Q&A: Francis Almendárez

By Rafael Soldi | May 20, 2021

Francis Almendárez is an artist, filmmaker, and educator working at the intersections of history, (auto)ethnography, and cultural production. He uses these as tools to address memory and trauma, in an attempt to make sense of and reconstruct identity, specifically of Central American and Caribbean communities and their Diasporas. His work has been presented in group exhibitions at the Blaffer Art Museum, Houston, TX; San Antonio Museum of Art; El Museo del Barrio, New York, NY; and National Taiwan Museum of Fine Arts, Taichung, TW. He has had solo exhibitions and commissions at Aurora Picture Show, Houston, TX (2020); Galveston Arts Center, TX (2020); Artpace, San Antonio, TX (2019); The Reading Room, Dallas, TX (2019), Houston Center for Photography, TX (2018), and NX Project Space, London, UK (2016). Writing on his work has been featured in spot Magazine, D Magazine, Artforum, Hyperallergic, Glasstire, La Horchata Zine, and The Dallas Morning News among others. He is the recipient of an Artadia Award, the Carol Crow Memorial Fellowship, and artist grants from Y.ES Contemporary and the City of Houston. He has also been a participant of the Artpace International Artist-in-Residence program and the Institute of Contemporary Art Moscow Summer School. Born and raised in Los Angeles, CA, Almendárez is currently based in Houston, Texas where he is a Visiting Lecturer at the University of Houston School of Art and serves on the Board of DiverseWorks. He received his MFA in Fine Art (with Distinction) from Goldsmiths, University of London, and BFA in Sculpture/New Genres from Otis College of Art and Design.

Rafael Soldi: Hi Francis, thanks for chatting with us.

Francis Almendárez: Hi Rafael, thank you for the invitation to share and be in conversation.

RS: Tell me about how growing up in L.A. has influenced you and your work over time.

FA: Growing up in Los Angeles was really special and such a privilege but at the same time very stressful and emotional. I grew up down the street from the Coliseum and USC so I witnessed all kinds of events from the L.A. Riots to the Oscars. To this day, I am still seeing the impact my experience living there has had in my life and the influence it holds in my work. From live music to movies to murals and street food, art was everywhere even if at a young age I didn’t recognize it as such.

My parents always worked multiple jobs so starting in elementary I would walk home from school, and later on when I went to high school in the (San Fernando) valley, I would take the school bus or public transportation. There weren’t all these metro train lines during that time like there is today so these journeys would be hours long but that’s how I got to really know the city and my way around it. I bring this up because I haven’t gotten to know any other city the way that I knew L.A., where the physical landscape gave me a sense of orientation and direction. L.A. was the place where both my father and grandmother worked hard to buy a house, only to have it taken away as a result of the last global recession and financial crisis in 2007-08. So since being pushed out of Los Angeles, displacement, dislocation, migration, and disorientation have all become recurring themes in my work.

RS: I love this idea of looking to the past to recontextualize the future, especially as neighborhoods—which are often underestimated as repositories for identity, knowledge, and cultural history—are gentrified or white-washed.

FA: Yes, unfortunately we tend to overlook and undervalue the knowledge and lived experience of our families and our communities within our immediate proximity, and for those of us with families and communities scattered in other locations, in those places too. In the US, our understanding of knowledge, how it is produced and transmitted, has been conditioned by a neoliberal system of values and remains very Eurocentric and white supremacist. The “traditional” ways knowledge is manifested and preserved (such as books, newspapers, and artifacts in libraries, universities, and museums) privileges certain narratives, experiences, and modes of learning over others. That’s not to say that traditional modes of teaching are bad or wrong, but rather that they are a small sample of a multiplicity of ways for teaching and learning.

When it comes to our communities of color, we’ve been improvising, learning by doing, and co-existing with the land and all living forms around us for generations and centuries. We have been practicing interconnectedness and solidarity as a way to resist, preserve, and/or survive the genocide, slavery, Christianization, and/or eradication of histories and cultures imposed through colonialism. If you look and listen closely within your family and your communities, you will find traces of these struggles and histories.

I think families and communities of color that find themselves dispossessed are in a much tougher and more vulnerable situation that becomes more specifically focused on survival alone. It’s within these kinds of situations that other modes of knowledge come into play, including improvisation in which they draw directly from past lived experiences and knowledge transmitted to them from previous generations. I’m referring to people in the process of im/migration or living nomadically but also referring to my own personal and familial experience of being pushed out of Los Angeles.

RS: Can you talk a little more about the importance of vulnerability and using yourself as an entry point? How do you balance using your personal experience to speak and relate to a broader audience?

FA: I use myself and my experience as a point of departure because it’s my story and it’s the one I’m most familiar with. My whole reason for making art is to connect with people and placing myself in a vulnerable position allows me to earn the trust of my audience and my collaborators so that together we could begin to dialogue and find ways to reconcile and/or ameliorate. Working in such a way definitely takes its toll which is why I now give myself more time in between projects so that I could process it all.

After my last two films, I’m leaning more towards working on larger projects that take a lot of research, longer periods of time, and as a result force me to slow down. This process allows for the time and space needed to balance such personal and vulnerable work. However, I’ve noticed that after completing these large projects, I have been left feeling drained and exposed. So it is absolutely necessary to find this balance and honestly I’m still learning as I go so I can’t say that I’ve got it down perfectly.

RS: You started out as a musician, correct? Tell me more about that! How does this show up in your practice?

FA: Yes, that is correct. Not many people know this about me but I started my journey in the arts as a musician. As kids, my grandma would always take us to see the Rose Parade in Pasadena, CA and I remember seeing the marching bands and wanting to play the trombone. I didn’t know the name for it so when I began taking music classes in elementary school I was just assigned the violin. At the concert held at the end of the school-year, I saw other kids playing the trombone and I remember telling the band director that I wanted to learn how to play it. The next year I switched and I would go on and continue playing all through middle and high school. Initially, the trombone was larger than me, and my arm couldn’t physically extend to reach certain notes but eventually I grew into it. I really loved being part of a larger group where we each had our role to play, if anyone was missing, the whole thing would fall apart or be incomplete. Now looking back, I see these performances as my first collaborations.

All these years playing music were very formative for me in a number of ways. I was exposed to music from many different cultures and learned about the histories and contexts they were created in. I became fascinated by all this; particularly how music could be used to tell stories and had the power to convey emotion. As I grew older, I became more and more intrigued by the different sounds and textures different instruments could create, especially non-traditional instruments being brought into concert band and orchestral settings, or traditional instruments being played in non-traditional ways. Looking back today, I realize how lucky I was to have a world-renowned oboist, Dr. Richard Kravchak, as my high school band director.

Without any of these experiences, I probably wouldn’t be making art today. Or maybe I would, but it’d be very different. I don’t think I’d be working with sound, performance, nor collaboration. I’d say the impact of my musical background is most visible in my video/film work and my decision to work in time-based media which allows for the merging of image, music/sound, and storytelling. It is through these artistic modes that I’m able to dig into my interest in the body, performativity, and the processing of time, duration, and rhythm in relation to labor, memory, and trauma.

RS: Let’s talk a little more about your performance work—Navigating The Archives Within, for example. Can you talk a little more about that piece? What was it like bringing that to life in the middle of a pandemic, did it change?

FA: You know, I envisioned this work being one thing and it ended up being something much larger than I could ever imagine. I love how and when that happens; it confirms the trust I place on myself, my collaborators, and our processes. While the pandemic postponed the production of the work it also forced us to improvise on how to move forward which coincidentally is one of the themes of the work.

Navigating the Archives Within is an experimental film and performance that proposes the body as a living archive and questions how histories, cultural traditions, and personal experiences are kept and transmitted. It merges original and archival imagery with live readings and improvised music to explore distinctions between "official" narratives, marginalized histories, and subjective memories while blending and remixing them. The performance was filmed live at Aurora Picture Show (Houston, TX) and premiered online in early December of 2020. The 36-minute film essentially captures an autoethnographic journey through Latinx misrepresentation, erasure, subordination, and subversion.

To me it was really important to carve out space for this type of experimental work, and for artists of color who work in these modes that are immaterial, time-based, somatic, performative, collaborative, and communal. These modes of production are so often overlooked and excluded, and it’s artists of color primarily who are really pushing artistic boundaries and making radical work.

For me, this work is just as much about its form, as it is about its content. It is about occupying a space of in-betweenness, of multiplicity and simultaneity, and of invisibility. And how do you negotiate these different identities and positions? I really wanted to talk about the grave absence of narratives, histories, art, and scholarship that touch on the experiences of Caribbean and more specifically Central American diasporic communities in the US. However, in order to do so I needed to go back further and look at the history of visual representation in Hollywood cinema and the role of the camera as a violent weapon of racial formation. In the end, I didn’t get to directly address the history of the Central American diaspora but that absence or invisibility still speaks volumes and gives me a destination to work toward.

RS: A project like that requires a lot of collaboration, I imagine. Do you collaborate often in your work?

FA: I would say that all of my work has been collaborative, it’s just never been framed that way. I’ve been much more conscious of this in the past couple of years as my work has been enabled to become larger and more ambitious. While I was a student, I was really turned off and isolated by the competitiveness I witnessed. However, through those experiences I was able to meet other like-minded artists and together we helped each other bring our projects to life. I really enjoyed and learned a lot from doing this because we each brought with us a different set of skills and expertise.

When I moved to Houston I began working more directly with my brother who is a musician and composer. Houston has an extraordinary experimental music and sound scene and between the two of us we’ve been able to meet and collaborate with other artists and musicians. Gradually over time we also began involving our immediate family. It was a way for them to gain an understanding of what we do, and for us a way to defer questions around making money to survive. In sharing the process with them, we noticed it gave them a sense of pride, worth, belonging, and authorship that I really enjoyed witnessing. It really broadened my views of art making to where the processes and relationships are just as important, if not more, than the final product or outcome.

RS: Let’s go back to archives, and this concept of the body as archive, which I really relate to. How do you personally relate to the archive in general, and how does it show up in your work?

FA: As immigrants from Central America, my family never imagined my brother and I doing this kind of work and being able to live off of it. (I mean we still can’t but that’s a different conversation for another time.) The only reason this is at all possible is because of the sacrifices our parents, grandparents, and countless others have made. That being said, I see my work as a way to honor them and pass on this history for posterity.

I’m very much interested in this history and these forms of knowledge which manifest in many different ways. I’m particularly interested in immaterial forms of knowledge, specifically music and dance and how they have been able to preserve and transmit ancestral knowledge, histories, and cultural traditions over generations.

As we all know, history has been and continues to be written by the victors or those who hold power. The history of the Americas that we could easily access is through the lens of European colonizers who eradicated the histories and material cultures of Indigenous and African peoples. This is by design and as a consequence, look at the state of necro-politics we are in today and who endure the most. Of course, this is an oversimplification, but we know where this history of violence and extraction stems from.

Nevertheless, music and dance, in addition to being ways for us to express ourselves, have historically been employed as forms of resistance, preservation, and communication during times of oppression. They have been the way in which knowledge has been produced and transmitted through the body thus making the body a vessel, an instrument, a living archive that essentially fills the gap of a lacking material history.

As much as they claim to be progressive, the art world and all its institutions are no different in their privileging of certain histories and cultures at the exclusion and erasure of many others. During these times of quarantine when conversations around inclusivity, diversity, equity, and access have resurfaced, it has become even more obvious through the pushback we see everyday on the part of these institutions, specifically their leaders who refuse to change or step down. They have no interest in ceding power or control and therefore they won’t. So in this present moment this ongoing work and these conversations around archives couldn’t be more timely.

If we look at museums (and collectors) and what they actually collect, we see at play their systems of values, their tastes, and their obsession with ownership, hoarding, and exoticzing which are all reflective of the conquest and empire this country and “the West” is built upon. This is what draws me to the familiar; the music and dance of the Caribbean, that both have historically been produced and transmitted immaterially through the body as a direct response to oppression and erasure. No matter how they are appropriated, repackaged, or expanded upon, at their roots remain the African and/or Indigenous rhythms and influences they derive from that cannot be erased or concealed. If you look around and listen, you will see, you will hear, and you will feel this presence. It is here to stay, it’s not going away. To me that speaks volumes and is much more profound than any physical object or archive.

RS: I’d love to touch a little more on your writing practice, which I know is important to you. How does it fit into your work in terms of—you’re already working with a variety of mediums and tools. Is writing just another medium? Or is it some kind of foundational element on which other techniques/approaches/mediums can stack on?

FA: Yes, writing has become very important for me over the years but I don’t think of myself as a writer. I say that because I’m not formally trained as one and I don’t use writing as my primary medium. I do however write prose from time to time but I only recently began doing that a few years ago without even knowing what it was. In a society that depends on writing in order to make things “official,” I do recognize the necessity, importance, and value of it. This reminds me of Grada Kilomba’s video While I Write in which she eloquently states, “I write because I become the author and authority on my own history.” This has always resonated with me and I often come back to this work as a reminder and a source of motivation.

I would say that I use writing in a way that most artists use drawing. Although I was formally trained to draw, I hardly ever do it. I just put things together and take them apart and repeat until I get whatever it is I’m looking for. The bits of fragmented writing help throughout the process to ask questions, to rant, form opinions, put feelings into words, and make sense of what I’m thinking, what I’m doing, and how they may or may not come into alignment with the work. I feel like sometimes my brain needs to catch up to my body or vice versa. It takes me a long time to make work so writing becomes a way to keep tabs on it all. Sometimes the bits of fragmented writing actually get merged or stacked onto other mediums and become a part of a work but most of the time they remain as fragmented bits in my accumulation of notes.

RS: Storytelling is a strategy that often appears in your work as well. As a fellow Latinx person, I know that storytelling is a powerful vernacular tool in our culture. Be it oral histories, family albums, or myths, superstitions, and fables—these are all tools that have been used by generations to fight against institutionalized, colonial archives that seek to describe, define, and erase us. Does this resonate with you? Do you have a similar or different relationship to narrative and storytelling as it relates to your practice?

FA: Absolutely, my work has always been about narrative and storytelling, and I’ve always faced a lot of pushback for it, especially as a student. In fact, there was even a period of time where I didn’t like calling myself an artist and instead considered myself more of a storyteller. Now I think of myself as all of the above but it took me a long time, and a lot of learning and unlearning for me to finally reach that point.

So to answer, yes. Storytelling and narratives do resonate with me; however, I find it problematic when narratives and certain forms of storytelling are co-opted and exploited which is why in my own work I like to question:

Who is it for?

Who does it serve?

Should I really be the one telling this story?

Is this really the best way to tell it?

I also worry about the paradox found in narratives and storytelling, especially when they are co-opted and exploited by others. It is a problem that we all face when operating within institutional structures including the art world. The making of art objects or material culture, despite artists’ good intentions, more often than not, fall into this trap of needing to be bought and collected thereby perpetuating and fulfilling these obsessions with ownership, hoarding, and exoticizing. Even with Latinx art which is trying to make a claim for itself, you see that the few institutions that support it and the key influential figures that champion it, both directly and indirectly privilege certain artists, narratives, and types of artworks based on nationality, city they live in, school attended, and/or other similar (if not the same) systems of value that mainstream museums, galleries, and other institutions defer to and so adamantly uphold. In such a conundrum, I question if this is really the best way to go about storytelling and truly being inclusive, diverse, equitable, and accessible? If this small minority of gatekeepers are merely replicating the same model, biases, and nepotism to only include their circles, experiences, tastes, and areas of interest and expertise, then how is it any different from the failing model that already exists? These systems of value are designed to exclude, suppress, and depreciate the labor, production, contributions, and value of BIPOC communities so it is necessary to dismantle them if we truly want meaningful and lasting change.

RS: Thank you so much, Francis. Are there any upcoming projects that you’d like to share with us?

FA: You know, I’m currently on hold and just trying to process the last year and figure out how to best move forward. I’ve been writing a lot as a way to develop my next project using Navigating the Archives Within as a point of departure. I’m definitely looking forward to traveling, collaborating, and experimenting more as a way to continue expanding my work and the way it is accessed and circulated. A lot to think about...

Rafael, thank you so much for this invitation and for your really thoughtful questions. It’s not everyday I get the opportunity to talk about these challenges which I think are very important to discuss so I truly appreciate your time and interest.

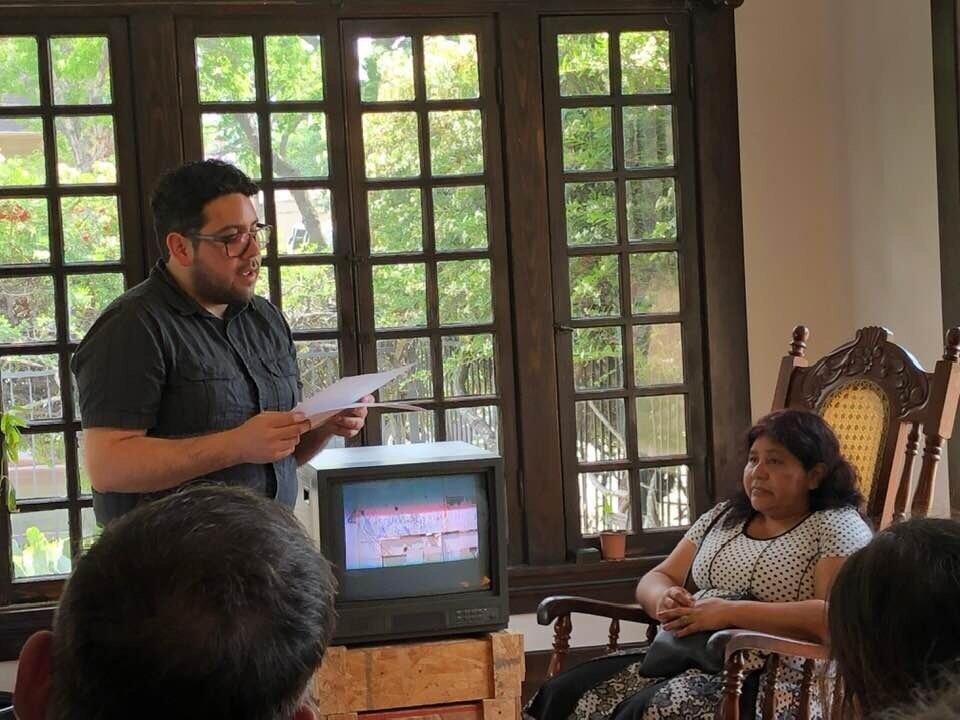

(be)coming home, 2019, 3:48 TRT, Single-channel video installation: CRT monitor, media player, wooden crates, rocking chair, stereo sound, installation dimensions variable. Sound Editing by Anthony Almendárez.

Teaser of Navigating the Archives Within, 2020

Production stills from Navigating the Archives Within, 2020. Photos by Laura De León

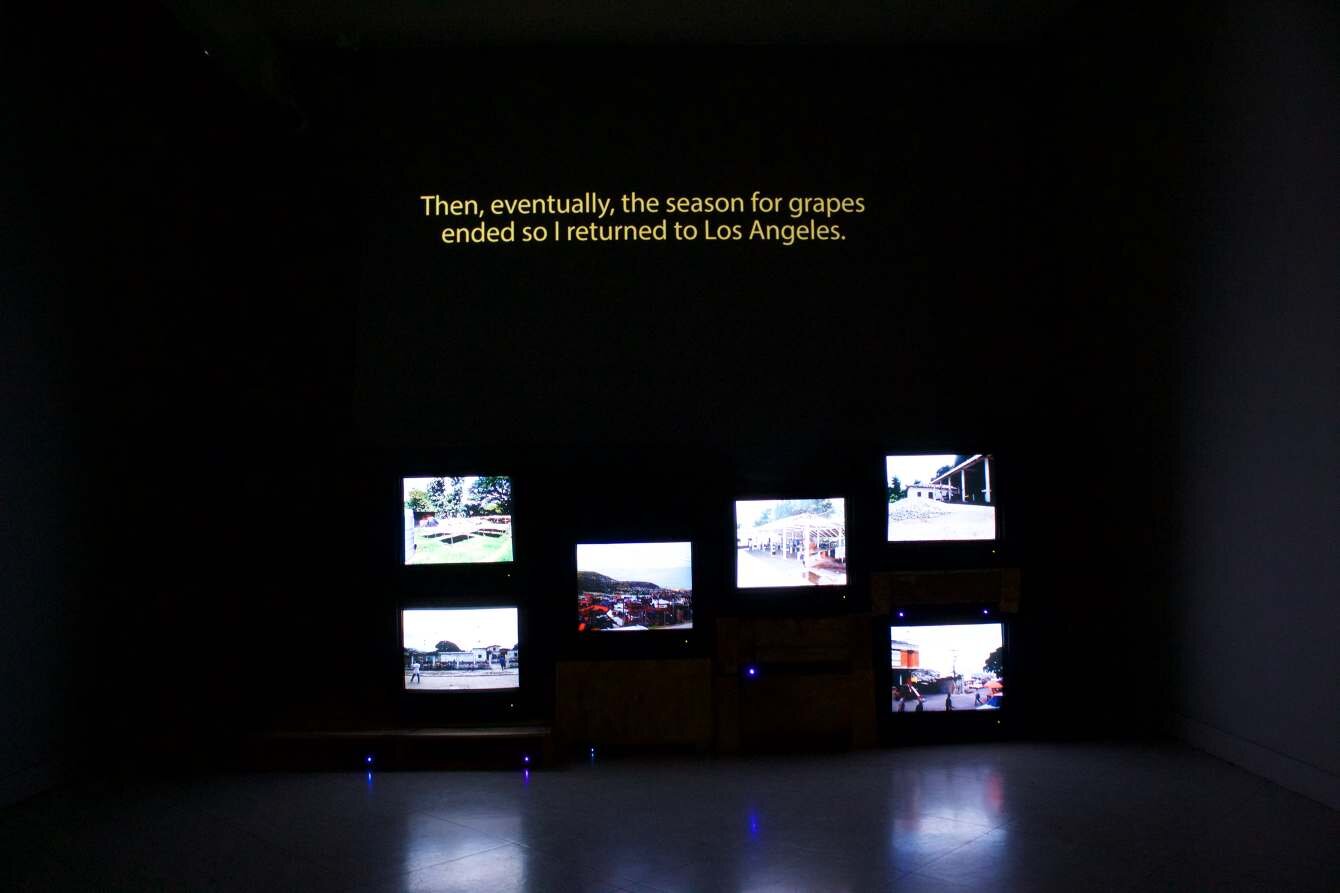

Installation view of Voices of Our Mothers: Transcending Time and Distance

Installation views of rhythm and (p)leisure at Artpace, San Antonio, TX in 2019. Photo by Seale Photography Studios

Composite View of rhythm and (p)leisure

Documentation of Performance and Reading at the exhibition The Potential Wanderer at The Reading Room, Dallas, TX, USA. January 19, 2019

The Potential Wanderer, Installation view at The Reading Room, Dallas, TX in 2019. Photos by Kevin Todora

Composite View of The Potential Wanderer