Q&A: Sonja Thomsen

By Rafael Soldi | October 6, 2016

Sonja Thomsen (b. 1978) is a Milwaukee-based artist whose multifaceted practice combines photography, sculpture, interactive installation and site-specific public art to create spaces reflective of our own perceptions. Since earning an MFA in photography at the San Francisco Art Institute (2004), she has exhibited with Higher Pictures, DePaul Art Museum, Center for Photography at Woodstock, the Reykjavik Museum of Photography, New Mexico Museum of Art, Madison Museum of Contemporary Art, Gallery f5,6 in Munich among others. Thomsen's work resides in the collections of the Milwaukee Art Museum, Reykjavík Museum of Photography and the Museum of Contemporary Photography. Accolades include the Mary L. Nohl Fellowship for Individual Artists, Milwaukee Arts Board New Work Commission, Digital Artist in Residence at Columbia College Chicago and a Hermitage Artist Fellowship. Sonja Thomsen is a member of the international photography collective Piece of Cake and co-director of The Pitch Project.

Thomsen is a Lecturer at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago.

Rafael Soldi: The evolution of your work has been exciting to watch. You have for a long time resided in a ‘photographic’ world—you are part of photo-based collectives, teach photography, and are connected to the photographic community. But your work is more spatial than it is photographic, a direction you started to explore early on with Lacuna, which expanded how your images occupied space. But in viewing and experiencing your work, sculptors, installation, and light artist seem to better fit into the narrative of your practice. Photography is one of those mediums and communities that has managed to remain segregated from most of the art world, with its very own set of rules, groups, festivals, publications, and language—this is not new, it spans nearly 175 years. Conversely, most other visual art mediums seem to coexist in closer harmony. What is your connection to photography, and how does it continue to influence your work, if at all? How are you navigating the transition into a new visual language? Has this divide been a challenge to your practice?

Sonja Thomsen: One of my favorite Buckminster Fuller quotes is, “We experience becoming.” My practice embraces my own time based knowing and respects the flow of working in the studio.

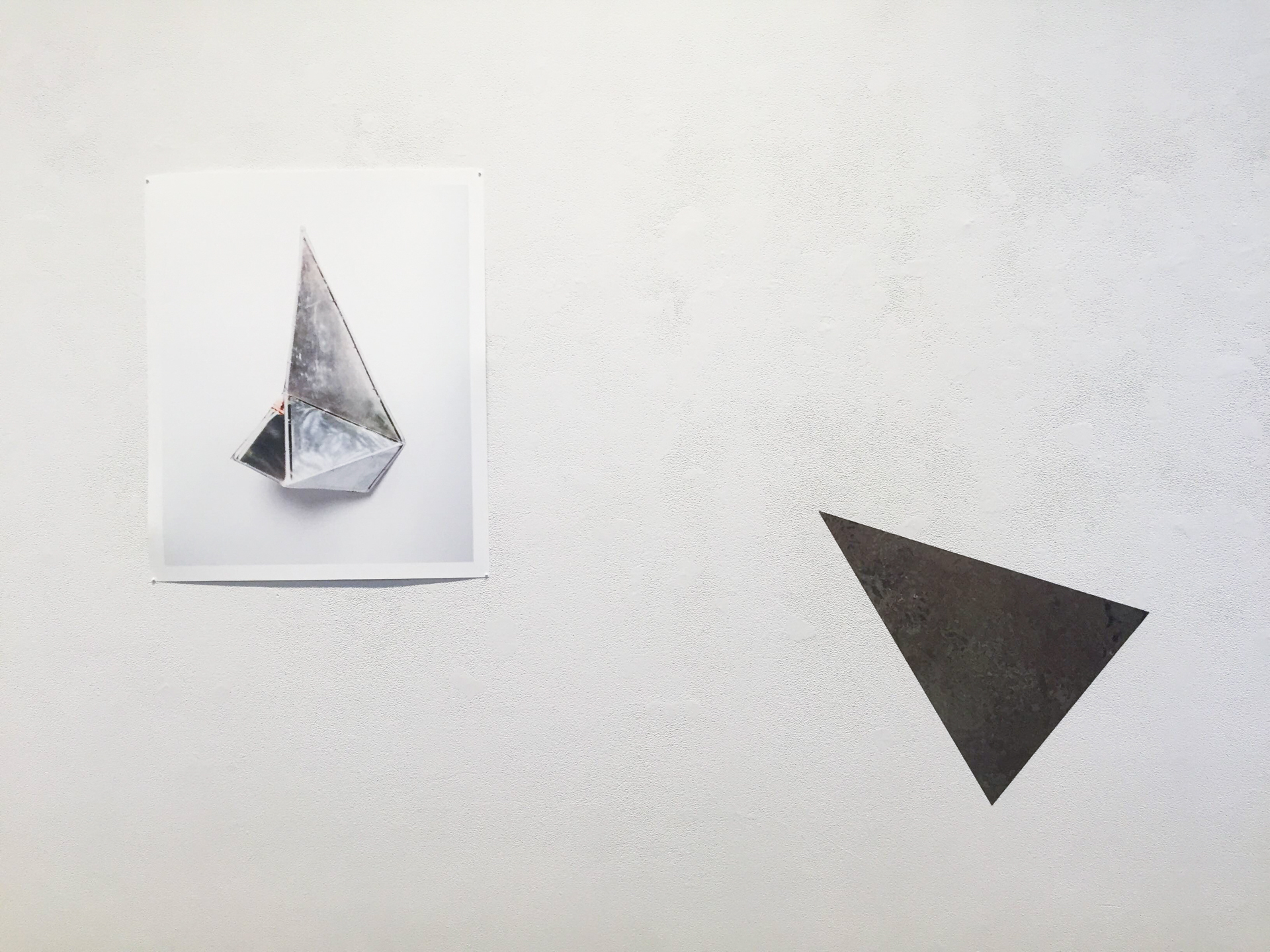

The last five years have been really fruitful for my work and research. One of my first sculptural pieces, “trace of possibility,” launched a newfound freedom to embrace abstraction, obsess about light, and make space for my fascination with science (and now math.) I sketch with my iPhone and scanner a lot. I work in a cyclical way, usually starting with an image, then constructing, exploring materials, printing, constructing, reshooting. I think about most everything as an experiment and then the site specificity drives decisions on form.

When constructing an installation, I think about a photographic way of seeing; locating yourself in relation to the world, framing space, using light and time as materials to work with. I am interested in creating spaces that highlight the inaccessible, mediating perceptions of margins. As we get closer comprehension moves further away.

This kind of work does not resolve itself in a box of prints that some of the photographic community still clings to. Thankfully, I have been fortunate to surround myself with people that are invested in the evolving definitions of photography and embrace artistic risk taking.

RS: How do you explore your feminist ideals through your work, and how does it fit into a history that has long been told through the lens of Western male artists?

ST: That is a great question and something that I am starting to consciously pay attention to. Much of my current research focuses on the women of the light and space movement and the scale of their work and materials. The reflective glass microspheres of Mary Corse, and the site specificity of Maria Nordman are major influences in my work. At this moment I am interested in the practice and construction of community of photographers Lucia Moholy and Sarah Charlesworth.

When I took a history of photography course in 2001 we were using Beamont Newhall’s 1949 edition of The History of Photography from 1839 – present. Can you believe that? Newhall only mentions thirteen women in the entire history of photography. There are many groups excluded, which to me is what really embodies the Western male authority. Thankfully we have a few better texts to use today.

I recall Linda Connor asking me if I was a feminist landscape photographer in graduate school. I owned the title, but it felt more about a personal connection rather than overtly political at the time. But of course it is political. Since then I have had more experience with our patriarchy, which makes her teaching come alive.

RS: Tell me more about the materials you have chosen to work with. I’m intrigued by the fact that the formal elements of your sculptural work are almost entirely dependent on light, and the way the form takes shape to the human eye versus the camera apparatus. It’s a bit of a subliminal tip of the hat to your photography background.

ST: Thanks for that. I continue to be fascinated by how an installation is experienced with a person's own eyes versus with the mediation of the camera. It's exciting when people start making pictures within the installation and are surprised with what they see through the lens.

Light is my material. I try to work with media that is flexible and accessible on my scale. I have been experimenting with other media that animate the light: camera, steel, metallic vinyl, mirror, polycarbonate, prism, silver gelatin paper, glass microspheres (nod to Mary Corse), and more recently shade cloth.

The show that I am opening next week uses this fantastic aluminum netting. I am just getting to know this material, but I love that it is shade cloth that refracts light. It works kind of like a two-way mirror does, seeing the surface and seeing through.

RS: In our conversation you referred to the sculptural form you’ve been working with for the last few years as a female form. (I’m reminded of Louise Bourgeois, who was known to refer to her totem-like forms as female forms, and many of her sculptures were gendered and given personhood in that way). You said She is aggressive, She is gendered—and we talked about her imminent demise, you’re asking yourself how to resolve her, and even talked about the idea of ‘killing’ her to put an end note on that form. Talk to me more about this, the idea of gendering work, and how you envision her end.

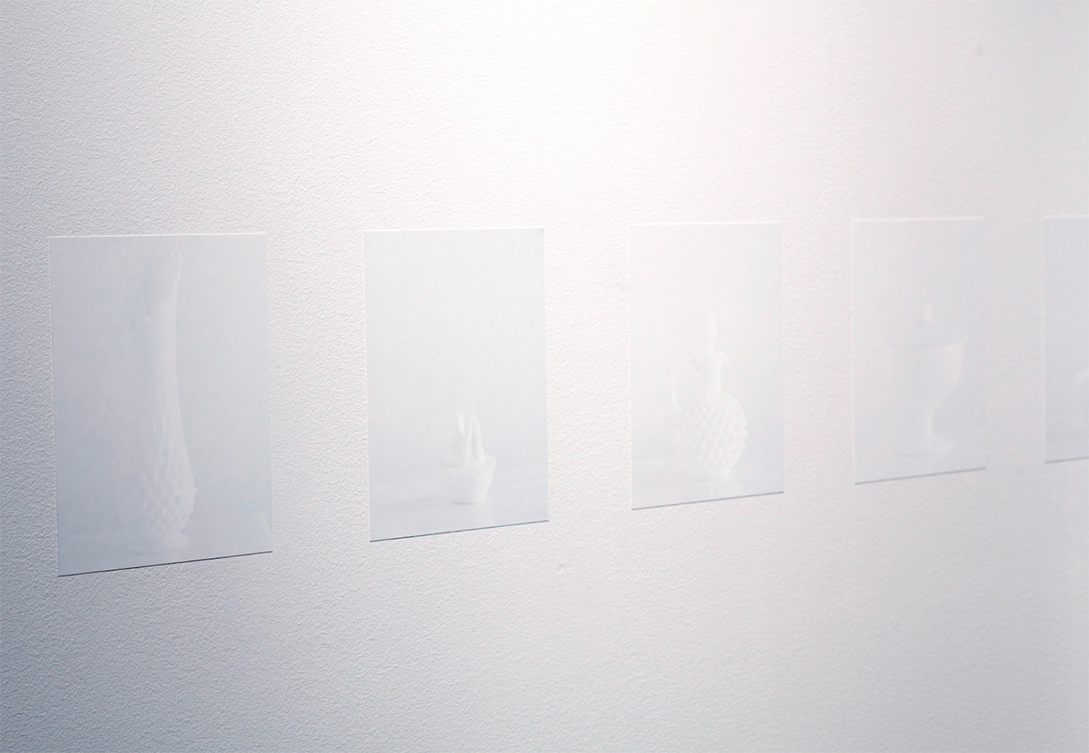

ST: I was a new mother at the time of conceiving of the sculptural work “trace of possibility.” I was thinking a lot about the metaphor of woman as vessel and working on a series of photographs of a collection of my great grandmother’s milk glass. I wanted to connect to a generational history while simultaneously thinking about the obscuring of self or the challenge to not feel invisible as a mother. The installation of the milk glass images, white on white adhered directly to the wall, literally disappeared. In contrast the sculpture owned its space. She embodies dualities. She is cavernous and mountainous, an abstract landscape. She is a light modulator. She is a potential photograph, a mirror without the memory.

I have learned a lot from this piece. She has generated a lot of new work and lead me down diverse lines of research. Last spring, I installed her in a new orientation at the John Michael Kohler Art Center in Sheboygan WI. She was up in the air and rolled on one side – it was great to see her in a new way. This has only emboldened my desire to install her in a landscape. I think about her in the southwest, in a similar landscape as Walter De Maria’s lighting field. She would feel so small here; the sun and elements would wear on her. I think about her in Iceland—it was after a winter trip to Reykavik with four hours of twilight a day—where the idea originated. I want to film her in the landscape and allow the land, weather and time to make their mark on her.

RS: Lets talk about riffing and improvising. The recent years of your practice have consisted of an organic riffing on form, material, and ideas—one growing naturally from the other. In a way I find it interesting that your work is female-gendered and it’s regenerative, since women are the ones who birth new life into the world—it seems appropriate that your sculptural form would offspring. But back to this organic riffing/improv idea. As an artist myself, I often feel the weight and expectation to work in a structured project form is heavy… sometimes you just want to make things and they’re not always as conceptually concrete as we wish them to be. You actually said to me that the sublime is grounded in fear, and there is no other way to explore the sublime than to do it in an esoteric, abstract way—and that’s a little scary. What are your thoughts and experience with working in this format?

ST: I think we were talking about wonder being grounded in delight and the sublime in fear.

I intensely trained in ballet in my adolescence – I had an incredible jazz teacher that would ask us stiff bun heads to improvise one by one across the floor. The lesson is to trust your technique and be present in your body, to have fun in the movement. I feared this part of class every week. I fought the request (what a waste of time) and when I finally allowed myself to really dance I freaked myself out – with judgement, doubt and regret. I try not to allow this self-sabotage to happen in my studio today allowing me to create from a place of curiosity, discovery, and delight.

RS: Has teaching in any way informed your practice?

ST: Students’ vulnerability and openness always leaves me grounded in the importance of the work. I have been thinking recently about a lecture by artist Ann Hamilton, for two reasons. First, she talks comprehensively about embodied knowledge in her practice. I value the knowledge manifested in the body as well as the mind. This has me recalling Moholy Nagy’s Vision in Motion, “to learn to see and feel in relationship.” This simultaneous comprehension is something I seek to embrace. Second, Hamilton frames her making, her teaching, and her mothering as one united practice. I am modeling that way of thinking in my own practice – to see things as a part of a collective whole rather than at odds with one another. My time in the studio, with my students, or with my children, all feed my research on wonder and perception.

RS: What’s next for you?

ST: I am opening a show “in the space of elsewhere" at Mt. Mary University’s Marion Art Gallery here in Milwaukee. I am working on an exhibition in LA and two site specific museum installations for 2017. As artists we are open to the possibilities of an unscripted future. Right now it’s grant and job season, so who knows what’s next!

© all images Sonja Thomsen