Q&A: Keliy anderson-staley

By Jess T. Dugan | June 16, 2016

Keliy Anderson-Staley was raised off the grid in Maine, studied photography in New York City and currently lives and teaches photography at the University of Houston in Texas. She holds a BA from Hampshire College in Massachusetts and an MFA in photography from Hunter College in New York. Anderson-Staley's images are in the permanent collections of the Library of Congress, Cedar Rapids Museum of Art, Portland Museum of Art (Maine), and Museum of Fine Arts-Houston. She was the recipient of a New York Foundation for the Arts Fellowship, a Puffin Grant, a fellowship from the Howard Foundation, the Carol Crow Fellowship from the Houston Center for Photography and the Clarence John Laughlin Award from the New Orleans Photo Alliance. Her work has been shown at the National Portrait Gallery of the Smithsonian, Portland Museum of Art, Akron Art Museum, Bronx Museum of Art, Southeast Museum of Photography and the California Museum of Photography, as well as at a number of galleries around the country.

Anderson-Staley has been making wet plate collodion tintypes and ambrotypes for eleven years. Her series of tintype portraits was published in 2014 under the title On A Wet Bough by Waltz Books. She is represented by Catherine Edelman Gallery in Chicago, IL.

Jess T. Dugan: Let’s start with a fundamental question. How did you discover the process of working with wet plate collodion tintypes and ambrotypes, and at what point in your career did you make the switch to working primarily in this medium?

Keliy Anderson-Staley: As interested as I am in process, I’ve always thought of myself foremost as a portraitist. I love people, love getting to know them, love making images of them that they are proud of or that really impact how they see themselves.

I made my first collodion plate in 2004. I was working with Joni Sternbach and her husband Eric Taubman around the time they were establishing the Center for Alternative Photography in New York (now known as Penumbra). I was completing my MFA at Hunter College and working mostly in color film for my thesis. I’ve always been interested in darkroom processes, and collodion was an immediate fit for me. It’s hard to say why exactly, except that I liked the connection to history, the materiality of the end product, and the physical engagement with the materials.

Davon

I ended up teaching a number of tintype workshops at the Center for Alternative Photography and started making portraits at my studio in Queens. In 2005 I started exhibiting my work in small venues around New York City and eventually around the country. I’m not sure I would say that I’ve switched over to this medium at the expense of others. For example, I’ll be shooting new medium format color film in Maine later this summer.

JTD: Speaking of Maine, I first became aware of your work when you were making your series Off the Grid, which focused on communities living off the grid there. This project is embedded with a sense of shared humanity and community, which I also feel in your tintype portraits. Would you say a search for a shared humanity is an integral part of your work? What would you identify as the underlying idea that compels you to make portraits?

KAS: It is important to me as a photographer that people aren’t exploited or exposed in ways they wouldn’t be comfortable with. I think what surprises some people about my Off the Grid series is that the people in it are so ordinary and their lives so mundane. Some of them are what might be considered real fringe characters, but I am not interested in portraying them as such. Because of Off the Grid, I am contacted all the time by producers for reality shows looking to find a cast of characters for various survival type programs. Honestly, I never thought that’s what this project was about. I wanted to explore how people make their homes, how they live, how their ideology shapes their lifestyle, but also how that lifestyle fits into broader social patterns.

Tom Shaving, Guilford, Maine, from Off the Grid

I grew up off the grid in Maine, and many of the people I photographed are family friends or people I found through friends of friends. In a sense I was always looking to tell my own story, and to, maybe, normalize something that most people would consider extreme.

A portrait can only ever show someone as they exist in a single moment, and when we see portraits, we can only see what’s given to us in the frame. To be really successful, I think a portrait needs to leave us feeling like we maybe now know this person, or that maybe if we studied it long enough we could. One thing I’ve always liked about collodion is that the long exposures mean that you capture the person over an extended period of time. There seems to be an intensity that gathers in their gaze. I like that when the portraits are installed, they have a real presence, as if the person is in the room looking back at you, demanding to be seen. I don’t want to speak for anyone when I make a portrait of them, and I hope to leave space for them, through their expression and posture and gaze, to play a significant role in how they are perceived.

JTD: Tell me about what you’ve been up to in Cleveland. It has been wonderful to watch you make work there recently. How did this project come together, and who was involved in making it happen?

KAS: I have been working on a major public commission for the city of Cleveland. There are artists and muralists from all over the country installing artworks along the red line of the RTA Rapid Transit. I am one of three photographers completing a project. LAND Studio, with funding from the Cleveland Foundation, Greater Cleveland Regional Transit Authority (RTA) and the Northeast Ohio Areawide Coordinating Agency. All of us are responding to themes inspired by the Anisfield-Wolf Book Awards that "celebrate the rich diversity of cultures and the artists, writers and people that open and challenge our minds." The photography side of the initiative was curated by Fred Bidwell of the Transformer Station and Bidwell Foundation.

I was commissioned to make portraits of Clevelanders, fifty of which will be enlarged to 40 x 50 inches and installed in the tunnel leaving the airport. All of these works will be up before the Republican National Convention and will remain in place for at least five years. Among my subjects were Cleveland area artists, writers and other people in creative fields. The portraits will be one of the first thing visitors to the city using transit will see. Settled by waves of migration including the Great Migration, Cleveland is a very diverse city, more than 50% African-American. This project will showcase this diversity while the whole world turns its attention to politics in Cleveland.

The portraits were made at a number of venues around Cleveland, including the Transformer Station, Cleveland Institute of Art and the national headquarters of the Society for Photographic Education (SPE). SPE invited me to Cleveland to install a solo exhibition of my [Hyphen] Americans project (which will be on view until the end of July) and to give a workshop and portrait demonstration. James Wyman, the director of SPE, and SPE were instrumental in bringing me to Cleveland. Making the images and the time I spent getting to know people from across the city is what is most rewarding to me. I've been posting images from the portrait series on my Instagram feed.

Jennifer

JTD: I have often seen you put out a call for subjects in a particular city or place, such as at an art fair or a non-profit organization. Are you drawn to certain kinds of subjects, or is it more a matter of responding to whoever you find in front of your lens?

KAS: I’ll photograph anyone willing to sit for a portrait. At the venues where I set up, the institution will usually put a call out, but there is also word-of-mouth buzz, too. Some of the individuals included in my 50 portraits of Clevelanders just happened to be walking by. When someone sits for a portrait, my goal is to get the best portrait of them I can. I’m often surprised by which of the portraits I end up falling in love with. I really can’t predict it when I’m first meeting someone.

JTD: I love that, in almost all cases, your subjects are looking directly out of the frame at the viewer. How does this direct eye contact function for you? What do you hope it inspires in the viewer?

KAS: I was talking earlier about the intensity of the gaze of the sitter, and that is really important to me. I want the viewer to feel like they are really engaging with the subject. In the image, they really do seem to be staring, but it is a photograph, so we can stare back without feeling uncomfortable, and we can really look at them. Because they are so assertive in their gaze and posture, our judgment is curtailed. We can make assumptions about who they are and where they come from, but as we stare we realize that we may be wrong—we cannot be certain about class or ethnicity or age or race or gender. So many of the categories that our culture treats as stable and determinative suddenly seem fluid, in flux.

JTD: When you are photographing, what is the most exciting moment? Is there a particular experience that you find especially nervewracking or exhilarating?

With collodion, the portrait develops instantly, and I love to share that experience with the people who sit for me. Watching the plate turn from a positive to a negative while the person who just sat for a portrait gasps in astonishment or records the process on their phone is always really exciting.

I often set-up in high pressure situations. I’ll be at a venue for a day or two, and people will have signed up for portraits with only 15 or 20 minutes between each appointment. I only have one chance to get a portrait of each sitter. I sometimes fall behind and crowds can start to gather. When everything is going perfectly it can be exhilarating and the adrenaline kicks in and it’s like a public performance. But the chemistry is fickle and my equipment gets a lot of use, so things can go wrong and when they do, the problems can start to compound. That can be a little stressful.

JTD: Your beautiful monograph, On a Wet Bough, was published in 2014. It must have been difficult to put together an edit for a book out of your vast archive of images. What was this process like?

KAS: It was difficult. When I did the edit in 2013, I already had thousands of portraits, and I was still making them throughout the book-making process. The edit was set early on, and it includes portraits going all the way back to 2004, but I couldn’t think of the new portraits I was making as contenders. Since then I’ve made hundreds more. I worked closely with Mary Goodwin, publisher and editor at Waltz Books, on the edit. I was living in Arkansas at the time and she and I spent a whole weekend picking and choosing from hundreds of tintype plates I had tacked in plastic sleeves to the wall. Images were chosen because they were strong or were of interesting people or because they worked well at a particular point in the book. Just as when I put together an edit for a show, sequence is crucial—what faces look good together? What individuals seem to be in some kind of conversation with each other? What echoes can be found between faces, even among seemingly very different types of people? Fortunately, Mary and I agreed on nearly every choice. Sequencing and editing can be so subjective, even when there is a system and a logic to it. I was lucky that our intuition often matched and that she was so interested in making such a beautiful book that could be true to the spirit of the project.

JTD: More recently, you have begun to make abstract collodion tintypes. What inspired you to work in this form? What is your process for making these images?

KAS: My project, Found Unfound, includes a number of new abstract tintypes. The project has a personal origin: the first time I made contact with my biological father, Bill, was 2013, the same year I became a mother. The following summer, I went to California to meet him. Until my mother told me when I was twelve, I did not know that my father, Tom, who had been raising us in an off-grid cabin in Maine, was not my “real” father. More shocking was that he had always known, but chose to raise me as his daughter. My mother gave me a single blurry photograph of my biological father—the only one she had—but I lost it a few years later. The image had told me very little, but I mourned its loss severely, exaggerating in my mind all the information and history it must carry.

Now that I have connected with Bill, I have been working in and around the space of this absence, making a new photographic history and reexamining the photographic record I do have. Over the past year, I’ve photographed both of my fathers several times, traveling with all of my wet-plate collodion photographic chemistry and equipment to them in Maine and California.

Installed as a grid, the portraits vary in their clarity and what they reveal; none can serve as a definitive portrait of either man. Some of the images are dark and obscure, others overexposed, still others are almost lost in the chemical idiosyncrasies of the process. The men also look uncannily similar. The portraits at once evoke feelings of ambivalence, admiration, confusion and empathy. Recently, I further complicated the story, by photographing my ex-step-father and including his portrait in a series of triptychs.

Installation View

As a single installed piece, the portraits suggest the impossibility of truly knowing anyone. Formal portraits such as these serve as the backbone of our family histories, but this set does not resolve questions of identity and the dual title of the piece (“Bill, Tom: Father, Dad”), points to the unsettled nature of my relationship with both men. The portraits, even as they multiply, only leave me wanting.

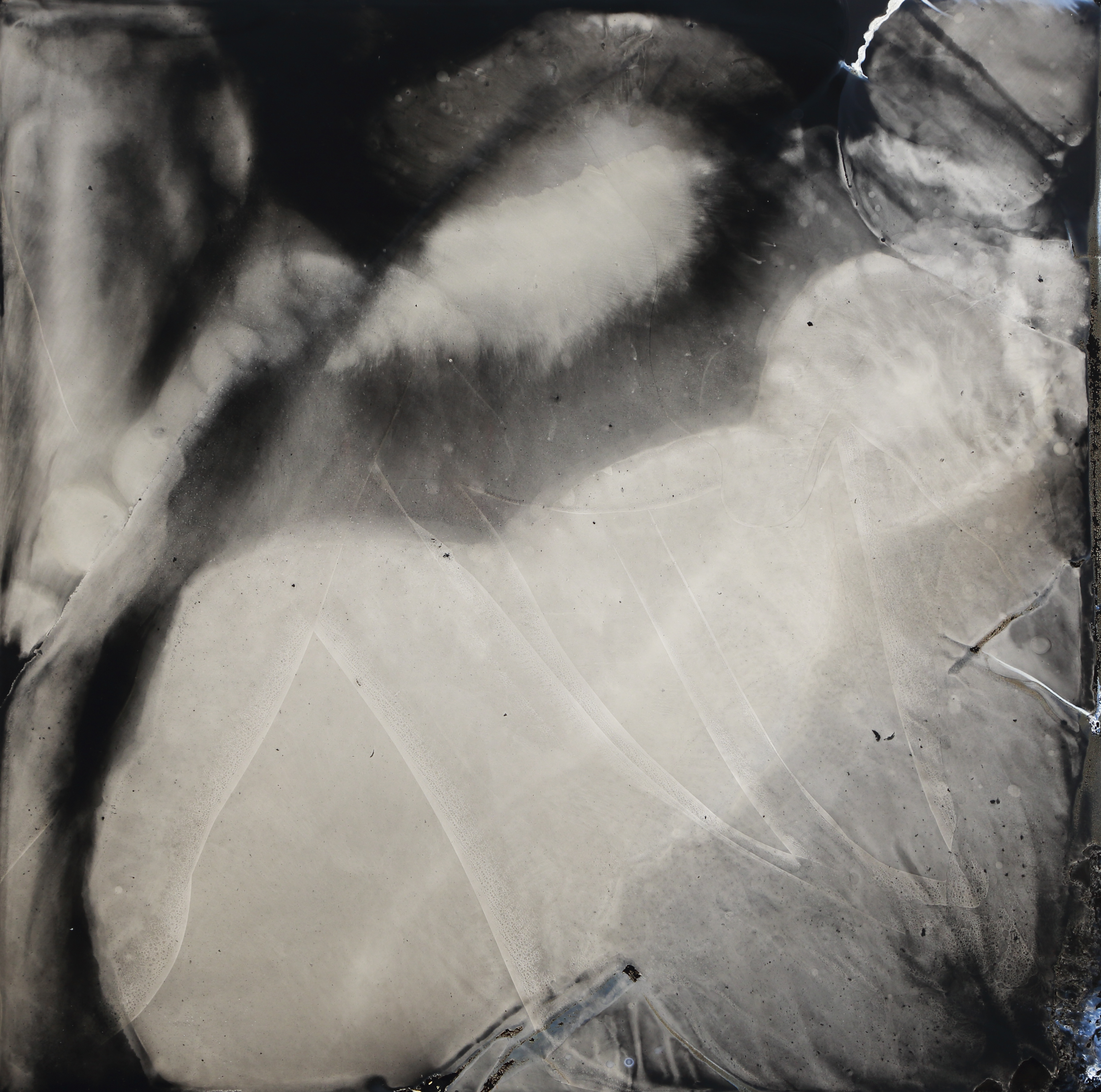

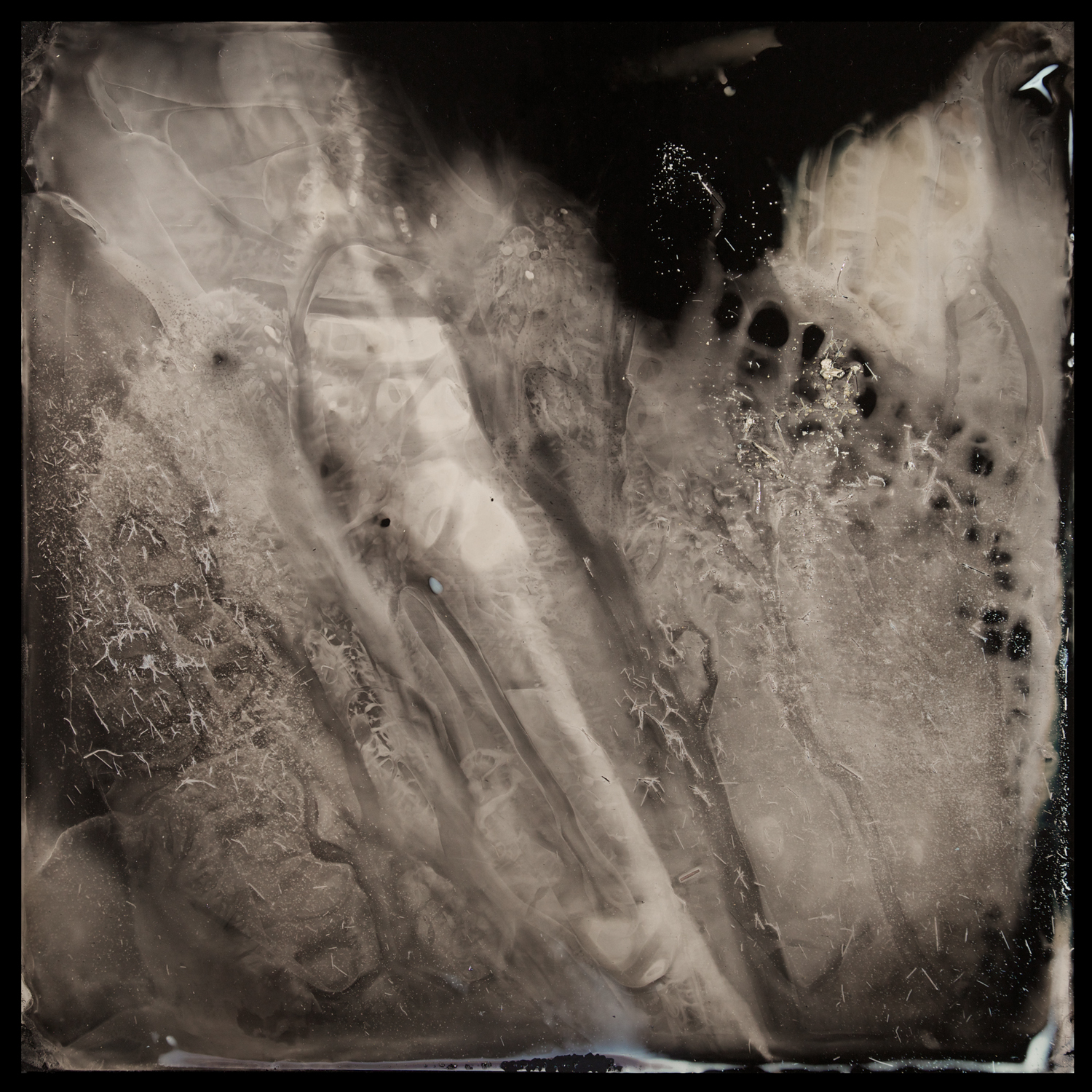

The lost photograph of Bill was in my mind as I began making the abstract works, and so were the photographs that might have existed from a parallel hypothetical life with him. The abstractions are crucial to the story of my discovery of Bill, a story that is filled with holes, secrets, unknowns and the unreliable versions of events I have gotten over the years from the figures involved. The abstract pieces are each titled with the date and time they were made—a kind of journal of psychological states.

Album, 1:15 AM, October 17, 2015, 24x24"

The photograms are made by controlling where and what kind of collodion is applied, how the plate is dipped in silver, in what patterns and concentrations developer is applied and how much fix is allowed to eat into the image. At every step of the chemical process, it is possible to affect the highlights, mid-tones and dark areas of the composition. Areas of light and negative space and the interaction of the various layers of chemistry produce dynamic contrasts in the image. There is an interplay between the deliberate crafting of the images and the accidents and randomness of the process. Visually, these abstract pieces echo the chemical aberrations of the portraits.

Album 10:44 PM, Nov 27, 2015, 24x24"

The plates suggest a latent image. As such these pieces are also meditations on birth and becoming. Motherhood is a central theme in this story of fathers, and through these images I began to address my complex emotional responses to being a mother of two young children and becoming a daughter again to a stranger.

JTD: Where do you find inspiration?

KAS: In art, in literature, in my family and my children. I try to see as much art as I can. I travel a lot to make my work, and I would never think of going to a new city without spending some time in their museums.

JTD: What’s next for you as an artist? Do you have any projects or exhibitions on the horizon?

KAS: I will be putting steady work into my Found Unfound series, developing new abstract work for that. My plan is for that project to be my next book, and a lot of my energy will be spent on that.

All images © Keliy Anderson-Staley