Q&A: Sara Bennett

By Jess T. Dugan | October 4, 2018

Sara Bennett has been a public defender specializing in battered women and the wrongly convicted, and she is the author of The Case Against Homework. Her photo essay, Spirit on the Inside: Reflections on Doing Time with Judith Clark, was selected for the 2014 INFOCUS Juried Exhibition of Self-Published Books at the Phoenix Art Museum. Her first Life After Life in Prison exhibit examines the lives of four women as they returned to society after spending decades in prison and was featured in, among others, the New York Times, PBS New Hour/Art Beat, and the Marshall Project. The Bedroom Project is the second in the Life After Life in Prison series. It has been featured at The FENCE 2018, Photoville 2018, the 10th International Organ Vida Photography Festival, the 2018 Indian Photography Festival, PDN’s Photo of the Day, among others. Bennett is a Top 50 finalist in the 2018 Critical Mass competition.

Jess T. Dugan: Hello Sara! Thank you so much for taking the time to speak with me today. Let’s start at the beginning: how did you discover photography, and what inspired you to pursue a life and career as a photographer?

Sara Bennett: When I was a teenager, I worked in a darkroom, but I didn’t pick up my camera again until I was in my late fifties. I was studying to be a yoga teacher, and for my final project I decided to photograph yoga practitioners over the age of 50. My husband, photographer Joseph O. Holmes, set up a camera and lights for me and that work ended up being featured in Parade Magazine online.

Tracy six months after her release. East Harlem, NY (2014)

“This is my third home in six months. I was at Providence House [a halfway house]. But my time was up after four months and I ended up at a three-quarter house. It was horrible. Then the uncle of my grand-children, not related to me, took me in.”

JTD: You worked previously as a public defender specializing in battered women and the wrongly convicted. Did this experience lead you to photography? How do you feel that your advocacy work influences your photography, and vice versa?

SB: For many years, I was the pro bono attorney for Judith Clark, who was serving a 75-year-to-life sentence for her role as a getaway driver in a famous New York Case—the Brinks robbery of 1981. I was trying to get the governor to grant her clemency, something rarely granted, and I had to show that she was extraordinary and worthy of the governor’s mercy. One day, shortly after I completed the yoga photos, it popped into my head that I could photograph women who had been incarcerated with her and have them speak about her influence on their lives. I borrowed my husband’s camera and took 15 portraits, which I self-published as a book, Spirit on the Inside: Reflections on Doing Time With Judith Clark. I sent it to the governor, state legislators, and pretty much anyone I could think of. Not only was Judy granted clemency, but the book was selected for the 2014 INFOCUS Juried Exhibition of Self-Published Books at the Phoenix Art Museum.

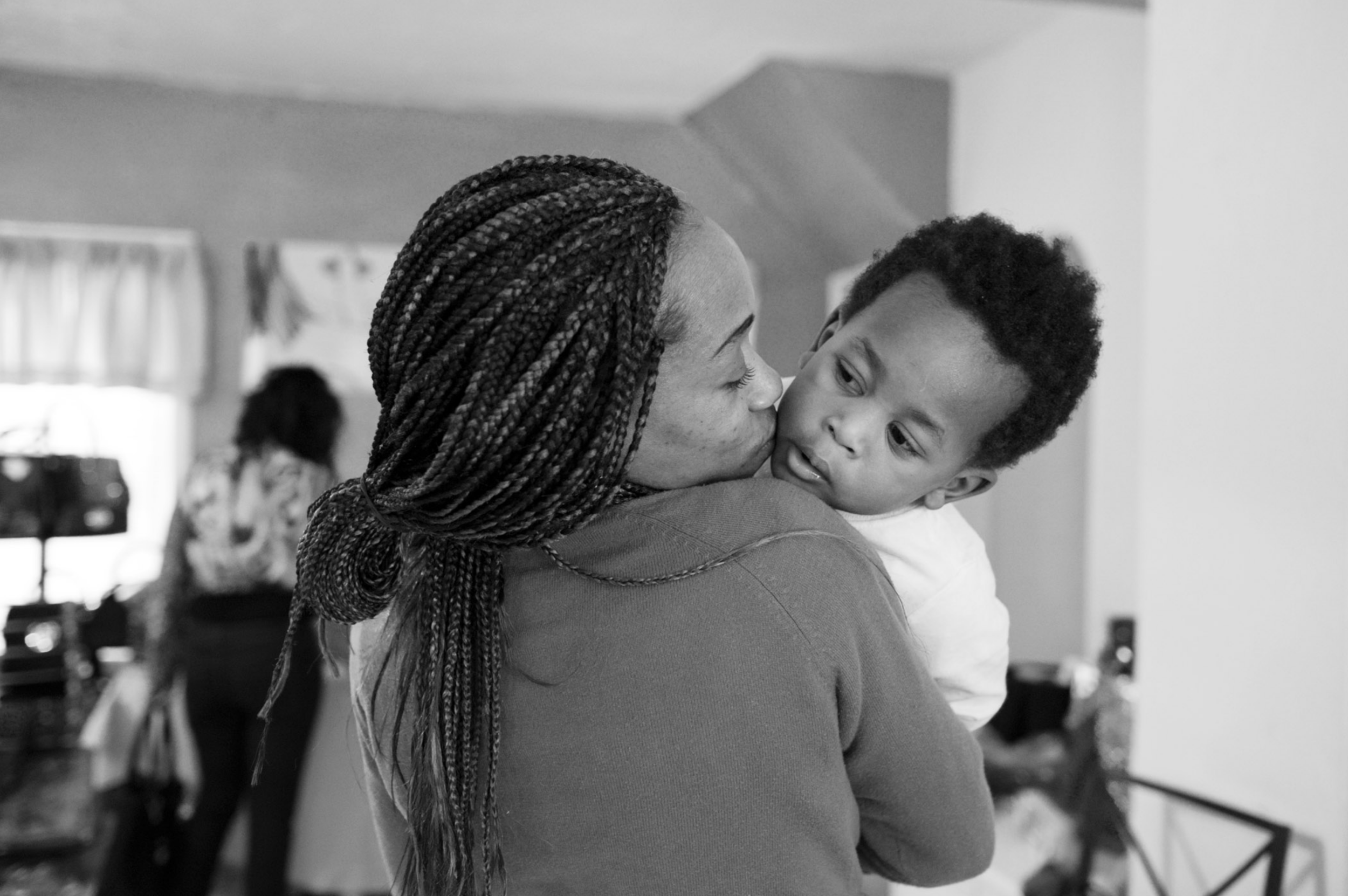

Evelyn, who served 17 years, with the son of her domestic partner. Long Island City, NY (2014)

“I met my partner when I’d only been home for a few days. She has three kids and me not having kids, I became close to the kids and that was an extra.”

JTD: Tell me about your project Life After Life in Prison. What was your motivation for beginning this body of work?

SB: It was the reaction to Spirit on the Inside—viewers were surprised that the formerly incarcerated women were just regular women—which sparked my second project, Life After Life in Prison. I followed four women — Tracy, Evelyn, Carol, and Keila — as they returned to society after serving anywhere from 17 to 35 years in New York State’s maximum security prison for women.

Carol in her bedroom. Long Island City, NY (2015)

“I don’t know why they finally gave me parole on my sixth try. I had a good record. Maybe it’s because I’d had two heart attacks and I was expensive. You can’t make up for 35 years. The world is different; I’m different. I wasn’t going to do a ‘catch-up.’ How do you catch up for 35 years?”

JTD: I imagine that gaining the trust of your subjects is a significant part of your work. How did you select your subjects? Were they people you knew previously before making photographs together, or did you seek them out specifically for this project? What was your process for working with them?

SB: I had talked to Judy about my idea for Life After Life in Prison, and she told me about Keila, who had been home from prison for about two weeks after serving 20 years. The first time I met Keila, she was on her way to a meeting of formerly incarcerated women, and I tagged along with my camera. There, I told all the women about my project, and they all wanted to be included. A lot of the women at that meeting already knew of me, either through my work on Judy’s behalf or because I had represented some of their friends as a Legal Aid lawyer.

I started spending time with about 9 women, which was way too many. It became clear pretty quickly which ones were eager to let me into their lives in a meaningful way, and that’s how I ultimately settled on Tracy, Evelyn, Carol and Keila.

Keila living in her cousin’s home after her release from prison. Long Island, New York (2014)

“My dad bought me this softball glove when I joined the prison team. He died while I was in there. Two officers transported me to the funeral home. I was in cuffs for twenty hours. He was the man I loved the most in this whole world. It just went all wrong. They made it worse.”

JTD: You photographed these four women for several years. How do you feel the passage of time affected this project?

SB: Before the first year and a half was up, I had my first exhibition and the work was featured in a variety of media outlets. Multiple exhibitions followed. So, I thought of the work as pretty much finished, although I continue to photograph them on occasion. But the longer the women are home, the more their lives become mundane, in a good way, and the less there is to capture.

JTD: How did your relationship with your subjects change over this period of time?

SB: Over the course of more than 15 exhibitions and multiple panel discussions with the four, I got to know them better, I became more involved in their day-to-day struggles, and I began mentoring them more heavily.

CLAUDE, 45, in transitional housing five months after her release. Corona, NY (2017)

Sentence: 25 years to life

Served: 25 years

Released: February 2017

“When I step into my room, I feel like I’m stepping into another world. I spent 25 years isolated. I really isolated myself. My room in the prison was my safe haven. There was no negative energy. No one came in unless the officers were doing a room search. It was my cocoon, my womb, where I feel the safest. It’s the same thing here. It’s my space. Everything in the room belongs to me, so I have a claim. I have things I was not allowed. I have glass bottles, perfume, shower gel, my mom’s ashes. My mom’s picture in a picture frame with glass. I shed the day the minute I cross over the threshold. I am home.”

JTD: Tell me about The Bedroom Project. Did this develop naturally out of Life After Life in Prison?

SB: I had taken bedroom portraits of all 9 women I originally followed for Life After Life in Prison, thinking that it might make a separate project. I didn’t end up using most of those images in The Bedroom Project, though, because, as a new photographer, my portraits weren’t yet good enough. And later, when I was deep into The Bedroom Project, I couldn’t reshoot them because many of those women had moved away.

JTD: How do the two projects overlap and/or differ?

SB: The Bedroom Project is in many ways a continuation of Life After Life in Prison, because my subjects are again all women, they all had life sentences (meaning that they had a sentence of “x” years to life), and my intention in both projects is to humanize the women.

For both projects, I want to give the viewer a glimpse into all kinds of issues—what it feels like to live in a cell, educational and employment opportunities inside and outside of prison, the difficulties in getting parole and being on parole, finding housing, and feelings of remorse, regret, and forgiveness.

SHARON, 57, back in supportive housing seven years after her release. Corona, NY (2017)

Sentence: 20 years to life

Served: 20 years

Released: May 2010

“My body tells me, I was in prison, but my mind tells me that I never spent a day there. I have this sense of freedom and a strong sense of feeling liberated. I am so in touch with my womanhood, of being a mom and a grandmother, a friend and a partner, a spirtitual sister. I’m in touch with all that . . . my room is a place of peace and a sanctuary to come home to every day. I love turning the key in my door.”

JTD: On your website, you have a section called “mitigation packages,” and you have created portfolios to “present to DAs, judges, and/or governors, in an effort to show the humanity of the people whose fates are being decided.” What role do you think photography can play in advocacy work?

SB: I hope my photography sparks empathy and leads the viewer to think about people who are ordinarily unseen. I believe that if judges, prosecutors and legislators could see lifers as real individuals, they would rethink the policies that lock them away forever. For mitigation work, I think a photograph or two can be enough to make sentencing judges see the person in front of them as a real person—a person with the potential for rehabilitation, a person with children who might become motherless or fatherless, a person who is more than their worst act, etc. In the criminal system, judges and prosecutors generally see the defendant only as a criminal. A photograph is a quick way to show the defendant’s humanity.

NIKI, 55, in transitional housing four months after her release. Corona, NY (2017)

Sentence: 15 years to life

Served: 23 years

Released: March 2017

“I’m happy to have my own space, my own room. I’d love my own apartment, a steady job, but for now I want my Bachelor’s Degree. I got 2 Associates’ Degrees that I earned in prison. The first one was through Marymount College in Bedford, and the 2nd was through Bard College in Bayview. Bedford is the only women’s prison that offers a Bachelor’s program. I remember when I was transferred to Albion, I couldn’t even attend college because you had to be under 25 years old to be in the program and at the time I was over 40. The age-cap was eventually raised to 35. I still didn’t meet the mark. However, when I transferred to Bayview, I attended Bard College there, but could only earn a 2nd Associates. Now Bard has an Associates Program in Taconic. That said, I just enrolled at York College and by December 2018, I will have earned a Bachelor’s Degree. Hopefully, one day, it will l all come together, I’ll have my education, my own place, I’ll be off parole, and I can travel.”

JTD: How do you personally combine art and activism?

SB: As a lawyer, I represented individuals, but as a photographer, I am able to raise awareness about all people in prison. The Bedroom Project was exhibited on The FENCE 2018 and at Photoville 2018, both big public venues. Passersby seemed sympathetic, drawn in, and incredulous at the amount of time that the women had spent in prison. At The FENCE I eavesdropped on many conversations and at Photoville I was able to engage with thousands of visitors. No matter what happened in the women’s pasts, today they are hard-working, loving, resilient, optimistic people. Viewers seem to understand that the women (and others just like them, whether inside or outside prison) have earned second chances. Now it’s up to those who make policy to also understand that and put an end to decades of escalating sentences and parole denials.