Q&A: Elizabeth M. Claffey

By Hamidah Glasgow | November 30, 2017

Elizabeth M. Claffey is an Assistant Professor of Photography at Indiana University in Bloomington. She is an honors graduate of Earlham College and has an MFA in photography from Texas Woman's University, where she also earned a Graduate Certificate in Women's Studies. She received a 2012-13 William J. Fulbright Fellowship, which she used to support her documentary and creative research in Eastern Europe. Elizabeth's work focuses on the way personal and familial narratives are shaped by interactions with both domestic and institutional structures and spaces. Her work has been recognized by PDN Magazine, Project Basho Gallery, Abecedarian Gallery, The Eddie Adams Workshop, and various other galleries and publications including The Chronicle of Higher Education, The Dallas Morning News, and The Kinsey Institute.

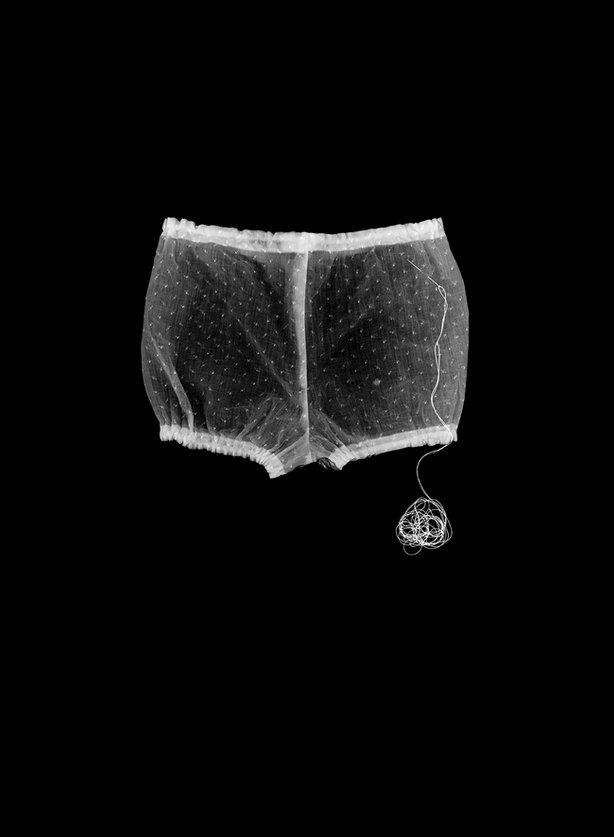

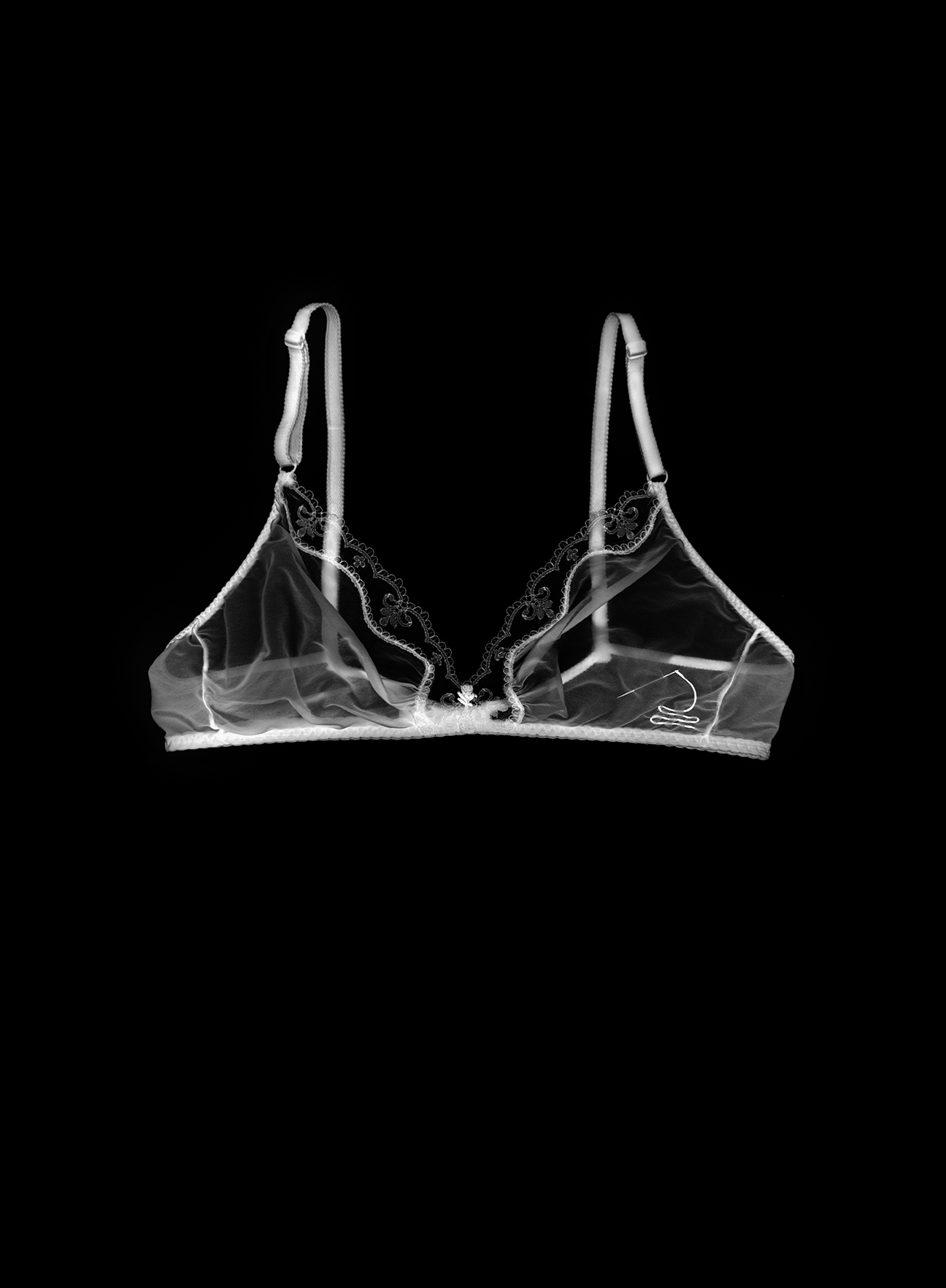

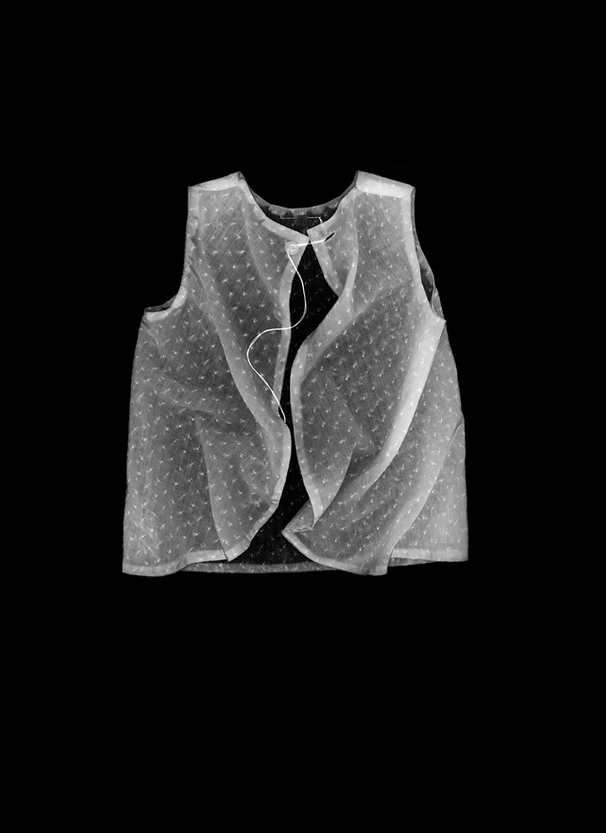

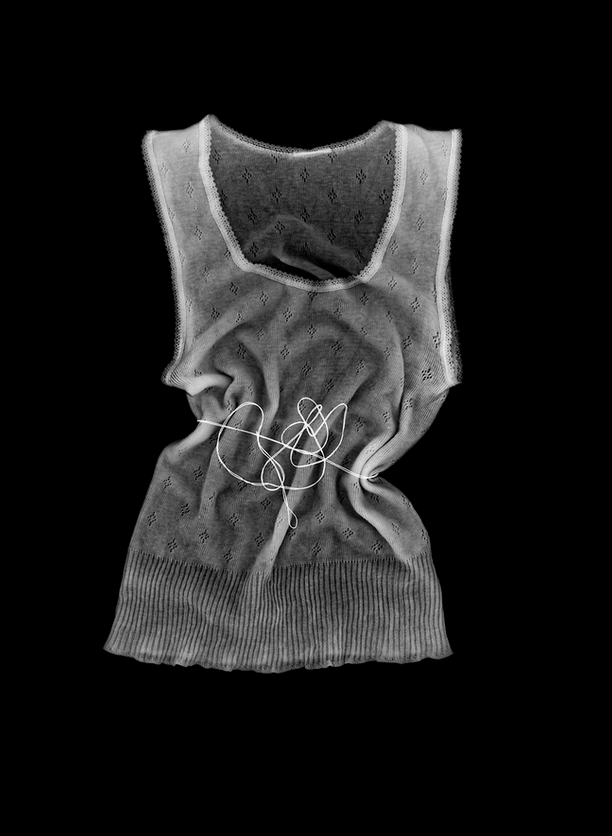

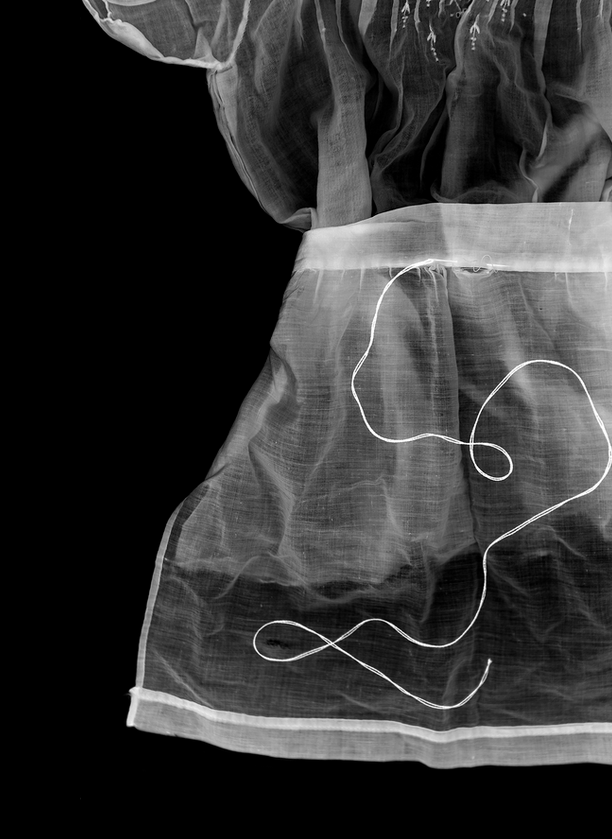

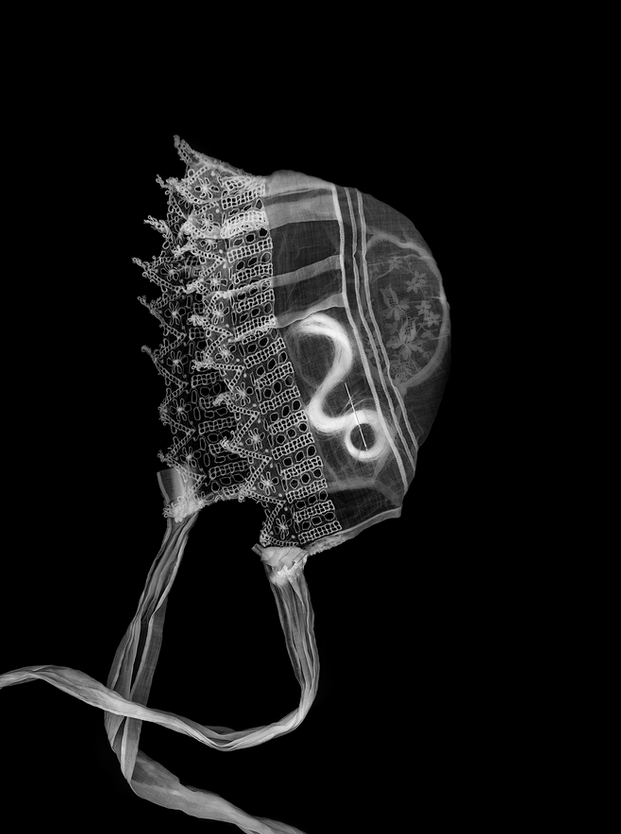

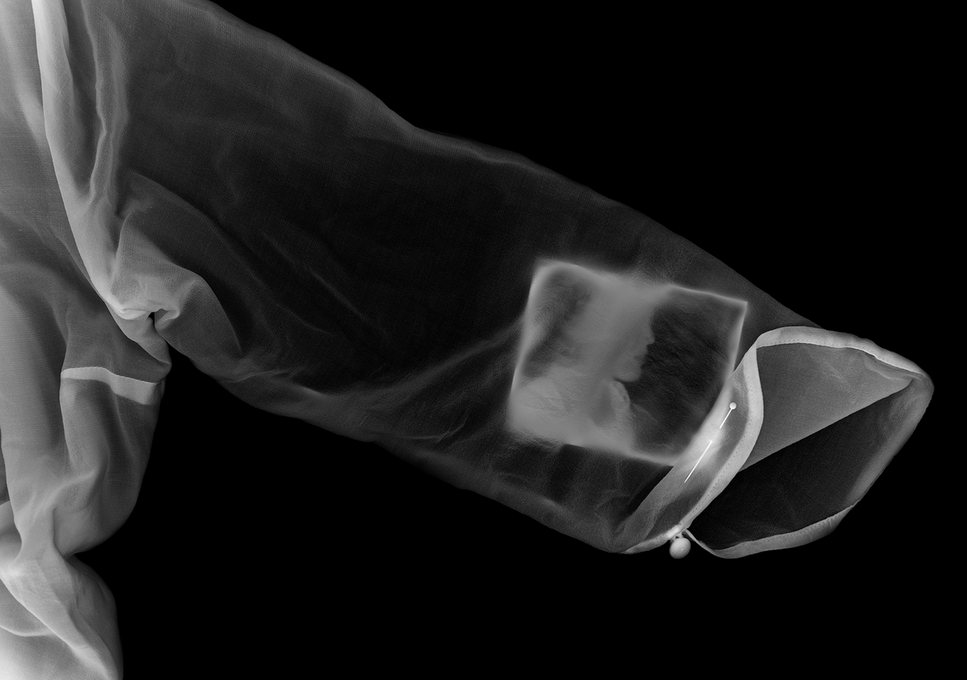

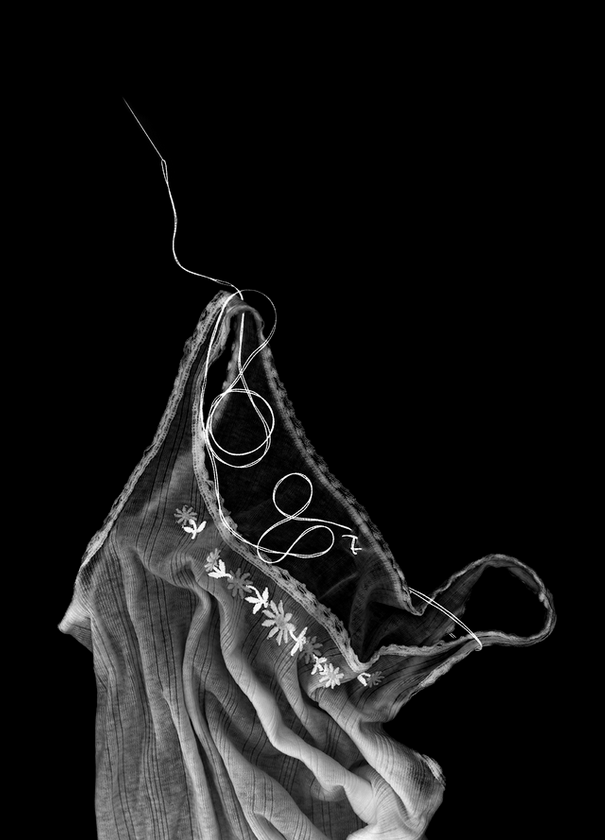

Matrilinear is an ongoing series that addresses embodied memory and its relationship to personal, familial, and cultural identity. In mainstream Western culture, public forms of power are often passed down through patriarchal lines of heritage, along with dominant historical narratives that can socially condition peoples and shape identities. However, women have often interrupted this power and conditioning through traditions of storytelling and object sharing. These images examine family folklore, ritual, and mnemonic objects passed down through generations of women. The photographs of each object reveal the physical remnants of a body long gone; including stains, tears, and loose thread from clothing that was kept close to the body for comfort and protection. The stitching and/or photographic representations are both a visualization and an expansion of stories shared as family lore. These interruptions also represent the deep influence of one’s familial past on personal identity and perceptions of the body.

HG: What prompted you to start this series? Was it a conscious decision or one that evolved over time?

EMC: The women in my family have a long-standing practice of sharing and passing down objects and clothing – including mundane things that my mother, sister, and I swap often. My partner jokes about the garbage bags of clothes that get switched from person to person when one of us discovers we never wear the items in it. I am always hesitant to discard things and at some point, ended up with several of my grandmother’s old undershirts… they ranged from girlish shirts with flower patterns to baggier, silk v-necks that wouldn’t itch her skin as she got older. Perhaps one of the most meaningful is the last one she wore before her death, which still has her surname scrawled into the neckline. My mother grew up during a time when clothing was precious, often handmade, and something that you mended until completely thread bare. That perspective was passed down to my sister and me, as we keep our clothes until they fall off…. And then I photograph them! Matrilinear started with early images of those undershirts that belonged to my grandmother and transformed over a year as I began to work with more items of clothing. Initially, the images were straight-forward documentation but the more I worked with the material, the more they became about a familial legacy and folklore – as well as a cross-generational conversation with my ancestors – that required less documentation and more interaction. I started expressing stories through thread, which is a metaphor, not only for the physical and emotional work women do within kinship structures, but also for the time and space in which stories are often passed down – a once sacred space of building relationships through domestic work (childcare, cooking, sewing, washing dishes, folding laundry, etc.). I’m not implying that doing house work is fun but the gathering and the working and the attention to each other that can be shared over mundane tasks can be valuable.

HG: I like to think of the lightbox used to illuminate the items as a metaphor for the illumination of the overriding patriarchal society that we live in currently. Is that accurate?

EMC: This is such a thoughtful interpretation! Initially, using the lightbox was an aesthetic choice as it illuminated imperfections and also rendered the items ethereal – I was interested in expressing a simultaneous sense of life and loss... a particularly delicate pain. Pain is a well of knowledge and perspective, but we’ve been taught in western society to avoid and never discuss it for fear someone will see their own mortality in that reflection. But yes, I would say that you are accurate. This series, in shape and form, is designed to challenge the way that one defines knowledge, which has ultimately been shaped by patriarchy. How knowledge is defined and who is allowed to acquire it have always been an exercise of power by those in control, so the theories, wisdom, and experiences of “others” (women, people of color, religious minorities, the LGBTQ community, people of varying abilities, those with low income) are often unacknowledged as being of consequence or having value within the public realm. These images are meant to express alternative forms of knowledge development and collection.

HG: How do you choose the items to focus your attention on?

EMC: I have a large collection to choose from, and when I head into the studio, I often spend the first hour just sorting through and folding clothes. This gives me the opportunity to feel and smell them while also looking at patterns, tears, and stains – I work through the same pile or bag several times and always revisit it on different days. This is meditative and gives me a chance to daydream a little bit. Throughout that process, different items speak to me or spark my imagination and memory. My mentor, Susan kae Grant always said that if you listen, something will speak to you with urgency. She was talking about choosing which project to focus on, but I find that you can apply her wisdom to any problem and come out on the other side with a body of work. So, ultimately, I work with whichever item feels the most urgent at the time – Matrilinear #7 is a good example… I held those small shorts and remembered my own childhood, the scraped and bruised knees; the small flower pattern was a reminder of the constant expectation to be feminine and/or tame, a near impossible task for many young girls who desire an active or even aggressive physical experience in youth. Simultaneously, I thought of my oldest daughter, Margaret, who is 3-years-old: her bruised knees reveal so much about who she is, the risks she takes, and the small details of her daily life… as well as being a physical manifestation of how she is like her mother. In this instance, the thread became the broken or scraped skin on those once little knees. At times, the stories being expressed in these images are more about patterns of experience than a specific incident.

HG: "These interruptions also represent the deep influence of one’s familial past on personal identity and perceptions of the body." I find this sentence intriguing as it speaks to many things unstated. Please elaborate on the meanings within the sentence.

EMC: Through many conversations with my own family members and others who have shared their stories, I have learned that most often people know their ancestors through stories of birth, death, illness, and recovery. These stories of the body can reveal intimacies of one’s physical fears and expectations and also act as critical information when navigating personal health and identity. A personal example: my grandfather died just before Christmas when my father was eleven-years-old. His death shaped my father, then me, and now my children. I have memorized the narrative version that my father told me – it details his fear in seeing his father ill and on the way to the hospital, his family’s inability to discuss or even confirm the death, his conflicted experience of opening Christmas presents from his father, and of course, his reflections on how different his life would have been if his dad hadn’t died. I have also memorized the physical details of what happened, and every time I go to the doctor, I provide a medical history: my grandfather had stomach cancer but died on the operating table from a sulfa allergy. Familial knowledge can be an empowering force in the face of physical uncertainty, aging, and/or just trying to better understand one’s physical and emotional construct – we are DNA and lived experience, and both are passed down through generations. These stories are personal evolutions and can act as a foundation for understanding and self-acceptance.

HG: Thank you for sharing your work.

EMC: Thank you, Hamidah, for a wonderful conversation at Review Santa Fe and this opportunity to share my work on Strange Fire Collective!!

All images © Elizabeth M. Claffey