Q&A: Paolo Morales

By Rafael Soldi | Published May 12, 2016

Paolo Morales is a photographer. Exhibitions include the Detroit Center for Contemporary Photography, Kings Highway Library, Pingyao International Photography Festival, Philadelphia Photo Arts Center, and ClampArt, among others. Residencies include Skowhegan School of Painting & Sculpture. He received a BFA from The Art Institute of Boston at Lesley University and an MFA in Photography from Rhode Island School of Design. He currently teaches in the Department of Visual Arts at The Potomac School.

Rafael Soldi: John Szarkowski famously said that all photographers are either a mirror or a window—which one are you?

Paolo Morales: I like to think of my pictures as one-way mirrors. On one side, the photographs reflect back aspects of my own life, and on the other side is the viewer who hopefully sees the pictures as windows onto world.

RS: Tell me about your most recent body of work, These Days I Feel Like a Snail Without a Shell, which was the result of your MFA at Rhode Island School of Design.

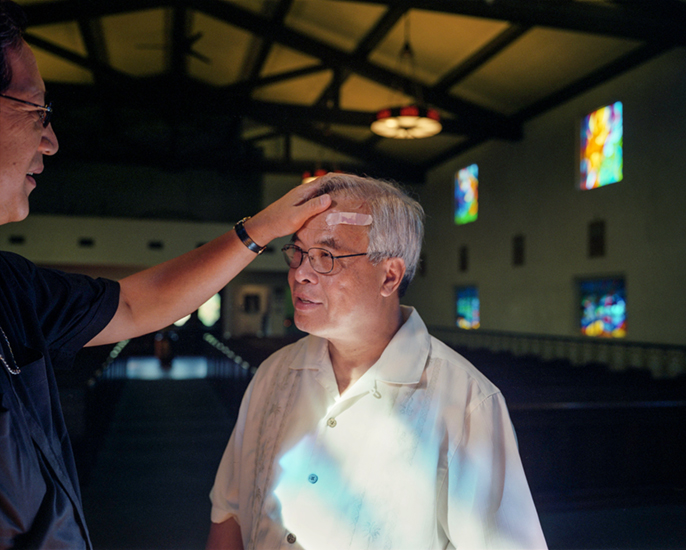

PM: These Days I Feel Like a Snail Without a Shell is a series of documentary-style photographs that show people in states of emotional dislocation and isolation despite being physically close to others. There is a repetition of reaching hands in this work that hopefully creates a visual coherence within the sequence of pictures. I’m interested in the gesture of people reaching out because I see them as attempts to connect to others despite a feeling of isolation. This desire or longing to connect is what motivates the pictures and is also what I like to think the people in the pictures are feeling.

I qualify the work as documentary-style because many of the pictures take on the language of documentary photography but my aim is create something more emotional and ambiguous rather than illustrating a story with my pictures. Also, the term documentary-style suggests pictures that fit under the umbrella of “straight photography.” In other words, pictures that can be understood, felt, and decoded based on the visual information contained in the frame.

During the summer between my first and second year of graduate school I was traveling a lot to make new work. I remember looking for something to read so I picked up a Murakami book titled South of the Border, West of the Sun. I hadn’t read any of his books previously and the title stood out to me. The novel follows a middle-aged man with a family and successful career named Hajime as he goes through feelings of longing and nostalgia for his past. In one scene, Hajime is talking to a woman named Izumi, one of his love interests, and she discloses to him, These days I feel like a snail without a shell. Shortly after I finished the book, I remember telling someone about this sentence. As I thought about it more, I realized it would be an appropriate title because it articulates the feelings of instability and dislocation that I want to project on to the pictures. I also liked it as a title because it could refer to my role as an unnamed and unrevealed character in the work. The sentence is in the present tense (“these days”) and refers to an “I,” which I interpret to refer to myself (the photographer) as a character. The character is vulnerable and is in search of a feeling of safety. This photographer-as-character, then, moves through the world without a shell while remaining in search of one.

RS: I've followed your work for a long time and there have always been a number of running threads that connect your images. One of the things that stands out to me is that your work has always felt journalistic at a glance, but a closer look reveals a strong sense of tableaux—people like Jeff Wall and Paul Graham come to mind. Is your intention to blur this line between reality and a constructed image? How does your image-making process inform this way of working?

PM: Thank you for the noticing that! I think the feeling of the journalism or documentary is partly caused by how few of the people in the pictures gaze back at the camera. Wall and Graham are both good references to respond to. After hearing about Wall so often in college I look at his pictures and can’t help but remember that they’re set-up. His work is often discussed in direct comparison to the work he is referencing. In a way, part of the content of the work is the fact that they’re set-up. With Graham’s pictures, I look at it and don’t necessarily think about whether or not they’re staged. In A Shimmer of Possibility I imagine Graham driving around the United States and snapping photographs and later sequencing it. In Does Yellow Run Forever? I imagine something similar—taking pictures of his girlfriend, rainbows, and pawnshops whenever he comes across a scene. I feel more of an affinity to Graham’s pictures because of how rigorous the sequence is. I would like to think I apply a similar, yet looser structure, to These Days I Feel Like a Snail Without a Shell and Remains of the Day.

But, to answer the last two parts of the question—yes. The photographs I am trying to produce necessitate the blur between reality and constructed images. When photographing, I try to meet people and attempt to insert myself into situations to make pictures. For example, when I was in school, I often went back to revisit subjects in an effort to build a photographic relationship. Ultimately, I aspire to make pictures that suggest and imply my own longings, feelings, and desires. The people in the pictures are undeniably important to me and in many ways they become actors in the photographic fiction I am trying to build. And so this is a long way of saying that the reality I come across sometimes fits in with what I am trying to project, but, more often than not, I will see people do something and ask them to repeat it for the purpose of producing a picture. Other times, when I’ve gained a certain amount of trust with the subject, I will have a list of ideas for pictures and together we will choreograph a picture. I think the pictures have a blurred feeling of reality and construction because that is how I happen to work. I don’t feel the need to only construct images or to only capture something as it occurs. I suppose that is what makes me anxious when looking at Wall’s pictures. For a while, I thought I had to produce work and define my pictures within strict parameters like he does. But after grad school and meeting other photographers, I’ve found that ambiguity is just as interesting, and for the time being, allows for more possibilities in picture making.

RS: Your images predominantly feature people of color, is this intentional? How does your own identity play into your work, if at all? Do you ever think actively about this in making your work?

PM: I don’t believe my identity as an Asian-American male plays a direct role in this work. Some of my family members occur multiple times as does another family who I photographed regularly while in Providence, but I don’t think the work is about them in a socio-economic or racial way. Diversity is important because you can point to it in the pictures, but I like to think of the content of the work is more emotional. To me, the pictures aren’t about diversity or my identity. They’re more about physical and emotional distance, isolation, longing, and desire to reach out to connect. My aspiration is for those feelings to transcend the topics of diversity, race, and economics in the pictures.

When I first got to grad school I remember telling one of my teachers that I wanted to be invisible in my work. I quickly learned that what makes pictures exciting to make and talk about is the quest to make photographs that state an opinion. So in a way, I still want to be invisible in the work, but only in an effort to make the work opaque. In other words, I want to make pictures that make the viewer uncertain of the race, ethnicity, citizenship, or gender of the photographer. And so in that way diversity is really important.

RS: You've incorporated self portraiture into your work from very early on in a unique way. If one doesn't know you, they might not even pick up your presence in the frame. We see your arms, hands, back of your head and even your shadow or obstructed interaction with others. Can you elaborate on these choices?

PM: This is a great segue from the previous question. In college, I made a lot of self-portraits. It often felt limiting because everything needed to be constructed. I didn’t feel any potential for serendipity. Later, I started to incorporate more of myself into the pictures. This goes back to the desire for invisibility in the work. I never appear as a direct representation. The photographer-as-character certainly exists but is never fully described. I like that I or someone else could point to my physical presence (a shadow, a blurred hand) but if someone didn’t see it I would be OK with that, too.

In a pragmatic way, I incorporate myself because it is a way to get work done. Basically, I am an available subject for the pictures. I think about Lee Friedlander’s obsessive self-portraits when making oblique references to myself in the pictures. I do it partly to get work done and partly to fulfill certain narcissistic tendencies.

The presence of my hand is visual evidence of my desire to reach toward another person. I like to include parts of myself because it points to distance in the pictures with others in the frame.

RS: Do you know Nikki S. Lee's body of work Parts?

I am familiar with that work. I looked at it a few times in college. I’m interested in the various roles she plays and how gesture and touch change from picture to picture. But on some level, I can’t get past the basic premise that the images are quite literally parts of a picture. The position of the images in the book exaggerates the crop and I understand it complicates the work formally but I don’t need or want to know that the images are portions of other, larger images.

Lee’s work fleshes out the idea of the photographer-as-character. At this moment, I don’t aspire to make an entire body of work of self-portraits, but I do see her work as something that shows what is possible with self-portraiture, especially from someone who is a minority, a woman, and isn’t Cindy Sherman.

RS: In The Remains of the Day we see a lot of hands. I've noticed hands and arms have been present in your work since very early on. Tell me more about this.

PM: These pictures were a result of a residency I attended in the summer of 2015. The work is sequenced to include a number of pictures of palms. I don’t remember why this came up, but at the residency I suddenly became fascinated with palm reading because of the expectation that palm lines somehow map out a life. So that summer I started to photograph people’s palms in a serial way and imagine them being shown as a grid. I think they also work well within the sequence of this particular project to break up the sequence among the other pictures I made. The fascinating thing about all the people I met in the town surrounding the residency is that they were all hopeful for the future. They frequently talked to me about the future and what they were looking forward to. I believe the palm pictures are representative of that hope and being open to something unknown coming into their hands.

I’m not fully certain why hands are so interesting to me. But I know its one of the ways to reach out, touch, and also communicate with others. It is a powerful part of the body and I am fascinated with what I as a photographer can learn and discover by making more pictures of hands and palms.

RS: What are you up to now?

PM: Recently I’ve been making self-portrait videos where I do things like get fingerprinted or go on a seesaw. I continue to make new pictures and am also printing a lot of work from the past year to sequence in book form at a residency this summer.

All images © Paolo Morales