Q&A: Adama Delphine Fawundu

By Hamidah Glasgow | March 11, 2021

Organized by Strange Fire Collective (SFC), An Active and Urgent Telling features the work of six contemporary artists working with photography to honor the weight of lived experience through an intersectional lens. Stemming from SFC’s mission, this exhibition centers artists for whom questions of identity deeply affect their relationship to representation. The works included engage with ideas of visibility and invisibility, the reality of lives that exist outside of, or in opposition to, expected and enforced social norms, and the social and political power of speaking one’s truth. Each artist contributes nuance to a redefinition of the commonly understood fabric of difference through an active and urgent telling of their own lived experiences.

Original, in-depth interviews with each exhibiting artist will be posted on www.strangefirecollective.com during the exhibition to illuminate a more thoughtful understanding of the artists and their work. Exhibiting artists include Jennifer Ling Datchuk, Adama Delphine Fawundu, Penny Molesso, Rachelle Mozman Solano, Irene Reece, and Chanell Stone.

Adama Delphine Fawundu -

Adama Delphine Fawundu is a photographer and visual artist born in Brooklyn, NY, to parents from Sierra Leone and Equatorial Guinea, West Africa. She received her MFA from Columbia University. Fawundu uses photography, printmaking, video, sound, and assemblage as an artistic language.

Fawundu co-founded and independently published the sold-out book MFON: Women Photographers of the African Diaspora. The critically acclaimed book MFON led Fawundu on a book tour that included talks at The Tate Modern, The Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, Harvard University, and many other institutions.

Ms. Fawundu was nominated for and won the Rema Hort Mann Emerging Artist Award, named OkayAfrica’s 100 Women, impacting Africa and its Diaspora and included in the Royal Photographic Society’s (UK) Hundred Heroines, in 2018. Ms. Fawundu’s awards also include New York Foundation of the Arts Photography Fellow, Brooklyn Art Council Grant, and Open Society Foundation Community Fellow. She was commissioned by the Park Avenue Armory and New York University to participate in the 100 Years 100 Women exhibition commemorating one century since the ratification of the 19th Amendment.

HG: Tell me about your trajectory as an artist, publisher, and curator?

ADF: I am often thinking about the archives and the telling of stories.

How do we interrogate the past to create equitable and just futures? As an artist, publisher, and curator, it is crucial for me to create space and archive perspectives that often go unrecognized. My works in these areas are my way of sharing the process of decolonizing my mind. I am interested in indigenous ontologies and intellectuality and the impact that this has on world knowledge. I consider my work an uncovering of hi(s)tories. There is so much information here that I can never run out of ideas to make work about.

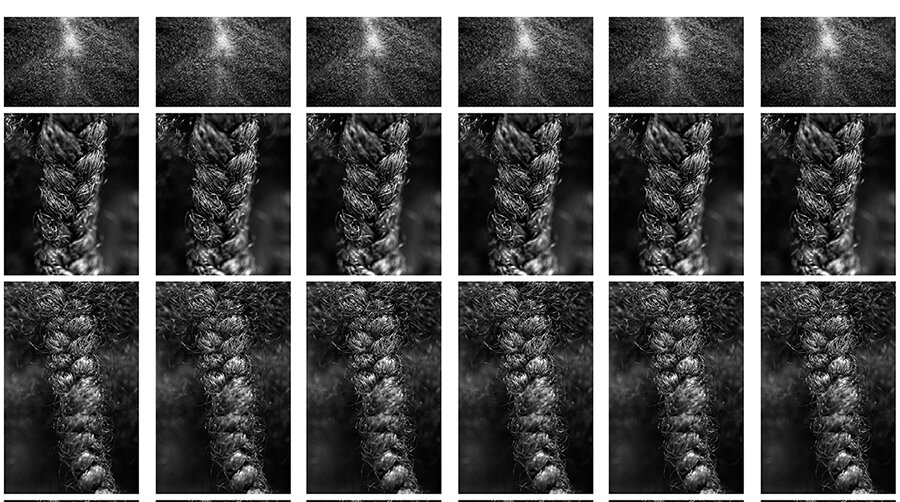

Still Image from The Cleanse video

HG: Your video work, The Cleanse, will be exhibited in the exhibition, An Active and Urgent Telling. How did the idea for this work formulate? Tell me more about the trajectory of its creation.

ADF: “the cleanse” was inspired by my research on Mende culture. I am Mende from my paternal grandmother’s heritage. I was heavily influenced by the book titled, Radiance of the Waters: Ideals of Feminine Beauty in Mende Art by Sylvia Ardyn Boone.

What does it mean to live in a society that is not obsessed with politicizing every aspect of your body? This book gives us a glimpse into Mende ontology, which was quite liberating for me. It opened my eyes to a different way of seeing and experiencing the body. A central theme in “the cleanse’ is the liberation and transformation of the mind. I approached it as if I were making a new language. I thought of how languages are formed in the African Diaspora, using English (or other colonial) words with an indigenous African language’s syntax (i.e., Mende, Yoruba). I am fascinated with how the mind does that. Even forms of music such as hip hop, the blues, and jazz, organically borrow from traditional African cultures. So, I sampled trap music “make it rain,” with some Mende chanting that literally calls for the rain. I also sampled words from several writers, including James Baldwin, Gayle Jones, Toni Morrison, Sojourner Truth, and more, to create a cohesive sonic experience.

Within this experience, the viewer witnesses the transformation of straightened hair into elastic, springy hair when in contact with water.

HG: Tell me more about how Mende ontology opened your eyes and liberated your mind to different ways of experiencing the body?

ADF: One example, is respecting and caring for your body is embedded in the culture. The idea of a hierarchy based on body type is not something that is focused on. Therefore, the aging body is one that is honored and not frowned upon.

HG: This is a pivotal time in the photography world as we adjust to the waves of calls for social justice. How do you see these changes happening, or do you see changes?

ADF: This call, this need for social justice, particularly in the world of photography and image-making, is pivotal. It is certainly not a new want or need. I first became aware of the urgent need to end systemic racism, sexism, homophobia, transphobia, xenophobia, etc., etc. within many global institutions during my college years. Of course, these types of mental violence are not unique to the photography world but are present in every form of institution. During my college years (early 90’s), because of access to history, I was able to process the mental attacks projected on to my identity through school, the media, etc. The photograph and moving image played a significant role in all of this. This is what inspired me to become an image-maker. I wanted to make a change. I thought I would become a documentary filmmaker, but I fell in love with photography.

If we look at movements like the Black Arts and Nuyorican Movements (1960-the 70s), the global ballroom cultures of the 80’s led by Black and Latinx LGBTQIA communities, the Negritude Movement (1930-50s), the Harlem Renaissance of the (1920-30s), W.E.B. Dubois photographic series “American Negro” (1890-1900), and the need for Frederick Douglass to distribute as many photographs of himself as possible during his lifetime (he died in 1895), we know that this fight has been consistent in American and world history. If we consider that I have not included Choctaw, Lenape, Navajo, or any of the 562 Native movements to this colonized land that we call America…there has been a consistent call and need for social justice since the birth of this nation. Therefore, I wonder what change really looks like.

HG: Yes, indeed. Photography and its adherents have been making a case for racial justice from the very beginning with the work of Frederick Douglass. What do you see today that is different or hopeful?

ADF: 2020 was the first time I witnessed so many institutions collectively calling out their own biases. This is where the work begins; I hope that it continues within the ways these institutions function. It’s also vital for the educational institutions, beyond the art world, to assess how they are socializing children.

HG: Please talk more about this,” It’s also important for the educational institutions, beyond the art world, to assess how they are socializing children.”

ADF: I’ve taught within the New York public school system for 10 years. I could not rely on the average textbook to teach children. Unfortunately, the educational curriculum is still plagued with phobias and isms. Schools play a significant role in the socialization of children. There is no reason why a child should feel inferior based on the education that they’ve received.

Children shouldn’t learn to “other” people in school. From my experience, there is so much that needs to change.

HG: In your statement for Star Of Isis, you talk about water and hair and their significance in your work. Please tell me more about those elements and their place in your work.

ADF: Water and hair have so many meanings for me. With water, I think of how essential it is to life, whether it be humans, the earth, plants, animals, etc. I also think about its transformative nature and its historical value, such as the Maafa, also known as the Middle Passage. In addition to this, I think about water deities stemming from the specific African cultures and how they’ve made their way into the Diaspora. This is quite powerful to me. The idea that traditional African Spiritual practices have evolved within the Diaspora is quite powerful, considering erasure by colonial systems. The fact there are no gender hierarchies in this space is also notable. Hair signifies ancestral connections through DNA, cyclical transformation (especially the shape-shifting sculptural qualities of hair like mine). My hair defies gravity and changes dramatically with heat and water. Hair is symbolic of the dramatic changes that can happen if we liberate our minds – freed from the chains of colonialism.

HG: In Sacred Star of Isis, you say you generate “connective threads of exchange between the magical space of nature and the material structures of history.” I’m interested in how you use dualities in your work. For example, you use a sort of magical realism to connect your tangible, lived experience in the present with the more esoteric world of your ancestors. Similarly, you introduce sculptural, organic materials to otherwise two-dimensional photographs on the wall. Can you expand on this use of contrast/juxtapositions/dualities?

ADF: I’m often using contrasts, juxtapositions, and dualities in my work because I’m referencing the complexity of our identity. Our bodies carry so much information passed on from generation to generation, while at the same time, we are evolving. I also like to think of problem-solving in this Westernized space by tapping into indigenous ontologies and intelligence.

HG: Tell me more about how Mende ontology opened your eyes and liberated your mind to different ways of experiencing the body?

ADF: One example is respecting and caring for your body is embedded in the culture. The idea of a hierarchy based on body type is not something that is focused on. Therefore, the aging body is honored and not frowned upon.

HG: What are you working on now?

ADF: I am working on my first monograph, and I am very excited about that. Also, I just released a hand-bound zine called, Hala: an unexpected gift. This zine is a collaboration between myself and another artist who I’ve always wanted to exhibit with. The zine is a documentation of our conversations and our works sharing space. This first issue features interdisciplinary artist Orlee Malka. I plan to release two to three of these a year. I am also making some new works for upcoming exhibitions. I have a solo show coming up at The Penumbra Foundation that I am excited about. I am also teaching and give frequent guest lectures, so I’m quite busy these days.

HG: Where can people find your zine?

ADF: My zine is available at https://adamadelphinefawundu.bigcartel.com/

HG: Thank you for your time and for sharing your work!

All images © Adama Delphine Fawundu