Q&A: Kris Sanford

By Hamidah Glasgow | October 26, 2016

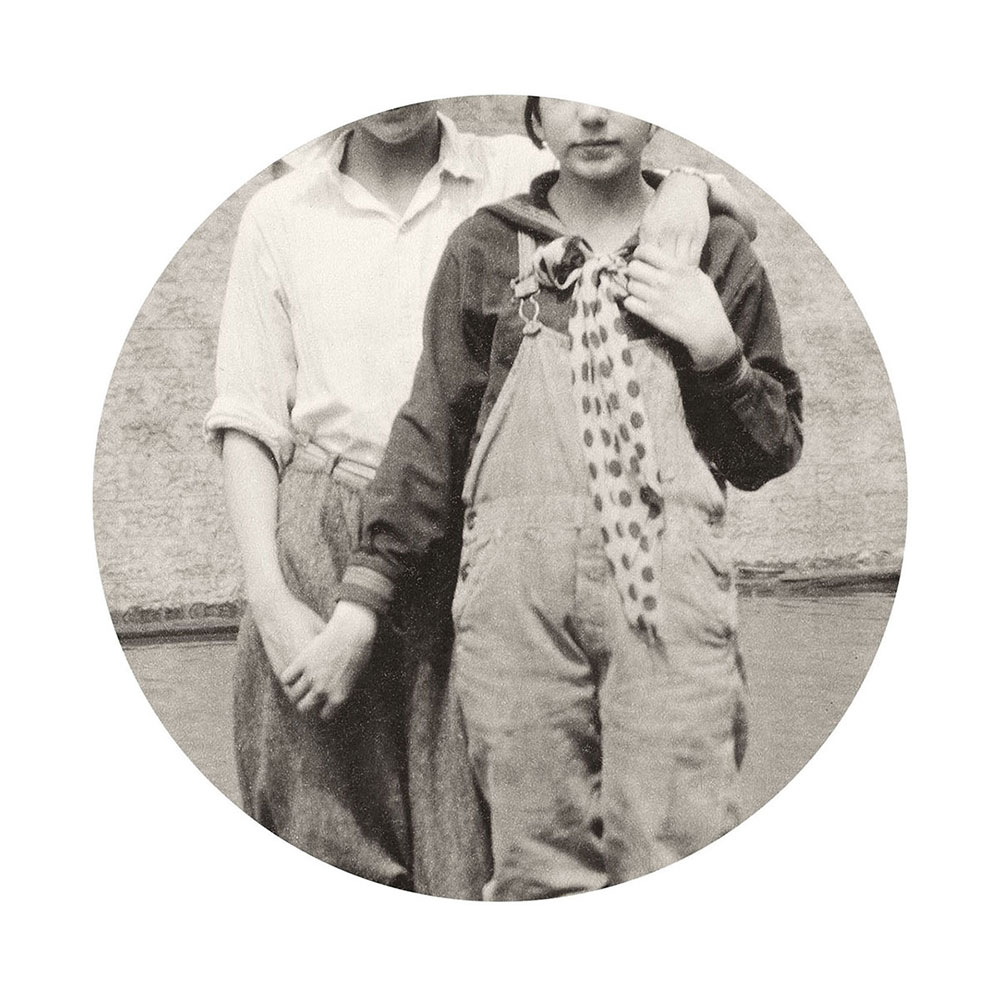

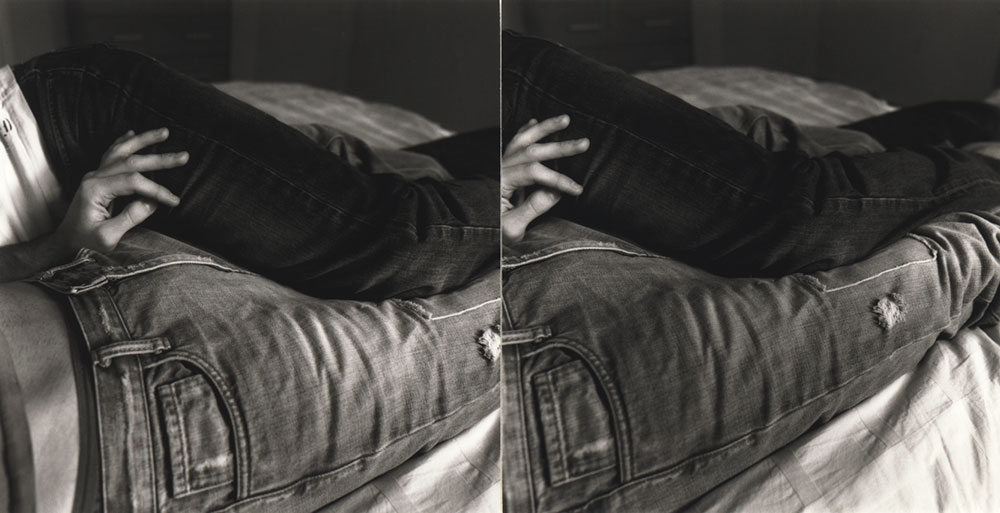

Photographer Kris Sanford's art work projects queer relationships onto vernacular photographs as a means to generate images that show a world in which she can see herself. It’s a powerful series that in its simplicity, through gesture, touch, and the view through a lens, allows the viewer to ponder the possibilities of these subtle relationships.

Her art explores intimate relationships, specifically queer desire, through the use of appropriated images and text.

Kris Sanford has exhibited her work nationally and internationally, including group exhibitions in Boston, Chicago, Denver, Detroit, Houston, London, Miami, and New York. In 2010 she was awarded a Contemporary Forum Artist Grant from the Phoenix Art Museum and her work was selected by the Phoenix Public Art Program for the 2011 installment of the 7th Avenue Streetscape Panels. She is represented by Catherine Couturier Gallery in Houston, Texas and Tilt Gallery in Scottsdale, Arizona.

HG: Congratulations on making Photo Lucida’s Top 50. I’m thrilled to say I was among your admirers on the review panel. The work that was selected for this honor is, Through the Lens of Desire, where you re-imagine vintage photos and the intimacy contained therein. How did you start this project? Even more specifically, did this project stem from the body of work Stereographs?

KS: Thank you so much for the kind words, Hamidah. The series is somewhat of a continuation or evolution of an earlier project, titled Cropped. I’ve been using vintage snapshots as source material (in a variety of projects) for about 10 years. The earliest source of inspiration for my work with old photographs was a box of snapshots that I inherited from my grandmother (on my mother’s side). A number of these snapshots depicted playful parties she hosted for her friends from work, where they sometimes dressed up. There is one of two women dressed as flappers dancing with each other. Another depicts my grandma dressed as a bride next to another woman dressed as a sailor, engaged in what appears to be a mock wedding. To my modern eyes, as an out lesbian, the pictures looked so queer. So I started experimenting with that collection in graduate school, changing the scale by enlarging them or adding text or cropping them. I quickly outgrew the family collection and began searching for photographs that were ripe for this kind of reinterpretation. The tight crop is very consistent with the stereographs, which were made between Cropped and Through the Lens of Desire. I tend to see that way often, whether I’m looking through the viewfinder of a camera or looking at snapshots of the past.

HG: Is the tight crop about intimacy? About the viewer having to lean in to your images, and in that gesture asking them to be intimate with the image?

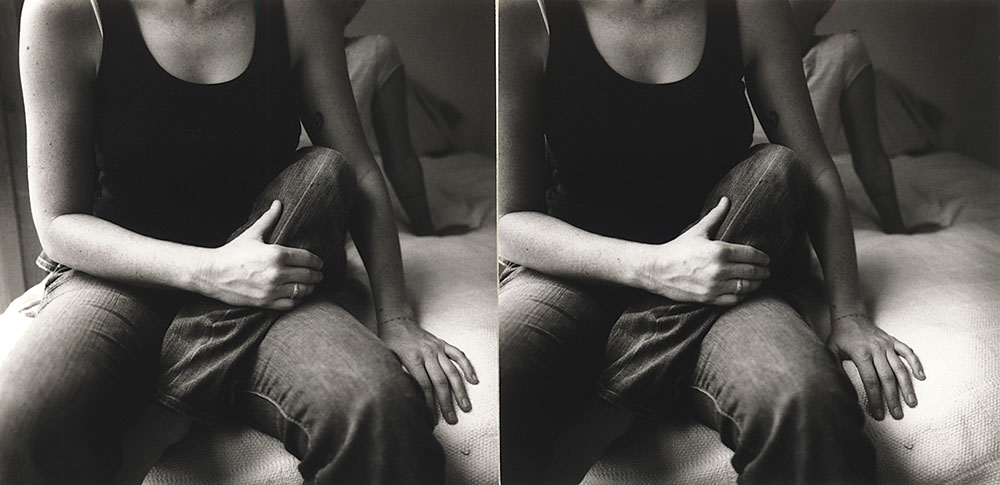

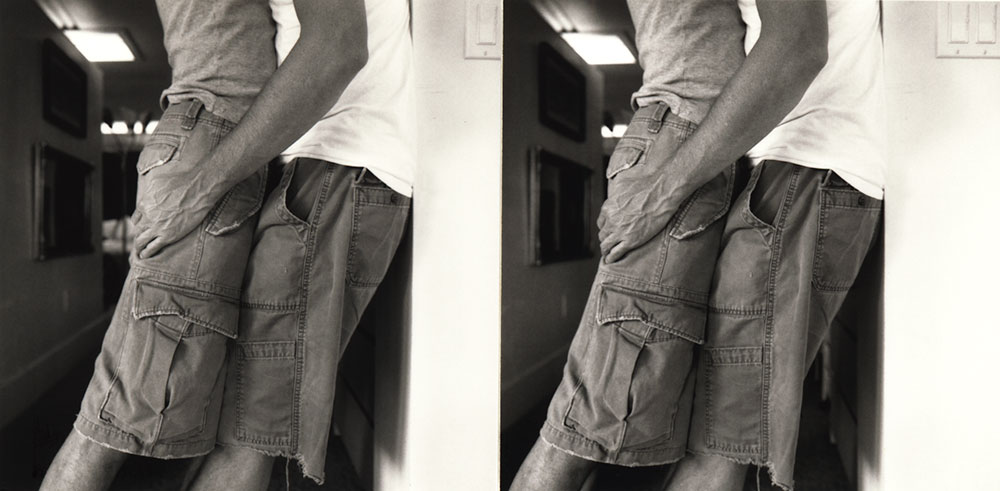

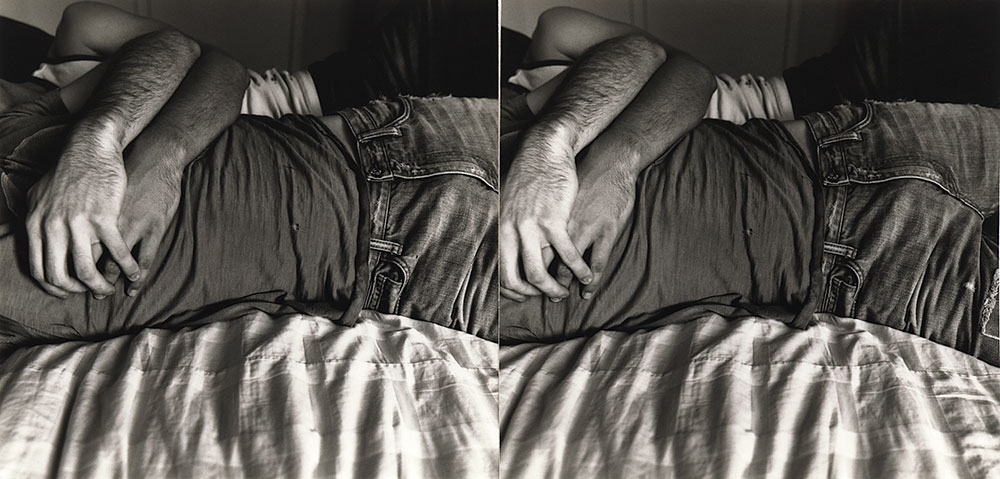

KS: I don't know that I've thought about the crop itself in quite that way. But that is a lovely way to look at it. I do think about intimacy when it comes to print size and often print rather small. Viewing a 3x5" snapshot is an intimate experience, so I often make prints that one has to get close to. The crop is certainly meant to highlight the gestures contained in the photograph and to introduce some ambiguity to the scene. The image becomes more specific but then also opens up to more possible interpretations. The idea behind the stereographs was definitely to create an intimate viewing experience.

HG: I’m intrigued by the connection between the real and implied intimacy. How the viewer understands and interprets intimacy can be tricky especially when the intimacy is queer. In the Stereographic series you are bringing the viewer to the work as voyeur, what are you asking of the viewer? Curious about the answers to the same question about the Through the Lens of Desire work.

KS: I think there has to be some real intimacy behind the relationships in the snapshots that I select to make Through the Lens of Desire work. The people in the original photographs must have cared for each other in some way, if only in a friendly or familial way. The queer rereading is a fiction, but the snapshots that I start with usually contain some actual affection.

The stereographs were made for a specific exhibition titled Dirty Pictures. I wanted to make a series that was voyeuristic, but that was ultimately more about sensuality and intimacy rather than about overt sexuality. I wanted the viewer to feel like they were seeing a private moment they shouldn’t be seeing. I also wanted there to be some subtle tension there, as the illusion of depth really puts the viewer in the scene. Through the Lens of Desire asks the viewer to see the world, and specifically the past, the way I do. There is a lot of projection in that series, which is acknowledged by the circular frame and the series title. The circle can reference a lens, a scope, or a peephole. It is about projecting my view onto photographs from the past and also about seeing what could be hidden in plain sight. The crop also renders the figures anonymous, so the project becomes a work of fiction. I'm not suggesting that the actual people pictured were gay or lesbian, but trying to create an alternative narrative for a for a group of people who would likely not have been photographed in an open and loving way at the time.

HG: One of the powerful things about Through The Lens of Desire is the ability for the images to work alone and also the power of organizing them together in a grid. Each image stands on it’s own as subtle and tender while combined or grouped they act as a normalizing (not sure if that is the right word) force for queerness. Would you agree?

KS: I do agree. The work I make surrounding queer issues is often seeking normalization, which isn’t the aim of every queer artist. I try to create images that are relatable to a broad audience, not just an LGBTQ audience. The series is about the search for love and intimacy, which I think is a pretty universal concept that can speak to different types of relationships.

HG: Thank you for sharing your work with us.