photographers of color: Aaron Turner, HannaH Price, Sonsoree Gibson, Edward Cushenberry, Emma Uwejoma, and Wendel White

Introduction and curation by Zora J Murff, Essay by Aaron Turner | Published September 1st

I have lived in the Midwest my entire life, and – amongst many other things – growing up in middle America has made me aware of the color of my skin. I lived in predominantly white neighborhoods, received my education in predominantly white classrooms, and had groups of predominantly white friends. Last year I began my MFA track at the University of Nebraska–Lincoln, and the experience of being here has, of course, been no different than my experience of growing up in a place where the population is not very diverse. In the short amount of time I have practiced photography, my artistic emphasis has been on image and identity – how the camera can be used to shape our perceptions of others. In hindsight, this was possibly influenced by constantly thinking about my black skin in the context of a white environment; my color couldn’t be taken out of the equation.

Having slightly shifted my focus from matters of incarceration to matters of race, one question that I continue to hear from colleagues in critiques and studio visits is: “Do you feel that this is work you need to make because you’re black?” The posing of this question, like my experience of the Midwest, always leaves me thinking about the recognition of diversity – or the lack thereof – in the field of photography. Today, photography seems to have to be about something, and to achieve a level of “aboutness” photographs must be packaged cohesively to present a message, argument, or idea. Various images are strung together like the words of a sentence, small parts composing the whole. Much in the same way, photographers who come from different ethnic backgrounds become defined by our color; the pigment of our individual skin groups us. All of us are now small parts of the collective that is “photographers of color”, whether or not we have the desire to be included. Our color has yet to be taken out of the equation.

I first found out about Aaron Turner’s celebration of photographers of color through Twitter in 2014. We stayed in contact digitally, and were finally able to meet in person earlier this year. Although our connection began through digital means, we are tied together through our love for photography, our chosen profession, and our skin color. I believe the continual draw, for me, to what he does is his promotion of photographers of color no matter what type of work they make. In that respect, color is taken out of the equation.

For this week’s feature, Aaron and I collaborated to highlight a few of the photographers who could be considered “photographers of color.” Hannah Price, Edward Cushenberry, Sonseree Gibson, Emma Uwejoma, and Wendel White help us further consider this standard of classification, responding to the question: “What does it mean to you to be a photographer of color?”

"In these times" an essay by Aaron Tuner

When it comes to diversity in photography, one can think about it from so many angles. I recently read an article by John Edwin Mason for Hyperallergic on photographer Louis Draper and his resisting of the label “black photographer,” he felt it would put him in a marginalized position amongst the photo world’s gatekeepers.

“Draper’s photographs won him early acclaim, yet his achievements as a photographer, arts activist, and teacher merit more recognition than they received. He never fully escaped the marginalization that the label “black photographer” often implied. Neither he nor his African American peers could have avoided the label in his United States — and probably not in ours. In fact few would have wanted to renounce it entirely. Instead the black photographer’s struggle has been to expose the lie that separates “black art” from “art.” Photographers from Anthony Barboza to James Van Der Zee have insisted that grounding one’s art in the black experience does not disqualify one from entering the photographic mainstream. It is an argument that white publishers, critics, and curators have been reluctant to accept.”

Well this same resisting and fear of the label black photographer still exist. From a broader context let’s look at the population in the United States for example, the census shows 12-13% African American population. Given the history of slavery and the civil right movement, it’s hard to factor out race in most things, even if it goes unsaid. In any professional field, a black person is more likely to stand out in the eyes of others due to many factors, one being what certain histories have taught us traditionally. Reviewers and editors in the editorial photojournalism world asked myself and other photographer of color that I’ve spoken to in the past: Why don’t you have more white people in your portfolio? or Why is your portfolio all black people?; as if this made their work of any less significance within the broad scale of photography. Most likely it didn’t fit within most brands that those reviewers/editors where representing. I was even asked about this from other people of color within the industry.

Louis Draper didn’t want to be looked at as a “black photographer,” but these are the same people who where represented in his images. Draper was a black man and lived a familiar existence as his subjects did. Photography is about a feeling to me. There has to be certain relationships I have to the subject or situation for me to be interested in to raise my camera. From my experience, when the lens is turned towards the black experience, and does not fit a certain aesthetic or trend of the time period, then it indeed is disqualified from the photographic mainstream. These artists struggle to get in until they give in or people realize the potential of the work long after the person is gone. This is where photography collectives like Kamoinge arise.

I believe different times bring different aesthetics, obstacles and context but certain standards just get repackaged. Many photographers today are facing the same dilemma as Mr. Draper, only now there are different aesthetics, obstacles and context, photographers of color are still putting one foot into the mainstream for survival and keeping the other out for what they truly stand for and quite frankly why they picked up a camera in the first place. The number of photographers of color making work today whose talent level in the mastery of aesthetics in photography are vast, also a number of those aesthetically pleasing projects are adding to the conversation of art history, but only a few are being recognized by the mainstream gatekeepers of the photo world. These gatekeepers still exist even in a world with Instagram. The only solution may be to create a platform from photographers of color just as equal to the mainstream platforms. Back in the 1970s when black artist like Frank Bowling and Melvin Edwards were fighting to be shown in places like the Whitney, where was/is the black equivalent to institution such as the Whitney, which carried the same economical power and distinguished validation?

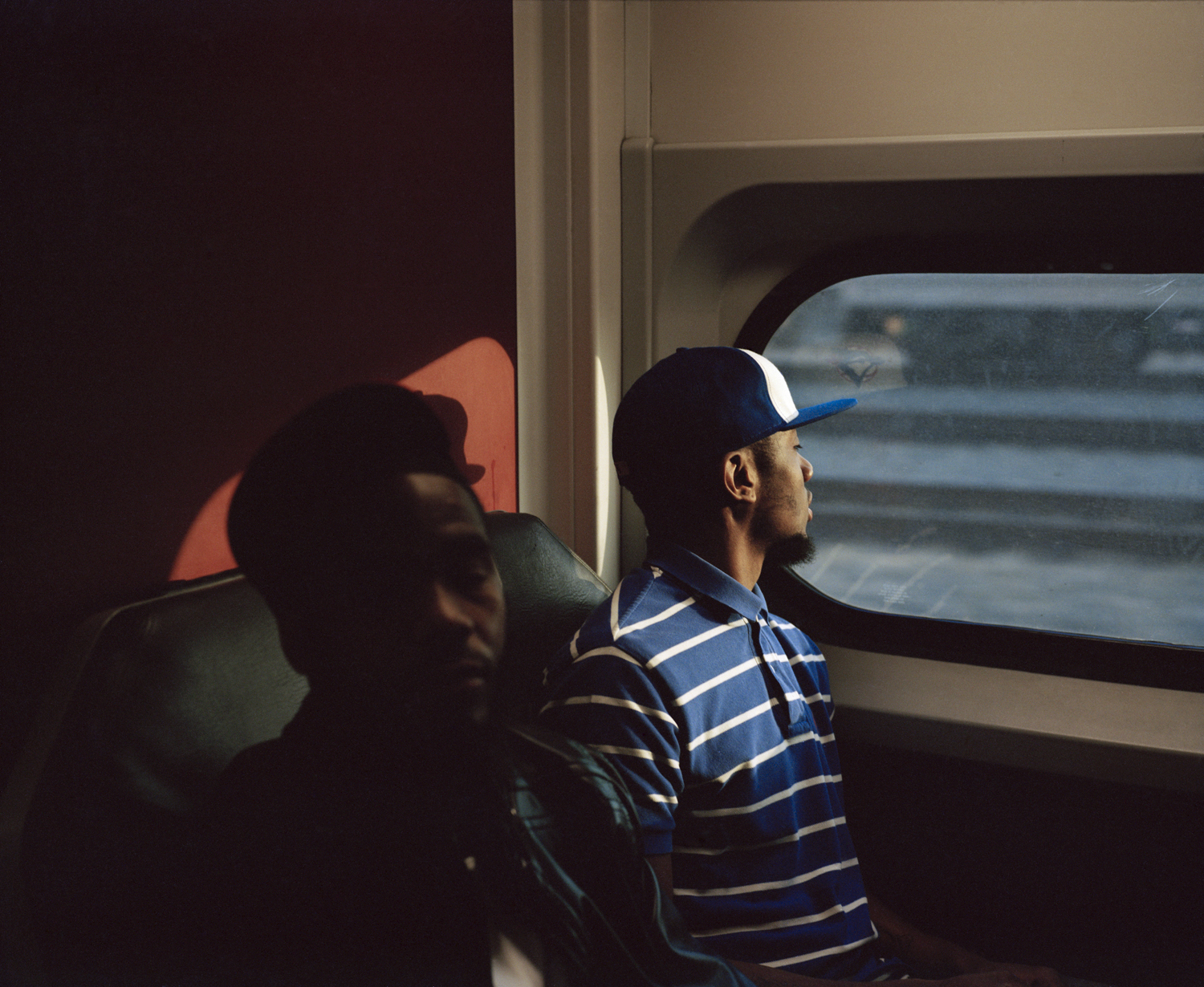

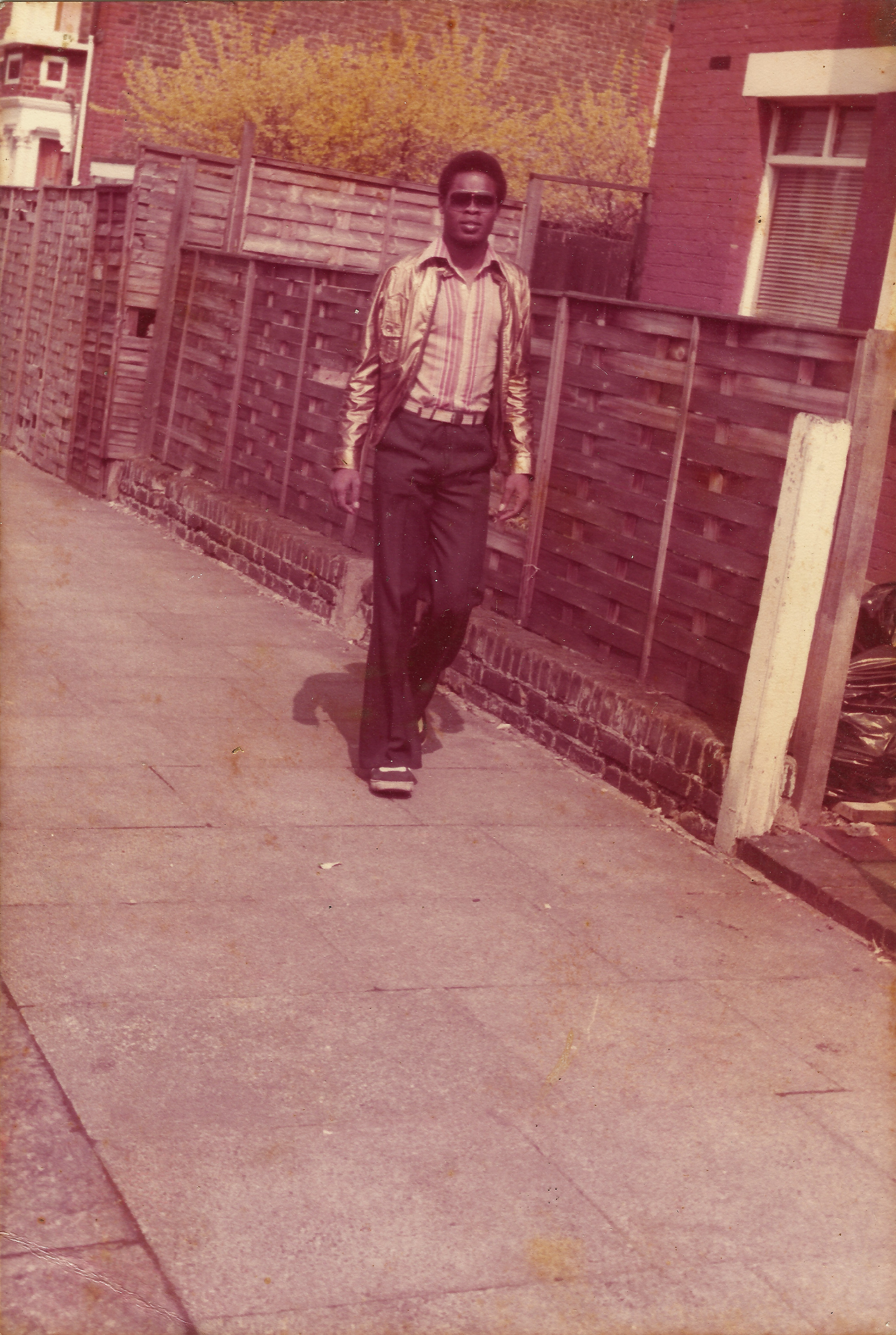

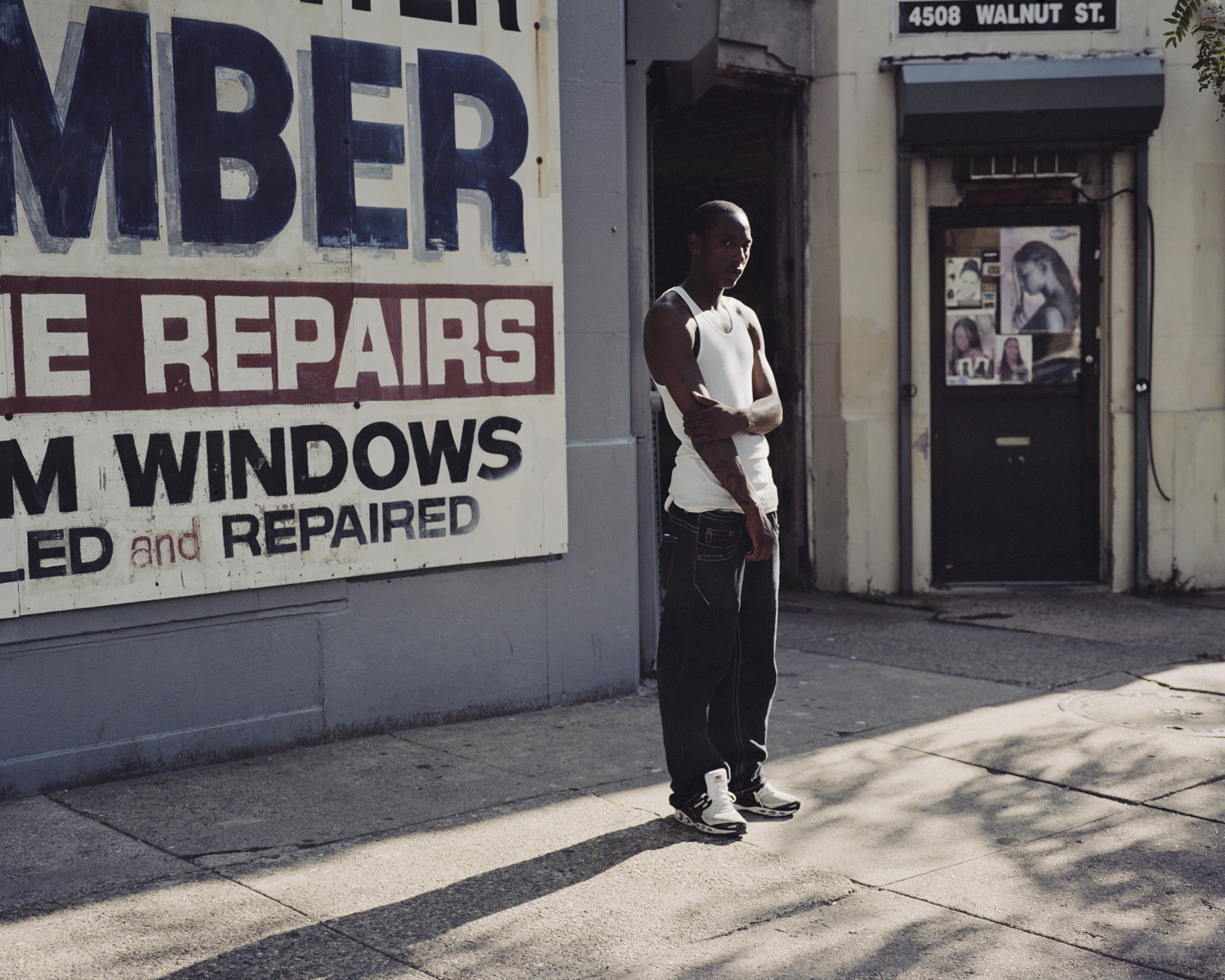

Aaron Turner (b. 1990) is a photographer and educator currently based in Memphis, TN. He uses photography to pursue personal stories of people of color, in two main areas of the U.S., the Arkansas and Mississippi Deltas. Aaron has a strong interest in the role that documentary photography plays in both the art and journalism worlds, and the crossover this creates in contemporary photography.

All images featured by Aaron Tuner are from his series, "Black Alchemy"

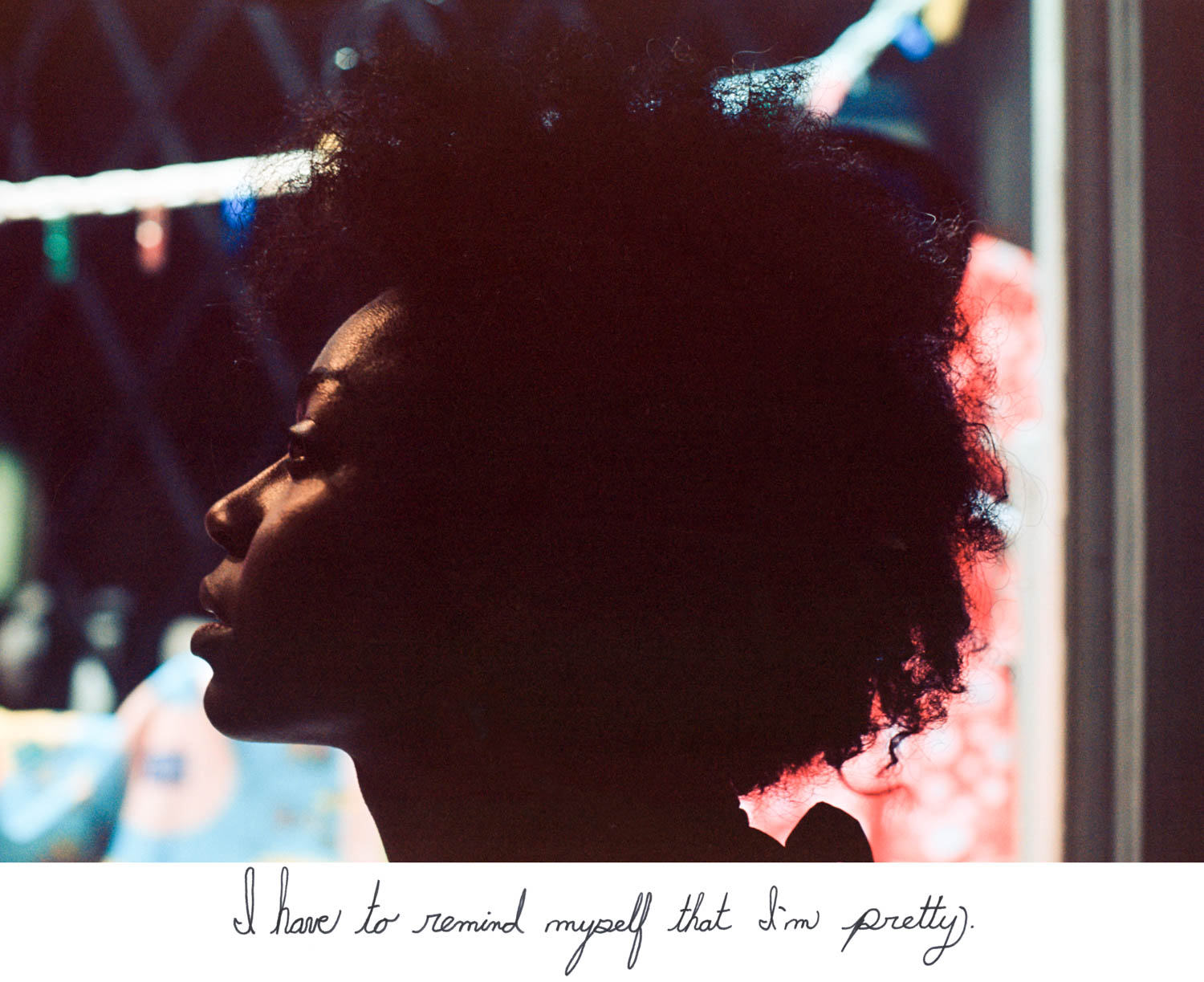

HannaH Price

To me, to be a photographer of color means that today racism still exists. We are are all labeled by our appearance and race happens to be the main factor. I am a Black American woman, and I am artist who uses photography to express the oppression of such a generalized label.

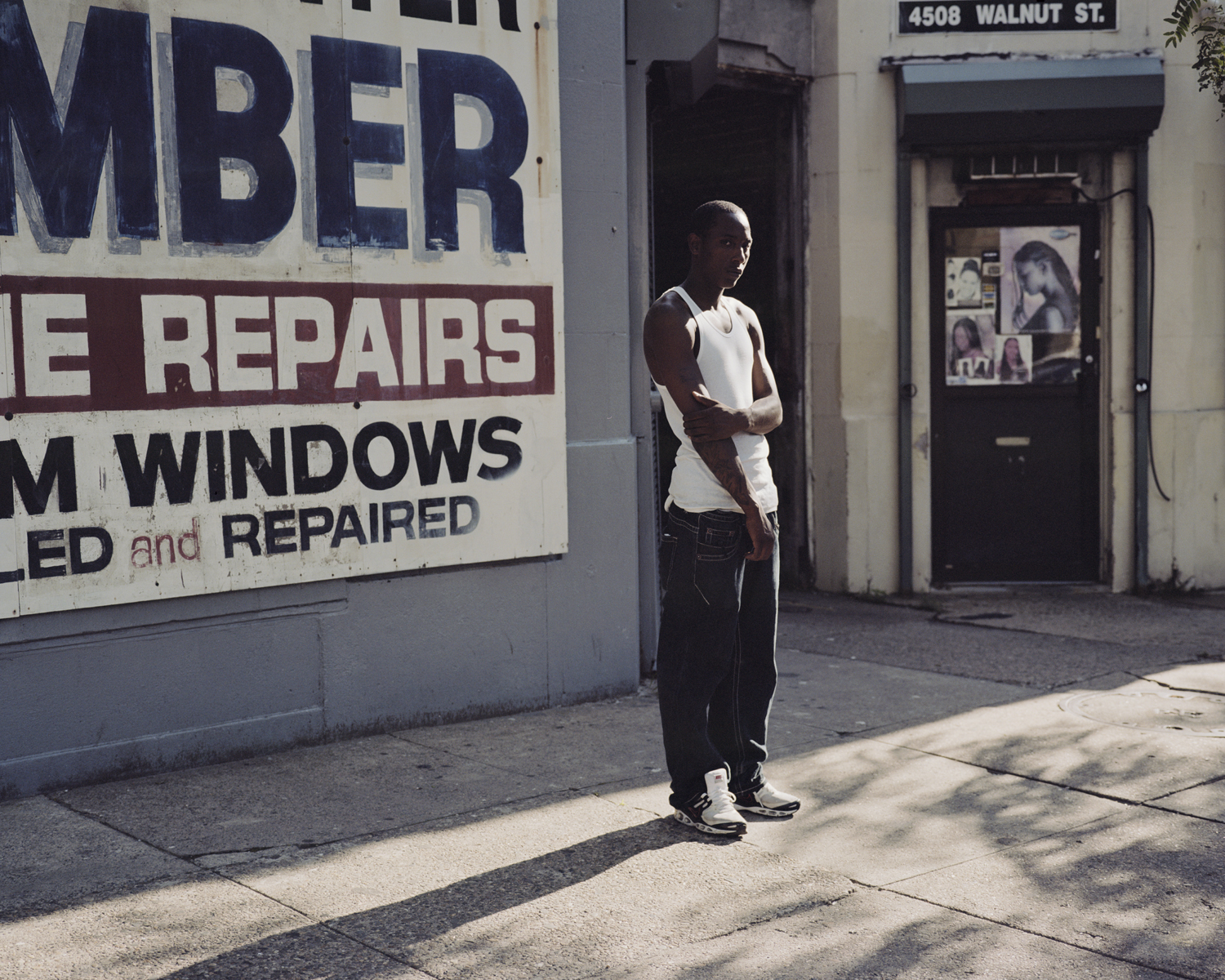

Raised in Fort Collins, Colorado, Hannah Price (b. 1986) is a photographic artist and filmmaker primarily interested in documenting relationships, race politics, social perception and misperception. Price is internationally known for her project City of Brotherly Love(2009-2012), a series of photographs of the men who catcalled her on the streets of Philadelphia. In 2014, Price graduated from the Yale School of Art MFA Photography program, receiving the Richard Benson Prize for excellence in photography. Over the past six years, Price's photos have been displayed in several cities across the United States, with a few residing in the permanent collection of the Philadelphia Museum of Art.

All images featured by Hannah Price are from her series "City of Brotherly Love"

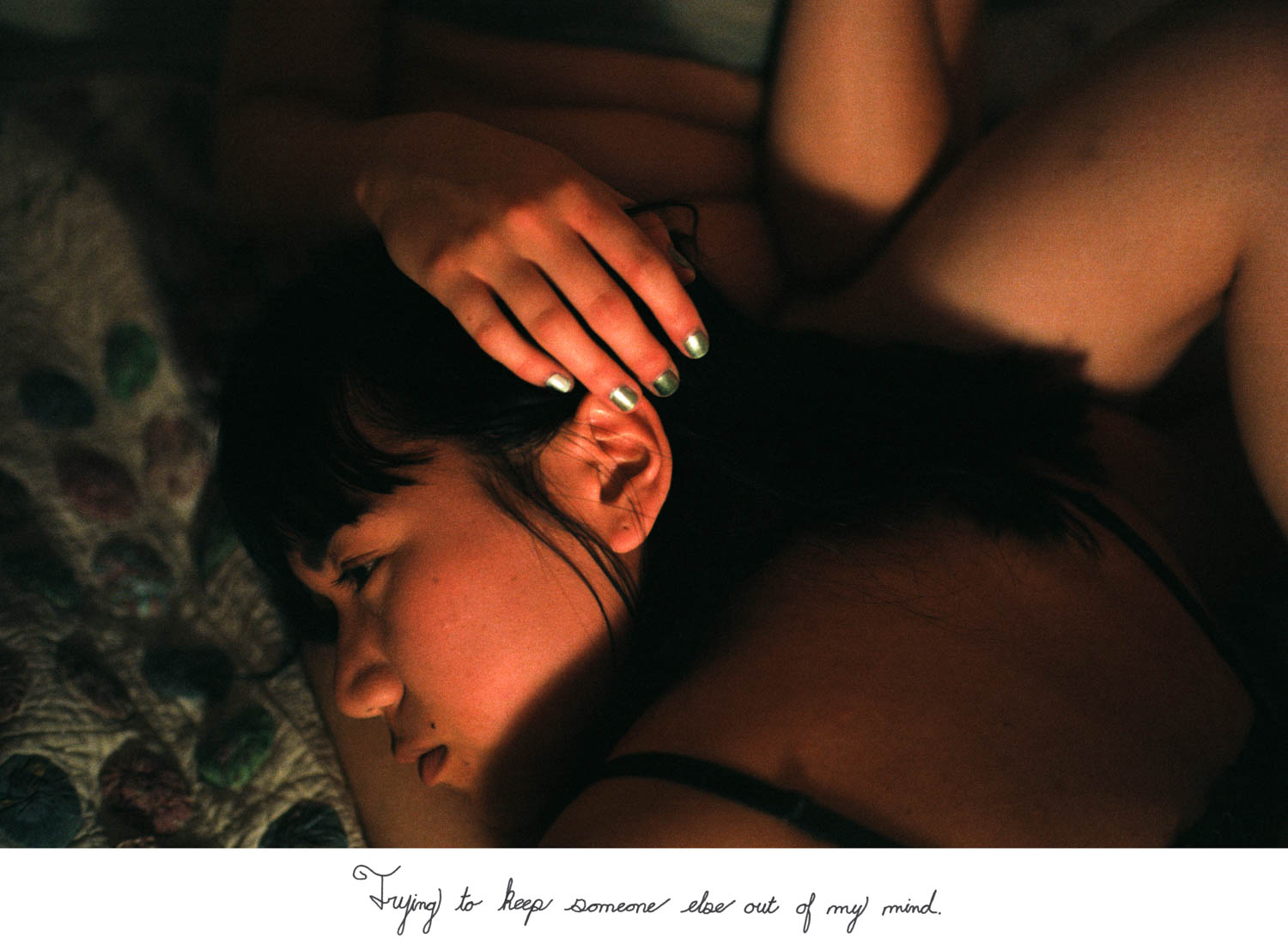

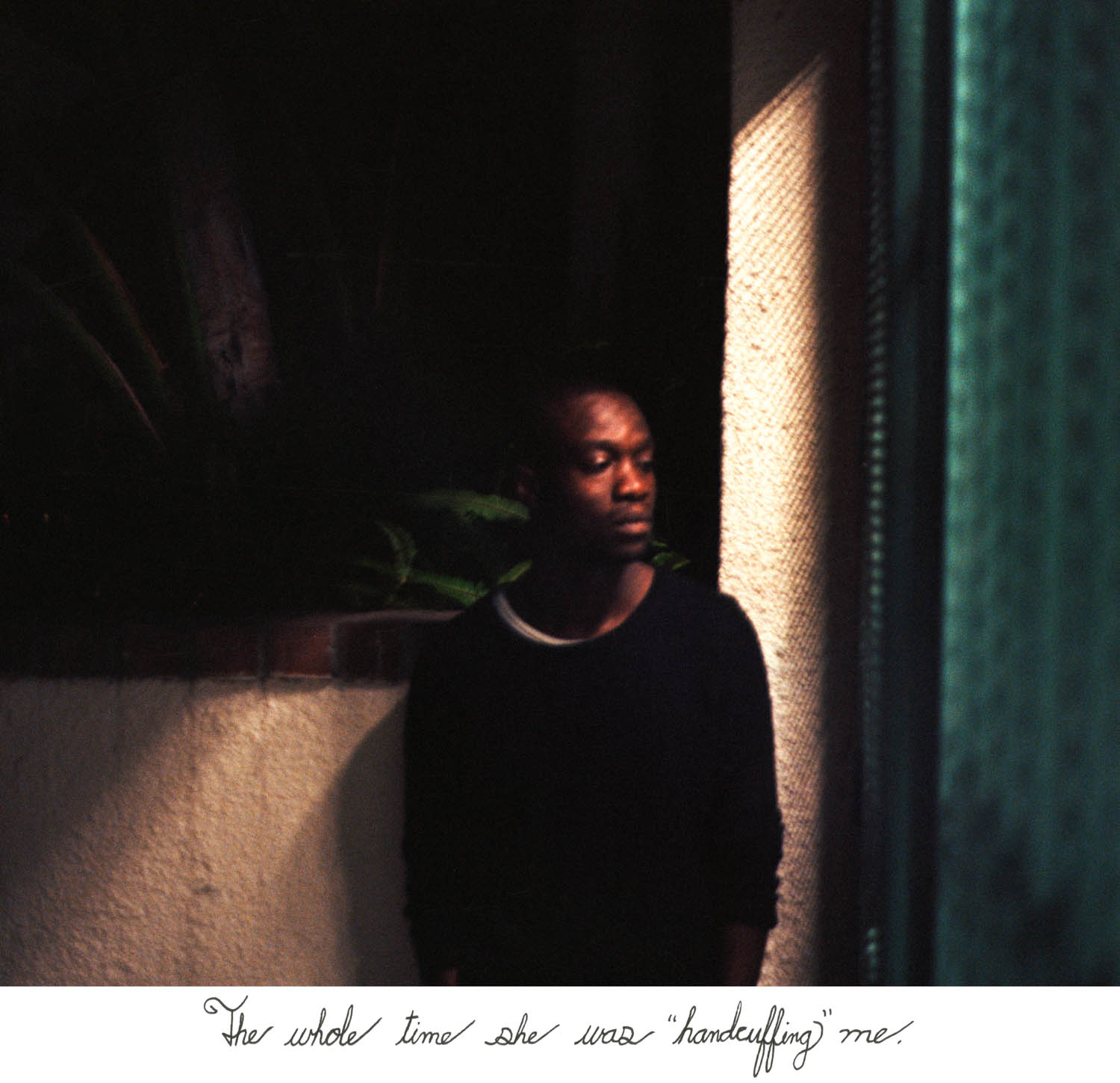

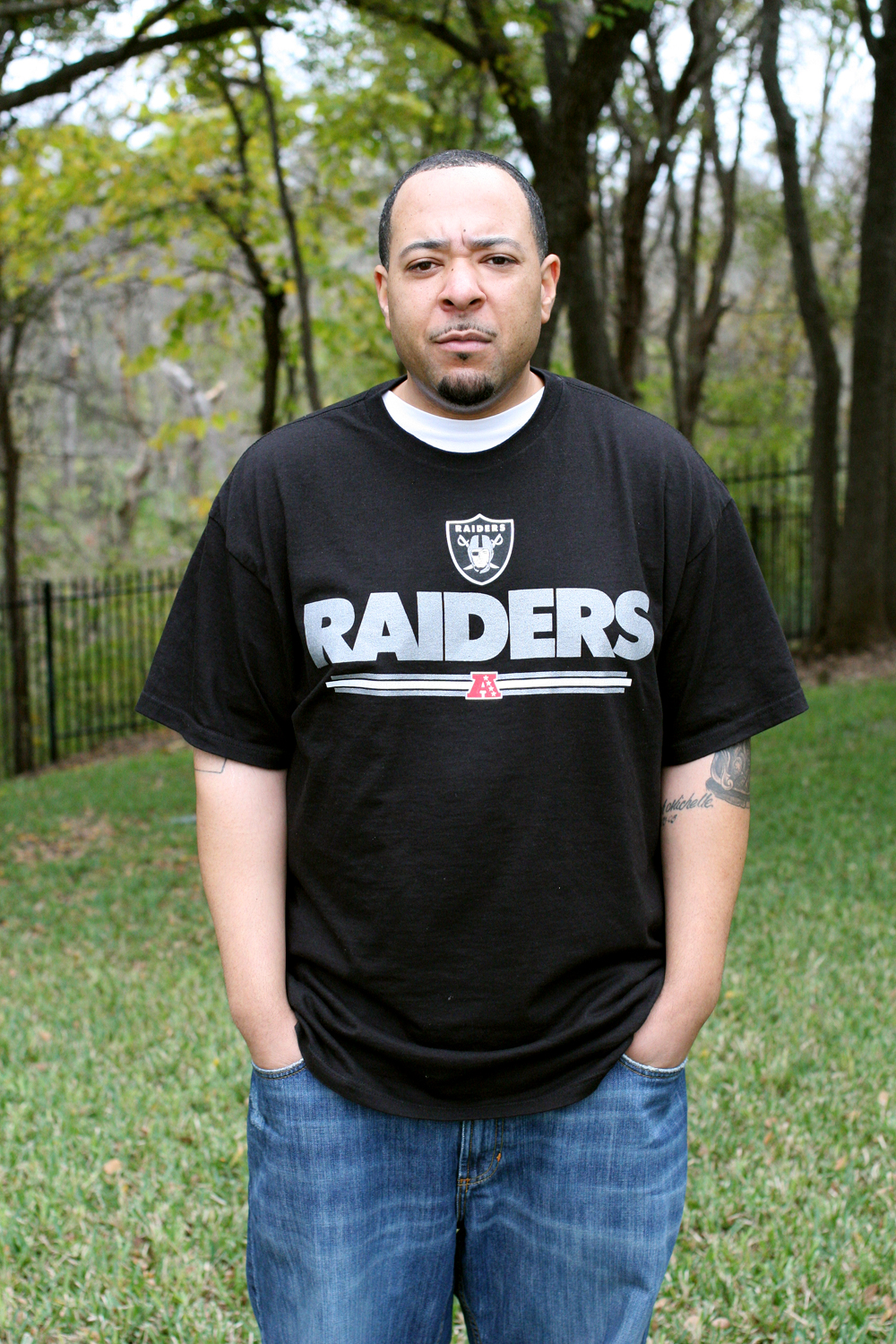

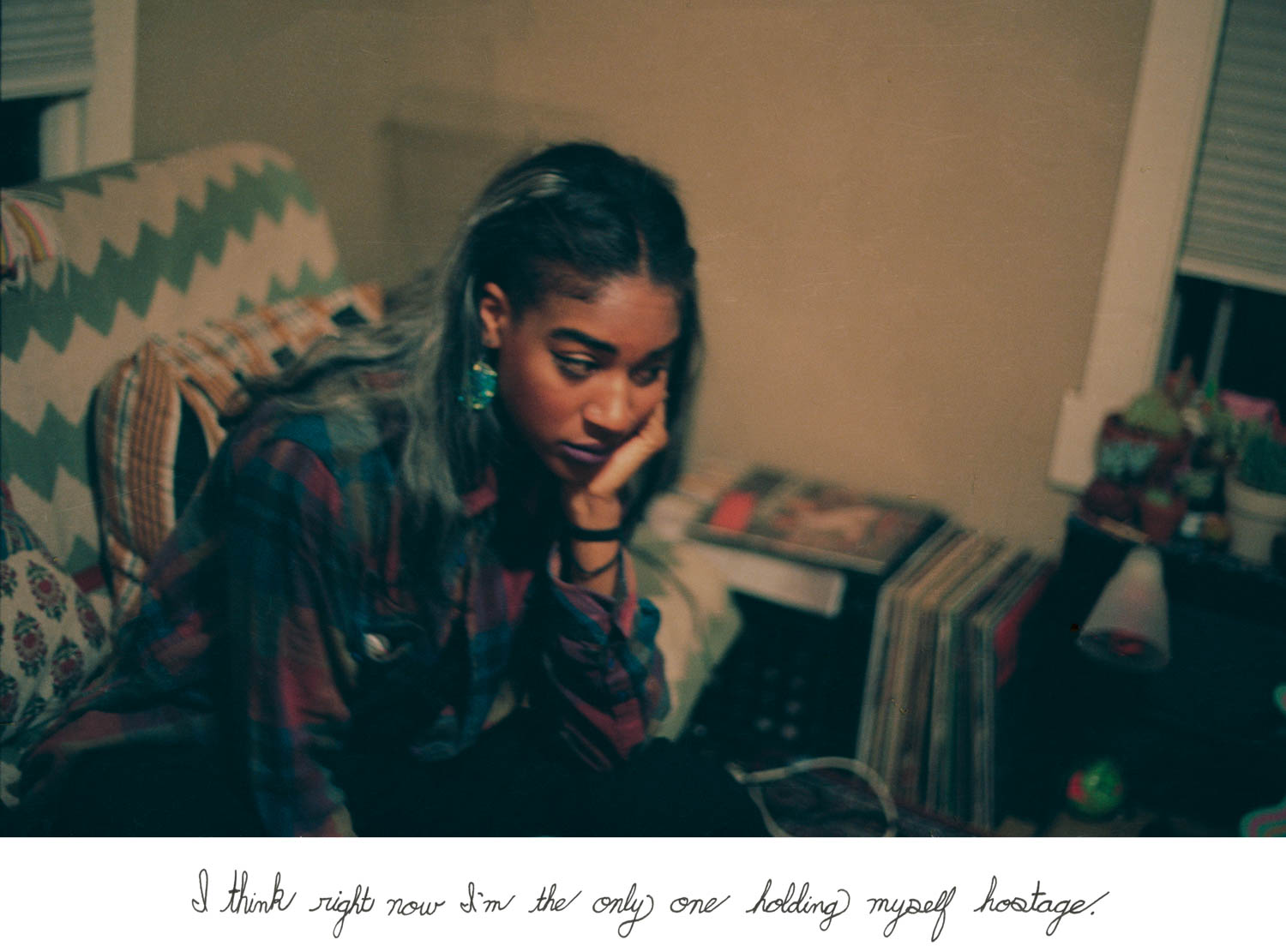

Edward Cushenberry

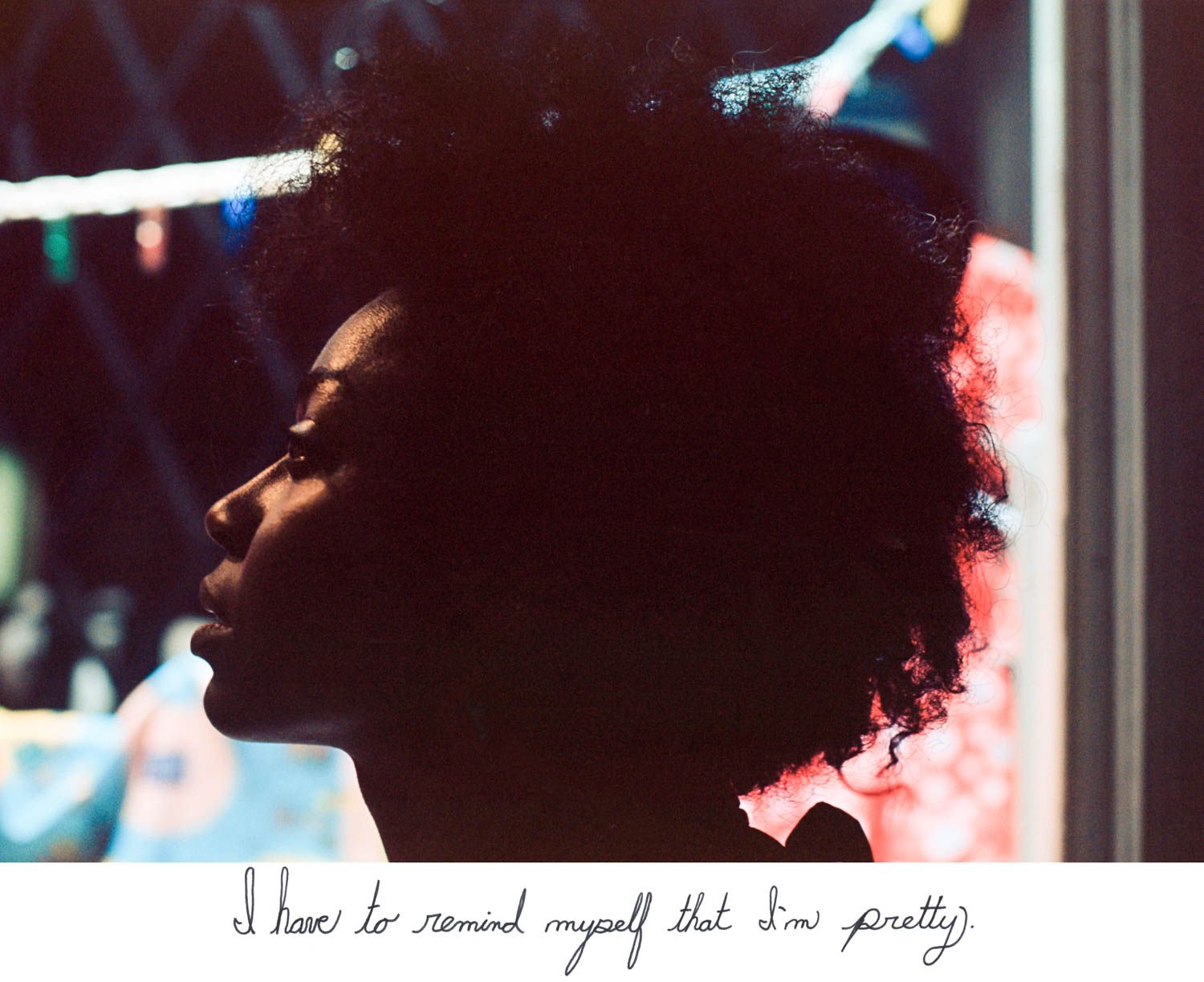

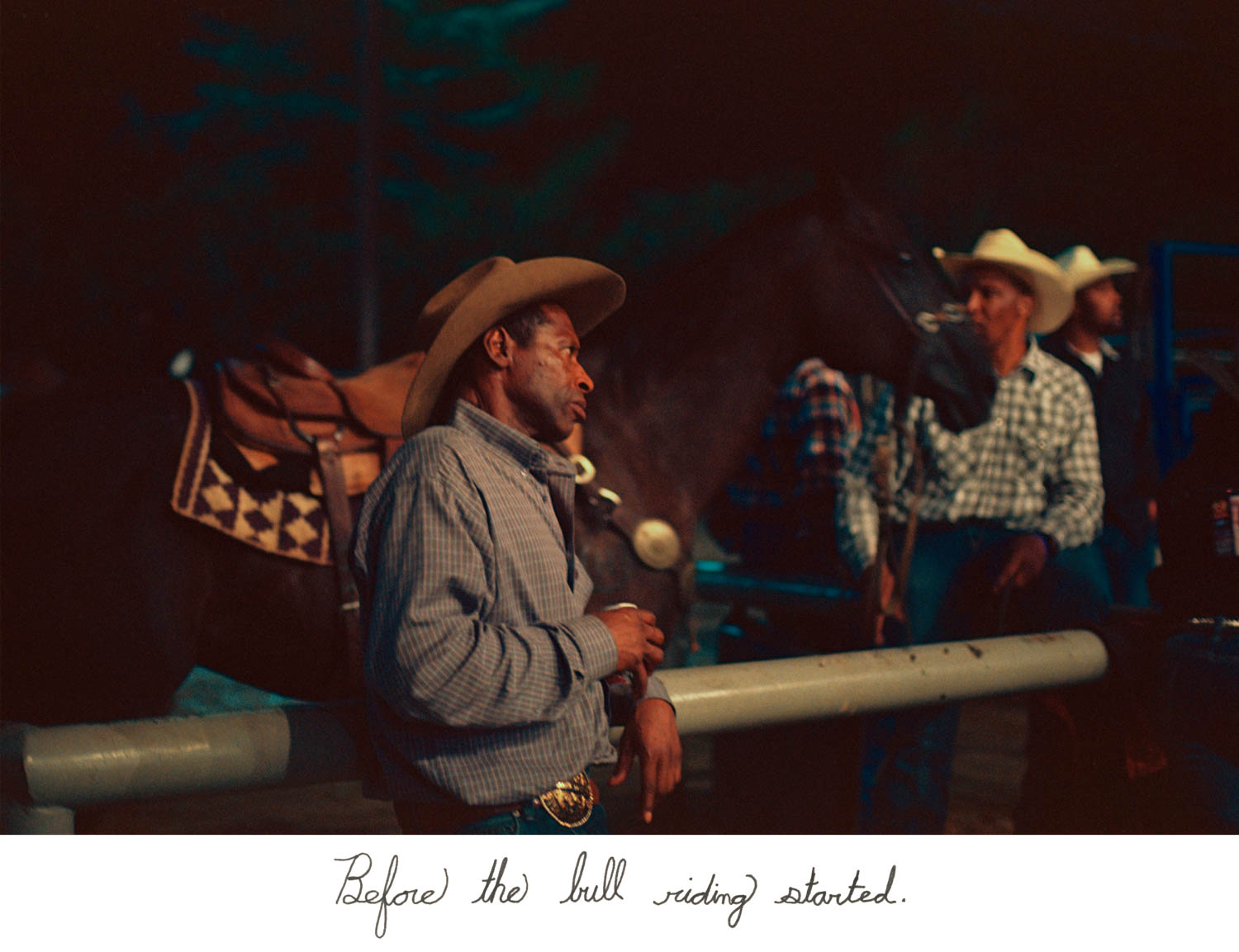

Having the opportunity to make work that’s a reflection of who I am and where I’m from so that I can show that there’s not a universal way to be black. I grew up in Huntington Beach (a predominately white city located in Orange County, California) and even to this day, I still have my “blackness” questioned. I’m constantly photographing my friends because we have similar stories about being criticized for not following the “rules” that are placed upon us. I see a lot of myself through my friends and especially through their words. I’ve been working off and on, documenting black cowboys and black rodeos to show the many subcultures and histories that make up the black community. One of my biggest areas of focus is my dad because he is one of the few people in my life who has always been there for me. To be honest, I never started photographing my dad as a way to dispel the stereotype of “The absent black father” because that stereotype never resonated with me. But I’m constantly reminded that stereotype is synonymous with “blackness” and it’s something I disagree with.

Edward Cushenberry was born and raised in Orange County, California, which was cool for a moment. Now he lives in the Los Angeles/Pasadena area where he splits his time between photographing his life and drawing everything else that's going on in his world, in an attempt to merge real life with romanticism. Edward received his BFA from the Art Center College of Design in Pasadena, California.

All images featured by Edward Cushenberry are from his series, "These are the moments that keep me up at night"

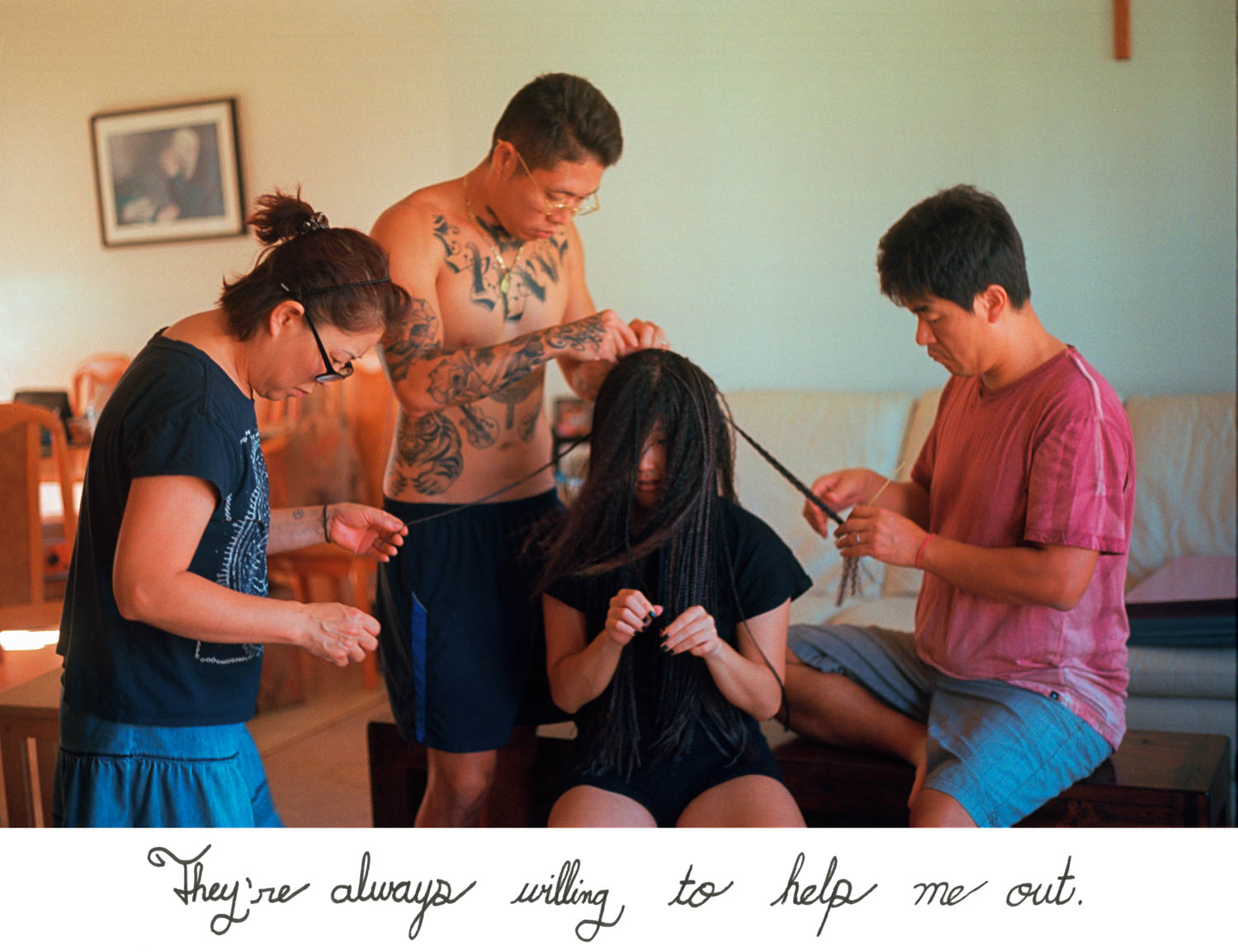

sonseree verdise gibson

It actually took me a long time to view myself as a photographer of color. I am not sure why. Although my work has always been based on culture and dialogue – I just never viewed myself in that way. I think a part of me just viewed that type of labeling as a negative. Actually, that is exactly what I did. It feels like there’s always this expectation that you are somehow supposed to just document a specific group. Somehow you are creating work that speaks to only a specific group. If you are a photographer of color, there is no possible way that you are able to branch out beyond those expectations and photograph a world that is not your own.

Over the years I’ve actually embraced it. The reason for that is because I began to embrace those photographers that are also photographers or artists of color. Photographers and artists like Carrie Mae Weems, Adrian Piper, Kara Walker, Lorna Simpson – the list goes on and on. These artists are not closed off to who views their work. Anyone can appreciate and understand where they are coming from; of course, sometimes it’s some more than others.

They speak to a multitude of people; not just those in their own cultural groups. That’s what I love. That is why I have learned to embrace being a photographer of color. It’s due to these artists, and others who open themselves up. They embrace the conversation between them, and everyone else. That to me is what it means to be a photographer of color.

Sonseree Verdise Gibson received a Bachelors of Science in Criminal Justice from California State University, Sacramento in 1999. In 2006 she received a Bachelors of Fine Arts in Photography from Savannah College of Art and Design in Savannah, Georgia. For the past several years she has produced work that examines both culture and self. Currently she am lives, works and creates art in the city of Austin, Texas.

All images featured by Sonseree Verdise Gibson are from her series "Melungeon Descendants"

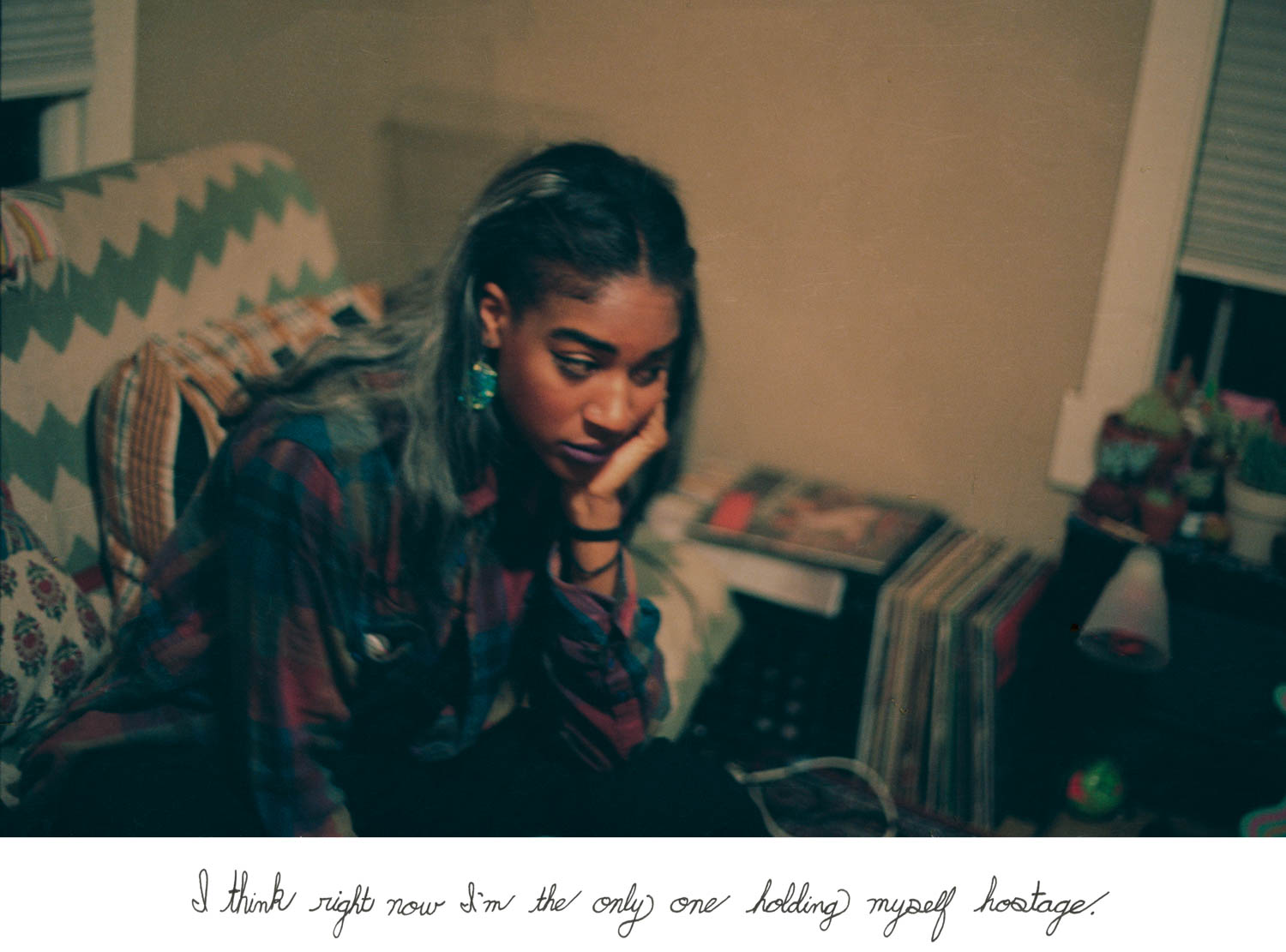

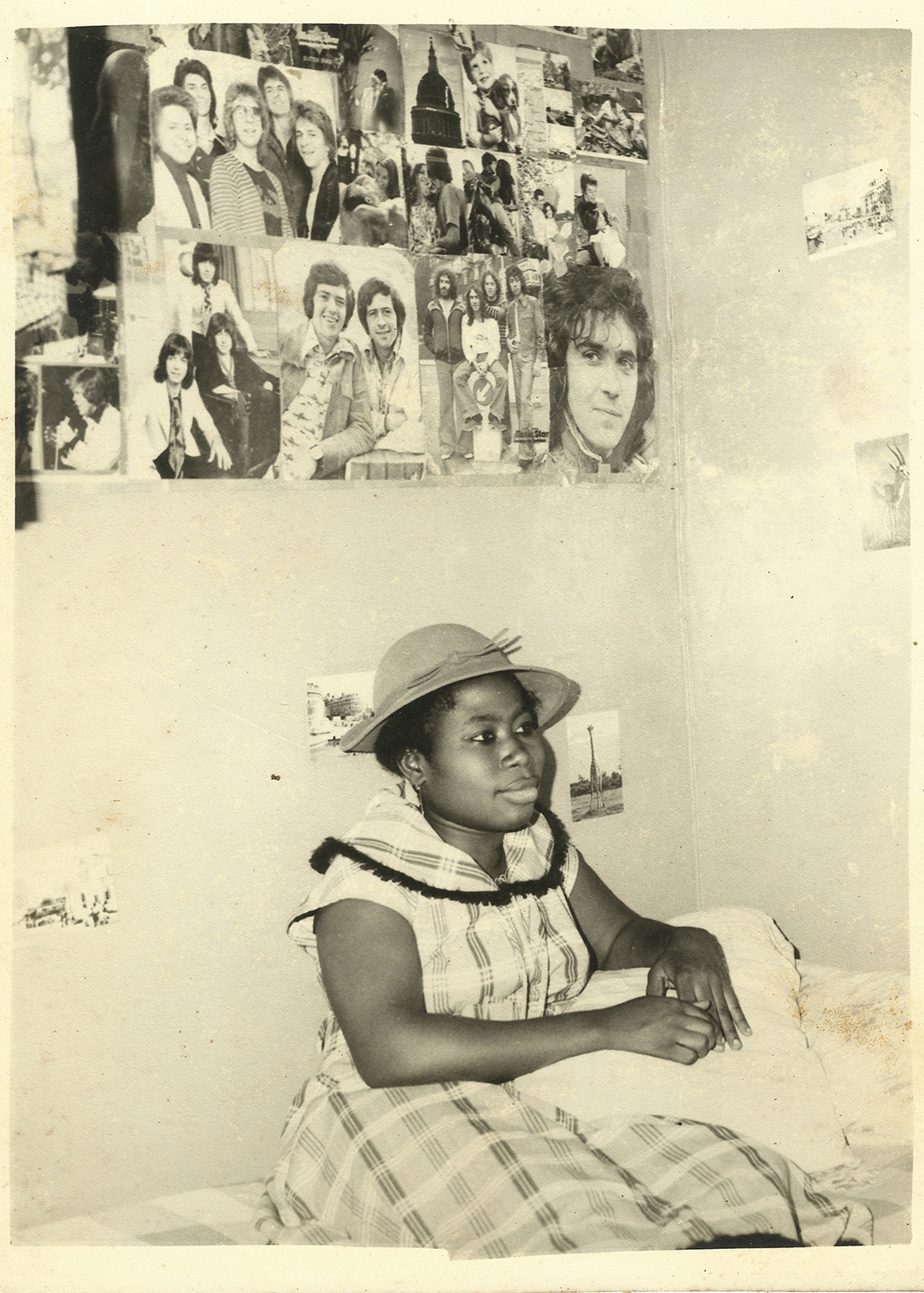

Emma Uwejoma

Before it never meant anything. I was never quite in myself. I didn't connect to my true identity. Maybe to me being a child or oblivious or naive?

These self-blame excuses, I can go on forever.

Forever?

That word.

How far in my forever can I reach, despite wearing this obstacle on my skin?

My magazine covers, storybooks, dolls. Dominated by the white glaze. The identity crisis questions that played at the back of my mind. Never knew the answers.

I was a quiet child, held emotions back, speaking back, expressing back, and questioning back.

Secondary school. The triggered memories of letting 'friends' nickname me 'black sheep' and 'nigger'. Did it affect me? I never considered myself as black at the time. So did it really matter?

What it means to be a photographer of colour for me today? It means I want to be understood and heard. For more people of colour to view my personal discovery journey as a relative visual diary. And for others to understand my journey and see past my stereotyped skin colour to the realisation of how it feels to be a black British woman in society.

Emma Uwejoma was born and raised in Bournemouth, UK. Currently living in Brighton, UK, where she continues her artistic practice based on a self-portraiture analysis on African culture and female identity. Uwejoma graduated in a BA Honours Documentary Photography in class 2014 at the University of Newport.

All images featured by Emma Uwejoma are from her series "Ngwako"

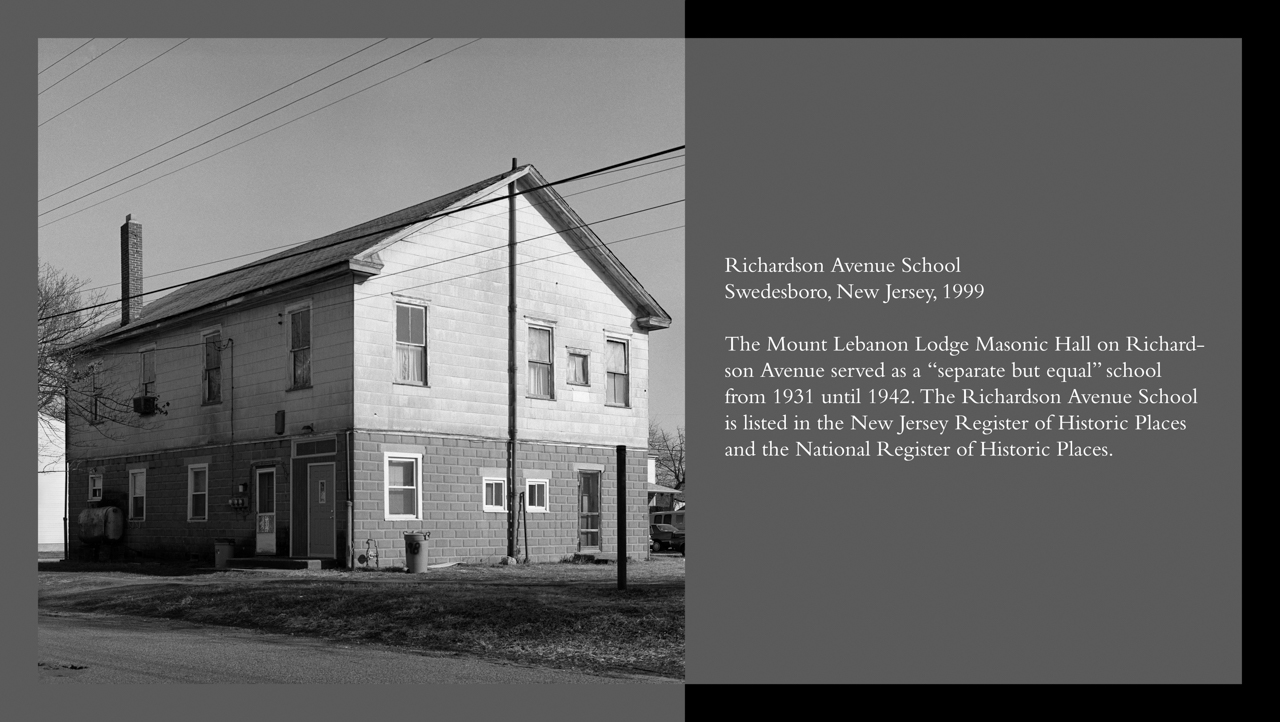

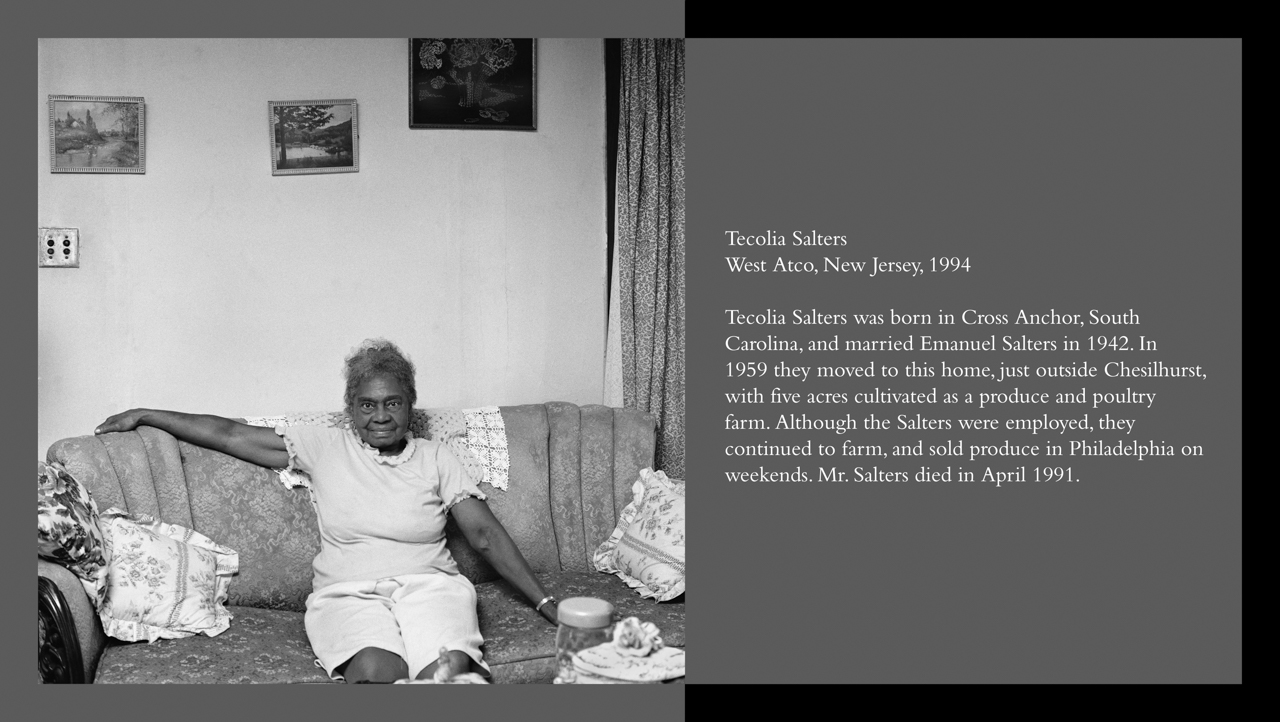

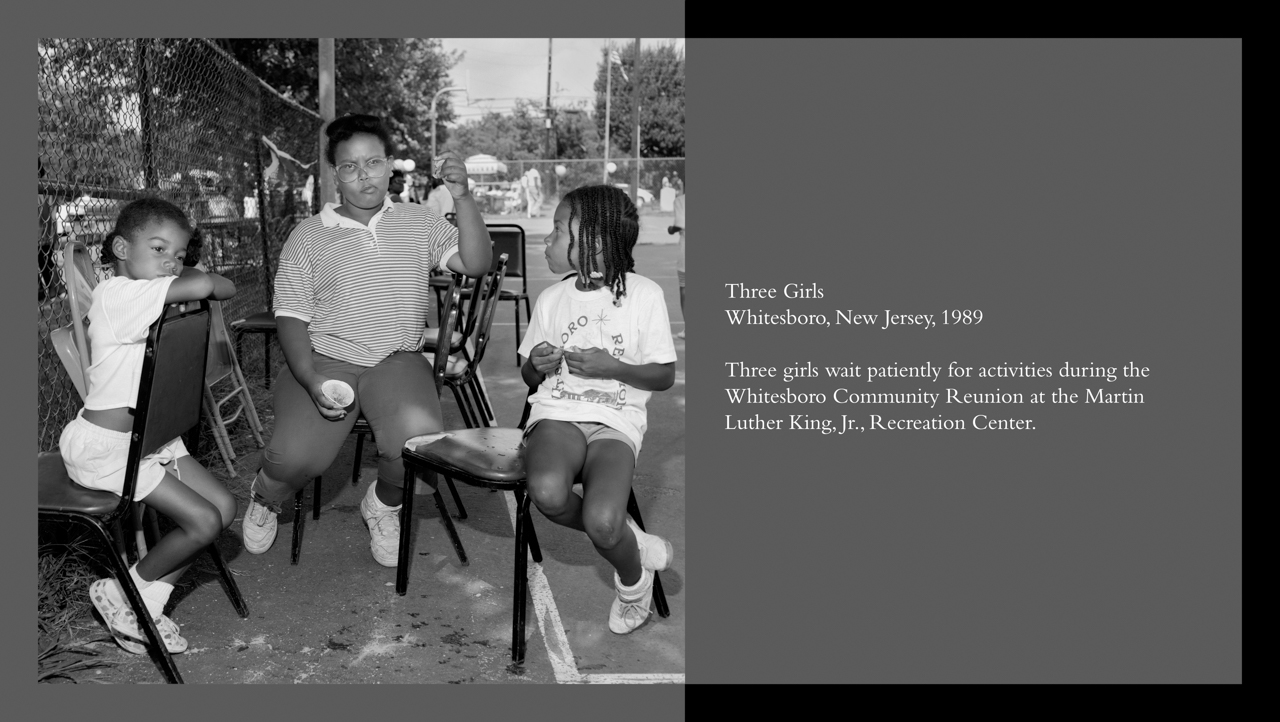

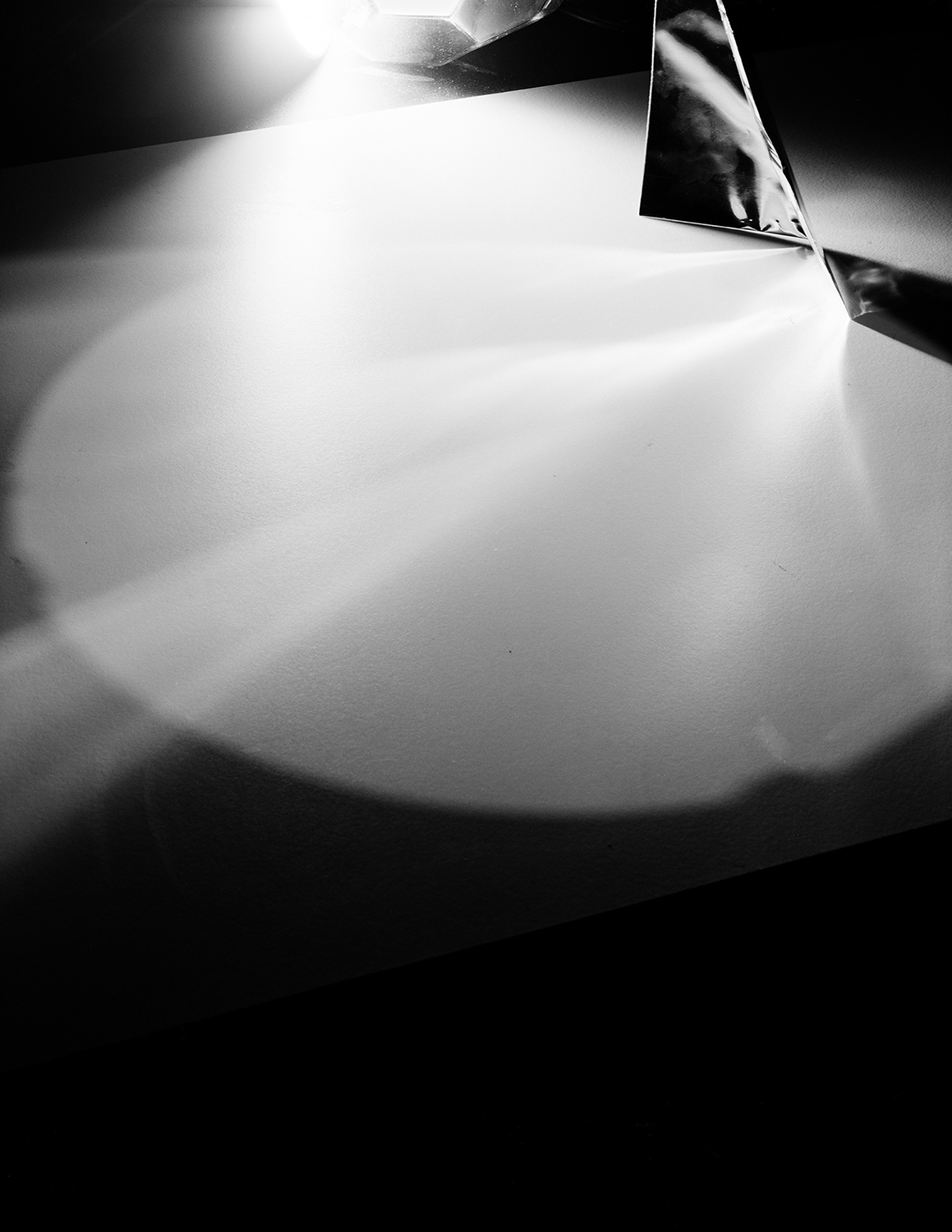

wendel white

To answer this question I will begin by defining (if that is possible) my location within the heritage of people defined by the racial construct of blackness and broadly known as African American. My narrative (from both parents) originates in the sexual exploitation of slaves in the US and the Caribbean. Reaching back to the first half of the 19th century, I know that my genetic origins flow from the use of slaves by Europeans as an opportunity for forced sexual adventure, while simultaneously adding to the human inventory, wealth and resources of the plantation. This narrative is supported by oral history as well as documentary and genetic evidence. American culture (through the use of official government documents) has defined the individuals that make up my genealogical heritage by various terminologies since the 19th century including; mulatto, colored, negro, and black.

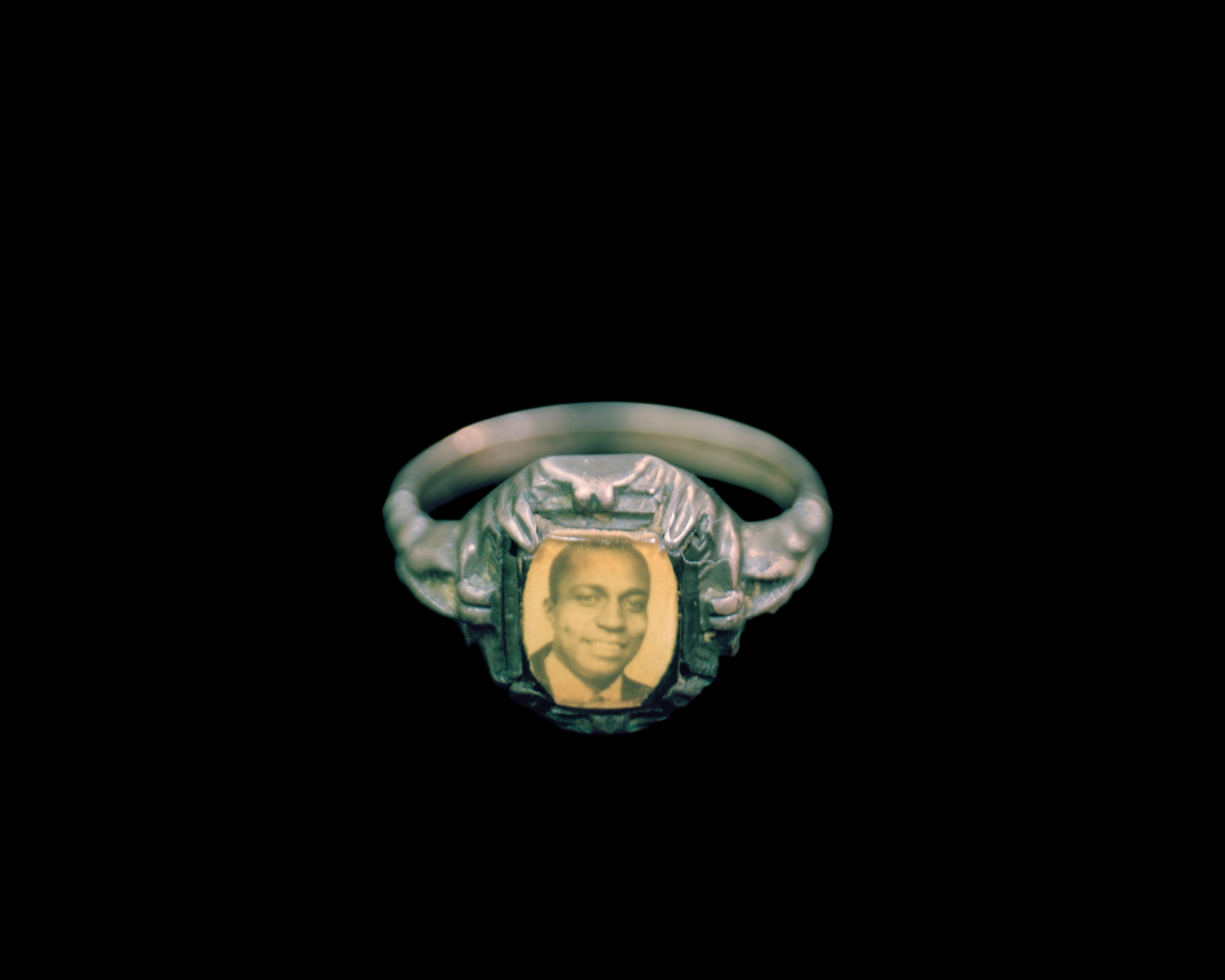

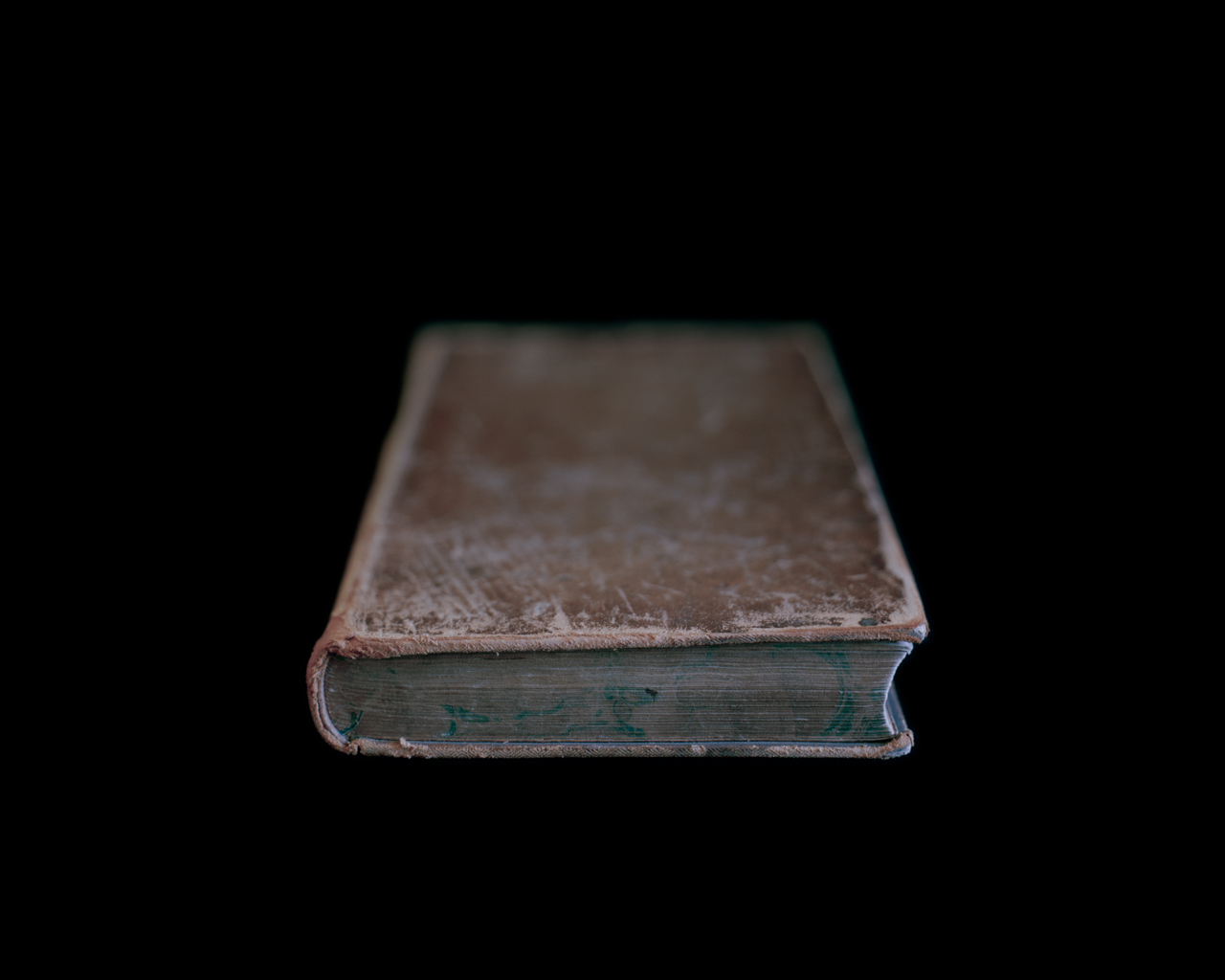

My concerns, and thereby my work, are centered on these complicated histories and definitions of race in American culture. Our present racial, ethnic and cultural schisms are a result of the many unresolved and ineffective efforts to invent racial boundaries, establish and maintain an American identity based on specific European ethnic/tribal origins. All of my projects during the past few decades are efforts to reveal/represent the means by which racial boundaries (along with class and economics) have been and continue to be a means for maintaining the hierarchies of privilege. In particular my attention is drawn toward African American history, spaces (landscape and architecture) and material culture as evidence of the shifting but purposeful definitions leading to systemic segregation, mass incarceration, persistent poverty, and violence toward the black community.

Wendel A. White was born in Newark, New Jersey and grew up in New York, Pennsylvania, and New Jersey. He was awarded a BFA in photography from the School of Visual Arts in New York and an MFA in photography from the University of Texas at Austin. White taught photography at the School of Visual Arts, NY; The Cooper Union for the Advancement of Science and Art, NY; the International Center for Photography, NY; Rochester Institute of Technology; and is currently Distinguished Professor of Art at Stockton University. His work has received various awards and fellowships including a John Simon Guggenheim Foundation Fellowship in Photography, three artist fellowships from the New Jersey State Council for the Arts, a photography grant from the Graham Foundation for Advanced Studies in the Fine Arts, and a New Works Photography Fellowship from En Foco Inc.

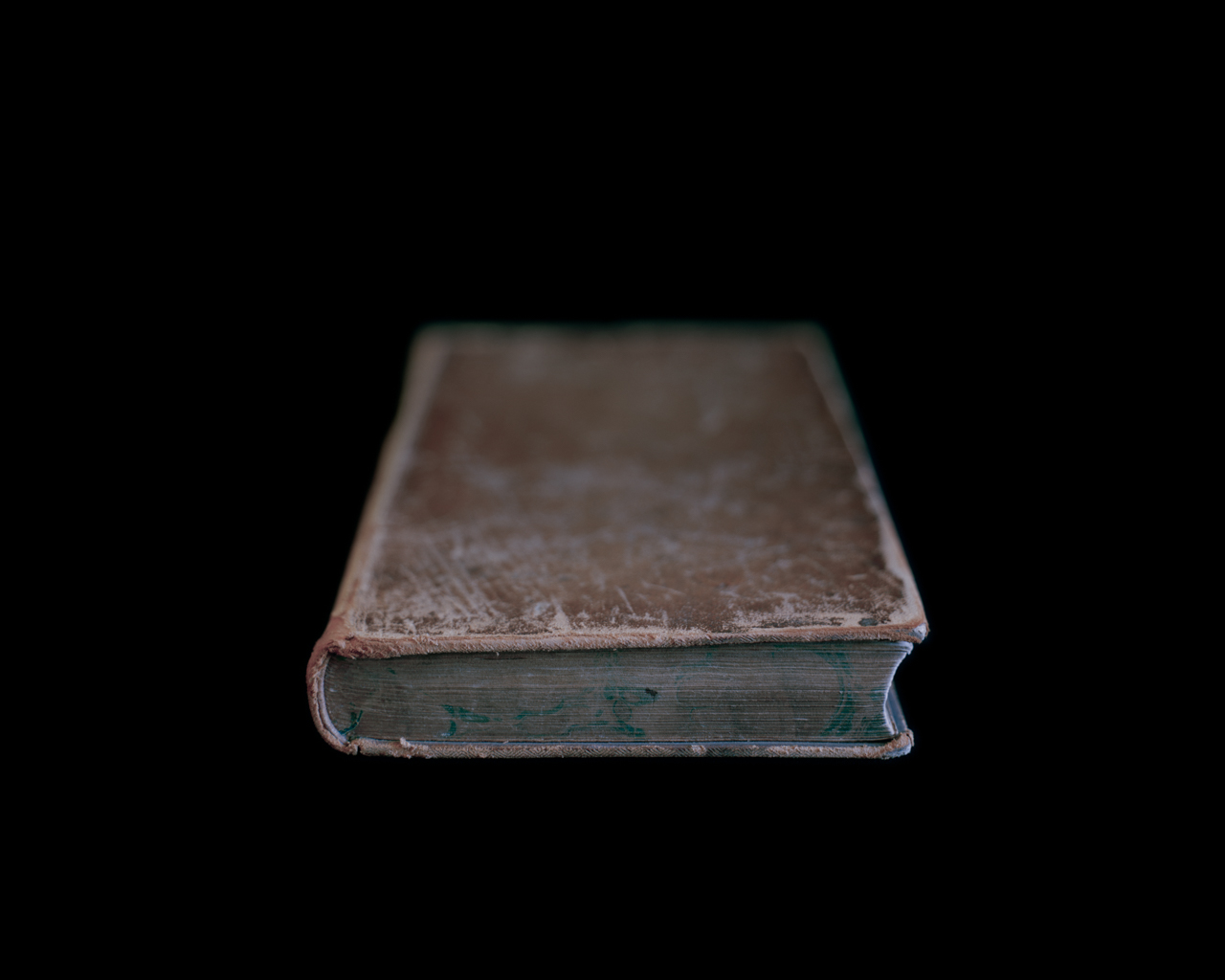

All featured images by Wendel White are from his series "Schools for the Colored" and "Manifest"