x 48 inches

© Salman Toor; Courtesy of the artist and Luhring Augustine, New York.

ST: Me, too! [laughing] Tell me about your process.

JB: When the aesthetic shift in my work began four years ago, I was working with physical paper collages as a basis for the composition of the paintings. I have stopped using the paper collages but the mindset is the same, combining things from disparate sources. The first Nick Jonas painting I made last year—entitled “We All Come and Go Unknown,” which is from a Joni Mitchell lyric—felt like something new. Combining an image of Nick Jonas with these two huge golden standard poodles and a background borrowed from a work by Karl Schmidt-Rottluff created a dynamic that felt familiar but not knowable. It couldn’t be pinned down, like it refused to give an answer, which is a feeling I’m always after. When I put those things together I realized that only I would do this: the Venn Diagram of people who are interested in Nick Jonas, poodles, Schmidt-Rottluff and Joni Mitchell—is a pretty small list. So I felt like in doing the thing that only I would do, something new was being created. That feels really powerful. Sometimes I take the photographs that end up in work—but in many cases, I use things that already exist because they come with weight, and I can take that weight and shift it, rework it. On my phone, I have a cache of images I’ve found from various sources—friends, art history, film, the internet. Sometimes I see something and remember something else that’s in my cache, and I think ok these things are meant to go together, for whatever reason, and other times I don’t know what I’ll do with it, but if it’s interesting to me, I keep it, and then just go through them and find what speaks to me. There are an infinite number of possibilities, but as I am considering those possibilities, something concrete will emerge.

ST: And is there usually an urgency with regard to particular images, like this one is cooking, I have to use it now?

JB: Yes, sometimes.

ST: How long is the wait?

JB: It can vary. Like, sometimes it is the case that I found something yesterday and want to use it right away, and in other cases, I have things that I have been meaning to use for two years, and I love those things, or I wouldn’t have saved them, but sometimes it doesn’t happen, because I am waiting for the image that compliments it, and I haven’t seen it yet. But I’ll know it when I see it.

ST: And you work with oil paint.

JB: Yes.

ST: And you work directly on a white surface?

JB: I do. I haven’t used a ground for a long time, but I have been considering it.

ST: Oil or acrylic?

JB: Both. I think part of the reason I haven’t experimented with grounds is because I have just been so busy in the last two years, making so much work, that I haven’t had a lot of downtime or prep time. I just want to get to the real work. Maybe if I had someone to help me do prep work.

ST: I can’t let anyone touch my paintings. I feel like this is a part of my life where I have exercised control, whereas outside was never in my control. And I hate to give up any part of it.

JB: I agree, I can’t imagine anyone doing any part of my work.

ST: If I outsourced it, I just don’t know if I’d trust that the person did things exactly to my specifications. If something went wrong, I feel like I would just whip around! [laughing]

JB: Yes! [laughing]

ST: For me, painting is an antisocial activity. I don’t want to socialize.

JB: I totally agree.

ST: I don’t want to feel angry with someone, or suspicious in any way. It’s a completely self-indulgent activity. But it is probably true for you as well, that you end up thinking about people while you’re painting.

JB: Absolutely.

ST: The painting becomes a way of liking those people.

JB: Yes. I enjoy the solitude of the studio, but because I work with figures, and the people are people I know, or want to know, or people who are important to me, I feel like they’re with me in the studio.

ST: Right.

JB: It’s even more true with the drawings–which I exhibited in the spring at MARCH, in your neighborhood– because they are so direct. I feel like, if I drew you today, you were with me in the studio today. We had a great conversation. [laughing]

ST: Yes, for lack of a better word, it’s almost like praying for someone, or thinking about them, creating a fantasy of them.

JB: Yes.

ST: It’s a much more intense, time-consuming way of liking a picture on Instagram. [laughing]

JB: Yes. Even though I have a lot of existential loneliness—which I don’t want to give up entirely, because I think it’s one of the main driving forces behind my creative impulses—I am much less lonely now, feeling connected to all these people that I am drawing and painting.

ST: That’s what I love about adult life. I have a partner and friends, and I’m not in the single space any more, but I do remember being single in my early twenties, and that could be a bit lonely, being a misfit.

JB: Yes.

ST: When I started participating in gay culture in New York, it was not welcoming, like in the sense that you could go to Chelsea, it was a much more concentrated version of Hell’s Kitchen and it was all muscle guys, and very masc oriented, very musk for masc, masc for musk. [laughing] That was a time of feeling like there was no hope for me, and what’s crazy is that I can see there are some kids from Gen Z who are still going through that. We need to have a new culture, not one with these very specific molds of what kinds of bodies are most desirable. It’s also a youth-obsessed culture.

JB: Yes.

ST: It’s interesting to try to push against that. For that reason I like to go into kind of clownish, grotesque attributes in my painting, which are a way to say fuck you to sexiness—

JB: But they’re still sexy.

ST: They are?

JB: Yes, they can be. And they’re beautiful.

ST: Thank you. I like that, the beauty. I have a complicated relationship with sexiness in paintings. I think that, for me, using sexiness as power in a painting…I don’t know if I want to do that.

JB: Does it feel a bit like cheating or a shortcut to you?

ST: Yeah, I think so.

JB: Ok, let’s not call your paintings sexy. [laughing]

ST: Ok. [laughing]

JB: Speaking of sexy, we both happened to be in Venice last month—I was there on a grant to see the Biennale and you, along with your partner Ali (Sethi), were there for a residency. We had dinner together, and Ali asked if I thought Venice was a sexy city.

ST: Yes, I remember.

JB: The answer, of course, is no.

ST: Right.

JB: It’s beautiful and romantic, but not sexy. For me, it’s too immutable to be sexy.

ST: We were also there at a very touristed time. It can feel very Disneyfied, and there’s something very sad about those men playing all those pop songs on the accordion, and all the newlyweds hanging about. There is a sense of oppressive aging. For me, Venice is simply about art.

JB: Me, too. And architecture.

ST: It is about the paintings and the basilicas. Unfortunately, I missed the Biennale. I had a tight schedule and hoped to see things on a Monday, but it was all closed.

JB: You missed out. The Kiefer and the Dumas were incredible, and many of the pavilions.

ST: I did go to Museo Correr, which was very cool.

JB: Yes, I did, too.

ST: A lot of artists I didn’t know about, but beautiful, beautiful work. How did the attitude toward your work change after it was reviewed prominently? Did that reveal to you anything about this industry?

JB: It’s all still a mystery. [laughing] But any artist is lucky to have a champion, because many people, for various reasons, are unwilling to form their own opinions.

John Brooks

You Can't Shake It or Break It With Your Motown, 2022

Oil on canvas

58 x 46 inches

ST: Yes.

JB: As I have to come to more explicitly embrace Queer culture, I’ve seen how my work has grown.

ST: I love how the culture is teaching a new generation to look at Queer culture in a whole different way. It’s kind of giving power back, although power never comes without a little bit of abuse. [laughing] We can feel that developing in the culture, like what is and isn’t ok to say. There’s a whole new set of rules being made. Which is all very exciting.

JB: Yes.

ST: And that’s kind of a sign of accepting power, and wielding it, and that’s what that means. To have a space in the culture is to take responsibility for a portion of it, and to take the helm. It’s your subject population, in a way, to help create the rules.

JB: Yes, and in whatever way I am connected to that creation and formation, I am very grateful, because for so long I have been in the desert. Like…nothing. I know I have something to contribute, and something to say. I know I am building a substantive body of work.

ST: I think so, too. Your work from L.A. looked incredible.

JB: Thank you.

ST: What you said about being in the desert is true, too, from a Queer point of view in South Asia as well, and I kind of relate that to middle America; it’s just another kind of space which is very similar to an environment in which I grew up. In New York City we create small bastions where we hope to have absolute safety. For instance, I haven’t moved to a new neighborhood in seven years. I have stayed in the East Village, because I feel safe wearing a skirt there, in midday, walking, with a skirt billowing in the wind, and going to the post office and putting something in the mail. [laughing] Or even at night, coming back home. That’s my barometer—I’m thinking, can I wear the billowing skirt here? And if I can’t, then I don’t want to move there.

JB: Yes.

ST: And right now I’m thinking about moving. I feel like in Fort Greene, I’ll be required to wear the skirt all the time, so maybe not. [laughing] If I wear it once, I think the very progressive residents will be disappointed if I don’t wear it again. [laughing]

JB: That’s true—you’ve set expectations. [laughing]

ST: Oh, you’re not wearing the skirt. [laughing]

JB: Oh, we thought you were a skirt person. [laughing]

ST: Fort Greene might be way too cool for me. I am looking in Bushwick or the edge of Williamsburg. But they’re very small spaces. I’m so grateful that we have these freedoms but we can’t take them for granted.

JB: Absolutely not.

ST: And they can just be ripped apart so suddenly. I have traveled thousands of miles from Pakistan, have built a life and a home here, built a community which is like a chosen family, far away from my blood family, and my blood tribe, if you want to think of it like that, so I feel invested in this culture from that point of view, in fighting for this corner of it and as fiercely as I can and as we can.

JB: Anything can be taken at any time.

ST: Yeah.

JB: There are people who would absolutely take away our freedoms if they got an opportunity. And they’re trying.

ST: Yes they are.

JB: Yes, Louisville is a fairly liberal city, but it’s not absolute, and Kentucky is certainly a conservative state.

ST: Yeah.

JB: It’s not just that we don’t want to do what they want us to do, it’s more proactive than that. We want to live this way, we want to be free. We must all vigorously defend our freedom and our values.

ST: Right.

JB: We want to be able to wear the skirt to the post office. What does it matter to you? I don’t care what you wear to the post office. [laughing]

ST: Yes, that and thinking about a more basic culture in which anyone who walks and talks like me is thought of only in terms of buggery.

JB: To be reduced only to that.

ST: Yeah, like what do you do in your married life?

JB: Yes.

ST: There are just all these powerful images, coming back to painting, that protect the other side and ironically, we actually like those images, we appreciate the history, being Queer or not, being painters, looking at the history of art. Those are the things that work really well for conservatives.

JB: Give me an example.

ST: I am talking about the powerful rituals, the sacraments, the pie in the sky Palace of Justice . [laughing]

JB: Of course. [laughing]

ST: Justice in the sky, waiting for you. Religious painting. Images of power, images of male power, hero worship, there are so many fewer images in art history that are about androgyny, fewer even that are not jokey—even the Romans made sculptural jokes about hermaphrodites—expecting one thing at the back, getting another thing at the front—or like Renaissance or Baroque painting, boys, or women in roles of power. Those are iconic paintings to us because they dare to look at something other than dick worship.

JB: I’ve had a lot of conversations in the last couple of years about the fact that there are so many men in my work—in the drawings, particularly. There are a lot of comments about all of the dicks. I feel like people aren’t looking at everything or they aren’t aware of the full body of work. Because I have done over one hundred of these new drawings, and there are maybe like thirty dicks—

ST: That’s not very many! [laughing]

JB: I agree! [laughing]

ST: It’s just thirty percent. [laughing]

JB: And I know that before beginning this body of work, I hadn’t drawn a dick in a decade. And other people don’t know that also in my work from a decade ago, there were tons of women because I was at an age when so many of my friends were getting pregnant, so I did all of these weird drawings with Japanese gel pens of pregnant and changing bodies.

ST: Right.

JB: I am still learning how to be a man, and figuring out what that means to me, so that’s part of the work. It’s part of why I am doing this.

ST: I similarly question myself about this one painting in the Baltimore show, this seated boy, he was naked before…

JB: With one shoe off.

Salman Toor

The Kissers, 2022

Charcoal and ink on paper

12 1/8 x 16 inches

© Salman Toor; Courtesy of the artist and Luhring Augustine, New York.

ST: Yes. When he was naked, the painting wasn’t working, and I didn’t like the painting, and when I started it, it was so great and I wasn’t happy when it was finished. In the interim I put up another image on Instagram and someone commented like “oh, one more dick from you,” and that actually made me question what I was doing in the studio. I thought, well, I don’t like this image, why does he have to be naked? So I put some clothes on him and they worked fabulously well—and I was like “thank you, hateful person, I actually took your view for a moment and looked at my work critically and it helped me.”

JB: Which is important to know how and when to do.

ST: Absolutely. I look at my work pretty critically.

JB: I think you have to.

ST: There needs to be enough time to do so, of course, to make the constant changes that come with that kind of critical approach. There are very few paintings that just come together miraculously, that just happen.

JB: Where everything goes right from the beginning.

ST: Yes, and whenever they happen I am just like I can do anything now, I’ve conquered everything. But it’s never the same twice.

JB: I had one of those miraculous paintings making the work for Los Angeles.

ST: Which one was that?

JB: The one with Dr. Caligari. As I was putting it together, I just knew it was right. But I never want to be pinned down in any way, as a human being or as an artist, so I have been doing all of these drawings, which are purposefully very sensual. They’ve felt liberating to me, but I also know that at some point the work will shift, because I want to keep moving forward. There are other things I want to say. I want to keep expanding. At least that’s the plan.

ST: That’s a good plan.

JB: And what’s your plan?

ST: I am kind of discovering what it means to have success, and I am still understanding that. Right now I have no deadlines, I am just making paintings. That seems to work really well for me.

JB: Good.

ST: This is a painting I’m making after a really long time [points to a medium-sized canvas on the wall; three figures, the color coral is prominent]. I feel like I’m back.

JB: I’m so happy for you.

ST: I’m so happy you’re here.

JB: Are you now finished saying things that are profound?

ST: I think so! [laughing]

Artist, poet, and curator John Brooks was born in Frankfort, Kentucky in 1978. He studied Political Science and English literature at the College of Charleston, South Carolina, with continuing education in art at Central St. Martins and the Hampstead School of Art in London, England. His visual work has been exhibited in the United States and Europe and is held in the collections of 21C Museum Hotels, Grinnell College Museum of Art, OZ Arts, The University of Kentucky Medical Center, and numerous private collections; he has been featured in The New Yorker, The Yale Review, Action Spectacle, and Golf Digest. Brooks' poetry has been published in Good River Review, Plainsongs, East by Northeast, and Assaracus, and he has written criticism for Ruckus Journal, UnderMain, and a forthcoming interview for BOMB. From 2017-2022, Brooks operated Quappi Projects, a Louisville-based contemporary art gallery focusing on exhibiting work reflective of the zeitgeist, where he curated over twenty-five exhibitions.

Salman Toor’s sumptuous and insightful figurative paintings depict intimate, quotidian moments in the lives of fictional young, brown, queer men ensconced in contemporary cosmopolitan culture. His work oscillates between heartening and harrowing, seductive and poignant, inviting and eerie.