Q&A: Zulfikar Ali Bhutto

By Rafael Soldi | October 14, 2021

Zulfikar Ali Bhutto (b. Damascus, 1990) is a visual artist, performer and curator. Bhutto's work resurrects complex histories in the South Asian, South West Asian and North African region. In the process he unpacks the intersections of queerness, Islam, speculative fiction, futurity and environmental degrdeation through a multi-media practice rooted in printmaking, textile work and performance. Bhutto has performed, shown work and curated exhibitions globally, as well as spoken extensively on the intersections of faith, radical thought and futurity at Columbia University, UC Berkeley, NYU, Stanford and the Indus Valley School of Art and Architecture. Bhutto is currently based in Karachi, Pakistan and received an MFA from the San Francisco Art Institute in 2016.

This is a transcription of a video conversation.

Rafael Soldi: Hi Zulfi, nice to see you. Where are you right now?

Zulfikar Ali Bhutto: Hi Rafael. I am in Karachi, Pakistan, in my home. We just had a pretty epic rainy season, the whole city flooded recently. It's been raining non stop for 48 hours, but thankfully the rain was very light this time.

RS: And are you and are you in your family home?

ZAB: I'm in my family home, but I'm not with family. My mother lives in Lebanon. You know, I'm half Lebanese. I take care of my brother and the family home here in Pakistan.

RS: And until recently you were in San Francisco for graduate school, was returning to Pakistan always the plan?

ZAB: Yes. I always knew I would return, but that priority shifted a bit this last year. I always knew there were so many things I could do in Pakistan. You feel more useful in a country like this, especially with a foreign degree and with access and resources. It feels more accessible, you feel more impactful. I stuck around in San Francisco for a little while after school and eventually I felt less safe about going back to Pakistan. I started doing drag and more openly explicit queer performance. I sort of went into this semi self-imposed exile. I think I never saw myself as an immigrant in the US. I always saw myself as a visitor or more aptly, perhaps a guest. And although the US doesn't necessarily treat all their guests the same way, I thought, well, I am your guest. I didn't feel like this was a place that was for me, even though there were moments where I thought, OK, this is probably the best place I can be right now doing the work that I'm doing. But in the end home is not something that you can just convince yourself you're in. For me home was very physical, home was very land-based. Because I grew up half-Lebanese, half-Pakistani—the Pakistani side of me being Sindhi, Sindhi people are very much about the Earth. And that idea is rooted in you from a very young age, everyone here shares this idea in our province, that it's our motherland. And even for Lebanese people, their resilience is because of their love of that land. It's very rooted in a certain place. So feeling unrooted becomes an especially disorienting experience because you can't help but constantly go back to your roots. Right? Even at the expense of being misunderstood in the place that you have been unrooted from.

RS: Well and that's a great background to understand your current work, titled Tomorrow We Inherit the Earth, which is this umbrella project that I'd love to unpack with you. But a couple of things that you mentioned really hint at the core of this work. One of the main characters in in this work is an alter ego that you've created, Faluda Islam. She's this sort of queer heroine, a guerrilla fighter in this alternate universe where she's pushing back against this Western idealism. So I liked hearing you talk about feeling like a guest or visitor in the U.S.—in the West. Almost as if you were a spy, or gathering information from the inside, in the context of this fantastical world that you're creating. And we were also talking about your family—you mention in your statement that a lot of this work is influenced by your father.

ZAB: Yeah, yeah, for sure. I love this idea of being a spy in the US; I don't think that's necessarily untrue. Of course, I'm not an agent working for an authority, but in a creative sense, yes. I think it was definitely a way of gathering information about that side of the world but it wasn't just "enemy territory," I made so many friends there. So this idea of solidarity beyond borders; we see historical legacies with the Black Panthers for example.The Panthers and the Palestinian movement, and various other US grassroots movements that especially happened in the sixties and seventies. That legacy, that history is my inspiration for this whole series. How do we speak to the ghosts of this particular past that had so much potential but had such strong enemies that it just didn't survive? I think internally we often condemn the leaders of these movements, but the reality is that there were strong forces working to divide us. So people get scared, and people get tired, and people get hungry. So then we just don't continue.

This project has several layers, and one of them is a film series called ABJD that kind of completes this umbrella project. It's very much a dialog with ghosts of the past. Each film uses my alter ego character, Faluda Islam, who is a sort of freedom fighter in this other world. I often refer to it as the future, as a way to create a story, right? I do like to think of it as the future, but sometimes the future feels so close. It's easier to create a story in the future because the future is inherently unknowable. But really I prefer to say another world, or another possibility, or another reality, or another kind of framework of thinking.

RS: I can't help but think of Jose Esteban Muñoz, whose insights into queer futurity feel so aligned with this work. He famously writes that "Queerness is not yet here. Queerness is an ideality." And he argues that queerness is a "horizon of being" that can be glimpsed in gestures and worlds beyond the present. And I think that's true beyond queerness. Many movements don't have the luxury to look to the past or the present, often relying on the foundation of a future that we can't see or know. That comes through for me in looking at your work, and in the way in which you're constructing these worlds that are unknowable.

ZAB: Yes, for sure! In the early stages of this project Muñoz was a major inspiration, and his writing was a major inspiration in understanding queerness not just as an LGBTQ umbrella term. Queerness is technically an idealized humanity that we have not reached yet. Queerness is inherently futuristic because we are not there yet. So that idea for me was very powerful. He's been a major force in my life.

RS: What else informs your work?

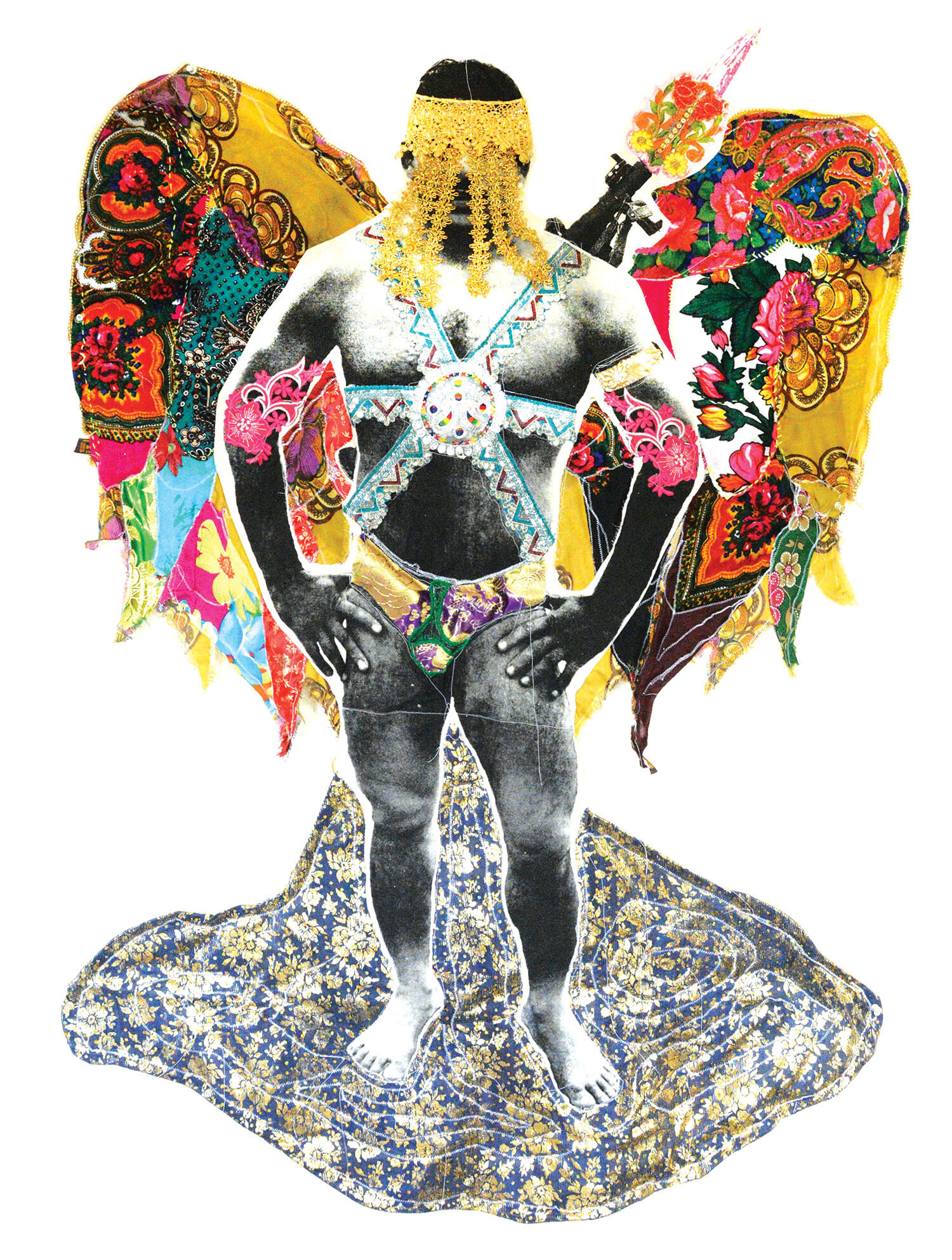

ZAB: Popular iconography within the South Asian and Arab contexts. Shia Muslim iconography in particular holds the real futurist potential. Because it ultimately projects narratives of martyrdom and heroism and valor, as well as being eternal, meaning we will meet our martyrs again. Because our martyrs are not just fighting for us, they're fighting for a much bigger, wider cosmic ideal. So a lot of my tapestry and textile pieces reflect that.

RS: And it appears you often take this approach: embracing traditions, folk tales, and ancient cultural or religious ideas as a starting point but adding a new layer of complexity to create a parallel track or universe.

ZAB: Yes, exactly. Parallel tracks is a really great way to describe it. I often think of how things could have been. And that's why even a lot of artists who are not necessarily always future-specific, use the future because it's hopeful.

RS: And it doesn't exist yet, you get to create it.

ZAB: Exactly. Totally. But I feel like with the climate crisis and the unashamed amassing of wealth and inequality, the corporate greed. The future is here, right? The future is very much in our face and it's very, very scary. So futurism started to feel a lot more like escapism for me. So this idea of parallel tracking is so appealing. Is a lot more connected to the everyday realities of today. And I think that happened for me when I moved back to Pakistan. I come from a family of privilege, so I'm not trying to say that I was faced with the day-to-day realities of the everyday Pakistani, but I was certainly faced with realities that I didn't face in the West. In the U.S. one can end up in this constant capitalist cycle of self fulfillment, and when I moved back to Pakistan I was forced to think of many people who depended on me, people who I depend on in order to make my mark here. This is especially true as a queer person just to be comfortable here. Even with access to resources, the future cn feel more precarious here—both the present and the future feel urgent.

RS: Well, that urgency is informed by the problematic nature of how the past is represented. By how we come to understand it through archives and histories that are inherently subjective, written by those in power through an imperialist lens. So it's really difficult sometimes to rely on the past or on histories because we don't always know them to be truthful or unbiased. And I think that's another place where futurity becomes really important as a way to reject the power imbalance that governs how histories are told.

ZAB: I completely agree. History is all made up. I would say all mainstream narratives are made up. And like you said, all we have is our archives to piece things together and to sort of make our own histories. But then the future becomes a way of reworking that history. So if history is already made up, why not really go for it, you know, and make up your own stories.

RS: Let's talk about some of the formal elements in your work. I'm really curious to hear about some of the footage in your films, which appears to be borrowed or sampled. And maybe let's go back earlier to your tapestries where you're using imagery of wrestlers. Where are you pulling these images from? And since these tapestries represent the earlier part of the project, maybe expand on that trajectory too of how the whole project built up over time. I think there are several questions in there!

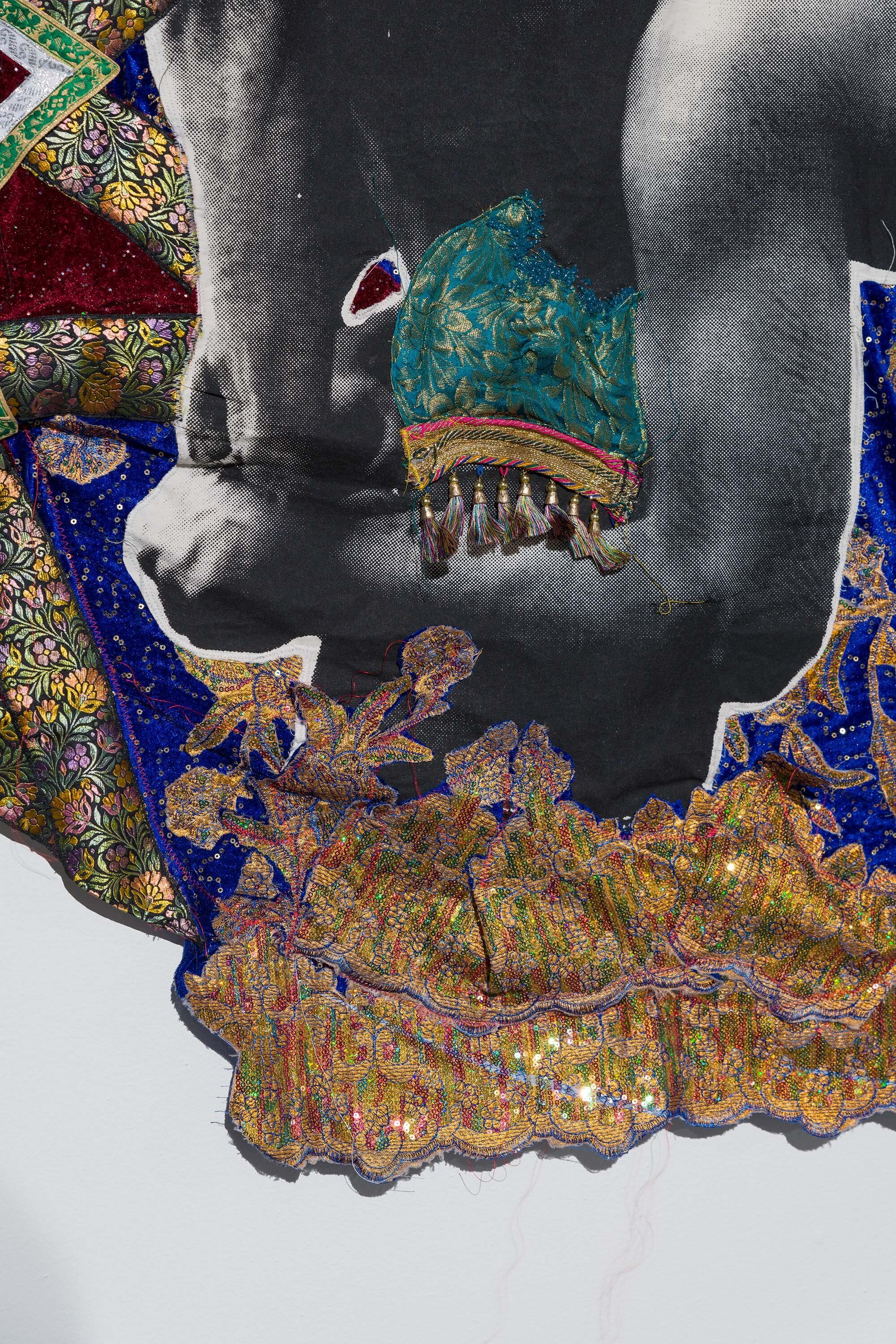

ZAB: Yes! I'll tackle the source imagery question first. So the wrestlers actually are images I took myself. I'm very into archives, and a lot of my films have archival footage, which I am now delving into many legalities of as I continue my practice. But as for how we ended up at this point. I love photography. I love painting. I love pretty things. I love film editing. I love making stories. And I love collage. So a lot of my early struggles as a young artist were about figuring out what really properly obsessed me, you know? Early on photography was a big love of mine, and I loved taking photos around Pakistan because the country is on the precipice of modernization, radicalization, and colonization, so it felt urgent to document this place as it changed quickly. Pakistan has always remained a little bit safe because the global powers need us. They need us to stay where we are. They need us to be a puppet. But it's a very diverse country filled with many people from different faiths—we're two hundred and five million people between the Middle East and India. We have both of these cultures melding together in one country. So I wanted to document that. And then the idea of documenting that felt a little problematic because we're also a very poor country, and it started to feel a bit exploitative. So I started taking photos of staged areas of male performance, and wrestling was one of them. Peacocking in wrestling was a big thing, and people were really excited to have a photographer there. I was in a world of spectacle. Eventually I created the series out of those photos because within South Asian and even Iranian culture the wrestler is used as an archetype of heroism, valor and love as well. So this, for me, felt like a good transfer as a conceptual idea into this re-imagining of what a revolution could look like. You know, in this sort of mystical, magically-realized speculative future, right? The speculative reality. So the wrestler felt very obvious to me as a stand-in for the soldier. Right? In an earlier body of work I had played with stitching, quilting, and embroidering sequins and flowers onto male muscle imagery but I sort of exhausted that material. And at that time, I kept my performance practice separate because it was so drag-oriented. I kept them both as very separate things. So when I started to conceptualize "Tomorrow We Inherit The Earth'' and thinking about revolution in the future and I liked the material of wrestlers photographs that I had made earlier, but there was a lot of maleness and I wanted to bring in a female element, so I revisited the earlier techniques to create these multi-media tapestry works. In the film works you also begin to see this female character come in, Faluda Islam, the drag character who I performed in nightclubs. I brought her into the narrative—her story is that she died in the revolution as a freedom fighter and she has returned as a zombie to tell the story of it.

RS: Well let's talk more about these film works. I was really taken by one titled heaven 58. So this film splices together found footage alongside footage you've created. The archival footage is black and white, and it's quite strange. And we also see you in your male form, and also we see Faluda Islam sort of entering and exiting the frame, almost swaping places with you at times. There is a mirroring, a masculine and a femenine—and you're obviously connected but I don't get the sense that you're in the same room. Maybe you each inhabit your own universe.

ZAB: Yeah, exactly. The the idea of the mystical and Islam is a big part of this project too. So it's not just about revolution and history. I consider myself a practicing Muslim and the world of the Jinn (the world of the unseen creatures that live in parallel worlds along with us) is a mandatory part of Islam as belief. The Koran says, O Jinn and Men. It speaks to both creatures. Islam is almost 1,400 years of lived practice, the ideas within it, of course, evolve depending on what world you live in, depending on where you are. So in this particular film, Faluda Islam is interacting with an older film made by Jean Genet titled Un chant d'amour (Song of Love). Un chant d'amour is about a panopticon prison that houses Algerian revolution fighters. This is actually the assumption that scholars have made, as to what is happening in that film. In his film the guards, riddled with homoerotic undertones, spy on the prisoners inside their cells. So I replaced one of his characters with my character, inside the cell. And so she interacts with the historical archive in this way again, and the prison cell becomes a portal between the world of humans in the world of Jinn. And dreaming is a science in the Muslim world. And so the Jinn comes to this person/prisoner in their dream, and the idea is that potentially this Jinn is them. So yes, this piece is sort of a fever dream, there is a lot of hallucination, a lot of dreaming, a questioning of reality.

RS: There are some very sensual moments, too. There's a guard blowing smoke through what almost looks like a glory hole...

ZAB: We actually had to drill a hole in the wall, fun fact! And there was someone on the other side blowing smoke. But yes, very sensual moments!

RS: And the other thing that stands out to me now, after talking more with you, is that the man on the other side of the wall, the watchman, is a white man. There's a Western world on the other side of that wall attempting to exercise control, but what's going on inside that cell seems to exist beyond that physical world. Imagination is beyond the realm of control.

ZAB: Yes, for sure. And this idea of the constant gaze of the West on our bodies and on our sensuality. The original film definitely points to sensuality as a form of liberation throughout time. The idea that we have always been here and we have always been in revolutions and whatnot. And the prison guard, through his gaze, tries to stop that. And in Pakistan we also have this idea of the evil eye, right? So the evil eye is both the eye that watches and the eye that protects. So once the gaze confronts itself it loses its power.

RS: Have you ever read a book called Before Night Falls by Reinaldo Arenas?

ZAB: No, I have not.

RS: I think you'd find it compelling. Arenas was a queer Cuban writer who was persecuted and jailed by the Cuban dictatorship because of his dissent and his homosexuality. He was an outspoken rebel who managed to escape Cuba after many years of tragic oppression and fantastical adventures in sexual liberation. He sadly perished to AIDS once he immigrated to the U.S. But he has this quote that I love, that I think really speaks to this idea of how powerful beauty, art, dreaming, imagination, and futurity can be.

"A sense of beauty is always dangerous and antagonistic to any dictatorship," he writes, because it implies a realm extending beyond the limits that a dictatorship can impose on human beings. Beauty is a territory that escapes the control of the political police. Being independent and outside of their domain, beauty is so irritating to dictators that they attempt to destroy it whichever way they can. Under a dictatorship, beauty is always a dissident force, because a dictatorship is unaesthetic, grotesque; to a dictator and his agents, the attempt to create beauty is an escapist or reactionary act.”

So the idea of beauty is really scary to people in power, and that's why powerful bodies have always been very wary and very scared of artists, right? Art feels so uncontrollable because it traffics in ideas, because it is rooted in futurity and imagination. Plus, beauty is universally irresistible, it's emotional. You can't trap it.

ZAB: Yeah, totally, totally. The idea that people in power find beauty to be so threatening, and joy to be so threatening. It's a beautiful thing. That is very real. And that's something we're seeing so much now globally, even under democratic governments. We see that a lot here. I mean, Pakistan just passed a law that you can't speak against the army, for example, and the army has a lot to speak for in our country's history. So I think, you know, we see these limits on freedom and expression and everything happening in really awful ways that seem less overt these days.

RS: Zulfi, I've really enjoyed our chat and want to bring us to a close because we're in such different time zones! I know that you're working on the last installments of the films, what is left for you to address in this work? What's next?

ZAB: So I'm in the process of editing the last film. It speaks to the Lebanese civil war and the role of one particular female freedom fighter who is infamous because of her role against the Israeli occupation of southern Lebanon, which didn't end until 2001. My character goes from being Jinn to being a zombie, a confused zombie, a literal living martyr. This idea of liberation and death is so important because of how populations in the in the "global south" have been so hounded by oppression and disappearances and murder and all these things. The destruction of the body is the final voice of protest. I come from a family that values martyrdom. My aunt and my father and my grandfather and my uncle were all killed by the Pakistani state, the very state that I live in. And in some paradoxical way, the country that I love. And as much as I don't believe in nationalism, I can't help but love this country. So this idea of martyrdom is very close to me.

So the next film tackles that, and then the fourth film will be a little bit more out into the solar systems. But then after that I'm ready to move on. Now that I'm in Pakistan and working here, I actually feel my attention drifting to other things. Most importantly, land-based art. I'm from the province of Sindh that experiences heavy, heavy water issues, but also has Pakistan's only surviving population of river dolphins. So I want to go to the dolphins and I want to make art about the river and how fragile this ecosystem is. So merging some of the magical realism of this current project with something more earth-based.

RS: That sounds great, thank you so much Zulfi. I'd also like to note that fittingly, it's Friday night here and it's Saturday morning there, which means you're speaking to me from the future. It feels only right for you to answer my questions from the future.

ZAB: I am speaking to you from the future! Yes. Thank you Rafael for your time, I really enjoyed this conversation.

RS: Me too, thanks Zulfi.