Q&A: Aline Smithson

By Hamidah Glasgow | October 21, 2021

Aline Smithson

Aline Smithson is a visual artist, educator, and editor based in Los Angeles, California. Best known for her conceptual portraiture and a practice that uses humor and pathos to explore the performative potential of photography. Growing up in the shadow of Hollywood, her work is influenced by the elevated unreal. She received a BA in art from the University of California at Santa Barbara and was accepted into the College of Creative Studies, studying under artists such as William Wegman, Allen Ruppersburg, and Charles Garabian. After a decade-long career as a New York Fashion Editor, Aline returned to Los Angeles and to her own artistic practice.

She has exhibited widely including over 40 solo shows at institutions such as the Griffin Museum of Photography, the Santa Barbara Museum of Art, the Fort Collins Museum of Contemporary Art, the San Jose Art Museum, the Shanghai, Lishui, and Pingyqo Festivals in China, The Rayko Photo Center in San Francisco, the Center of Fine Art Photography in Colorado, the Tagomago Gallery in Barcelona and Paris, and the Verve Gallery in Santa Fe. In addition, her work is held in a number of public collections and her photographs have been featured in publications including The New York Times, The New Yorker, PDN, Communication Arts, Eyemazing, Real Simple, Los Angeles, Visura, Shots, Pozytyw, and Silvershotz magazines.

In 2007, Aline founded LENSCRATCH, a photography journal that celebrates a different contemporary photographer each day.

HG: Aline, you are a gift to the photography community with your artistic talent and the seemingly unending resource of the daily Lenscratch. Where do you find the inspiration for your work and to keep Lenscratch current?

AS: I hardly feel like a gift…lately, more like that damaged box that needs to be sent back to Fed Ex. Honestly, I am on overload a lot of the time—between teaching, Lenscratch, saying yes to too many things, and struggling to clear time to make my own work, it’s a constant battle.

In terms of my own work, inspiration doesn’t seem to be difficult. I have many projects percolating, and creating work is never an issue. I straddle working in a conceptual way with photographing my world and life. For me, it helps that I come from an art education background, so I think of photography as just another tool to make art or tell stories.

Lenscratch is all about inspiration (and community). It’s such a privilege to share the work of photographers who are thinking deeply about their projects with imagery that continues to excite and elevate. My favorite time of year is in May, when we go through all the amazing work that students are creating. The Lenscratch Student Prize is always an inspiration and a great way to gauge what’s next.

Whenever I consider pulling the plug on Lenscratch, I think about all the work I wouldn’t see or photographers we couldn’t support. It never fails that when I’m feeling overwhelmed by it all, I’ll get an e-mail from an educator or photographer telling me how much the site means to them. I’m proud that we all (our incredible editors) work for free, have no barriers for entry, and just want to celebrate others. I have always felt the site should feel like a community, and hopefully, it does.

HG: It does feel like a community. I admire how you have built a team of people dedicated to helping photographers get their work out to a larger audience. It’s also important that the group has such a broad focus that it is inclusive and available to anyone with an internet connection. The barriers to access are very low for Lenscratch, which is remarkable in our industry that generally has pretty high barriers. Photography is a rich person’s playground for the most part. Is that how you envisioned the site when you first created Lenscratch?

AS: I didn’t have a specific vision for the site when I started -other than to learn about photographers. Fifteen years ago, it was the era of the personal blog. A friend suggested I start one, and after a few months, it felt like a completely hollow effort asking all five followers to like my posts…it was not dissimilar to how Instagram is today, but with a lot more words! I was teaching and realized I could create a platform to learn and also invite my students to learn along with me. For the first couple of years, I just wrote about artists who I found interesting, without contacting them—just pulling work off their site. Then I began to reach out and ask permission, and for better files, a statement, and a bio, and I started connecting to photographers in a more profound way.

The site keeps evolving—since we all work for free, I’ve had some incredible interns who needed to step away to make a living. Over the last two years, I have brought on about ten new editors who help take the burden of writing off of me and knowing it’s important to broaden our reach and have more diversity. We now have editors from around the globe and editors from diverse backgrounds. The point of the site is not to critique work, but to say, “look at this cool work.” And most importantly, I wanted to create a site for educators and students, with areas on the site to search genres, subjects, processes, etc. The more voices and contributors, the better.

HG: It is uncommon for people to sit on both sides of the review table to participate in and curate exhibitions. I believe that this gives you unique perspectives of the photo world. Would you share some of your insight with us?

AS: I am always trying to deconstruct the photography world and understand what makes a successful project, then again, I am always redefining success itself. By having a window into what a curator, publisher, editor, or gallerist might be looking for, I begin to appreciate why certain artists rise to the top. Certainly, this perspective is helpful in my teaching as I pass on what I’ve observed or learned. It’s so important to bring a level of excellence to all that you do—not only with the work but everything that surrounds it. Thinking critically and conceptually, writing well, considering dynamic installation ideas, and being thoughtful and kind all count. Artists also need to slow down and spend a good amount of time considering and creating work before releasing it. The project only gets richer with the patina of time.

HG: I suspect that it is the service aspect of your work that you continue to teach, mentor, and contribute to the photo world in other ways than your work. I hear you say that you want to carve out more time for your work, but you are always taking on new projects that take time away from your work. Tell me about that dynamic.

AS: It’s not a good one. I am most fulfilled by making work…even having an hour to revisit old images makes me happy….and unfortunately, I have to put XX’s on days dedicated to my own work. I remember long ago Keith Carter saying that most of his work was made on his trips to various locations, and I was startled to think he wasn’t making work all the time. As I’ve gotten farther down the path and have created numerous projects, I’m not as worried about a finish line and producing a lot of work quickly. But I am starting to say no to things. My family has been encouraging me to do that for a long time!

HG: How/Where do you see the photo world adapting to the new realities of pandemic programming, post-pandemic programming (if there is a post-pandemic – perhaps Covid will become endemic), and the racial reckoning that took front and center in 2020 and continues to evolve how organizations operate?

AS: The pandemic has shifted things profoundly. With the advent of ZOOM and every photo organization expanding their reach and programming, we are much more connected. But because of that, we may need to push back on so much time in front of the screen – and therefore, the audiences will become smaller. As artists, the pandemic made us turn inward and reassess our lives and tell our stories. I certainly pushed the reset button on my priorities and figured out what was important to me on this journey.

The racial reckoning was long overdue, and many institutions and organizations are now (finally) celebrating artists of color. There is so much profound and important work being made, and our community is so much richer with voices of color.

HG: How has your work evolved over the last year and a half?

AS: I create a lot in my head…I think about a project for a long time before I create it. A new series emerged from the loss of a hard drive during the pandemic, and after I got over the shock, I saw it as an opportunity to make art. I don’t think my work evolved necessarily as I continue to explore similar themes, but I loved having time to play and experiment with captured and vernacular photographs, to begin a small book of personal stories, and to consider new ways of working.

HG: What piece of advice do you give to people starting out on a photographic path?

AS: Stay anonymous for as long as possible—when you have no audience, no pressure to create, it is a joyful time of mistake-making, and in some ways, self-discovery. Create art out of failure. Be authentic. Celebrate others as the journey is so much richer with friends.

HG: Who is your favorite photo-based artist right now, today?

AS: I’m a bit obsessed with Todd Gray’s work—his installations are incredible and bring to mind everything that I love about John Baldessari but mixed with important subject matter, including cultural iconography and examinations of racial identity. (https://www.toddgrayart.com/)

HG: The trajectory of your work is quite varied, and you’ve been experimenting a lot in the last several years. I am particularly fond of the Fugue State work. Tell me about that work, the inspiration behind it, and where you are going with it now?

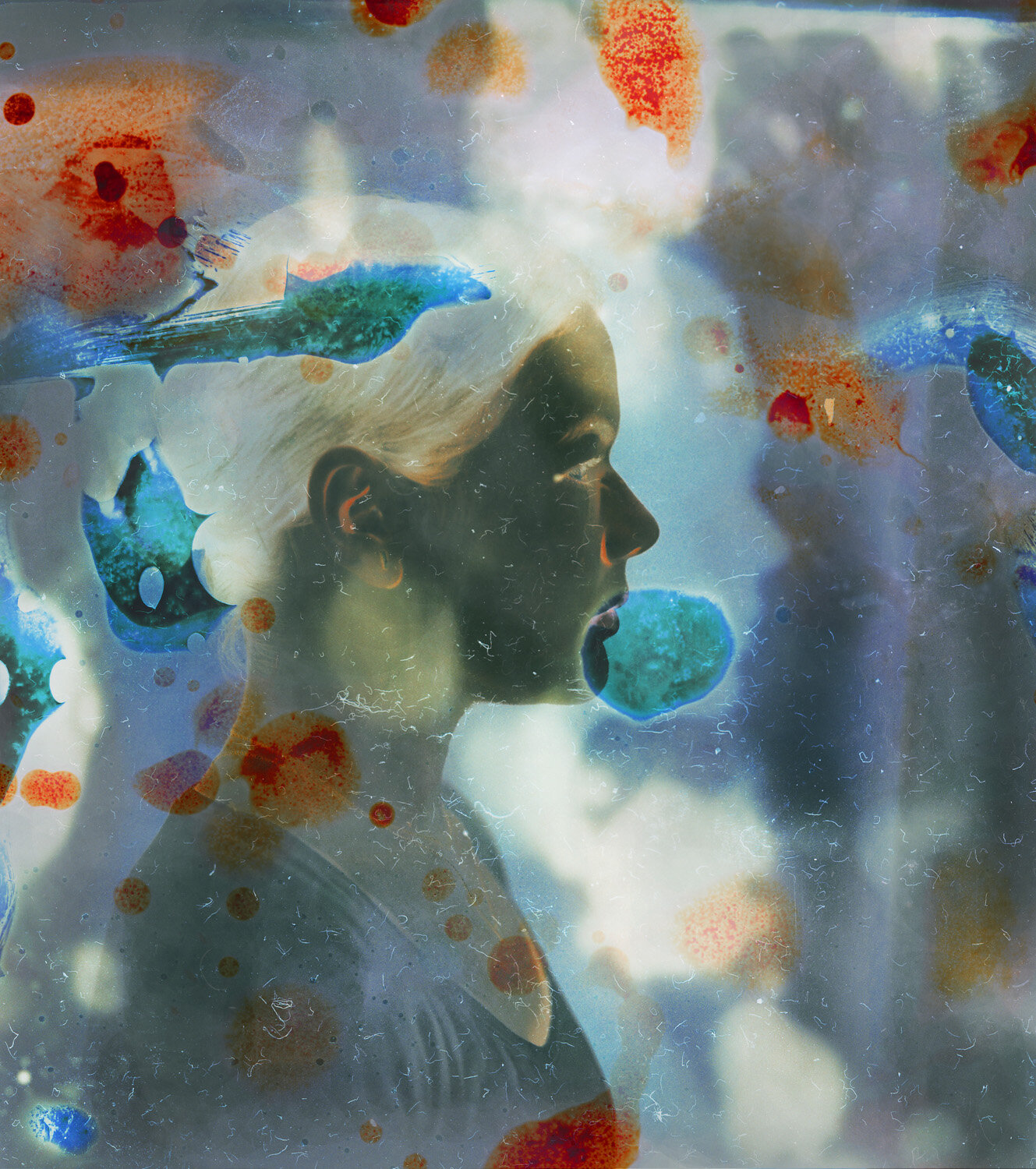

AS: When I was in art school, I experimented with everything; for the most part, I was a painter of large abstract oils, but also created monographs, lithographs, etchings, drawings, photos, and even zines. When I came to photography, I was pulled into classical thinking, but with a bit of humor on the side. Since I work with film and classic cameras, my work tended to be more formal and thought out. In 2007, when I started the Shadows and Stains series, I felt like I was reconnecting with my artist self, and the work echoed my work as a painter….it opened the door to experimentation again.

When I discovered work that was more process-based, work that uses process to elevate the story behind the work, I was immediately intrigued and excited. Fugue State marked my foray into that territory. It was thrilling to have no control over the results. The idea of process aligning and elevating subject matter doesn’t work with everybody of photographs unless that is the focus of your practice like Matthew Brandt, Odette England, or Meghan Rieppenhoff, but it’s an idea that I am again using in my most recent series, Fugue State Revisited, and will continue to execute when it works. As we both know, the photo world has exploded into whole new ways of using and creating photographs in unique ways to tell stories.

From Embarrassment Of Being Human Series

HG: Tell me about the Embarrassment of Being Human work?

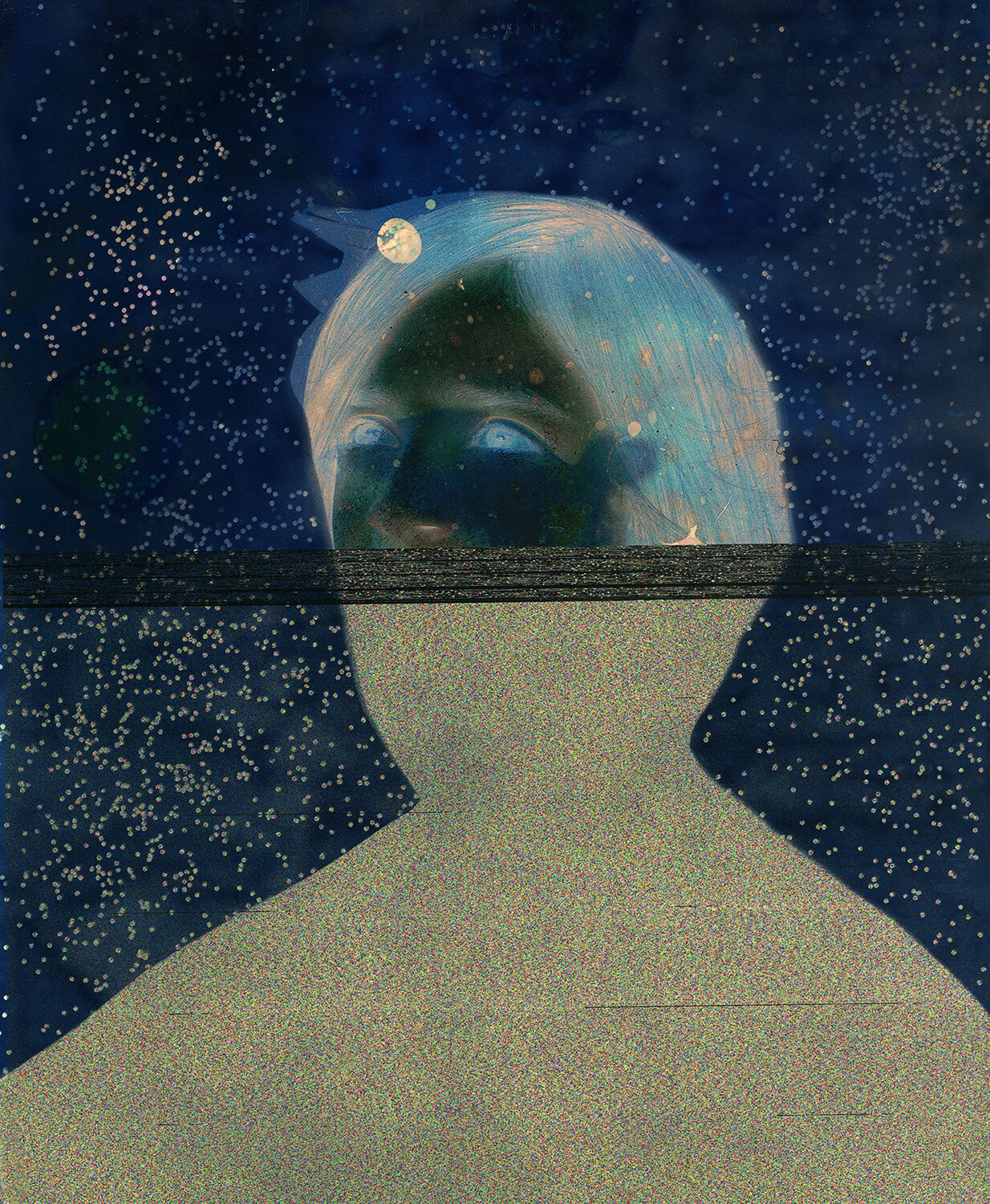

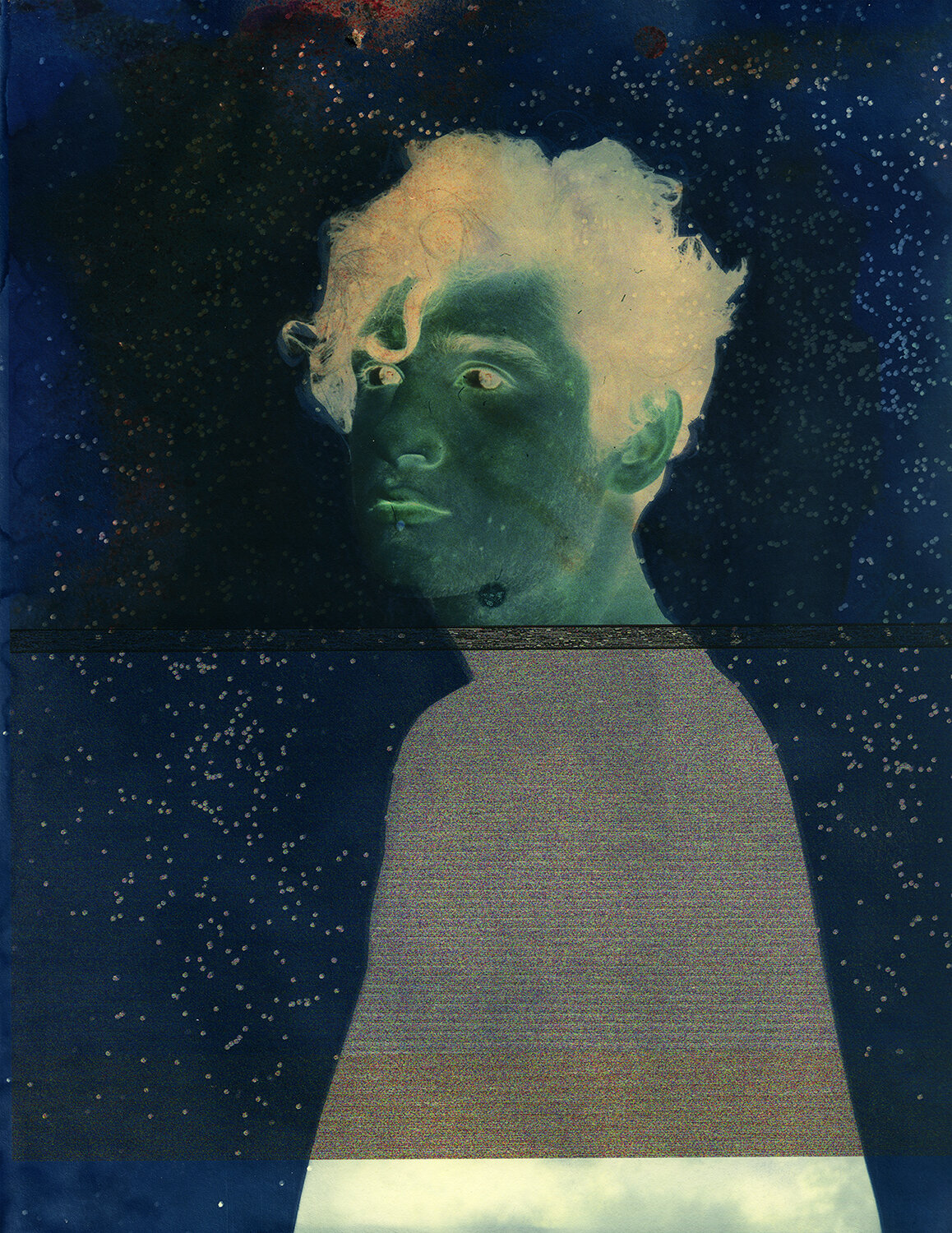

AS: The Embarrassment of Being Human considers mortality by examining our private discomforts and the detachment that humans have with their most primal self. Presented in a way that allows for examination of who we are, the photographs explore the disconnect between our physical and mental selves. By offering up the parts, secretions, and behaviors of our bodies that we would prefer to avoid making public, we are forced to acknowledge the irony of living inside a vessel that is at once miraculous and magnificent and at the same time makes us uncomfortable by the connection to our carnal self.

Over the course of history, humans have considered the physical self in a myriad of ways, not just in the reflection of the physique, but also in the mechanics of how the body operates. Societal and cultural norms define how we consider our bodies and our bodily functions, and those definitions range from acceptance to repulsion. Covered up and puritanical in nature, we in the western world have a level of embarrassment with our natural selves.

From Embarrassment Of Being Human Series

HG: I’d like to hear more about the archive you have been collecting and your plans for that work.

AS: I have been collecting photographs since I was a teenager, but I started a focused collecting of found photographs when I moved to New York after college. And by found, I mean found on the ground. I was constantly looking, and surprisingly, my collection began to grow. I would frame and covet these lowly, often dirty and damaged images—drug store photographs, school photos, polaroids that somehow had slipped out of someone’s hands. I felt like I was collecting secrets. My best find was in Los Angeles when I found a strip of negatives on the ground. When I got the prints back from the lab, I was thrilled by what was revealed—a very stoned young man with red eyes, snorting coke off a framed photograph of his parents. SCORE! I also once picked up some torn-up photographs covered in vomit that I found on one of my walks, much to my children’s disgust.

I began to collect more formal portraits at flea markets and thrift stores and created the projects, People I Don’t Know, But it was after seeing the amazing exhibition, Secondhand (https://pier24.org/exhibition/secondhand/), at Pier 24, that I was inspired to collect whole archives. Curator Erik Kessels’ collections in that show blew my mind. Today, so many people are searching on eBay and Etsy that it’s getting harder to whole collections. I had some wonderful luck as I was only buying negatives—something most people wouldn’t want or know what to do with.

I’d love to create a small book of one particular collection from Kansas in the 1960’s, but I am also using found photographs in conversation with my own.

HG: What is one project in your head that you haven’t started to create yet? If you are ready to share that information.

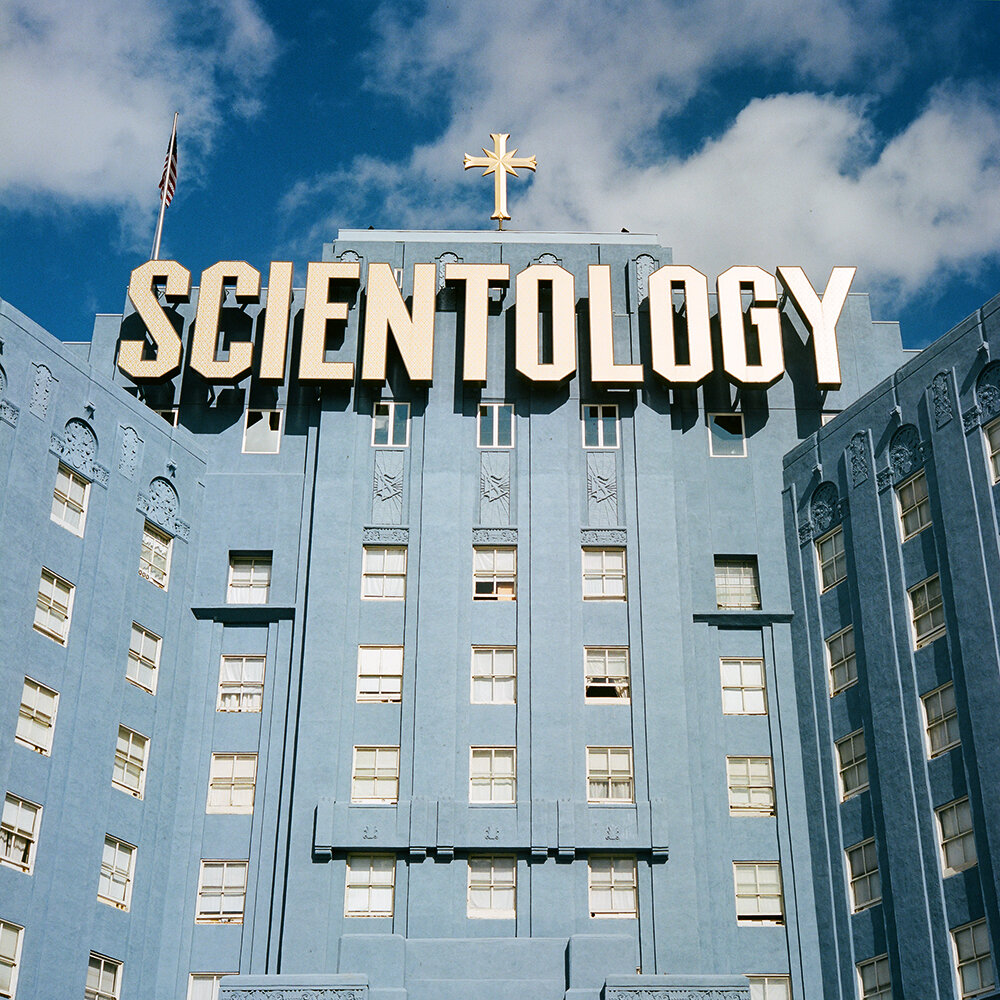

AS: I started a project a few years ago that I’d like to dig into and finish. The Mormon church charged my grandfather and great-grandfather to start the town of Eden in Arizona in the late 1800’s. My father would tell us stories about his growing up in this desolate landscape and how hard life was. My father left the church long before my parents married, so there are a lot of holes in my knowledge of those early days. My son and I went to Eden, now a ghost town, and I saw my grandparent’s graves for the first time (I never met them as they died when my father was 16). So I’d like to complete the project that circles around religion, place, memory, and ghosts.

HG: As someone with family from Utah and having been born there myself, I look forward to that work! Thank you for your time!

AS: Thank you!

From Lost: Los Angeles Series

All images © Aline Smithson