Q&A: Aldeide Delgado

By Rafael Soldi | December 18, 2020

Aldeide Delgado is a Cuban-born, Miami-based independent Latinx curator, and founder & director of Women Photographers International Archive (WOPHA). The organization researches, promotes, and educates about the role of women, and those identified as women in photography. Delgado was recently awarded grant from the John S. and James L Knight Foundation to produce the 2021 WOPHA Congress at Perez Art Museum Miami (PAMM). She is the author of the online archive Catalog of Cuban Women Photographers, as well as the namesake ongoing book. Her interests include gender and feminism, racial identity, photography and abstraction in visual arts. Publications, where she has contributed, include Cuban Art News, Artishock, Terremoto, C&America Latina, Arcadia, as well as diverse independent art blogs. She writes for Artishock, Terremoto, ArtNexus, and C&America Latina.

Rafael Soldi: What's your background? How did you start your career and what themes does your research encompass today?

Aldeide Delgado: I am an art historian. I studied Art History at the University of Havana from 2011 to 2016, where I specialized in the history of Cuban photography. At this time in the academy only 1.8% of theses submitted for bachelor’s degrees in Art History and of dissertations presented for PhDs in Art Sciences were dedicated to photography (as opposed to other major fields of artistic production—such as Visual Arts, Audiovisual Arts, Architecture and Urbanism, etc.—in which most students were focusing their research). For me it was important to understand how the history of Cuban photography has been institutionally defined through the gaze of male photojournalists associated with the political agenda of the government and aligned with the populist values of post-1959 Cuba. Also, the lack of recognition paid by scholars to women’s artistic practices was made evident to me. I remember a teacher once mentioned that a characteristic signature of the Cuban art scene during the 1990s was the rising number of women artists. It sparked my attention. I asked myself, where are the other women in this history? One of the arguments I often heard was that there were no women in photography, or that if there were, they were no good. These conditions propelled me to organize the Catalog of Cuban Women Photographers, a project which spans artists from the 19th century through the present.

While at the beginning I focused on Cuban women photographers who inhabited the specific context of the island, when I moved to Miami in 2016 the need to expand the project was confirmed for me. The scope of the work needed to grow beyond the Catalog, to create an ongoing initiative that could offer a space, a platform that could provide greater visibility for the stories of these overlooked artists. This is how my interest in pursuing a re-reading of the history of photography from a feminist and decolonial perspective began. This work, informed by the notion of curatorial practice as an activist endeavor, is also a result of my personal experience.

RS: Tell me about Women Photographers International Archive (WOPHA). What does WOPHA do, and what projects is the organization working on right now?

AD: Women Photographers International Archive (WOPHA) emerged after working with the Catalog of Cuban Women Photographers for five years. I created the organization to expand the approach of the original project. Living in Miami, I didn't want to be that Cuban curator who only worked with Cuban artists; for me it was so important to embrace the multicultural character of the city. Thus, the organization has a strong focus on historical research, producing rigorous academic texts on artistic production from Latin American and Latinx communities. We preserve primary source materials related to women and photography, offer reference services to individuals and institutions to assist with long-term studies, curate exhibitions—online and in-person—produce catalogs and organize scholarly symposiums and lectures.

We created an electronic database wherein you can find a portfolio of each artist with their biography and their artist statement listed. The idea is to have a wide database where people—academics, students, curators and critics—can access information on all of these women photographers. In collaboration with other organizations, we also offer studio space to artists and photography-based workshops. Currently, we are partnered with Faena Art here in Miami to award a three-month residency and exhibition space to Miami-based, Belizean-US photographer Amanda Bradley.

RS: Just like Strange Fire, WOPHA exists primarily in a virtual space with occasional in-person programs, exhibitions, and the like. And we have found that this allows us to be very nimble and flexible. What kind of opportunities do you think this format offers to an ambitious grassroots project like yours?

AD: The first opportunity it offers is to re-imagine the idea of the archive. I decided to create an archive because archival spaces have historically worked as violent repositories for the validation of imperial history. In this case, for me, it was crucial to use the structure of the archive as a space for legitimizing women artists’ works. Now the other concern is who has access to archives, what kinds of images are shown in the archive. Of course, there are always restrictions but accessibility is one of the main benefits of a web-based format for us.

RS: Absolutely. I sometimes struggle with the idea of using the word archive—and we often refer to Strange Fire as an archive—knowing just how effective a tool for colonization the archive has been. At the same time, we feel the need to take ownership of the archive and reimagine what it looks like.

AD: Exactly. One question we usually get is, what does this archive look like? Do you have a physical presence? Do you collect work? That's not the case. All the works are held by the artists, we don't preserve actual artworks. But we do keep an archive of printed matter that's available to the public. And through my curatorial process with WOPHA, I constantly advocate for exhibiting and opening the archive to a variety of voices.

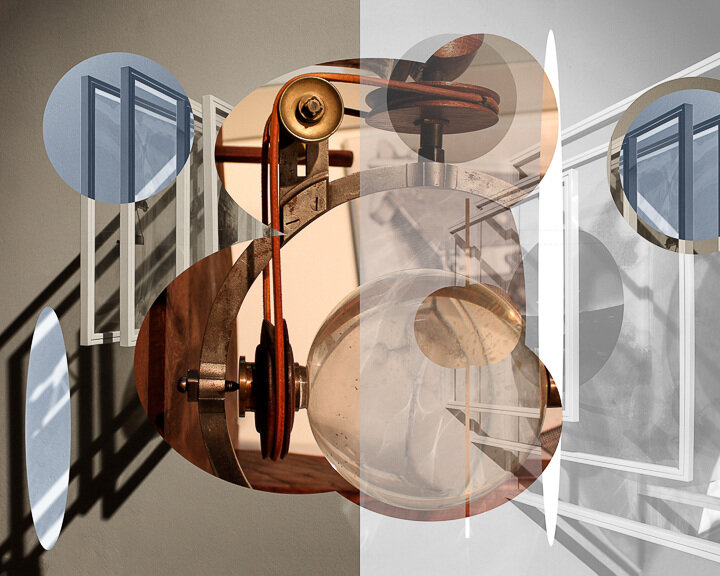

RS: I want to go back to something you said earlier when you were talking about your introduction to Cuban photography. I'm interested in your thesis—I read this in one of your essays—that contemporary Cuban photography often falls on these two predominant camps. Documentary and conceptual photography. And these seemingly opposite approaches, one of which is purely objective and one of which is purely subjective, can coexist both in harmony and in discord. And of course, the idea that photography is inherently truthful or objective is questionable. We know that. But can you expand a little more on how these ideas played out in your exhibition "Landscape o Miradas al entorno"

AD: I’m grateful you’re bringing up this memory. ‘Miradas al entorno’ was one of my first curatorial projects; I was still a student at that time. That exhibition was part of a series of experimental essays attempting to identify some of the stories that women photographers were exploring then. My first efforts were to locate women photographers in the Cuban context and to identify the main topics they had been working on. In opposition to pretentious post-1959 institutional photographic discourse, the artists in the show were approaching the urban and natural space in a very intimate way that subverted both the documentary and social significance of the image. I specifically reject these kinds of categorizations of photography in terms of documentary/objective and conceptual because all these genres are connected and, indeed, they are not pure anymore —I’m thinking of pure photography as defined by the West Coast’s Group f/64 in the early 20th century. There’s the misguided belief that documentary photography is an objective representation of “reality”, that documentary photography is capable of showing “truth”, but we know that speaking about “reality” and “truth” is totally inaccurate. In fact, the photographer is bringing all their ideology and subjectivity in the act of representation. In this project I was more focused on how different artists were using photography to deconstruct their environment, how they were looking around themselves.

RS: And jumping forward now to some of the projects you're working on today, some of your recent research has been around understanding and defining the label "Latinx", which is generally considered appropriate and inclusive as we speak today in 2020, but may very well be outdated in the future. How did you become interested in this topic and what can you tell us about what Latinx stands for?

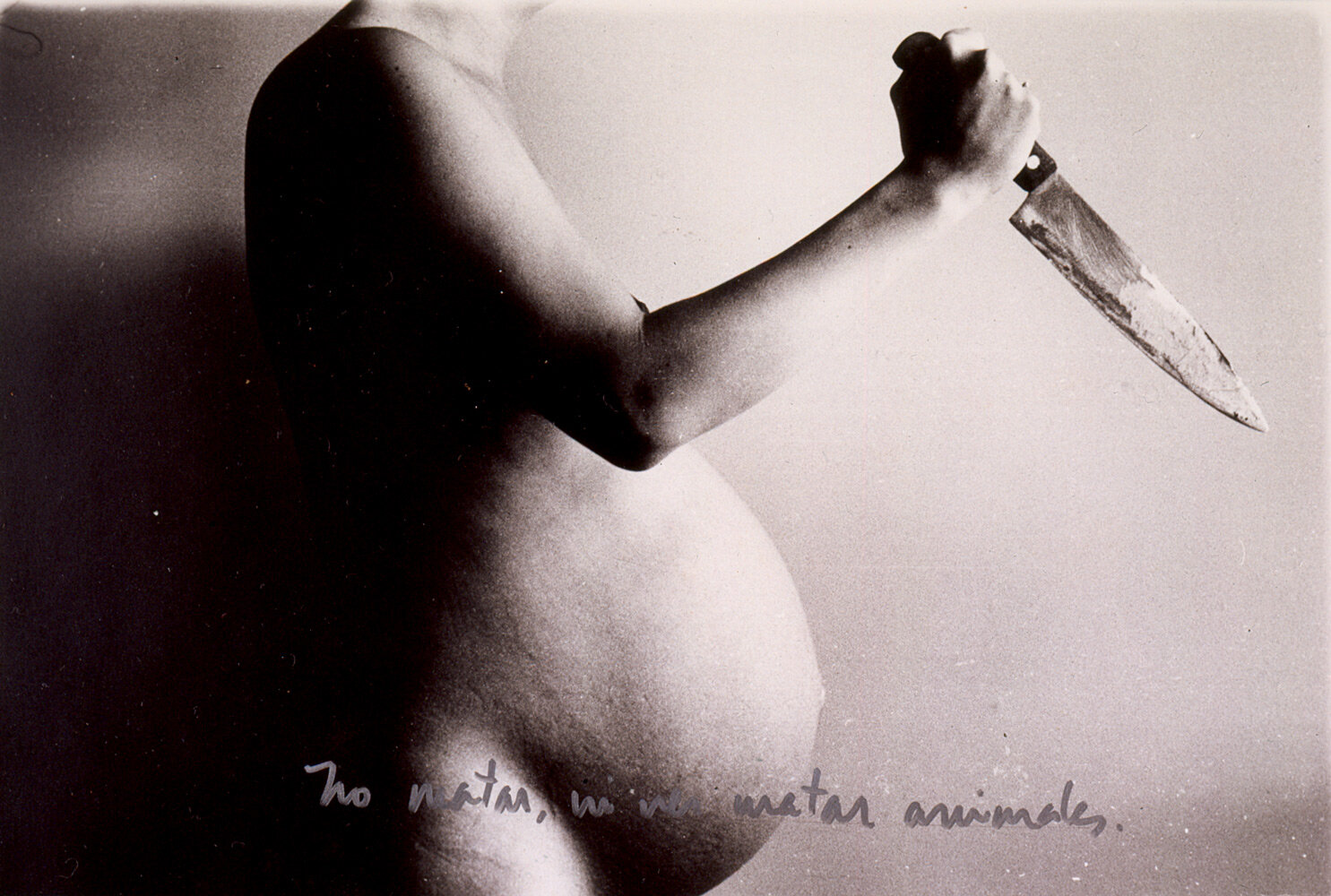

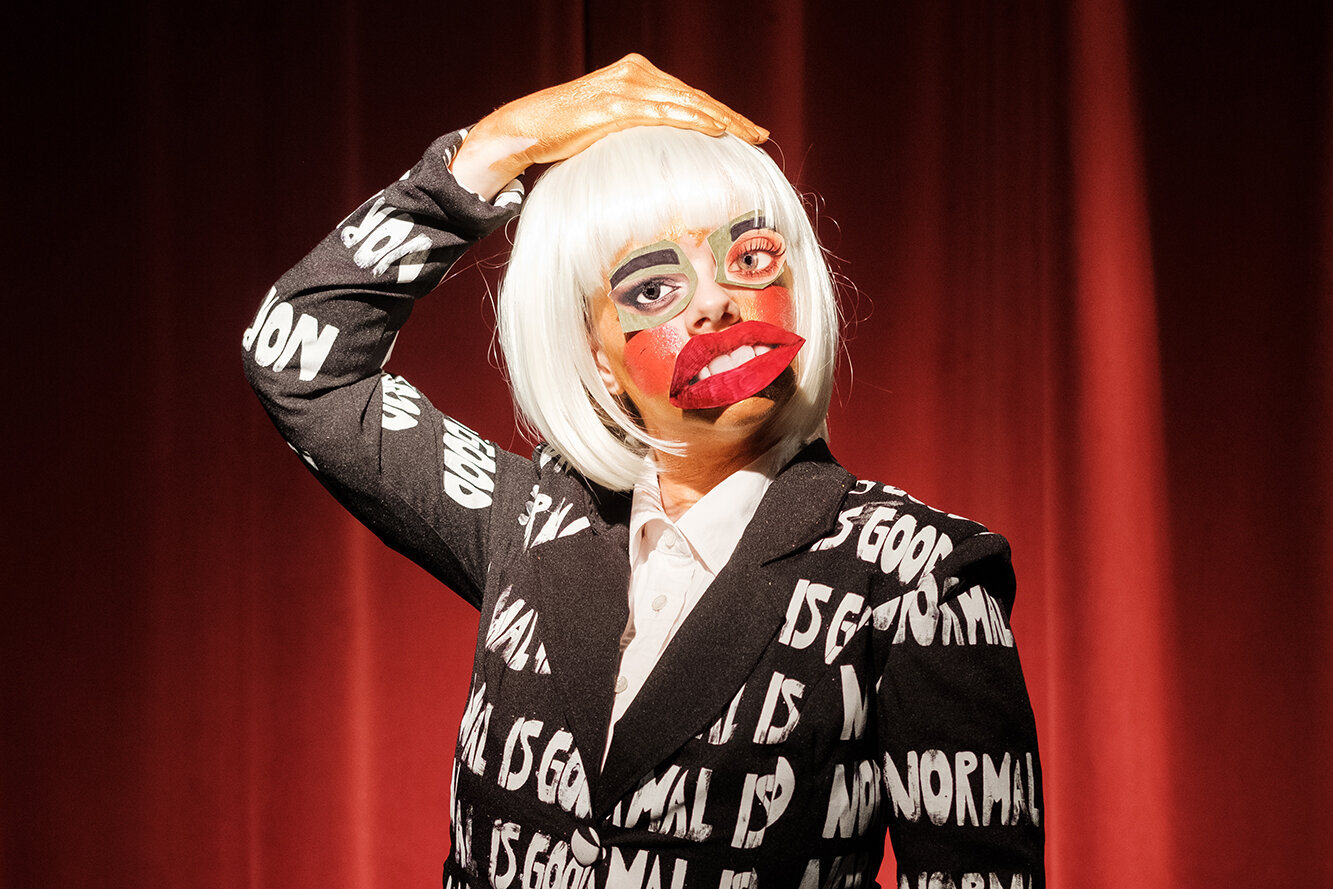

AD: I became interested in the topic of Latinx through my experience of living in Miami. I remember the first time that I read about this term was in the catalog of the exhibition "Radical Women: Latin American Art'', presented at the Hammer Museum during the Pacific Standard Time: LA/LA initiative in 2017. In the catalog, the curators indicated that they didn't include the term Latinx because it wasn't part of the discussion or vocabulary during the timeframe that the show covered—the 60s, 70s, and 80s. So that was my first encounter with the topic. Then here the Pérez Art Museum Miami organized the Latinx Art Sessions, in which I participated as an adviser. At that same time, I was trying to carve out a space for myself in an evolving scenario in which I am no longer 100% Cuban nor have I become 100% US-American. So "Latinx'' offered me that liminal space in between the two nationalities that I like and that I am embracing now—the space of the border. Speaking with different artists with whom I work, I’ve discovered this is a process they've been dealing with for a long time. For example, artists Nereida García Ferraz, Juana Valdés, and Yali Romagoza, who I included in the exhibition "Building a Feminist Archive: Cuban Women Photographers in the U.S." The exhibition specifically took the frame of Latinx to include the experiences of Cuban women artists working in the U.S. since the 70s.

I became interested in Latinx specifically as a result of my need to occupy a space in the context of a migrant person, that context in which I don’t fully identify with categorizations such as Cuban art, Caribbean art, Latin American Art, African American Art. I intersect all of them, and taking this experience as a reference point, I try to define Miami as a place for the production of knowledge in a border space.

RS: Across the decades, there has been a cultural and linguistic evolution around labels, both here in the U.S. and in Latin America. What story do you think this evolution tells? What does it tell us about how Latinx people are perceived by others and by themselves?

AD: The main thing with categories is how malleable they are- they’re not natural, they are constructed. We need to use them and appropriate them as political tools for reclaiming our rights, demanding better conditions, better opportunities. We can use these labels as a tool to fight institutional and structural racism, or we can provoke a more justice-oriented agenda within the different spaces in which we are.

You see how Latinx, for example, finds its linguistic reference in the category of Hispanic, in the Latino category, then in the Latina/Latine/Latino, all these options. For me, these new categories are about how in the end we need to adapt to our society. There's a lot of conflict with the term Latinx because some people defend the “purity” of the Spanish language (you can follow some of this discussion in the conference talk “What is Latinx” that I presented at the 1-54 Contemporary African Art Fair this past fall). For me, it's more about how we create diverse spaces—and I will support initiatives that allow me to create spaces of visibility for marginalized identities. The evolution of these terms evidences how these are political tools that we need to use to our benefit.

RS: So you mentioned some opposition. What are some of the limitations or criticisms that the term Latinx has received?

AD: One of the main critiques of the term has been what we can call linguistic limitations. Who is included in Latinx and who isn't? For some people, Latinx just perpetuates this stereotypical representation of Latinx identity as a monolith and doesn't necessarily consider the plural conditions that people from Latin America experience. So that's the main difficulty—how do we represent the immense diversity of Latinx culture, for example, the Asian, African, and European identities within Latin America? But, more importantly, how do we represent how all these cultures collided in Latin America through the process of colonization? So, when we say Latinx, we can't assume that we are speaking of a single or monolithic identity, but rather we need to think of this identity as the result of that mix of cultural experiences. Another critique of the term is that, if we're aiming to decolonize the Hispanic or Latino term, why are we not choosing a term that represents the indigenous history of Latin America? California activist Motecuzoma Sanchez asks why we don’t adopt a gender-neutral indigenous language such as Nahuatl or Purepecha. We may agree that it's a complex process of analysis, and each person must make a decision as to how to self-identify. I don't consider Latinx as something that you need to impose on everyone, but it needs to be wielded in response to how you imagine your place in the world.

RS: I'm sure you've spoken to so many artists, and you have your own experience, too. I consider myself Peruvian. I am Peruvian. I was born there. I was raised there. But I've struggled to understand that I am no longer just Peruvian. I am Peruvian living in the United States, and that has to be a part of my identity, whether I want it or not. And when I go back to Peru, I am not like everybody else. You know, my accent is now a little bit different. My experience is very different from my friends who still live there, and it's been really hard to accept that identity. And I’ve had to learn to embrace and understand that I am Latino in a different way now than I was the first half of my life. It’s complicated.

[Here the interview switches to Spanish language. English translation by Rafael Soldi]

AD: It’s complicated because, look, right now I’m talking to you in Spanish and I’m having to do the same exercise but in reverse. When we talk about identities, for example, and I have to talk about my practice, sometimes I don’t actually know which language will be easier for me. We find ourselves in this space between two languages and two contexts. And obviously this is not new nor exclusive to the Latinx identity.

One of the artists I work with, Carlotta Boettcher, her parents are Germans who immigrated to Cuba in the 40s. She then came to Miami, then lived in Spain, France, and later San Francisco and New Mexico. She now lives in Guatemala. So, what is the sum of all the experiences that this person carries with her? And how are we going to categorize her, or how is she going to identify herself? To me, that is up to the artist- but as curators we’re always trying to categorize.

In a text I am currently writing, I talk about these nation-centric perspectives where we are always trying to categorize a person into a single identity, and that is the first thing we should question. That’s the biggest issue with Latinx. Sometimes these strategies of categorization cast too wide a net. All of us who are advocating for Latinx Studies tend to stretch the concept as much as possible. But what’s important to me is to recognize that it is a political strategy and that’s why I like how Arlene Dávila talks about Latinx as a project and not an identity. And within this idea of the project, she talks about how perhaps in the future we may not even need the term anymore. Much like with the “women” category.

RS: Exactly. We never say "men artists" we say artists and "women artists".

AlD: And there are feminist perspectives that propose that the term “women” as a category will eventually cease to exist. But so long as we are within that colonial and patriarchal matrix of knowledge and power, it’s important to continue this work.

RS: What can you tell us about the state of Cuban art today and what are some of the challenges still to overcome? And what do you celebrate?

AD: I can't answer this question without addressing what is happening right now in Cuba. I am referring to the severe censorship and repression of artists reinforced by the implementation of the Decreto 349, which is a regulatory measure established by the government to criminalize independent art production within the island. Over the last few days (this interview was conducted on Dec. 7, 2020), approximately 15 people from different backgrounds, led by visual artist Luis Manuel Otero Alcántara, went on a hunger strike to protest the unjust imprisonment of a musician. What's happening with Cuban art is something that has been escalating more and more since the most recent Biennale. There have been a series of public dialogues led by artists who are demanding freedom of expression in Cuba. So truly, there is nothing more important than this right now as it relates to Cuban art, this demand for freedom that artists are exercising. It's hard to find something to celebrate at this moment. This goes beyond artistic production, it's about the overwhelming levels of confinement and poverty that the Cuban people are experiencing at the hands of a broken government that has held power for over 60 years.

RS: Yes. It's a very complicated situation and your answer to my question must reflect the severity of the moment. What are you working on right now and how can we follow your upcoming projects?

AD: At the moment I have two projects that I am excited about. The first one is research on women photographers from the Dominican Republic, in partnership with the Centro Leon. It will be the first research project focused on women photographers of that nation. (For me, it's also important to note that when I say women, I am also referring to trans, queer, and non-binary artists.) The second project is the upcoming WOPHA Congress at the Perez Art Museum Miami in November 2021. The WOPHA Congress seeks to be the first international gathering of organizations dedicated to photography, feminism, gender, and women and will convene art historians, curators, artists, and writers who've been working at the intersection of women, photography, and feminism. It will be a two-day symposium at the museum accompanied by parallel activities throughout the city.

RS: It sounds like you have your hands full.

AD:Definitely. In preparation for the Congress, we've been hosting small focus groups with similar organizations to Strange Fire, to understand and identify topics that each participating group deems critical right now.

RS: I definitely feel that there is an important dialogue coming right now from these grassroots efforts led by independent curators, artists, and organizers. These platforms that are not linked to institutions and are not liable to boards and donors are providing critical and timely discourse right now. We are able to pivot and adapt more quickly to the rapidly changing moment.

AD: Sometimes I’m asked how I imagine my practice, or that of WOPHA in relation to other institutions. I always like to mention the idea of contamination. We talk about how we have to challenge institutions and create new content narratives. So, departing from exercises in contamination we can create changes in programming and in the agendas of these spaces.

RS: I like your analogy of contamination. We've had a lot of similar conversations but thinking in terms of intervention. Particularly right now, staging an intervention on academia and how art is taught in schools.

AD: Yes and specifically how photography is taught—it's horrible! I've recently had a closer look at how this medium is taught here in the U.S., because of the work I’ve been doing. And truly, it's so important to penetrate these spaces with new analytic perspectives, new knowledge. Many spaces today have already adopted a basic decolonial perspective, or a perspective of gender equity—but academia is not quite there.

RS: And similarly, photography is taught in a very isolated manner. It exists solely in the context of the history of photography. There is very little interaction with other genres and modes of production, which is unfortunate and a handicap to young artists coming out of these programs. As if photography just had a parallel history to the history of art, but those histories never collided.

AD: Absolutely, or as if photography can't function within the larger art context. I love photography because it's always pushing against a limit, there is so much to uncover.

RS: And the fact that it's such a young medium I think brings a lot of opportunity to mold its future. Thank you so much Aldeide, we're so glad you could chat with us today.

AD: Thank you Rafael.